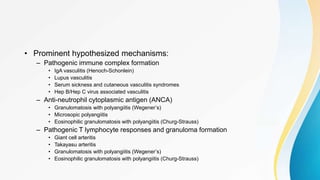

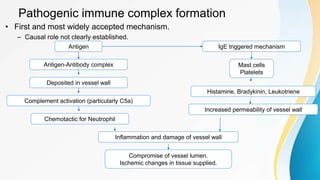

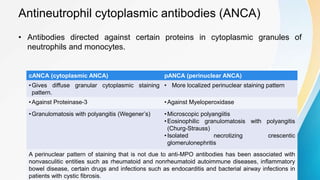

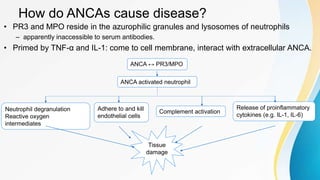

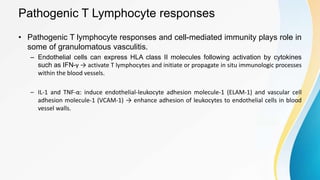

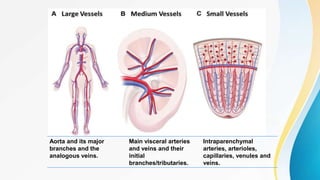

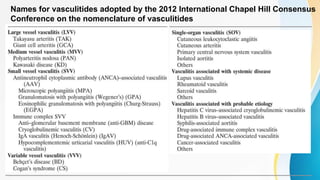

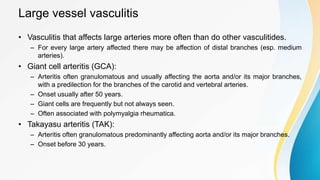

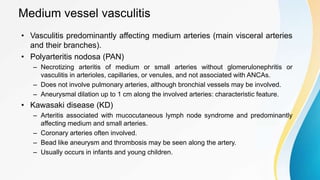

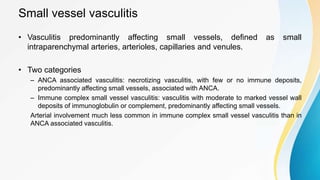

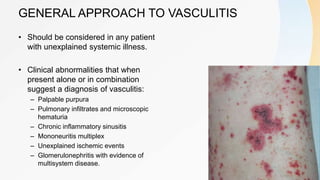

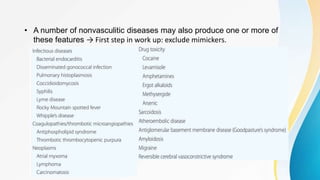

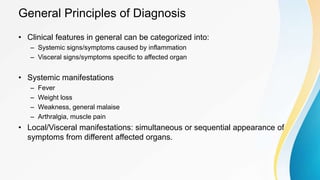

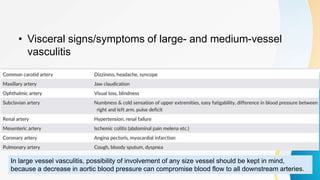

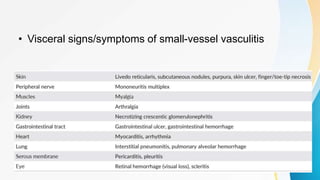

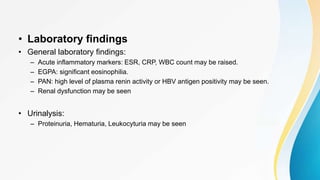

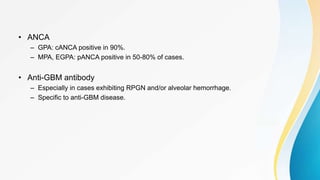

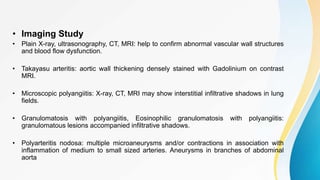

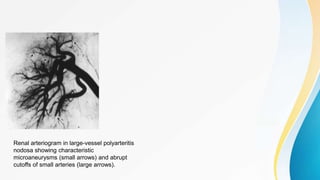

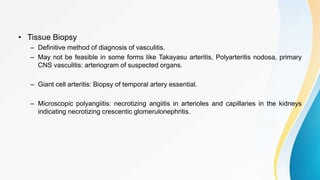

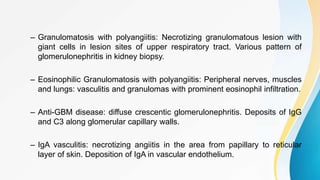

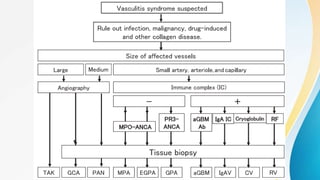

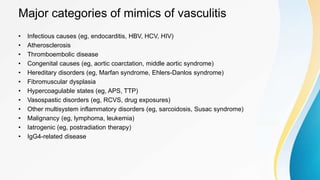

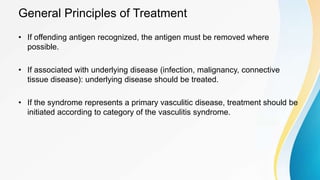

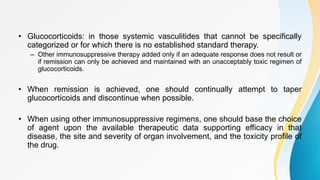

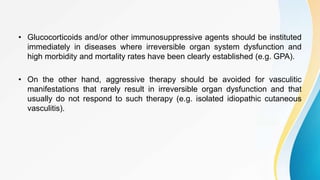

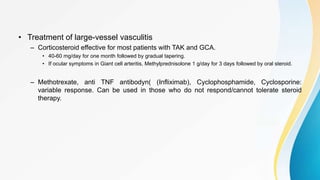

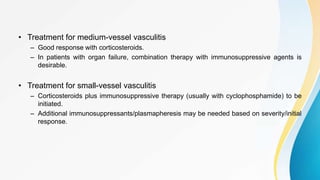

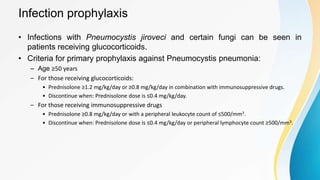

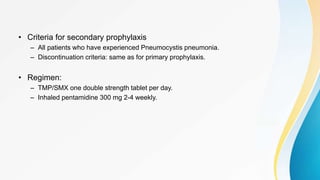

Vasculitis refers to inflammation of blood vessels. This document discusses the pathophysiology, classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of various types of vasculitis. The main types include large vessel vasculitis (e.g. giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis), medium vessel vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease), small vessel vasculitis (ANCA-associated vasculitis like granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and immune complex small vessel vasculitis (e.g. IgA vasculitis, antiglomer