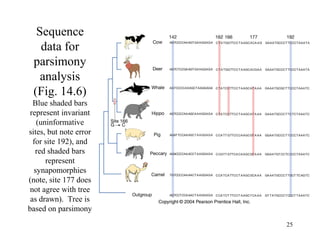

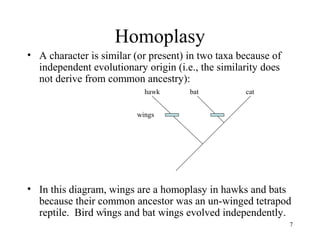

Phylogenetic trees reconstruct evolutionary relationships by grouping taxa with shared derived characteristics inherited from recent common ancestors. This document discusses methods for building phylogenetic trees, including cladistics which uses shared derived homologies (synapomorphies) to determine relationships. It also examines evidence for the evolutionary relationships of whales. Molecular studies of transposable elements and additional fossil evidence support whales evolving from artiodactyl ancestors, rather than being the sister group to artiodactyls.

![12

Two kinds of homology – 2

• Shared derived homology — a trait found in some

members of a group for which we are making a

phylogenetic tree (and which was NOT present in the

common ancestor of the entire group) — synapomorphy

– For example: hair is (potentially) a shared derived homology in the

group [dogs, humans, lizards]

– Synapomorphies DO provide phylogenetic information about

relationships within the group being studied

– In this particular case, if hair is a synapomorphy in dogs and

humans, then dogs and humans share a common ancestor that is

not shared with lizards, and the common dog-human ancestor must

have lived more recently than the common ancestor of all three

taxa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-12-320.jpg)

![13

A tree for [dogs, humans, lizards] – 1

lizard human dog

hair

backbone

• The TWO major assumptions that we are making

when we build this tree are:

1) hair is homologous in humans and dogs

2) hair is a derived trait within tetrapods](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-13-320.jpg)

![14

A tree for [dogs, humans, lizards] – 2

lizard human dog

hair

backbone

• In the absence of other information, the assumption of

homology of hair in humans and dogs is justified by

parsimony (fewest number of evolutionary steps is

most likely = simplest explanation)

• Also we can check to see that hair is formed in the

same way by the same kinds of cells, etc.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-14-320.jpg)

![15

A tree for [dogs, humans, lizards] – 3

• These trees (in which hair is considered a homoplasy

in dogs and humans) are less parsimonious than the

one on the previous slide, because they require two

independent evolutionary origins of hair

human lizard dog

hair

backbone

hair

dog lizard human

hair

backbone

hair](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-15-320.jpg)

![18

Outgroups – 2

• In the present example, [dog, human, lizard] are

all amniote tetrapods. The anamniote tetrapods

(amphibia) make a reasonable outgroup for this

problem

• No amphibia have hair, therefore absence of hair

[amphibia, lizards] is primitive (plesiomorphic)

and presence of hair [dogs, humans] is derived

(apomorphic)

• So, presence of hair is a shared derived character

(synapomorphy), and dogs and humans are more

closely related to each other than either is to

lizards](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-18-320.jpg)

![19

A tree for [dogs, humans, lizards] – 4

• The presence of hair is apomorphic (derived) because

no amphibians have hair

lizard human dog

hair

backbone

Amphibia

amniotic egg](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-19-320.jpg)

![21

A tree for [dogs, humans, lizards] – 5

• Tree (a) is most parsimonious, so we’ll take that as our best

estimate of the true phylogeny of [dog, human, lizard]

• Of course, if we studied different characters, or used a different

outgroup, our phylogenetic tree could change

human lizard dog

hair

backbone

hair

dog lizard human

hair

backbone

hair

lizard human dog

hair

backbone

(a)

(b)

(c)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-21-320.jpg)

![23

The

Artiodactlya

hypothesis

for the

evolutionary

relationships

of Cetacea

(Fig. 14.4 a)

Odd-toed

ungulates

(Perissodactyla

[horses, rhinos])

are the outgroup](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phylogeny-140802005657-phpapp01/85/Phylogeny-23-320.jpg)