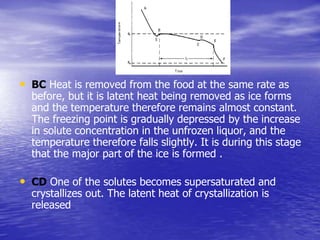

Chilling and freezing are unit operations used to preserve foods by reducing the temperature to extend shelf life. Chilling reduces temperatures to between 1-8°C to slow microbial and biochemical changes, while freezing reduces temperatures below the freezing point of water to immobilize water and further extend shelf life. Properly chilled and frozen foods can be stored for longer periods with minimal quality degradation compared to fresh foods at ambient temperatures.