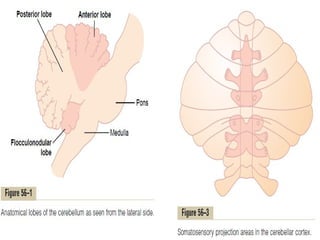

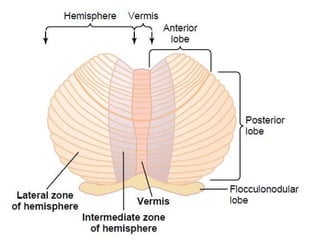

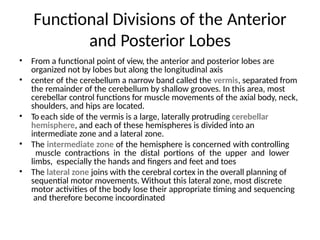

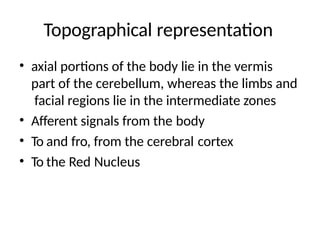

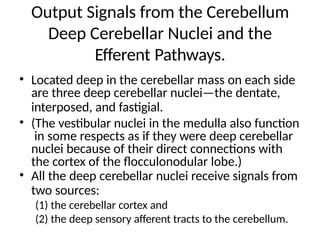

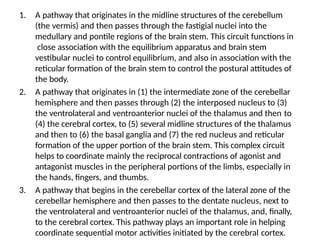

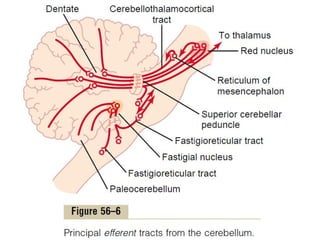

The cerebellum is crucial for coordinating motor activities, ensuring smooth transitions between movements, and controlling muscle contraction intensity based on changes in load. It processes continuous feedback from the body's peripheral sources and the cerebral cortex to correct movements in real-time and assists in planning subsequent actions. Anatomically, it is divided into lobes and functions as a complex network of circuits that facilitate precise motor control across various body parts.