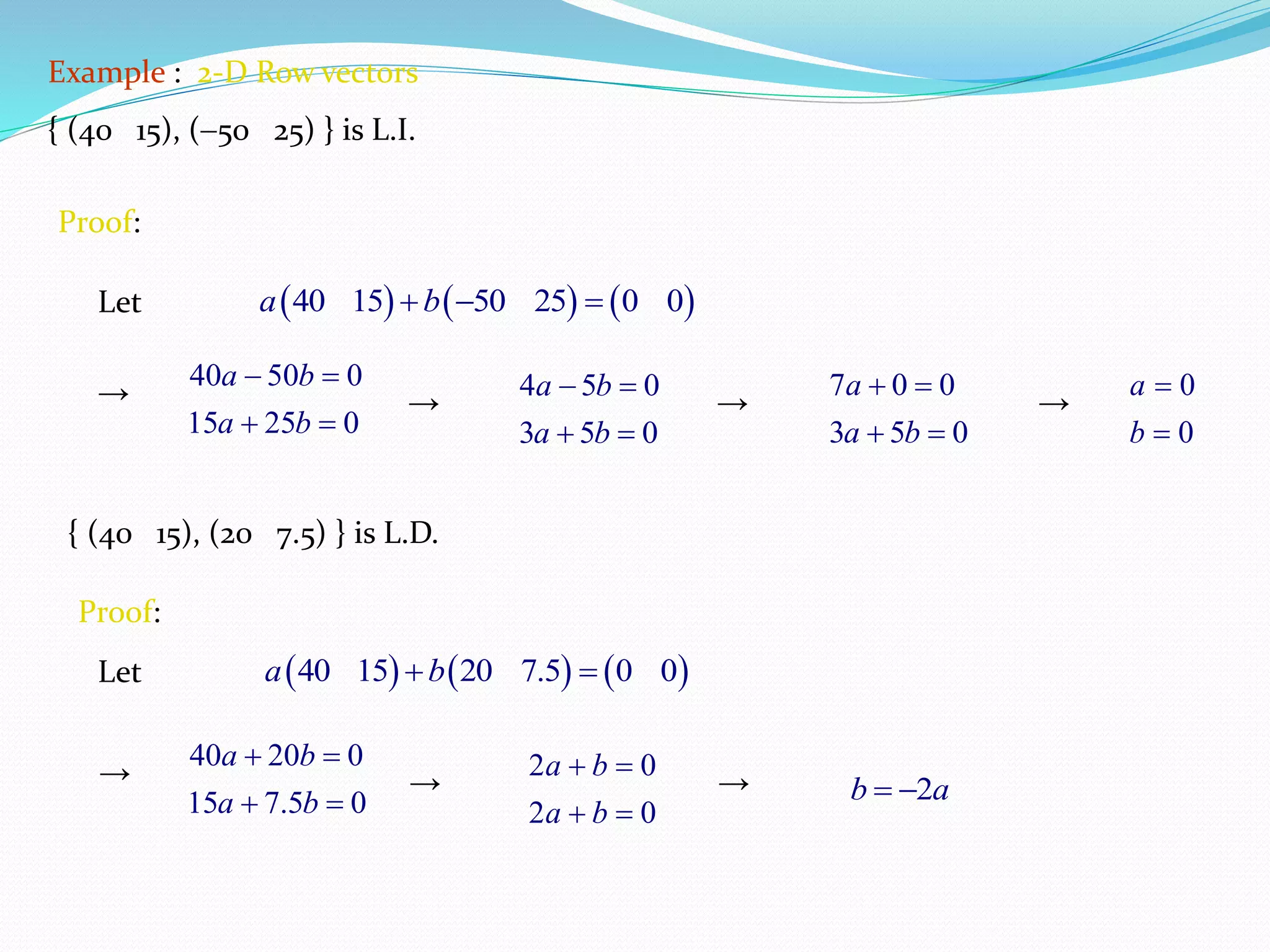

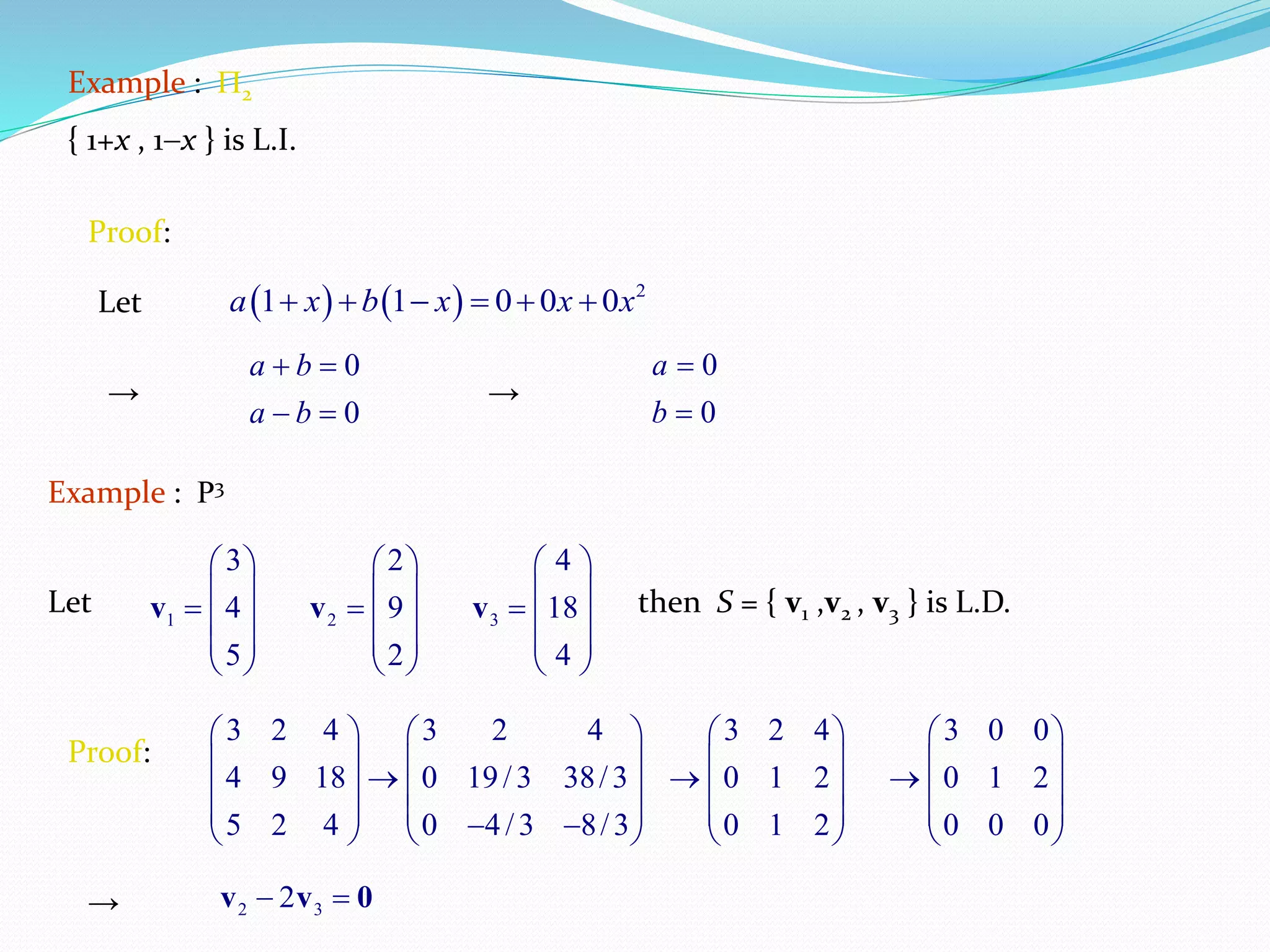

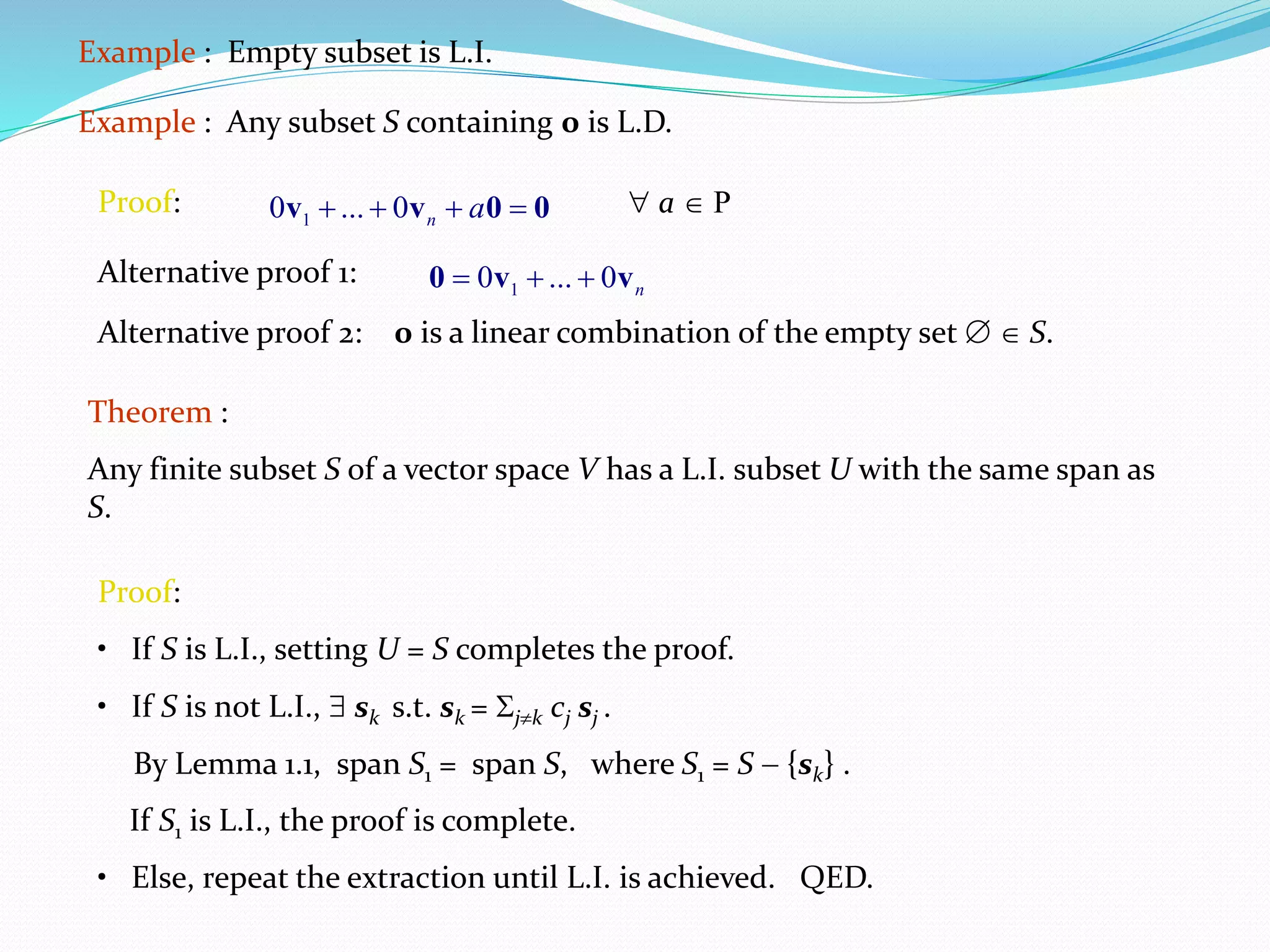

The document discusses linear independence and bases in vector spaces. It defines linear independence as a set of vectors where none can be written as a linear combination of the others. A basis is defined as a linearly independent set of vectors that spans the entire vector space. Several examples are provided to illustrate these concepts, including showing that the vectors (1, 2) and (4, 1) form a basis for R2. The document also discusses properties of linear independence and how it relates to bases being minimal and spanning the entire space.