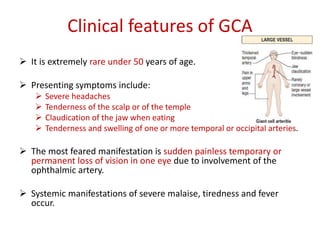

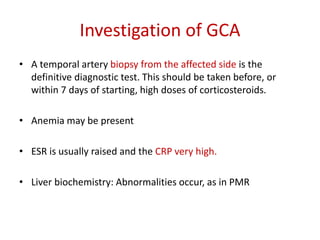

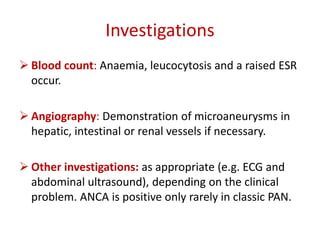

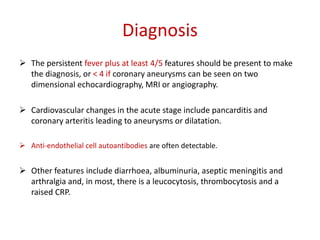

This document defines and describes different types of vasculitis. It begins by defining vasculitis as inflammation of blood vessel walls. The two main ways of classifying vasculitides are by the size of blood vessels involved and the presence or absence of ANCA. Small vessel vasculitis can be ANCA-positive (e.g. Wegener's granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome) or ANCA-negative (e.g. Henoch-Schönlein purpura). Medium vessel vasculitides include polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki's disease. Large vessel vasculitides include giant cell arteritis, Takayasaki's disease, and poly