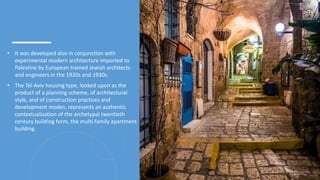

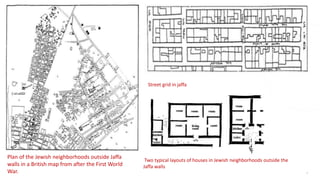

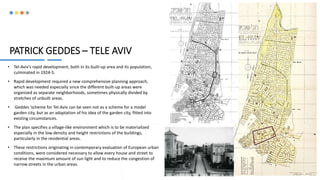

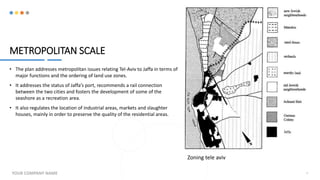

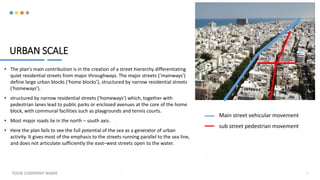

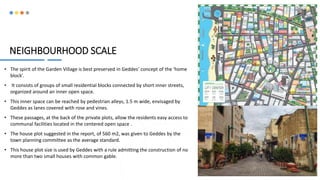

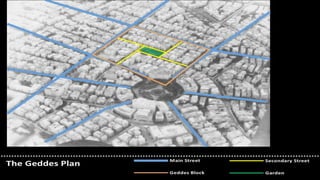

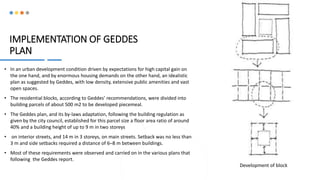

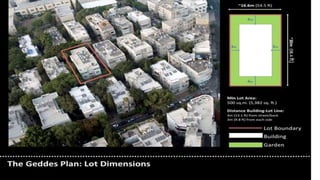

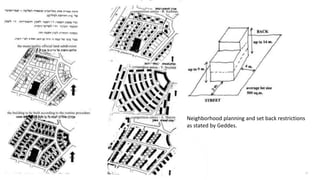

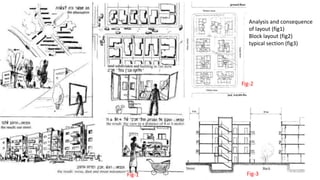

The document outlines the development of Tel Aviv, emphasizing its urban spaces shaped by buildings and residential architecture, particularly influenced by European modernism in the 1920s and 1930s. It discusses Patrick Geddes' planning approach, which aimed to create a green environment and a structured urban layout, consisting of quiet residential streets and communal spaces while integrating traditional Mediterranean forms. The plan addressed metropolitan issues, zoning, and building regulations to ensure a balance between urban density and the quality of life for residents.