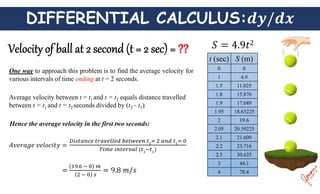

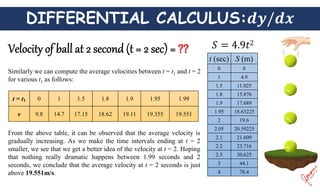

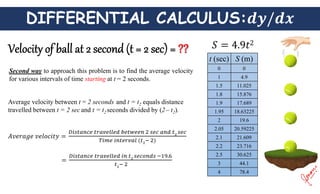

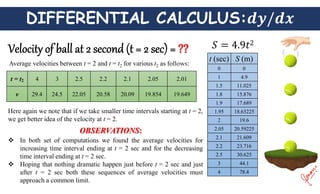

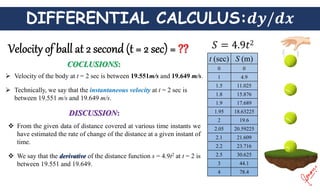

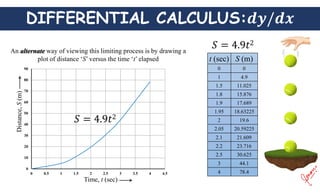

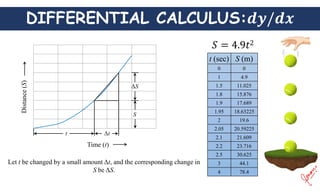

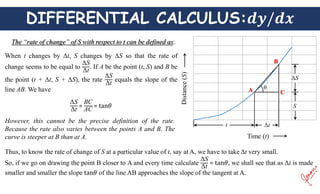

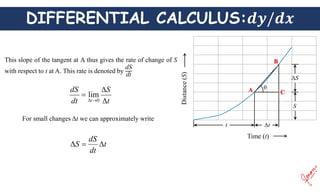

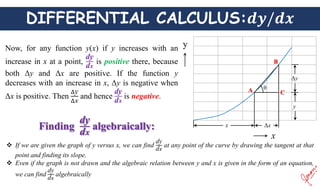

The document discusses differential calculus, particularly focusing on calculating average velocity over specific time intervals and estimating instantaneous velocity at t = 2 seconds. It presents a series of calculations that show that the instantaneous velocity ranges between 19.551 m/s and 19.649 m/s, derived from various approaches to limit time intervals. Additionally, it explains the concept of derivatives and their application in estimating the rate of change of distance with respect to time.

![DIFFERENTIAL CALCULUS:

2

A

, r

rcle

Area of ci

2

)

Δ

(

ΔA

A r

r

]

Δ

2

)

Δ

(

[

ΔA

A 2

2

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

Δ

2

)

Δ

(

ΔA 2

r

r

r

2

Δ

Δ

ΔA

?

A

dr

d

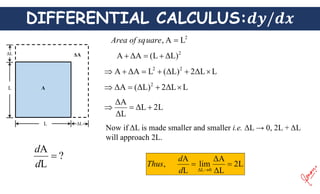

Now if Δr is made smaller and smaller i.e. Δr → 0, 2πr + πΔr

will approach 2πr.

r

r

dr

d

Thus

r

2

Δ

ΔA

lim

A

,

0

Δ

Δr

r

A

ΔA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialcalculus-210714060148/85/Introduction-to-Differential-calculus-13-320.jpg)