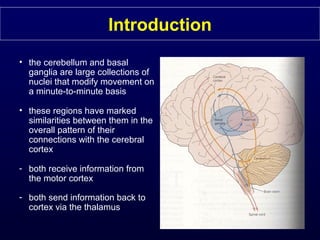

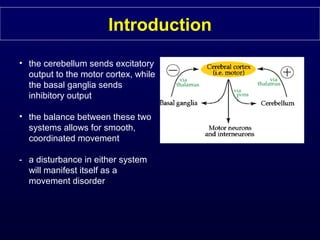

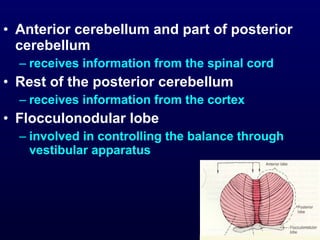

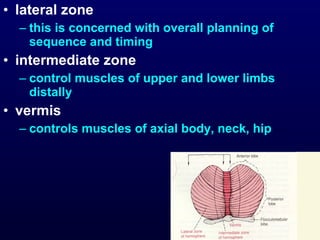

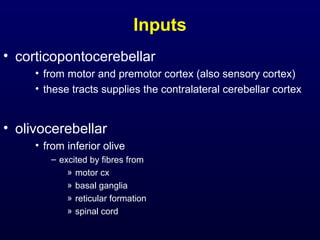

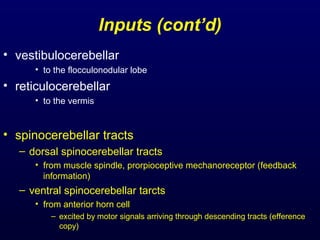

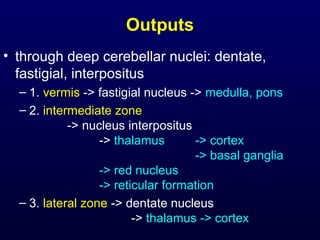

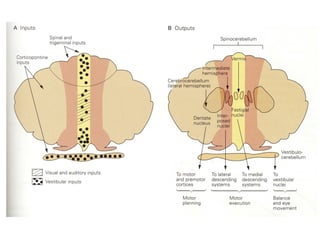

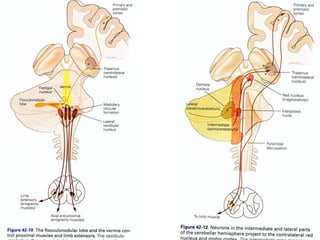

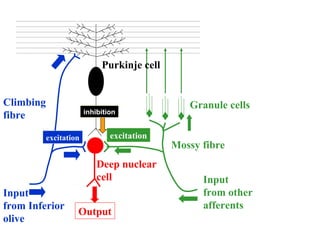

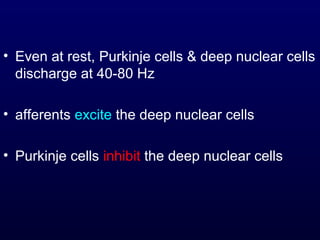

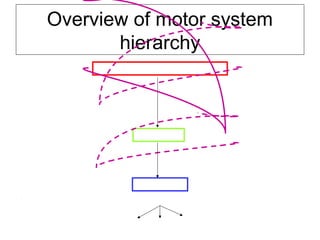

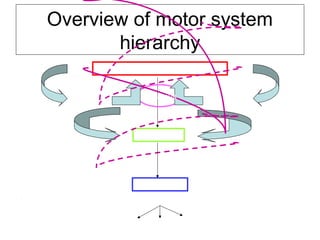

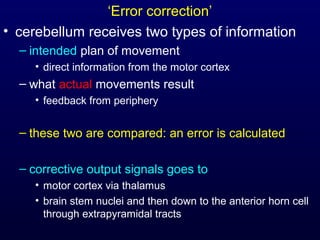

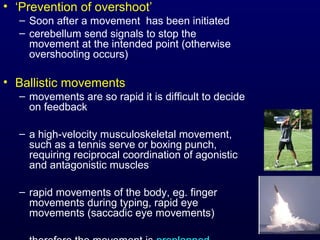

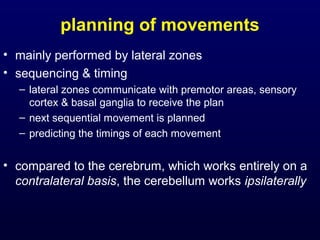

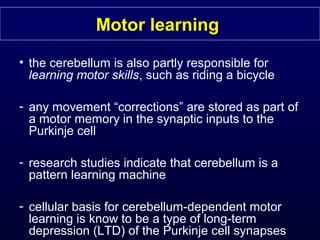

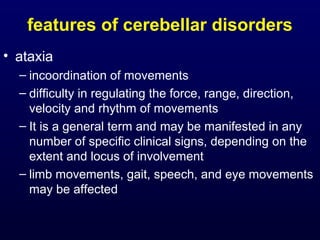

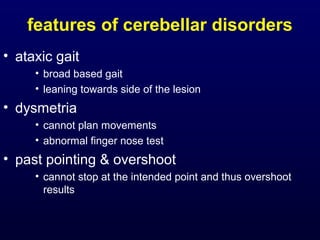

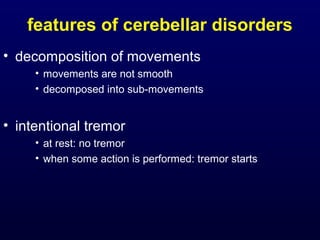

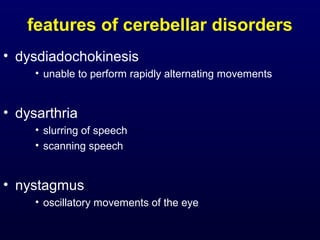

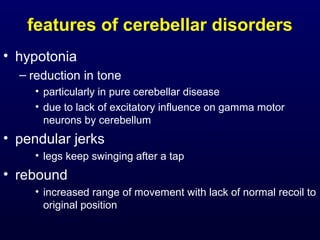

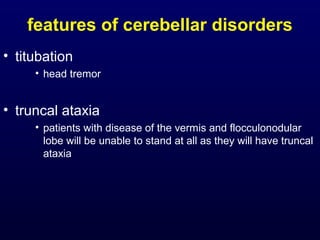

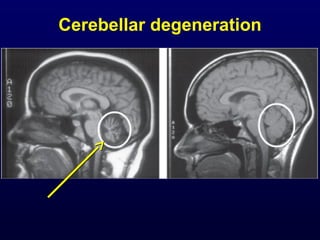

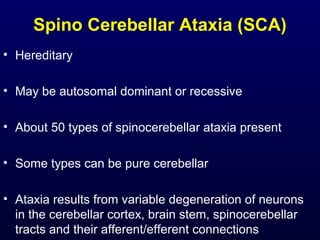

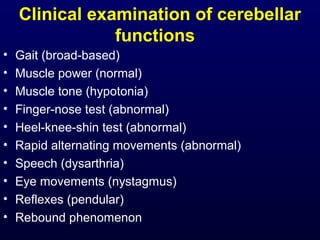

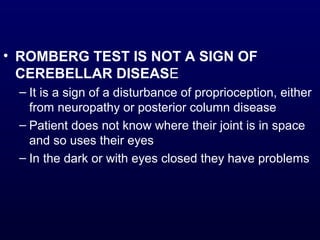

The document discusses the role of the cerebellum in motor coordination. It describes how the cerebellum receives input from motor areas and provides output to modify movements on a minute to minute basis. It is involved in planning, timing, and adjusting movements as well as learning new motor skills. Neurological diseases that impact the cerebellum, like strokes or ataxias, can cause movement disorders characterized by incoordination, gait issues, dysmetria, and intentional tremors.