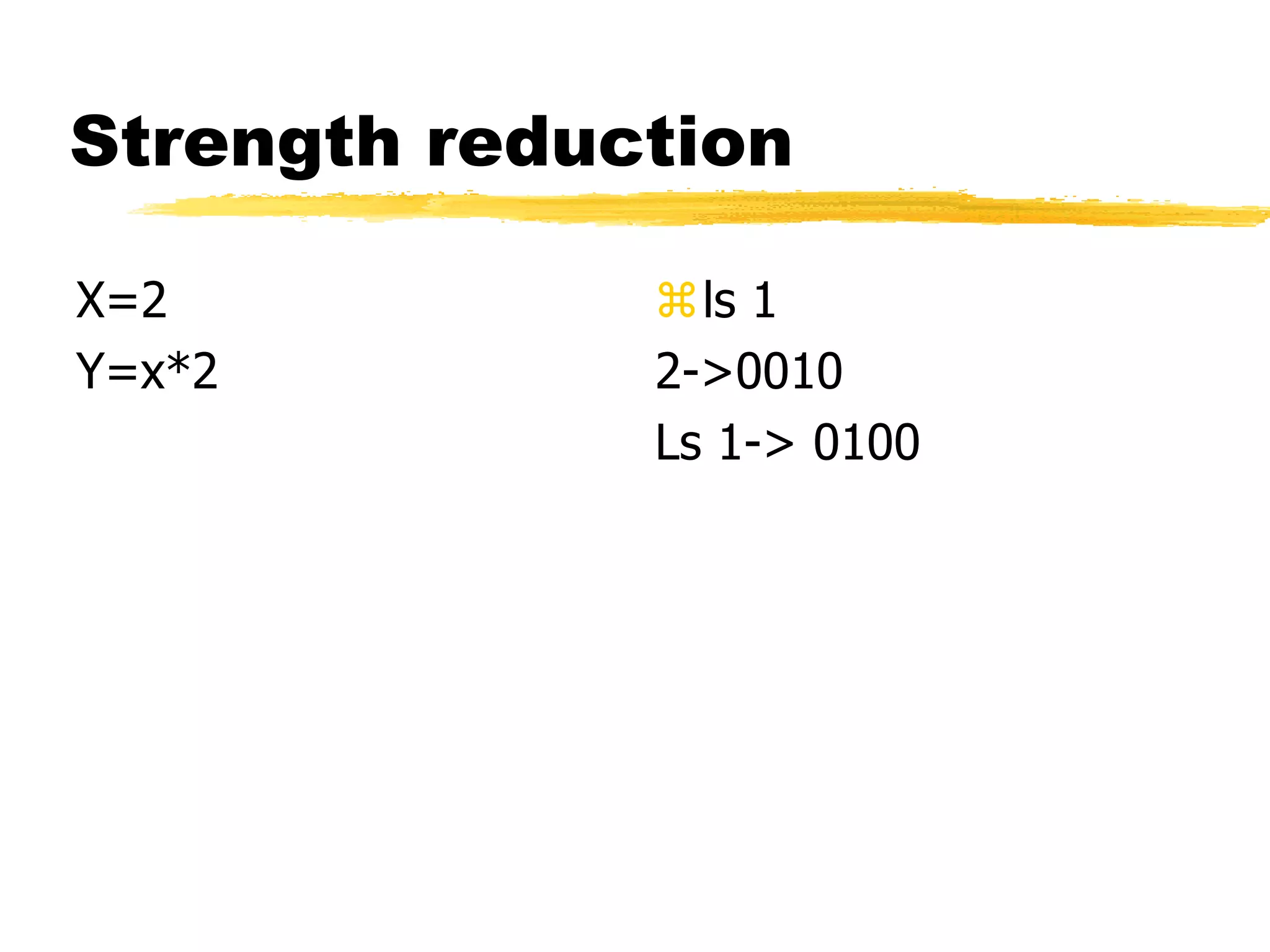

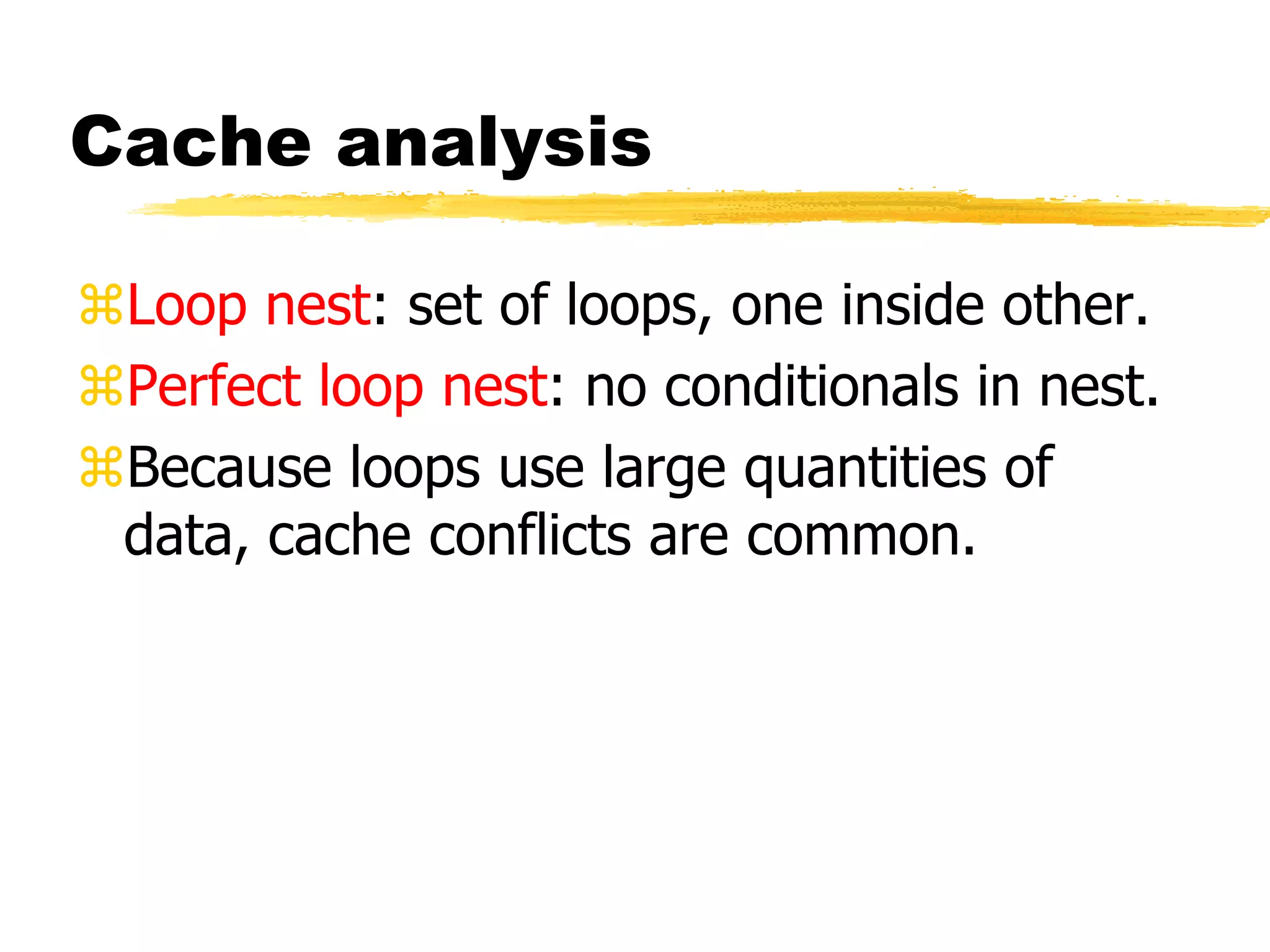

The document discusses program design and analysis, focusing on performance metrics such as execution time, energy consumption, and program size optimization. It emphasizes the importance of measuring program performance through simulation and profiling while presenting various techniques for improving execution speed and managing cache behavior. Additionally, it covers program validation and testing methodologies including black-box and clear-box testing, highlighting the significance of testing execution paths and ensuring functional verification.

![Paths in a loop

for (i=0, f=0; i<N; i++)

f = f + c[i] * x[i];

i=0

f=0

i=N

f = f + c[i] * x[i]

i = i + 1

N

Y](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit3part2-200903161624/75/Unit-3-part2-9-2048.jpg)

![Code motion

BEFORE OPTIMIZATION

for (i=0, f=0; i<N; i++)

{

x=y+z;

a[i]=6*i;

}

AFTER OPTIMIZATION

x=y+z;

for (i=0, f=0; i<N; i++)

{

a[i]=6*I;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit3part2-200903161624/75/Unit-3-part2-18-2048.jpg)

![Induction variable

elimination (nested loop)

BEFORE OPTIMIZATION

for (i=0; i<N; i++)

{

for (j=0; j<M; j++)

{

z[i] [j]= b[i] [j];

}

}

AFTER OPTIMIZATION

for (i=0; i<N; i++)

for (j=0; j<M; j++)

{

Zbinduct = i*M+j;

*(Zptr+Zbinduct)=*(bptr+

Z binduct);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit3part2-200903161624/75/Unit-3-part2-19-2048.jpg)

![Array conflicts in cache

a[0,0]

b[0,0]

main memory cache

1024 4099

...

1024

4099](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit3part2-200903161624/75/Unit-3-part2-22-2048.jpg)