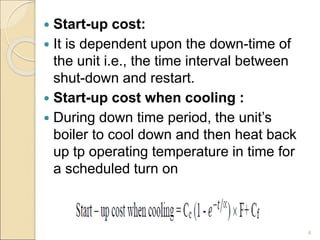

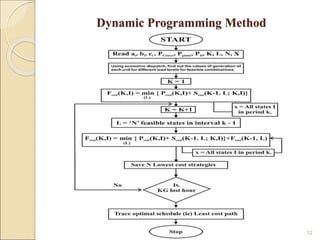

1) Thermal power plants have minimum up and down time constraints due to the time required to bring units online and cool them back down. One hour is typically the smallest time period considered for unit commitment.

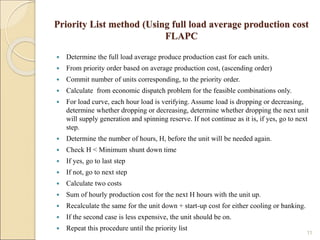

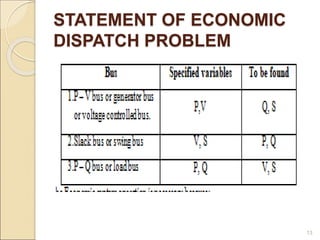

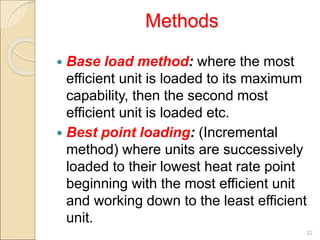

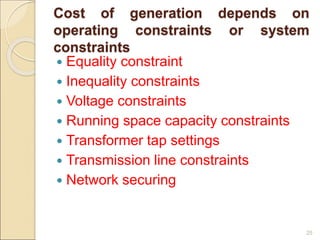

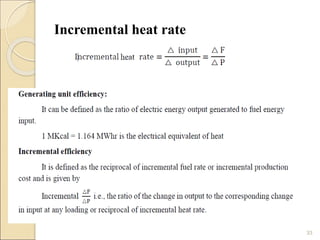

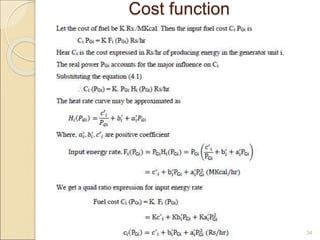

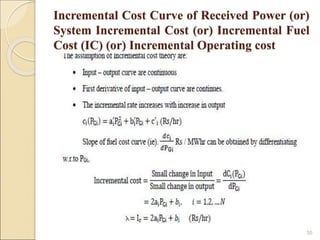

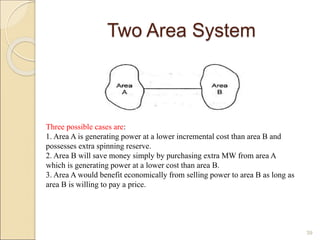

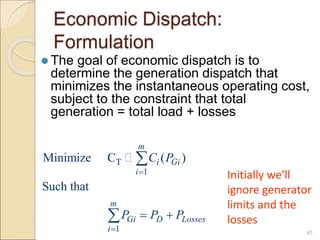

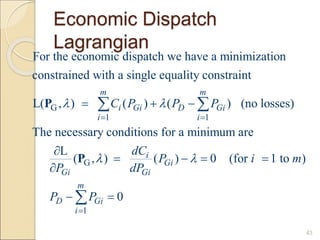

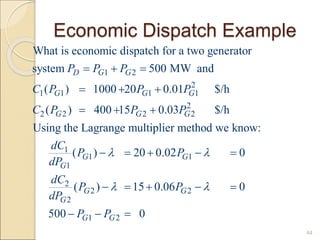

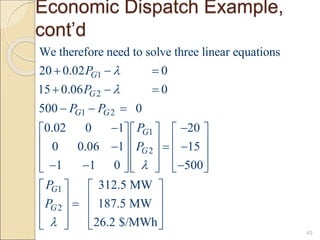

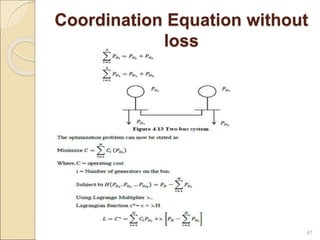

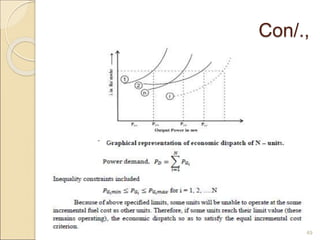

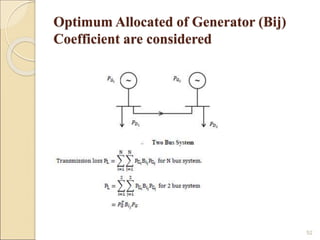

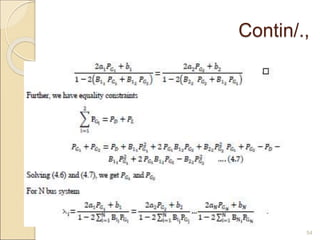

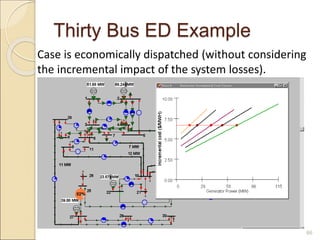

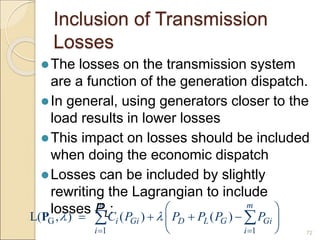

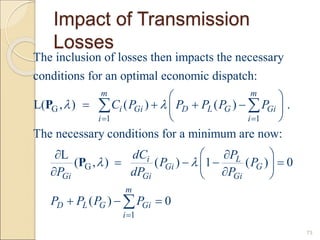

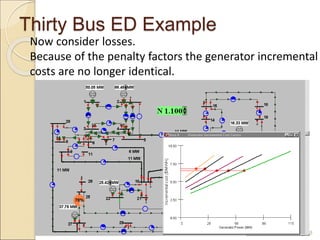

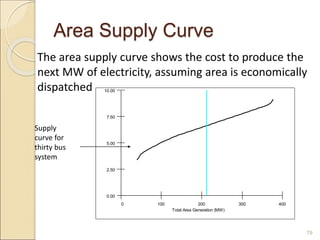

2) Economic dispatch aims to minimize total operating costs given demand and transmission constraints. This is done by allocating generation across available units to equalize their marginal costs.

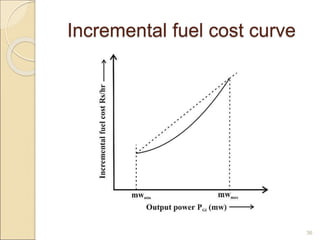

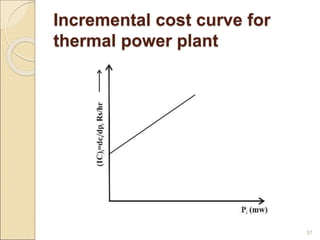

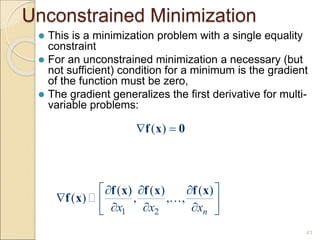

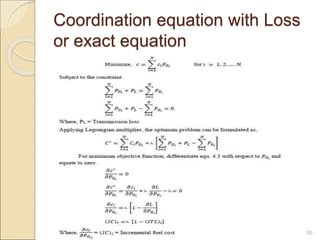

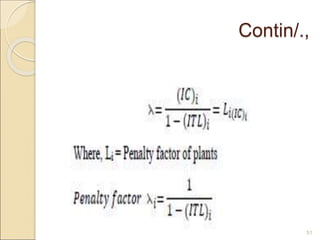

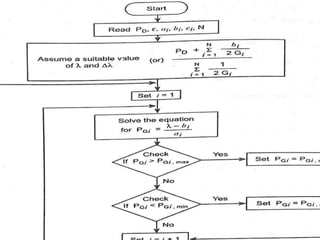

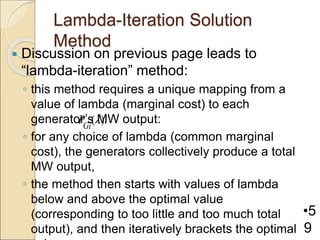

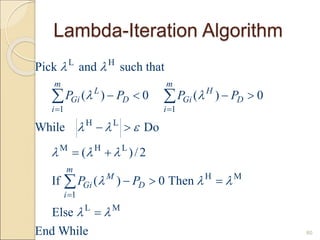

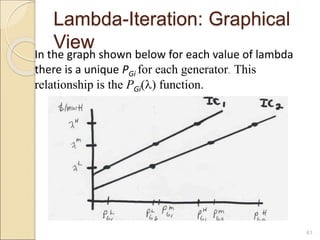

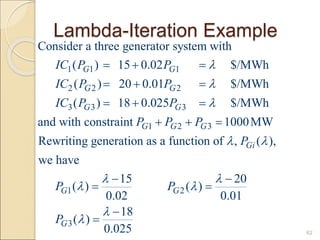

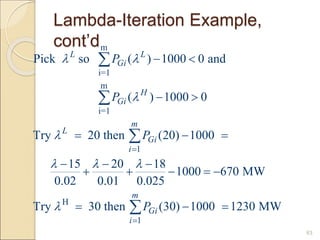

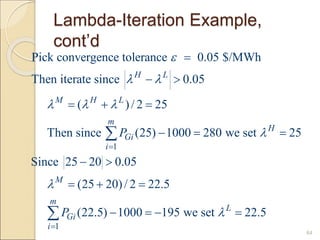

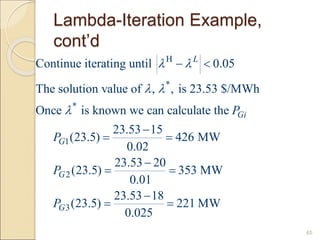

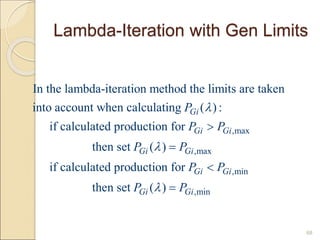

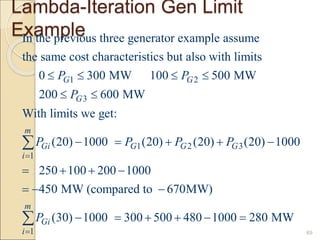

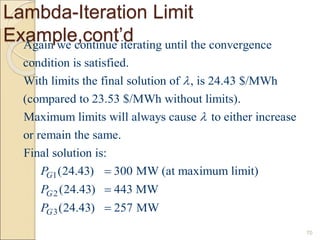

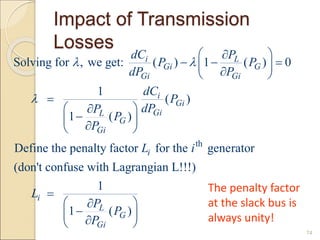

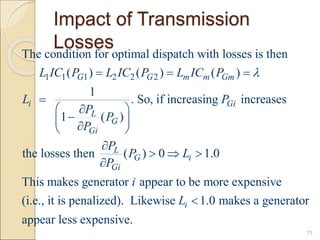

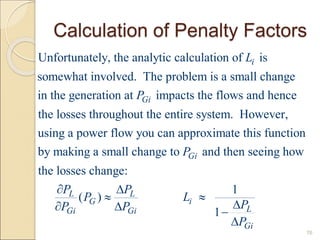

3) The lambda-iteration method solves economic dispatch by iteratively choosing a system marginal cost (lambda) and calculating the corresponding generation dispatch until demand is met with minimum costs. It generalizes to systems with multiple non-linear generator cost functions.