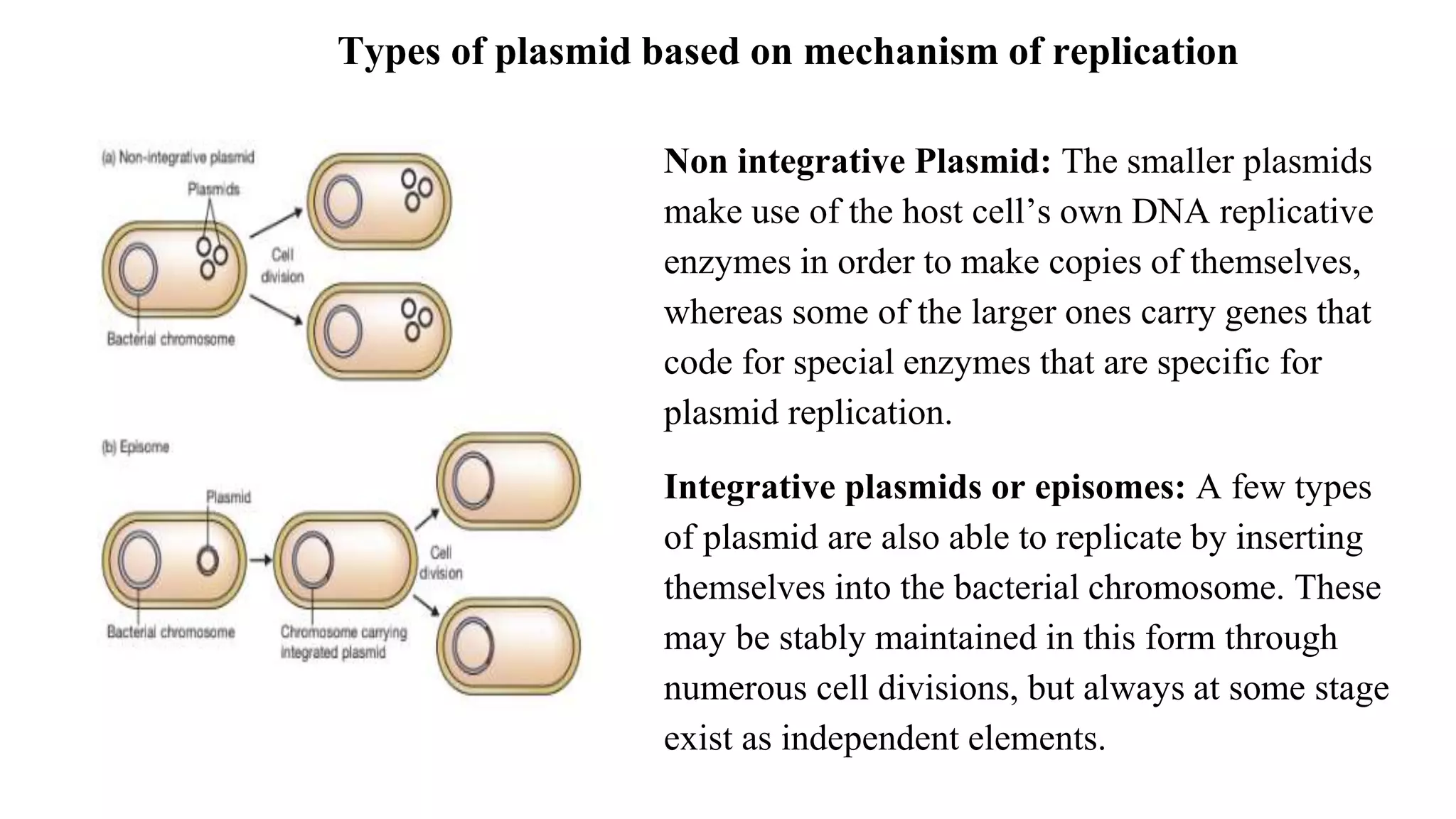

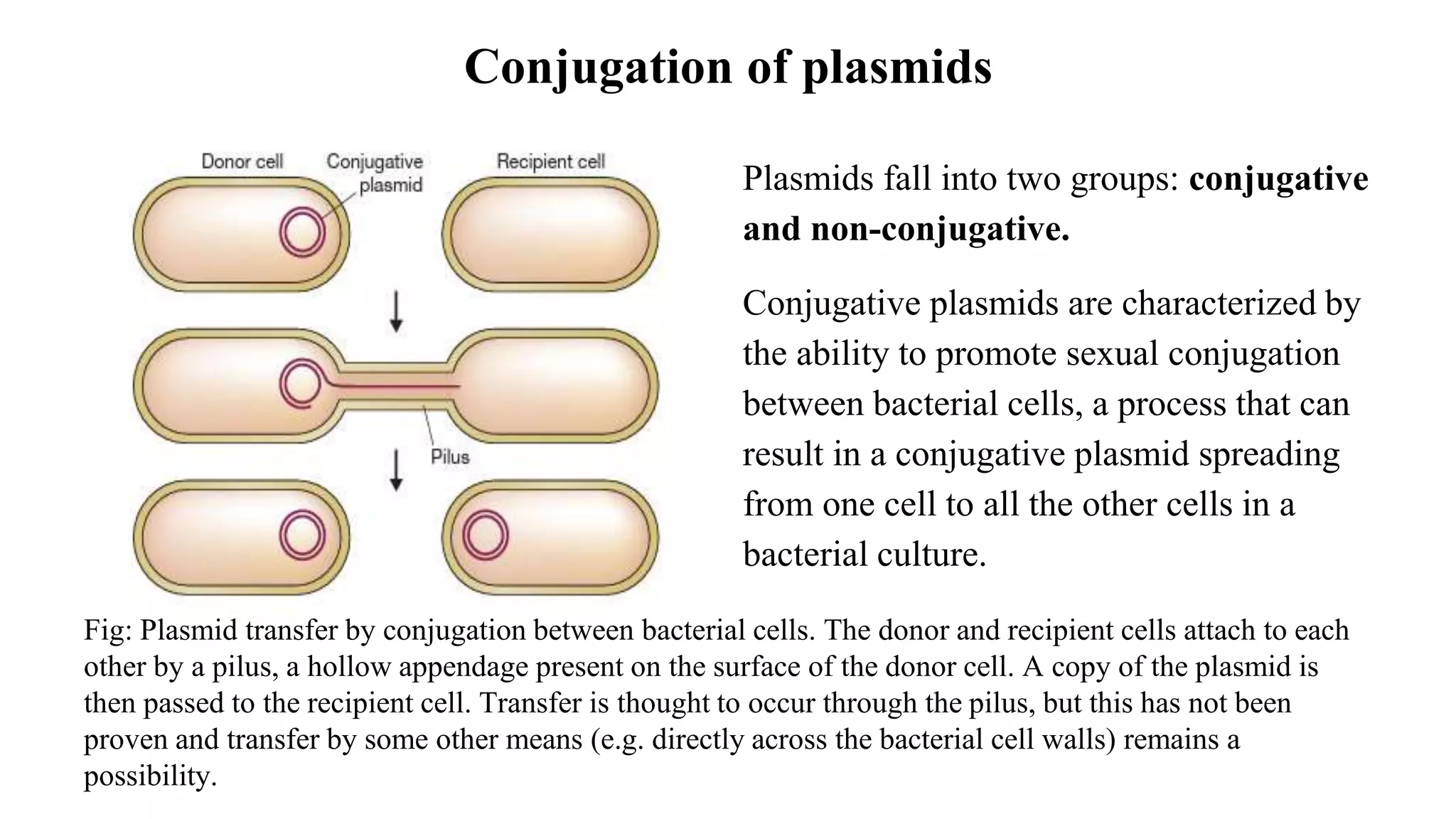

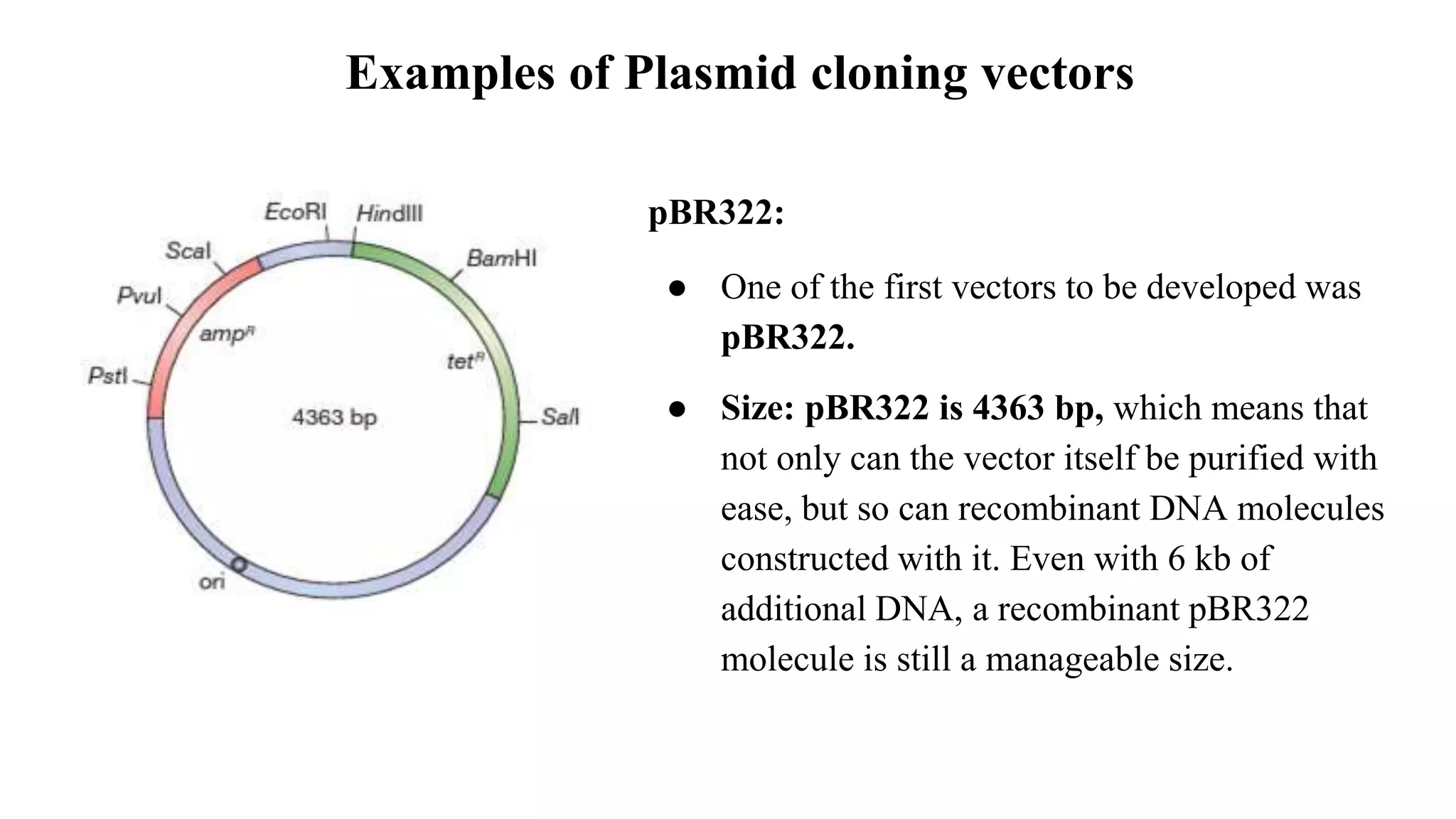

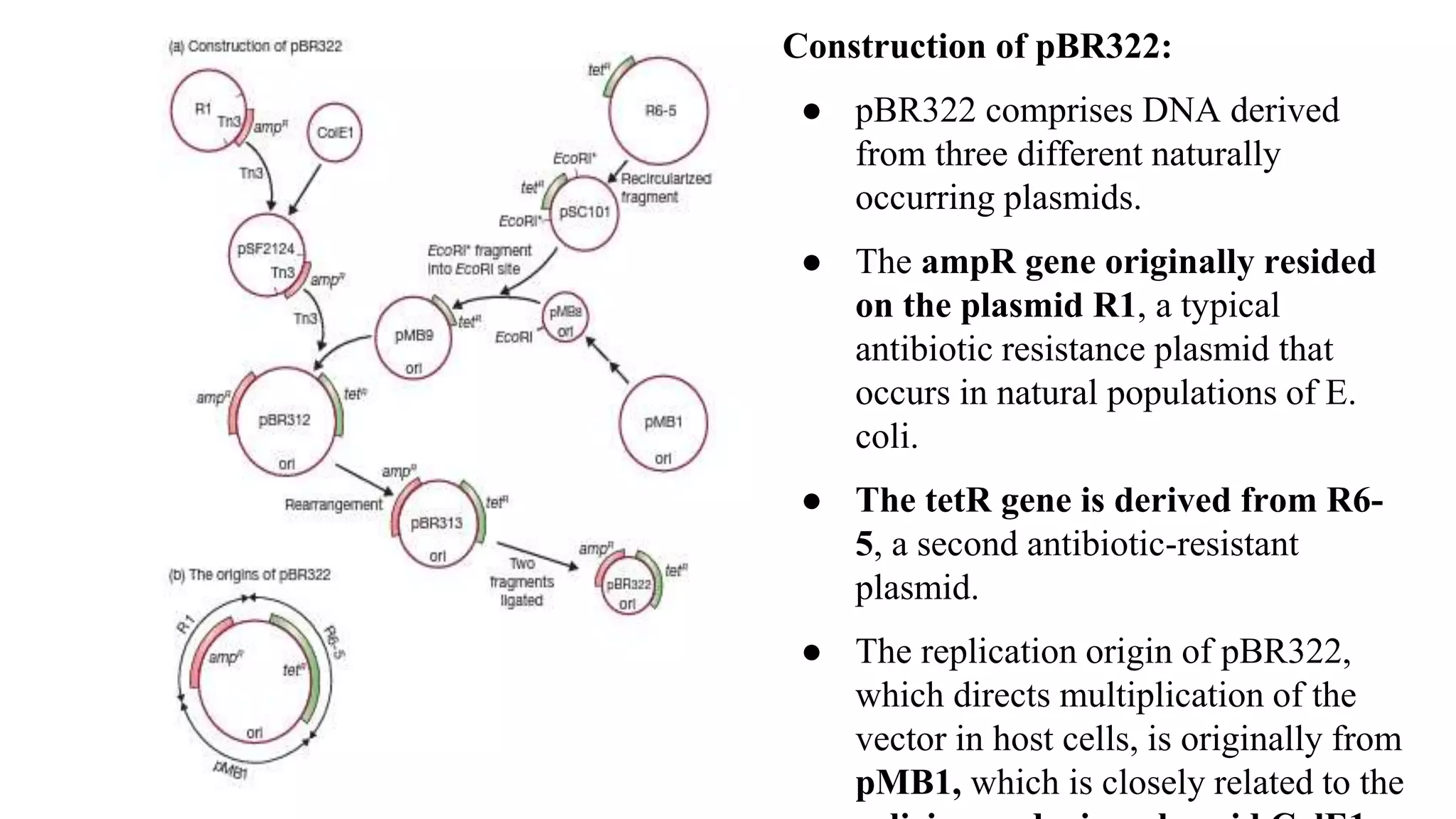

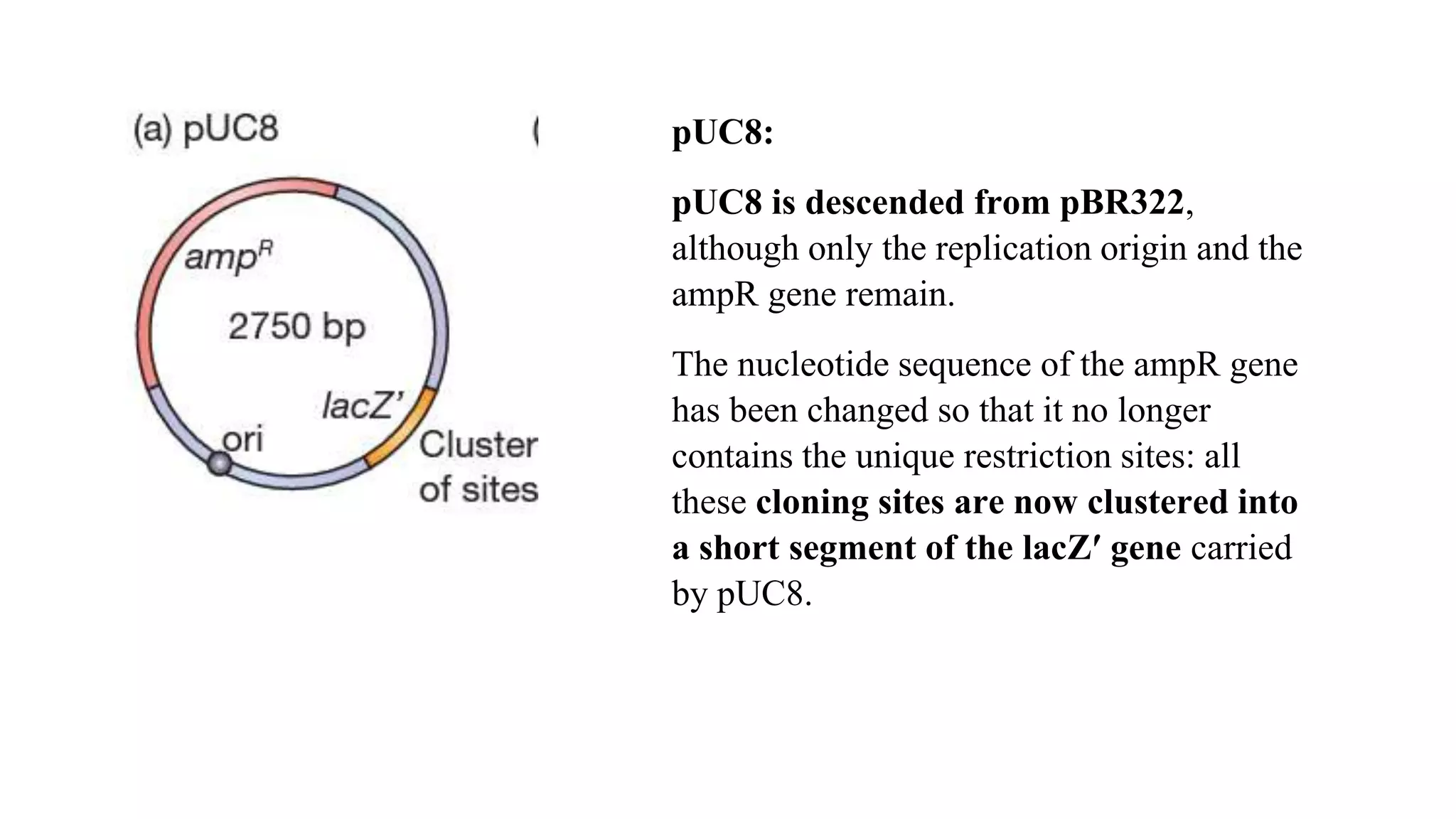

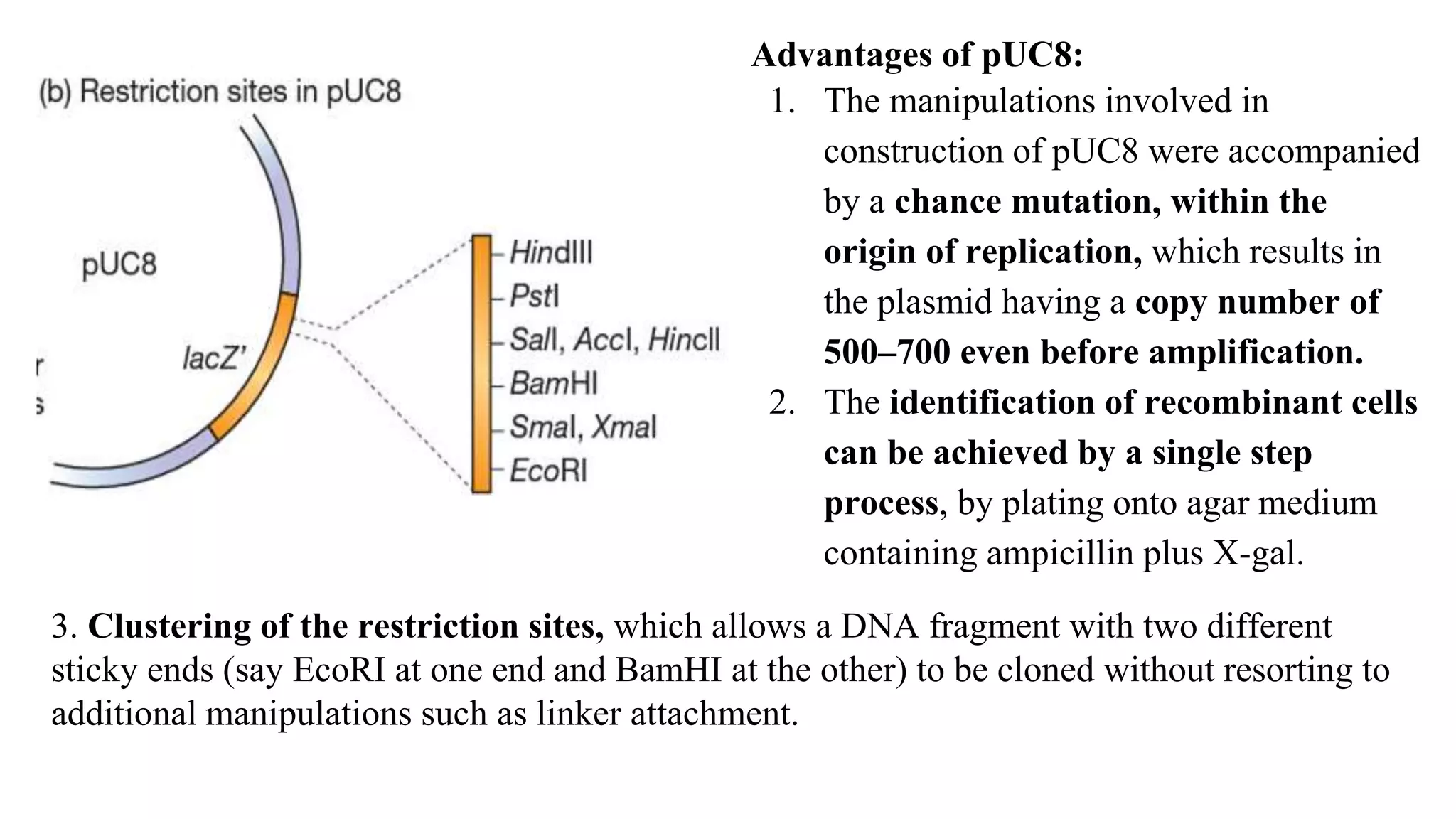

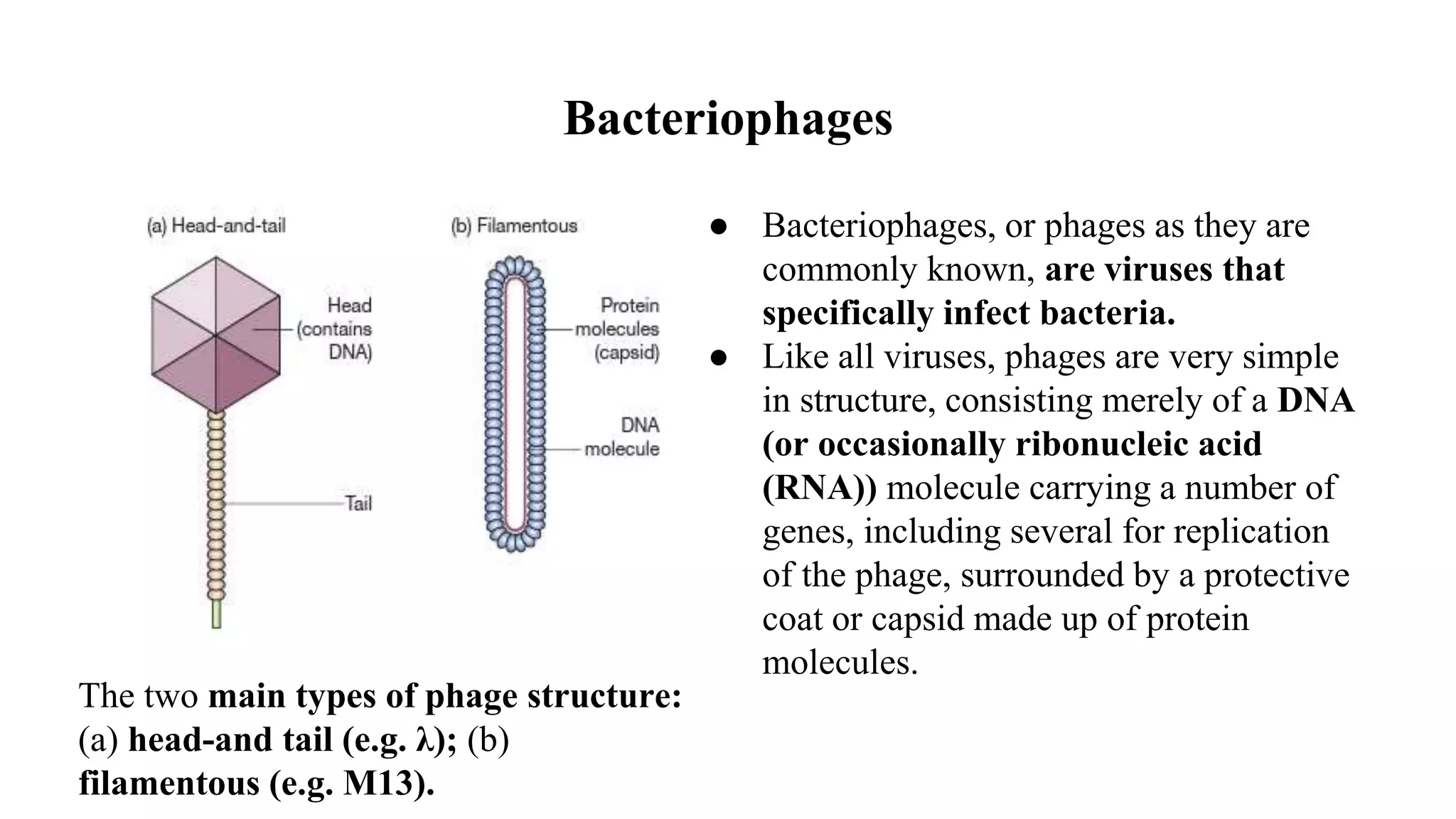

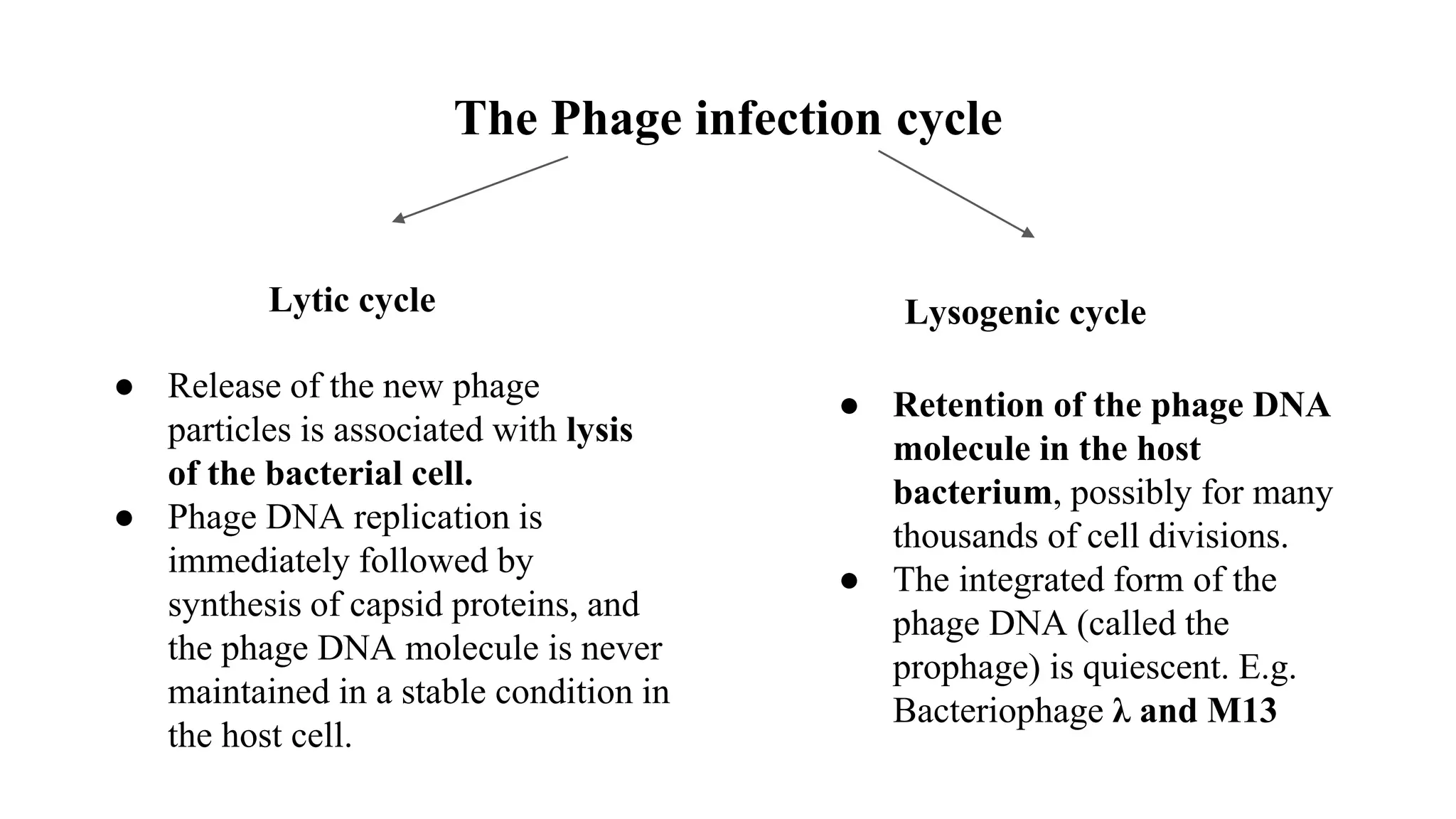

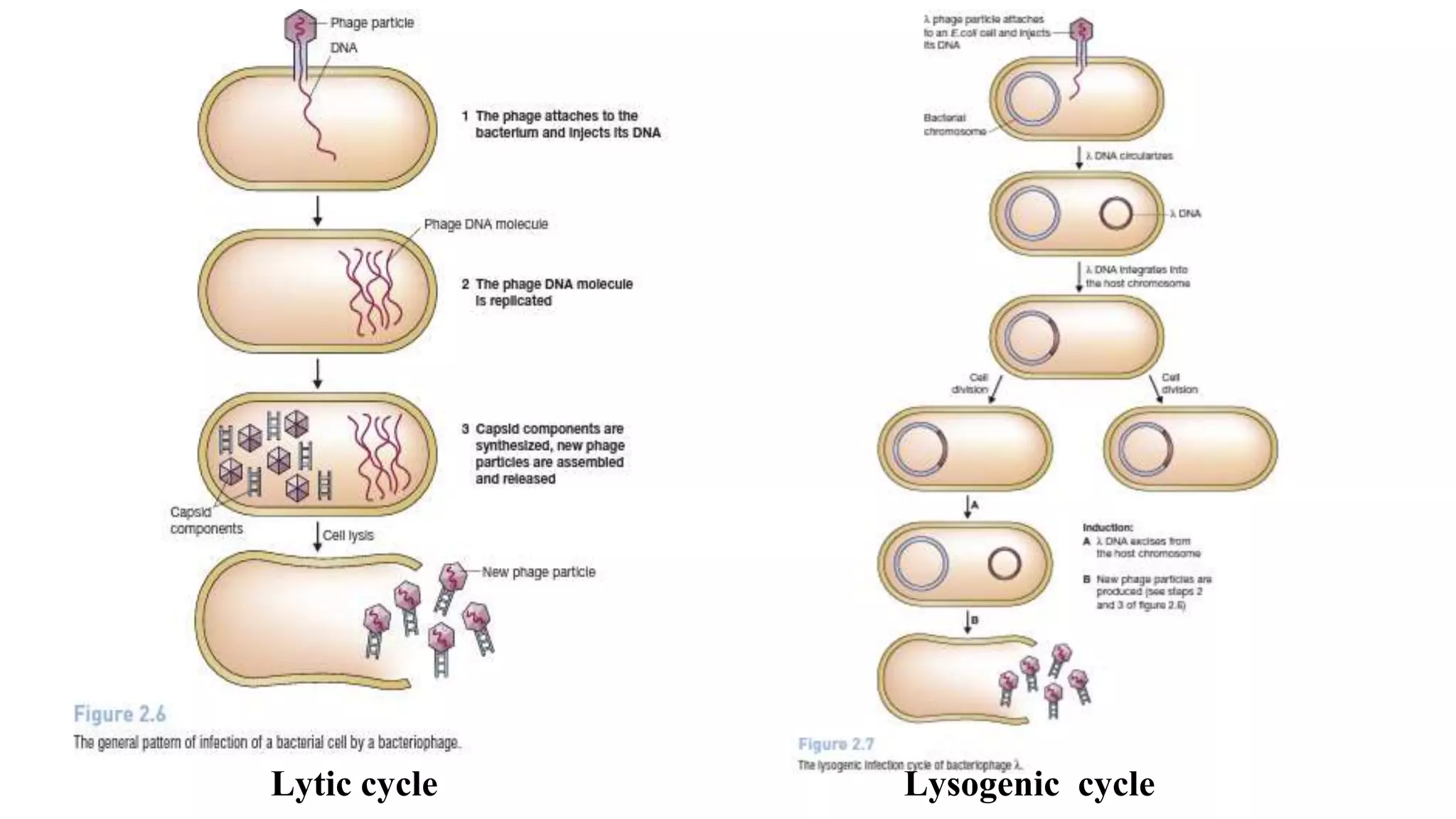

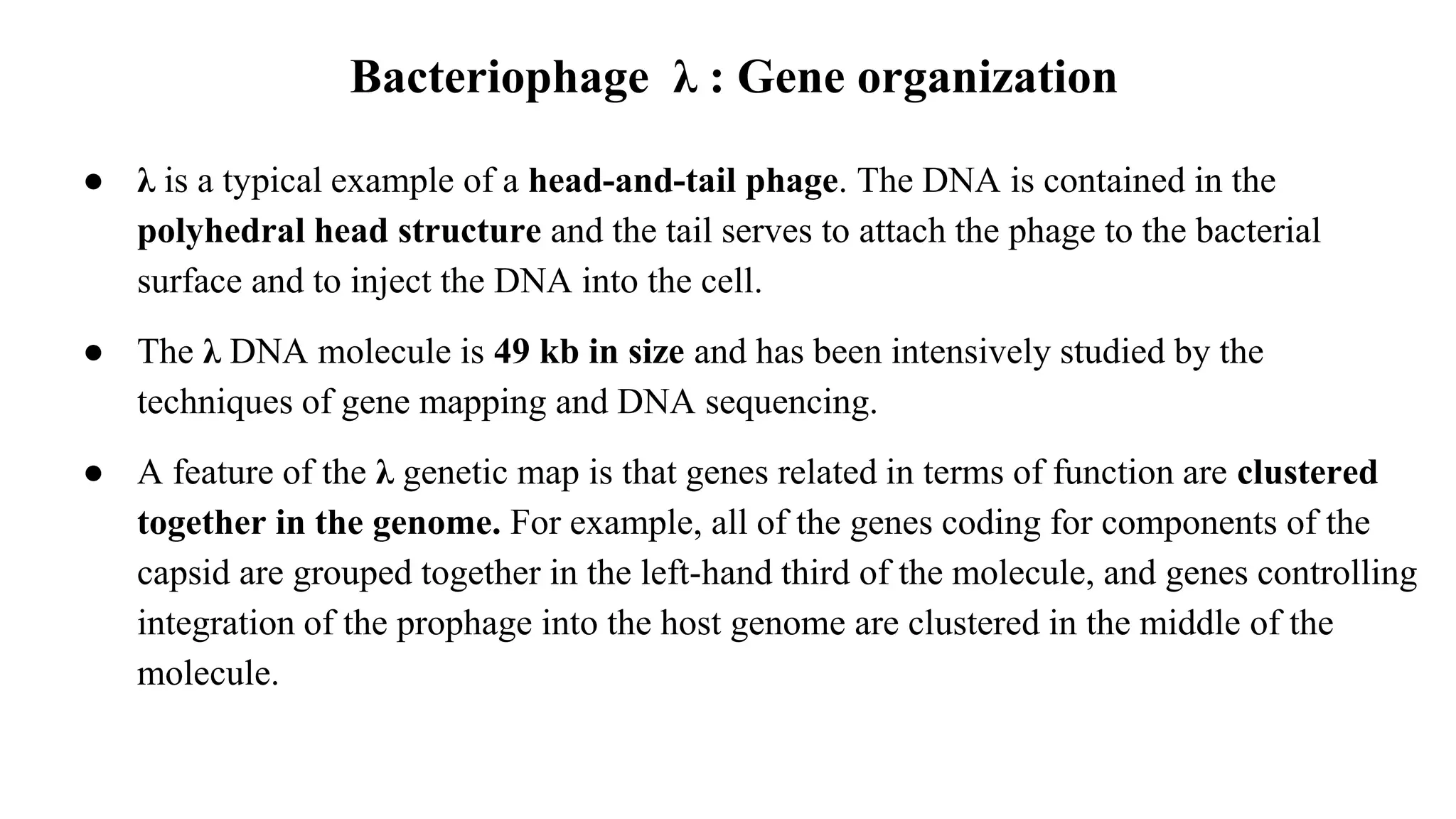

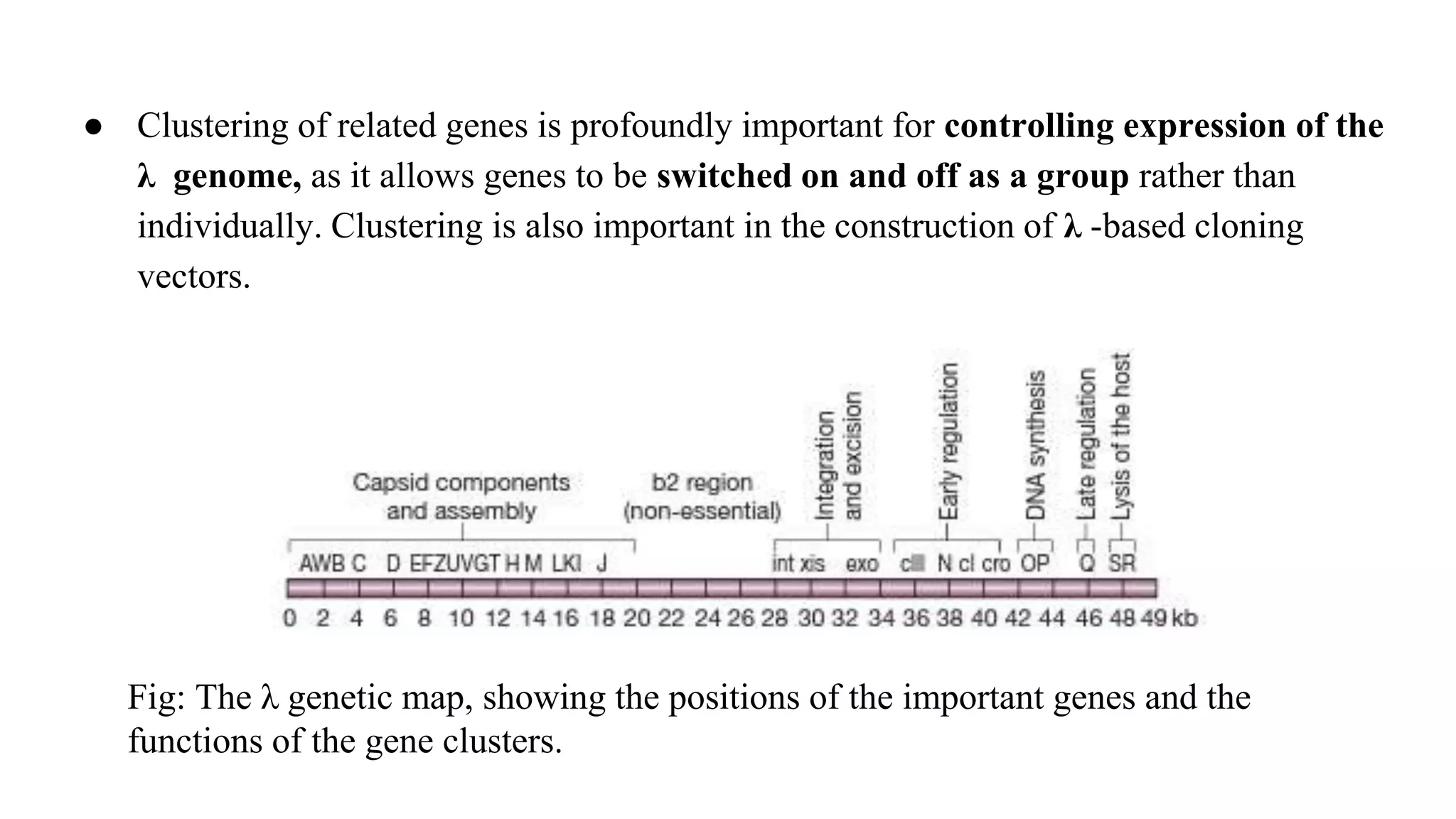

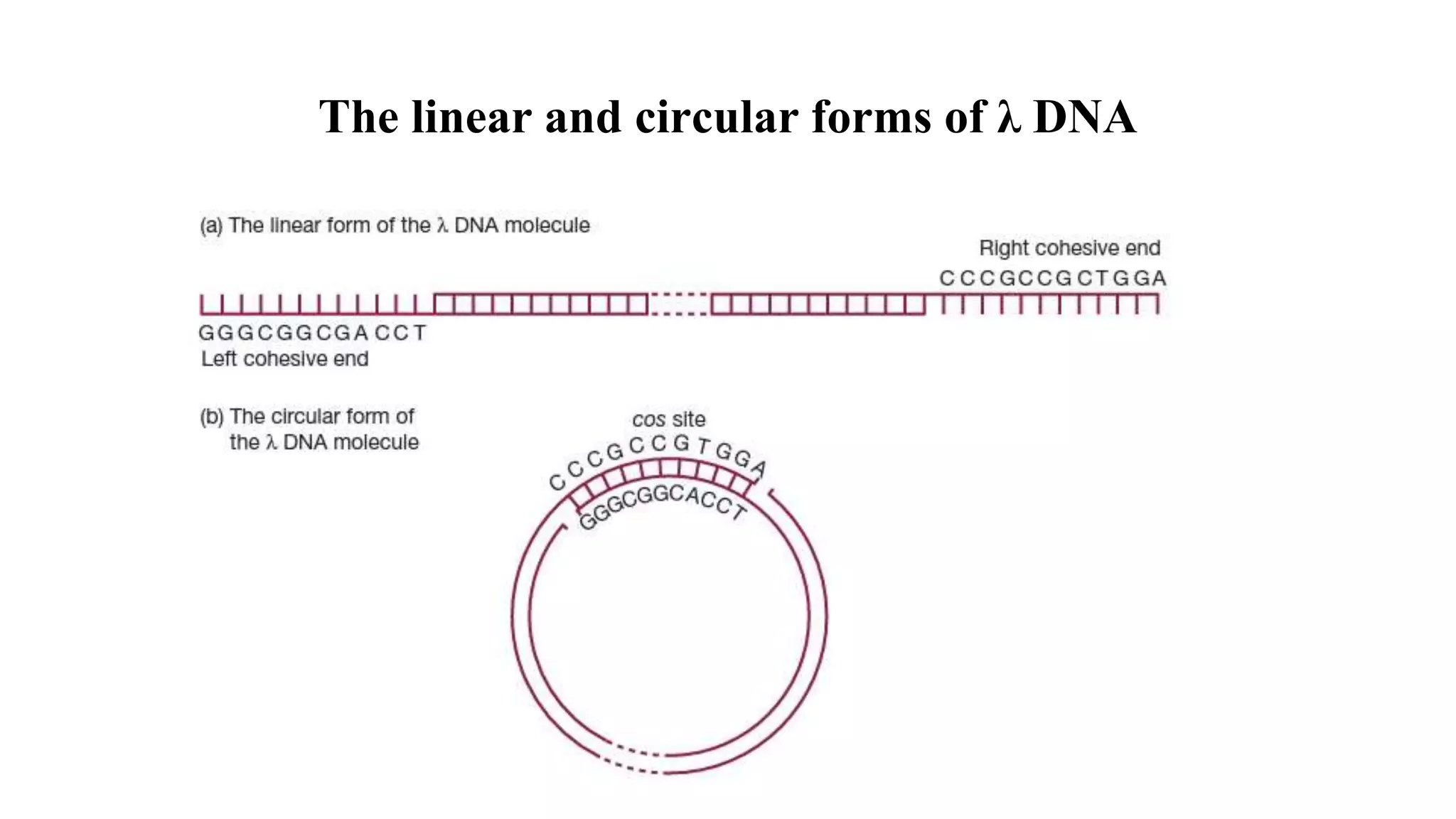

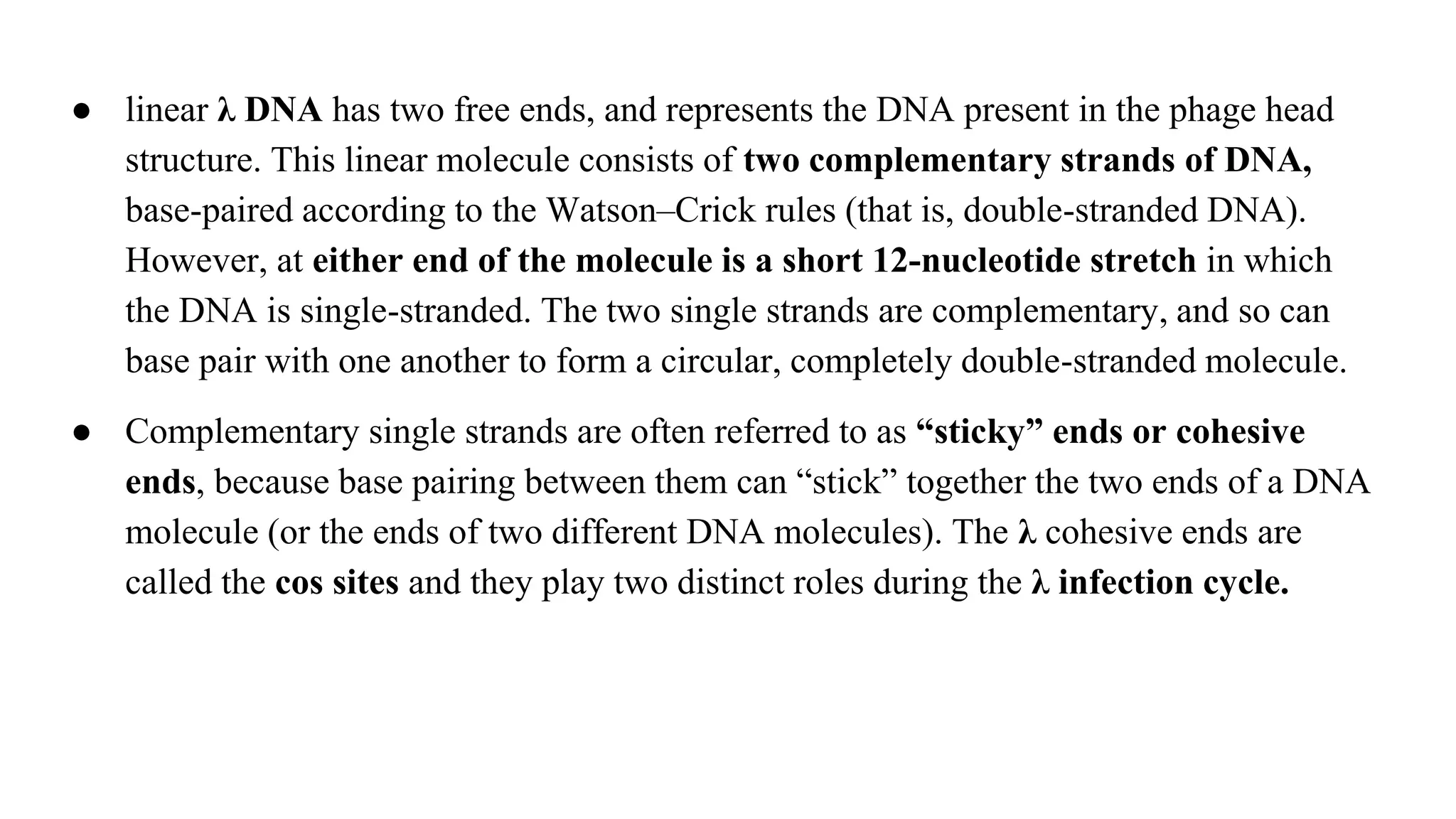

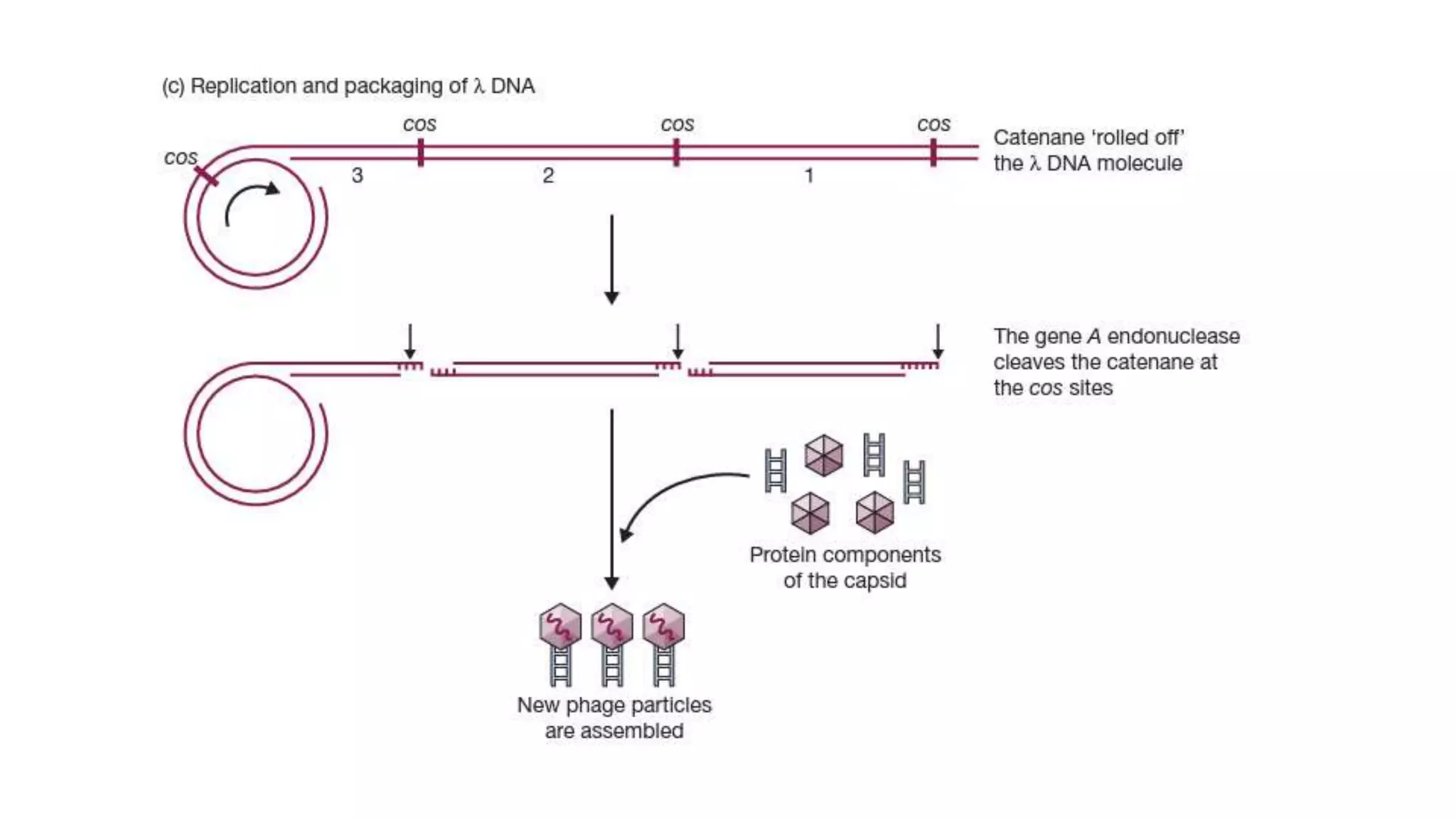

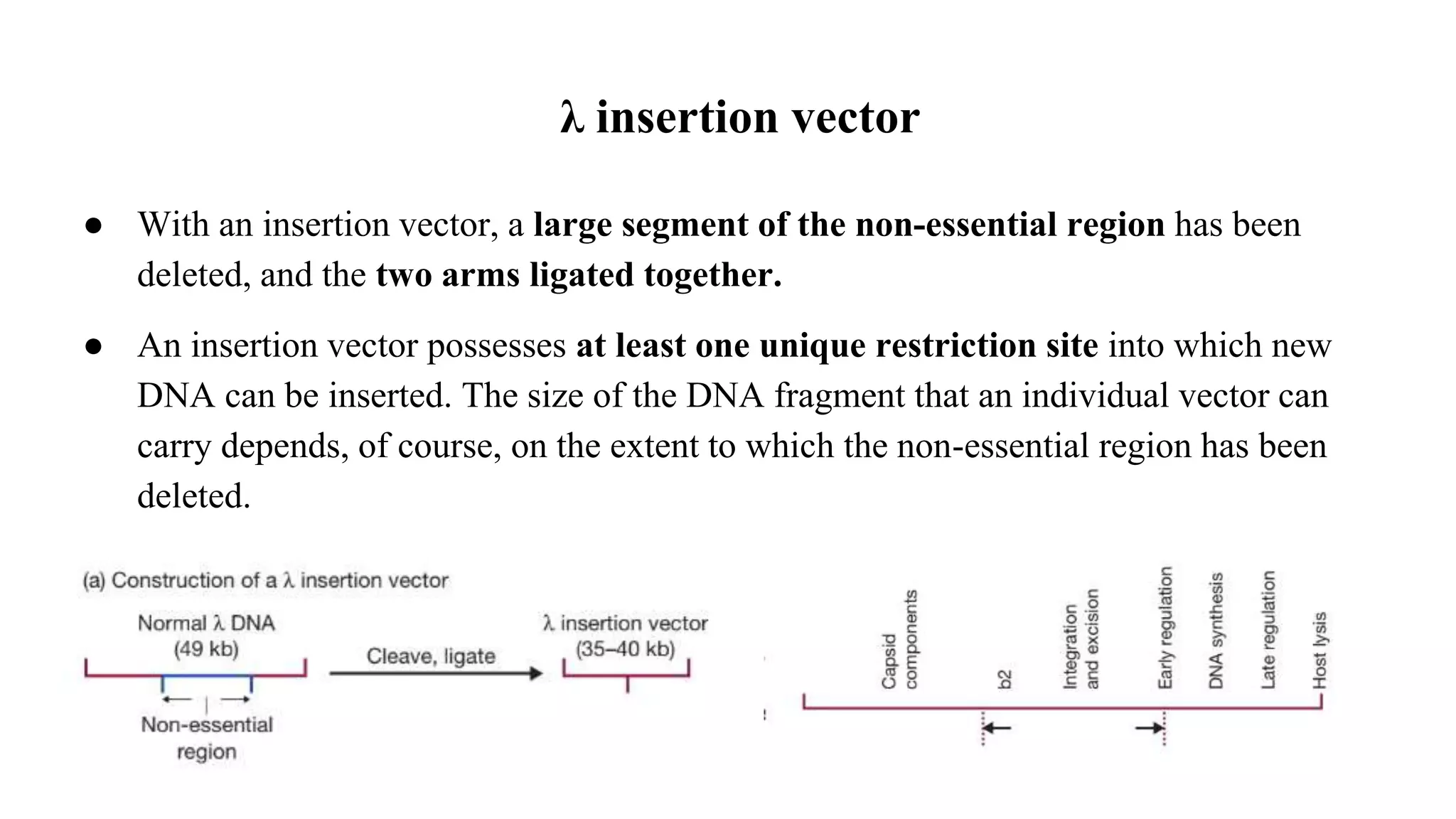

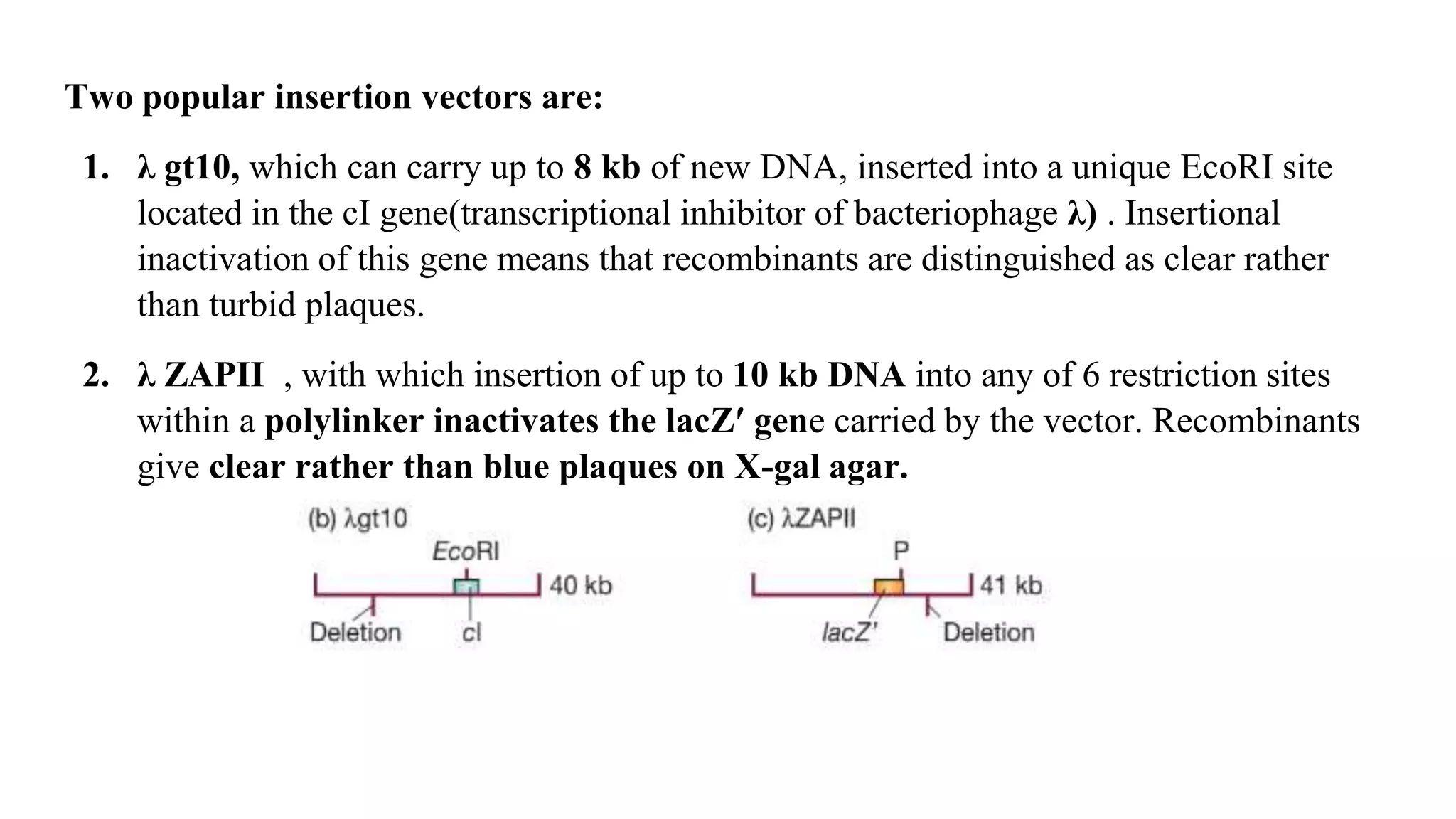

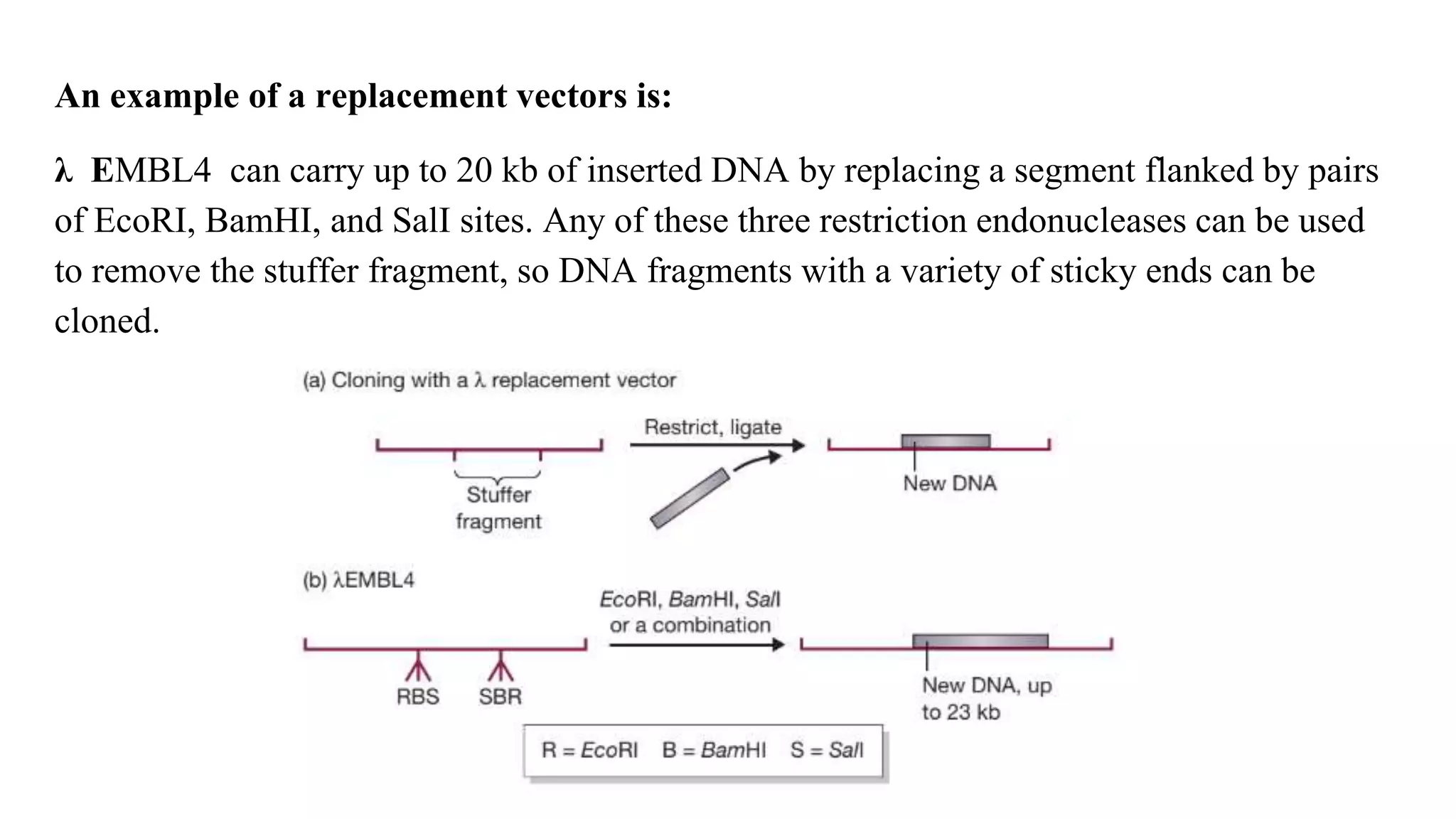

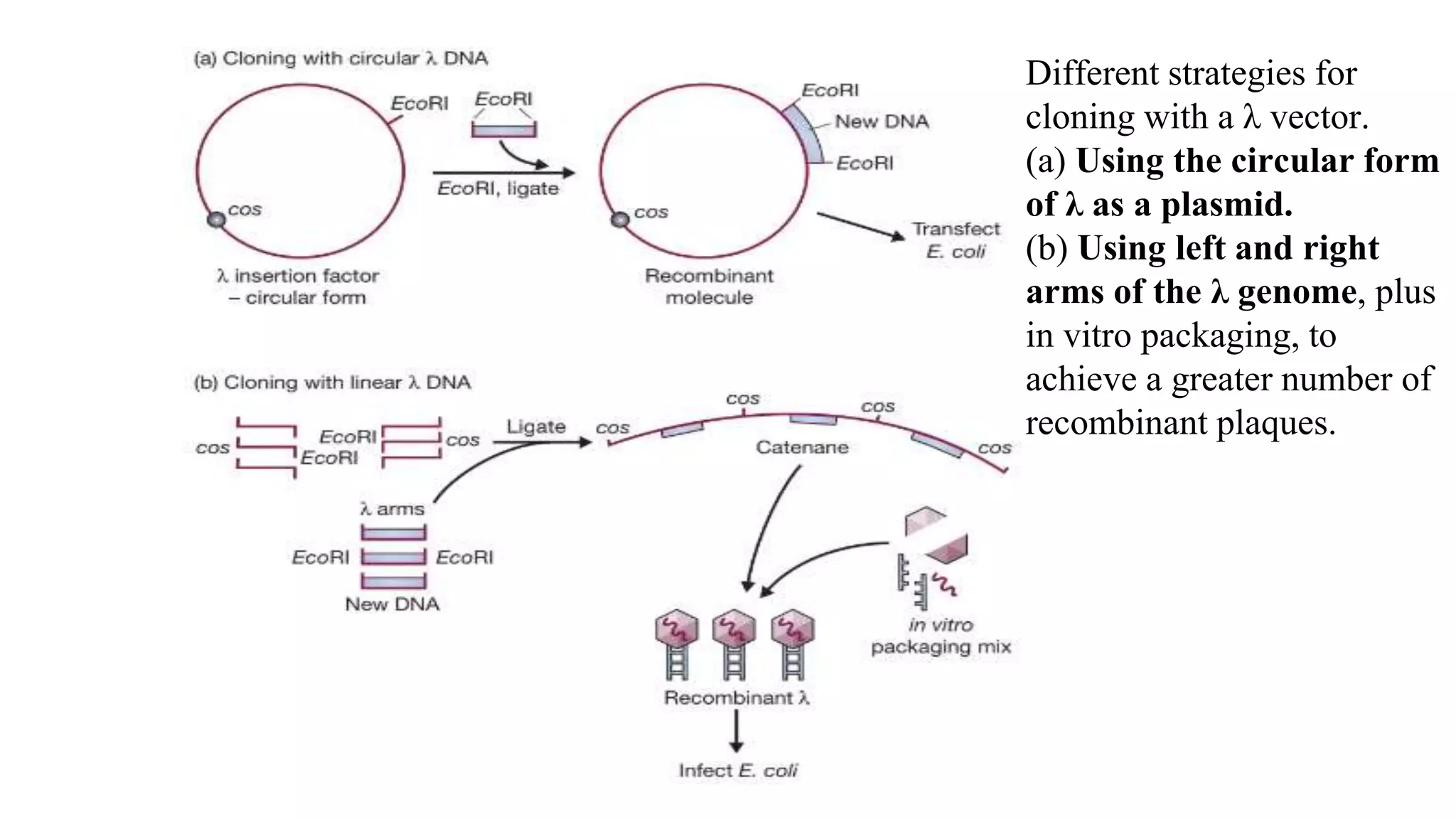

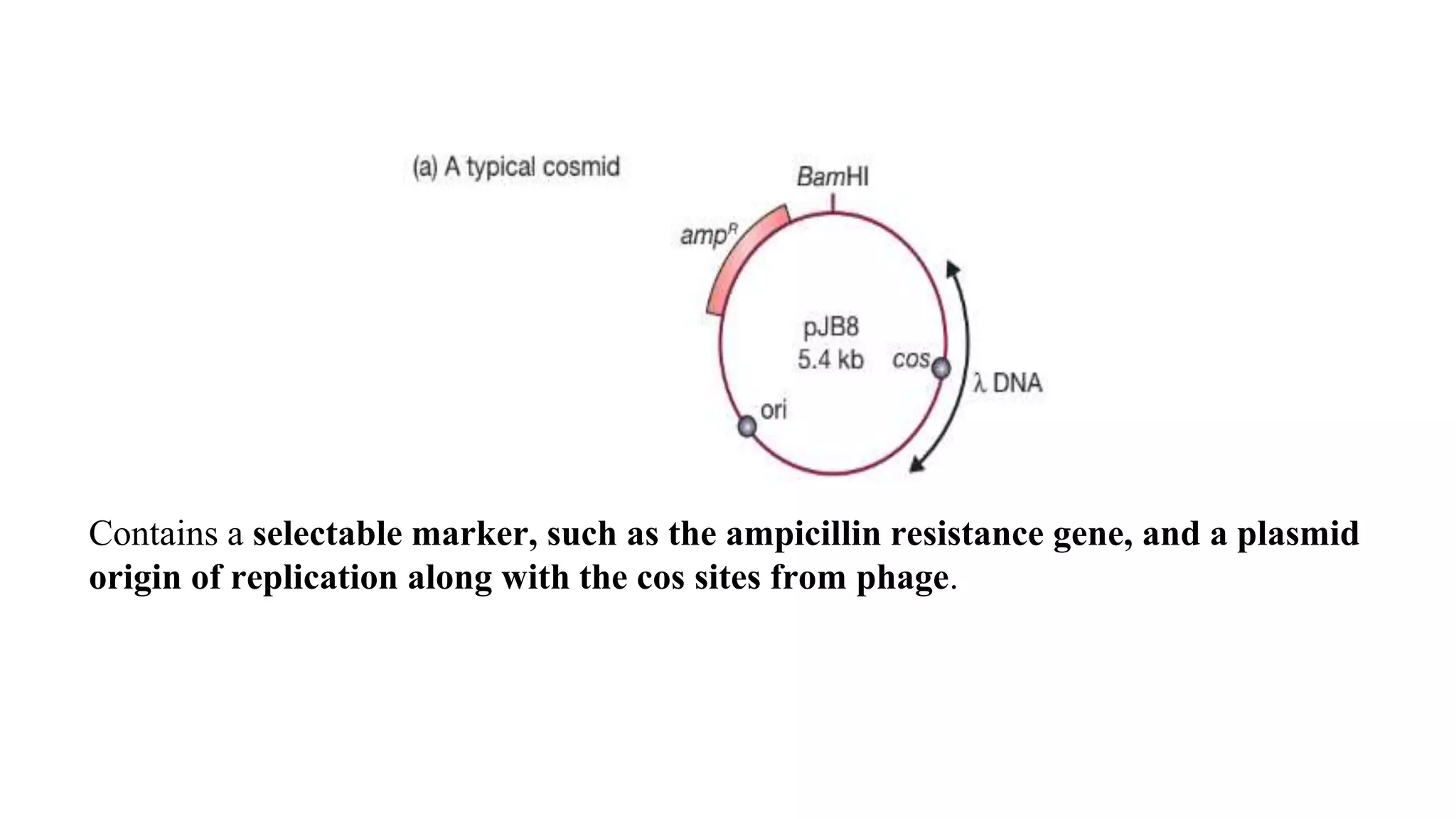

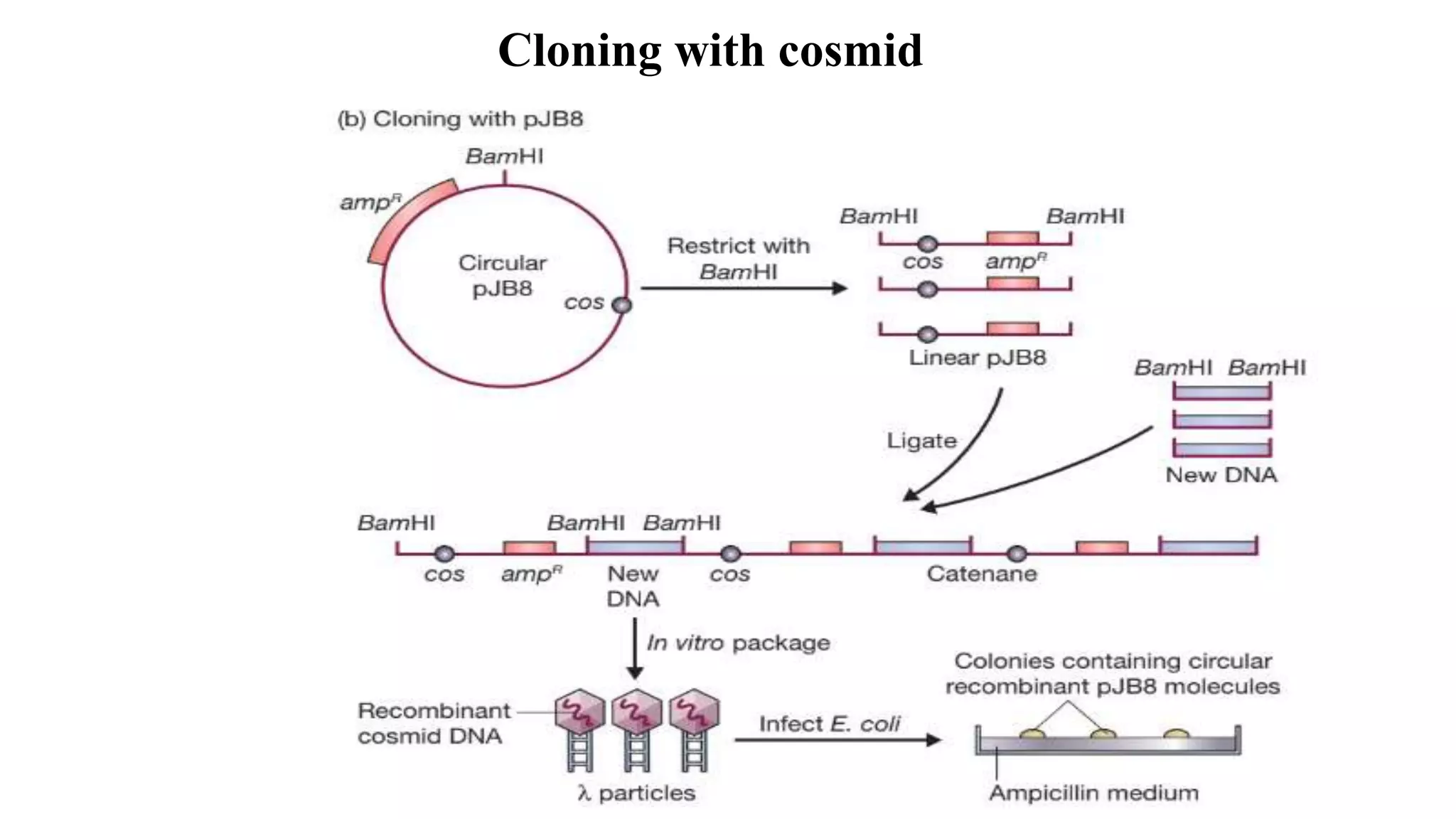

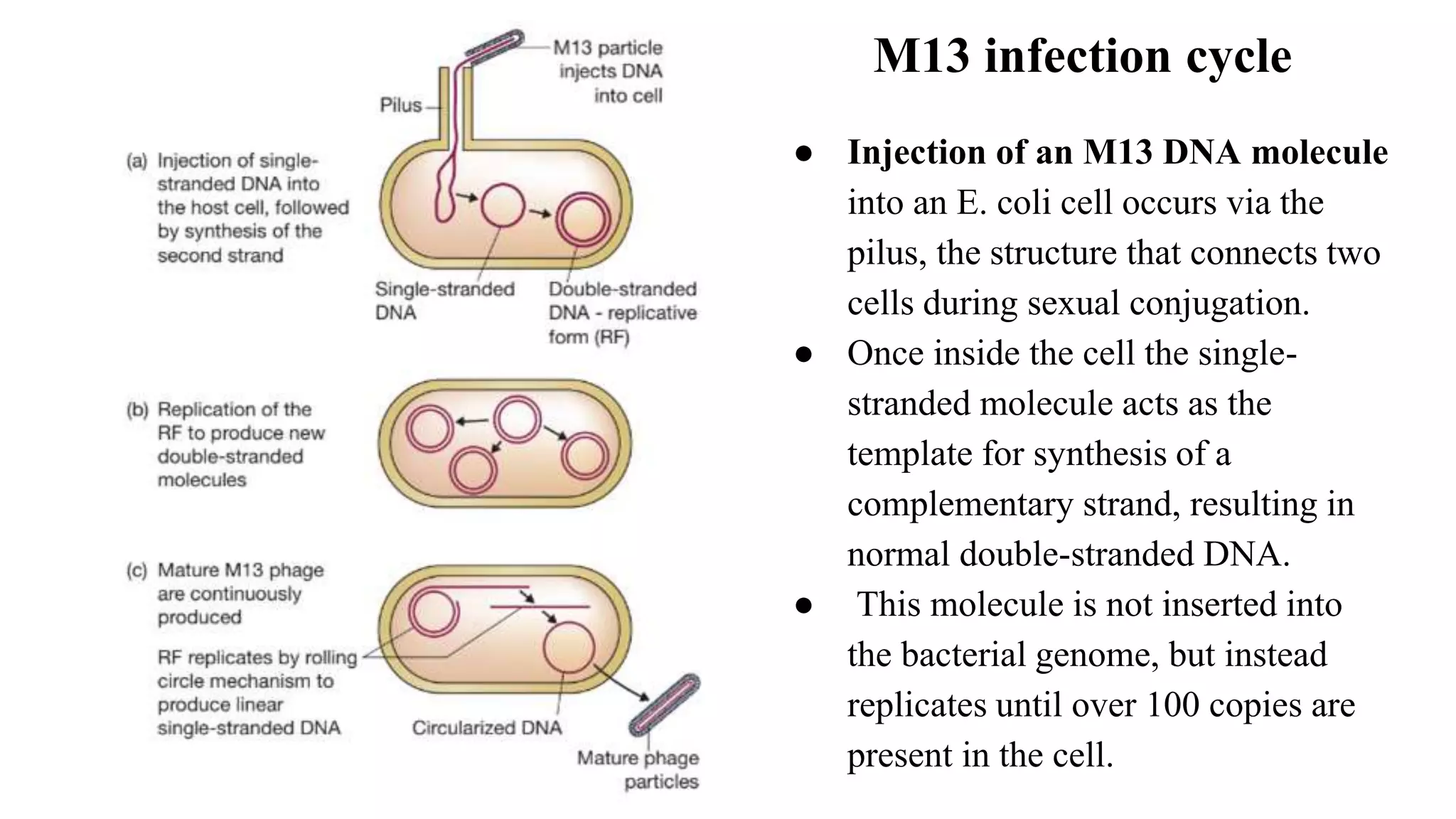

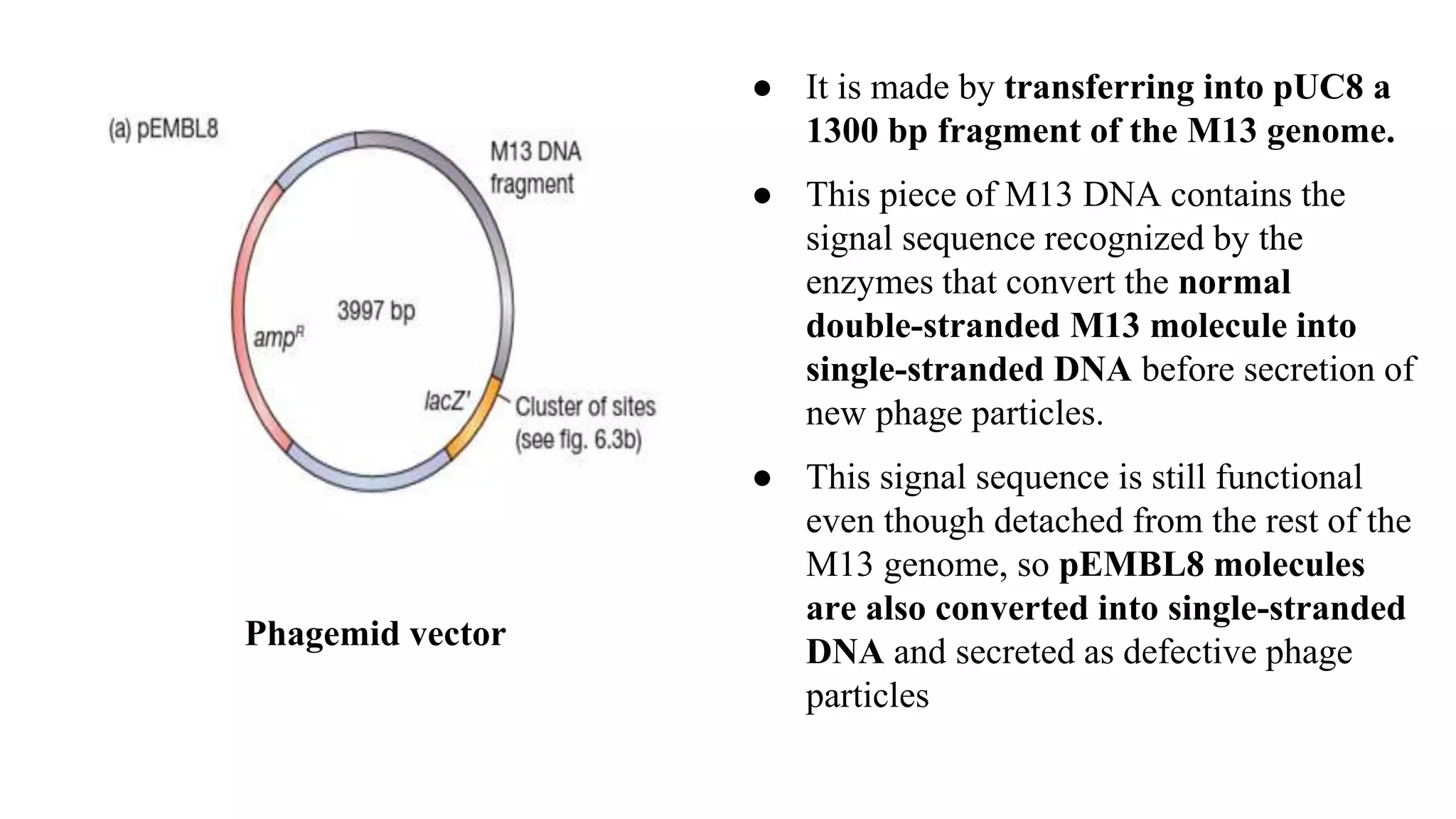

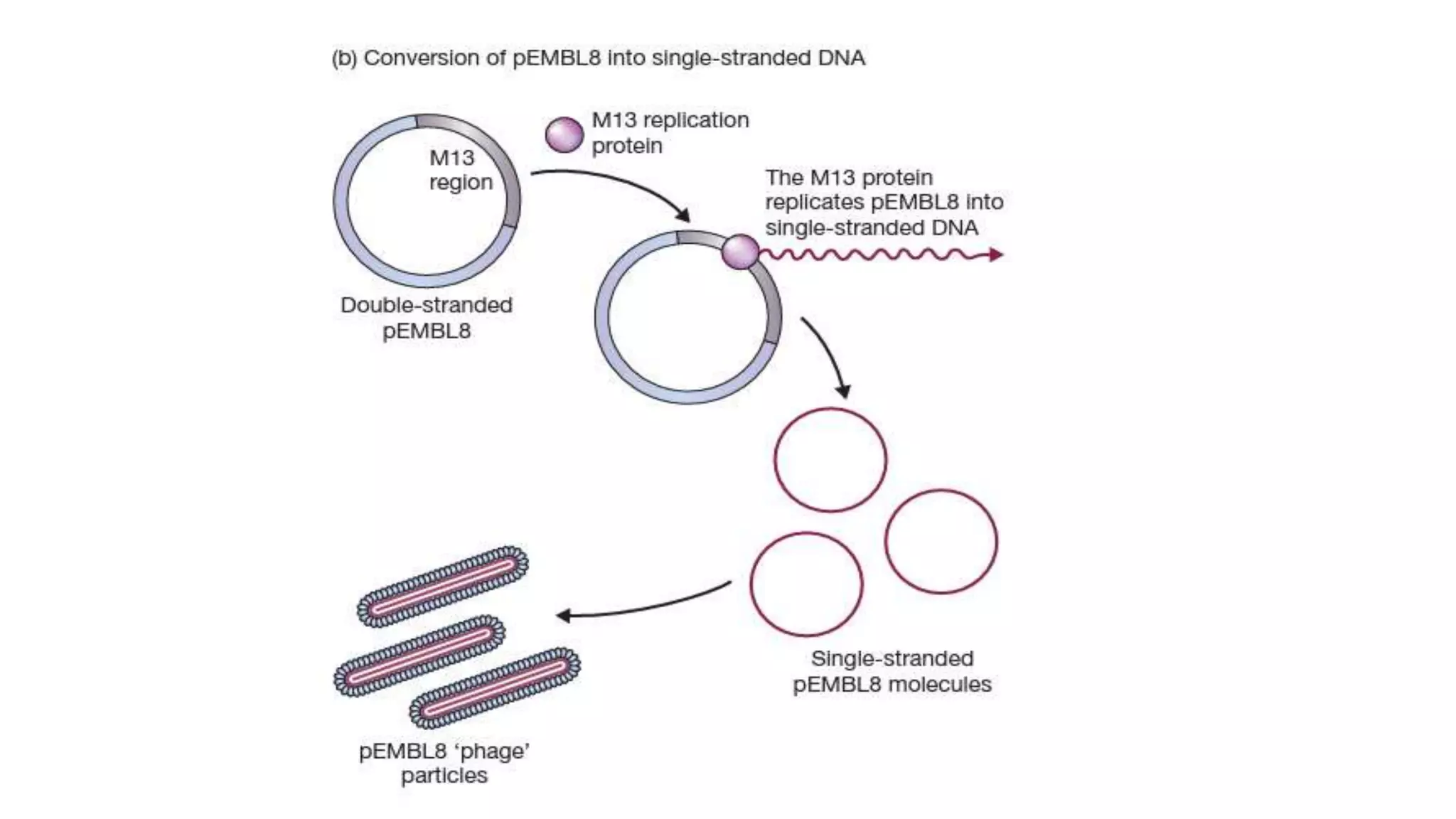

The document discusses various types of cloning vectors, focusing on plasmids and bacteriophages used in genetic engineering. It outlines the criteria for ideal cloning vectors, describes different plasmid types based on their replication mechanisms and functionalities, and explains key examples such as pBR322, pBR327, and cosmids. Additionally, it covers bacteriophages like λ and M13, detailing their structure, replication cycles, and use in cloning procedures.