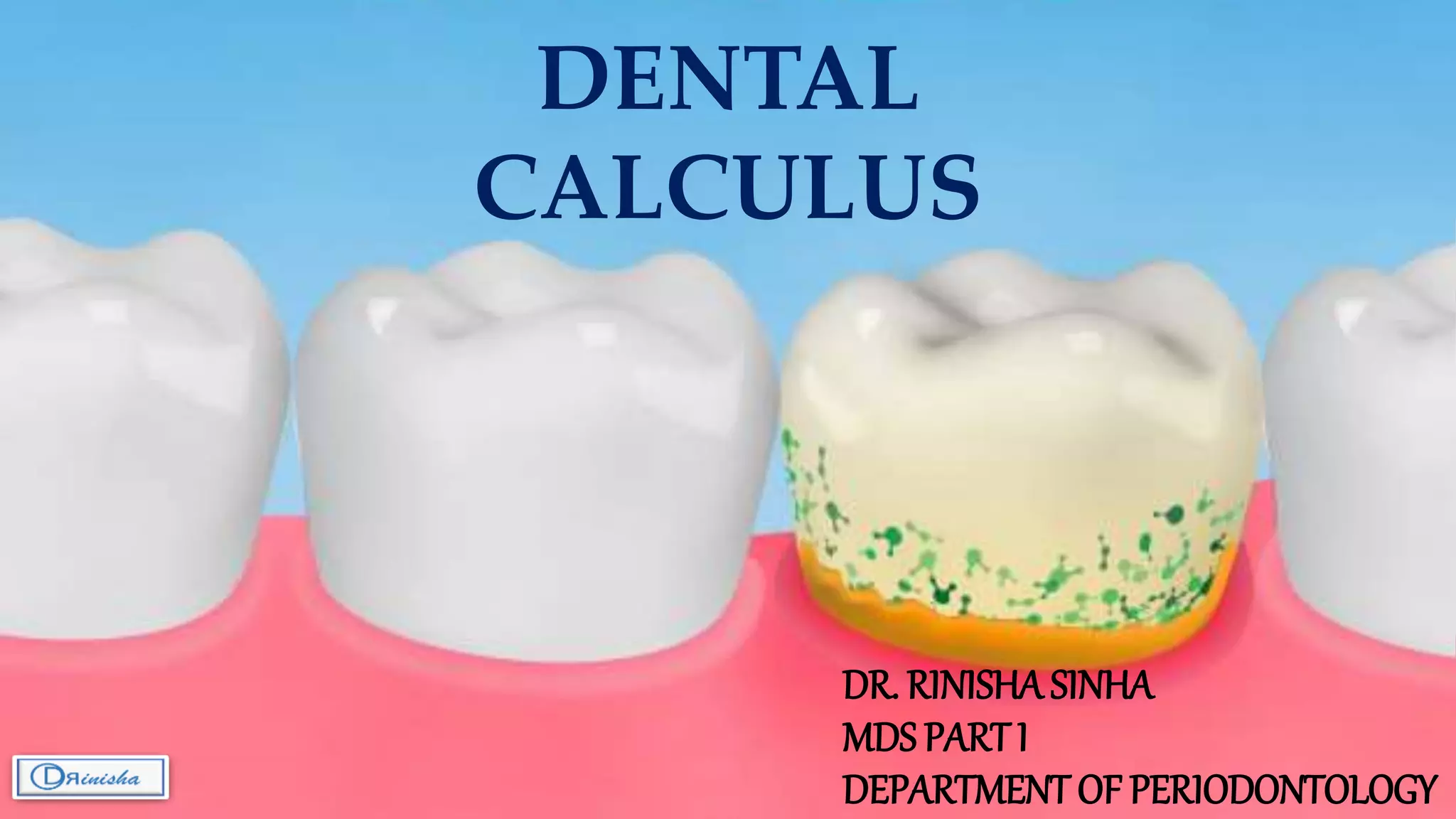

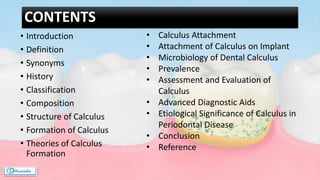

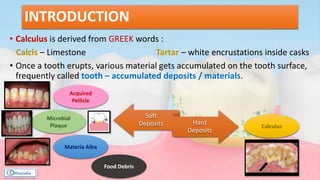

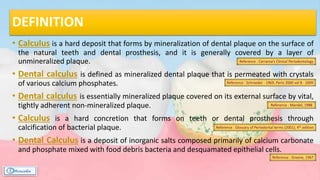

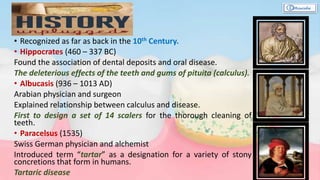

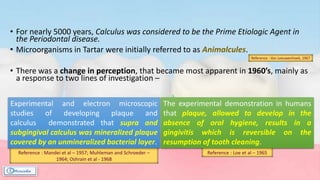

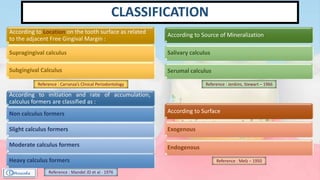

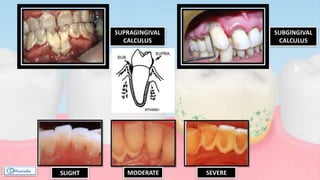

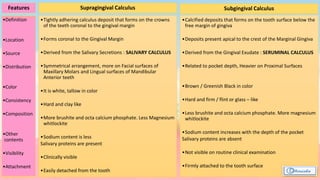

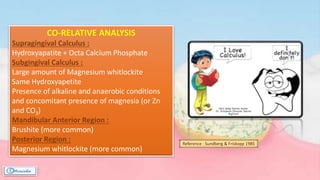

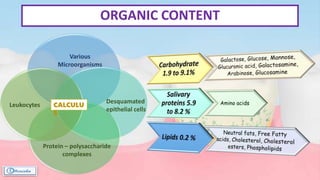

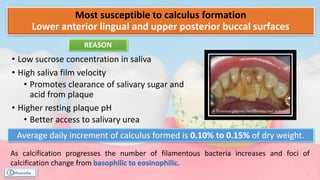

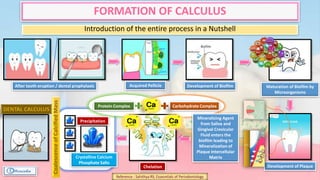

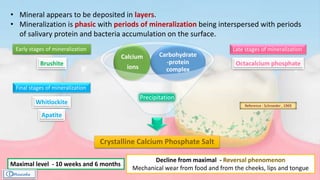

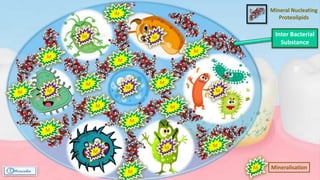

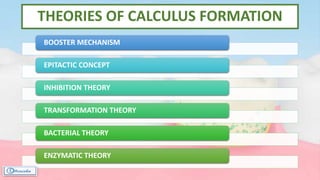

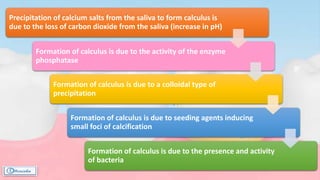

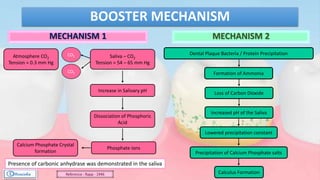

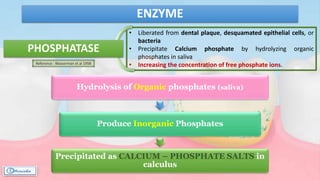

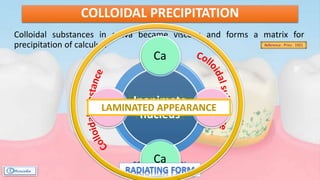

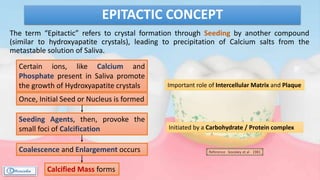

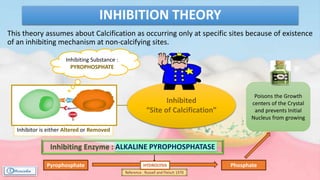

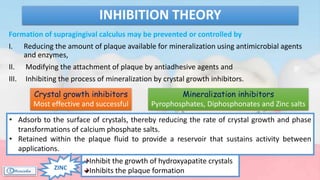

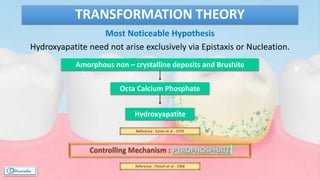

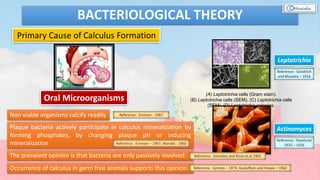

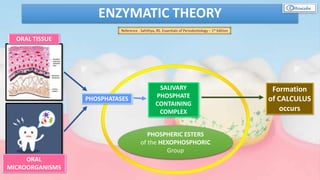

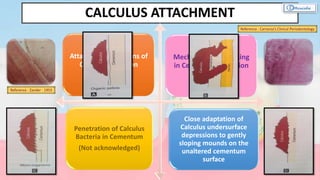

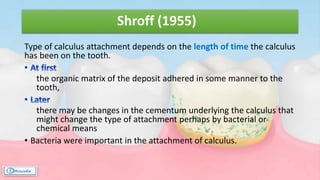

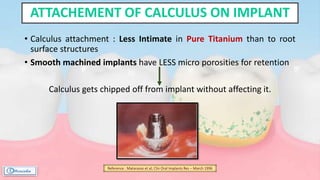

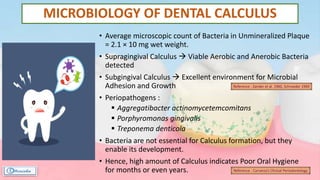

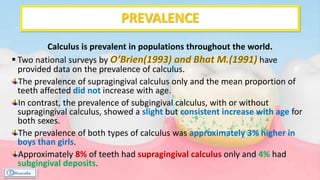

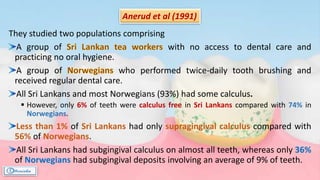

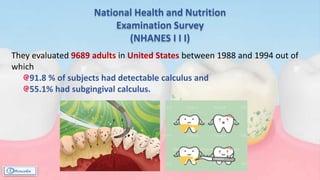

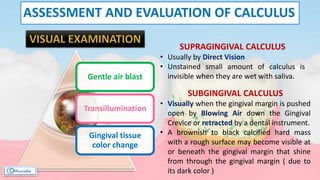

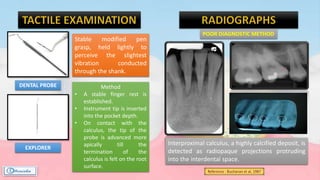

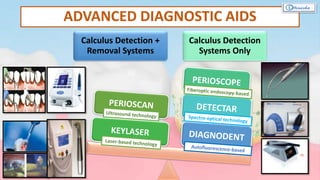

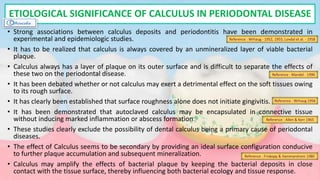

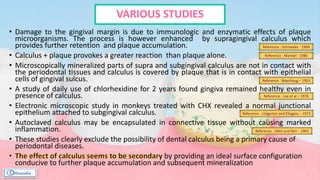

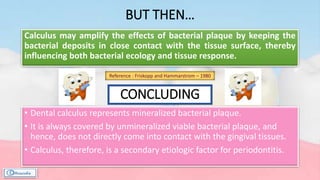

The document provides a comprehensive overview of dental calculus, including its definition as a mineralized plaque on teeth, classification based on various factors, and the complex process of its formation. It discusses historical perspectives on calculus, its microbial composition, and the pathological significance related to periodontal disease. The document also outlines diagnostic strategies and theories regarding the mechanisms of calculus formation and attachment.