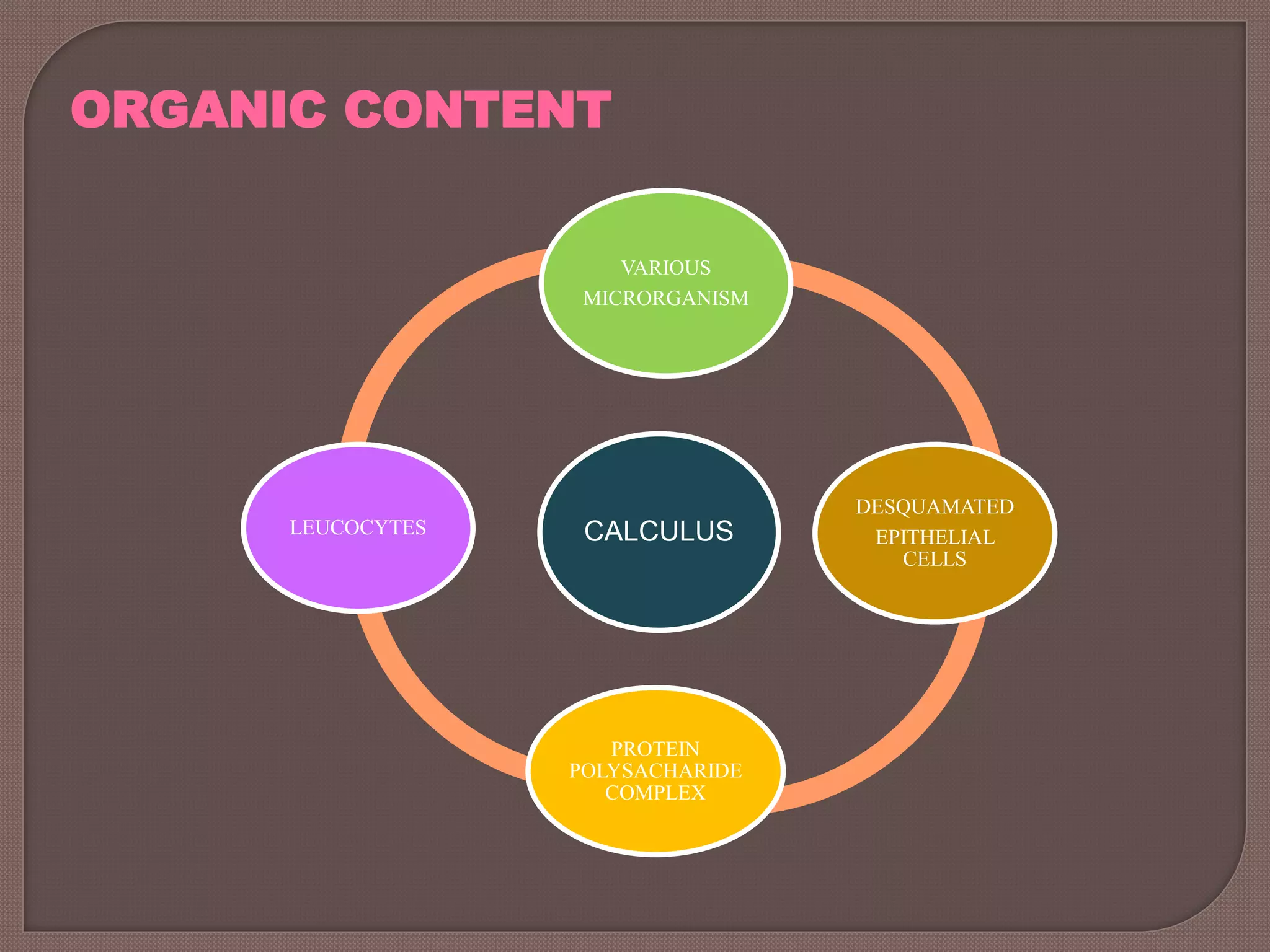

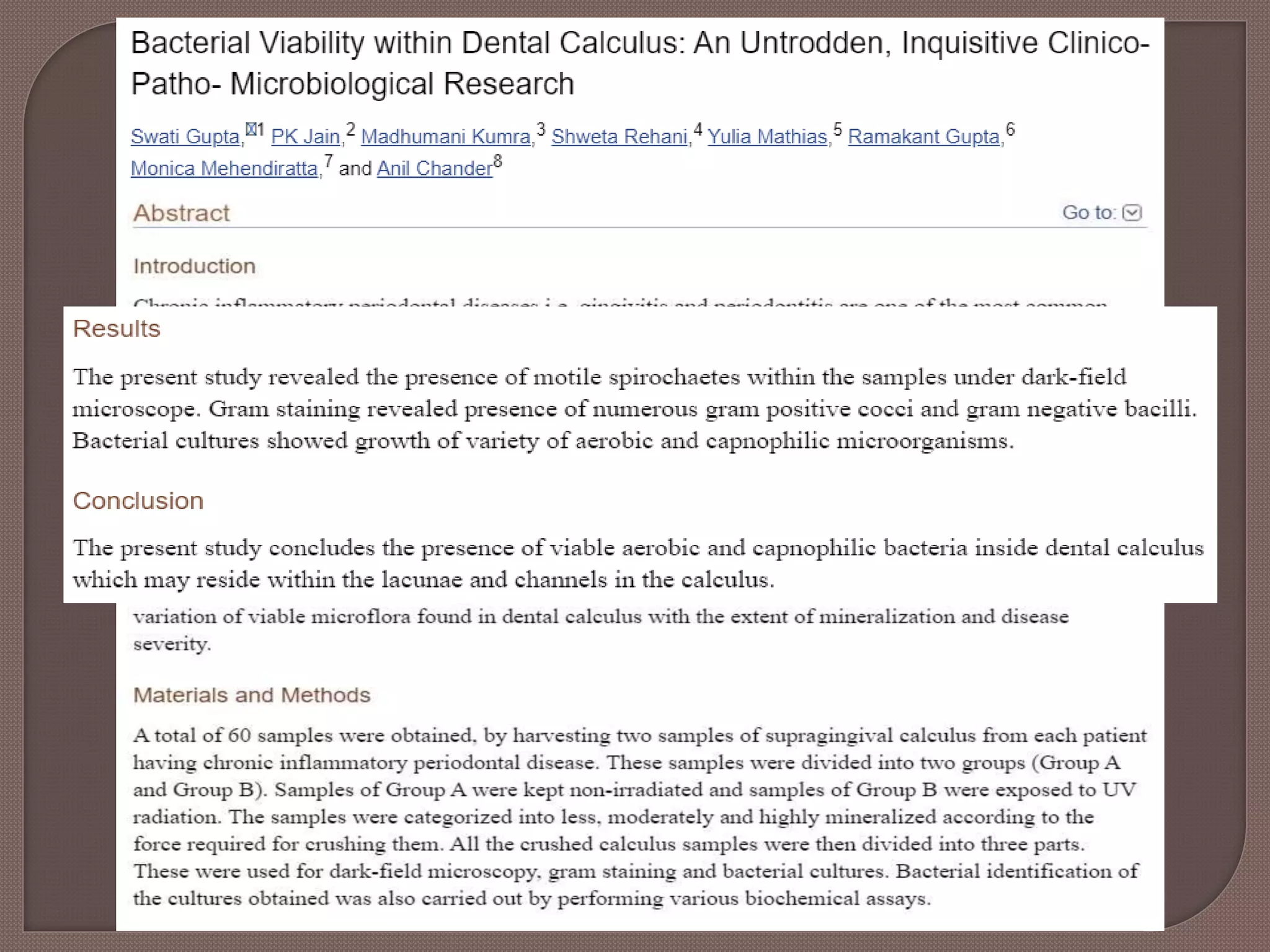

This document provides an overview of dental calculus, including its history, composition, formation, theories of mineralization, detection, and significance. It discusses the various components of calculus, both inorganic like calcium and organic like bacteria. Calculus forms through the mineralization of dental plaque on tooth surfaces over time. While calculus does not directly cause inflammation, it provides a surface for plaque to accumulate and remain close to gingiva. The document outlines several methods for detecting calculus, from visual inspection to newer technologies using optics, ultrasound, or lasers.

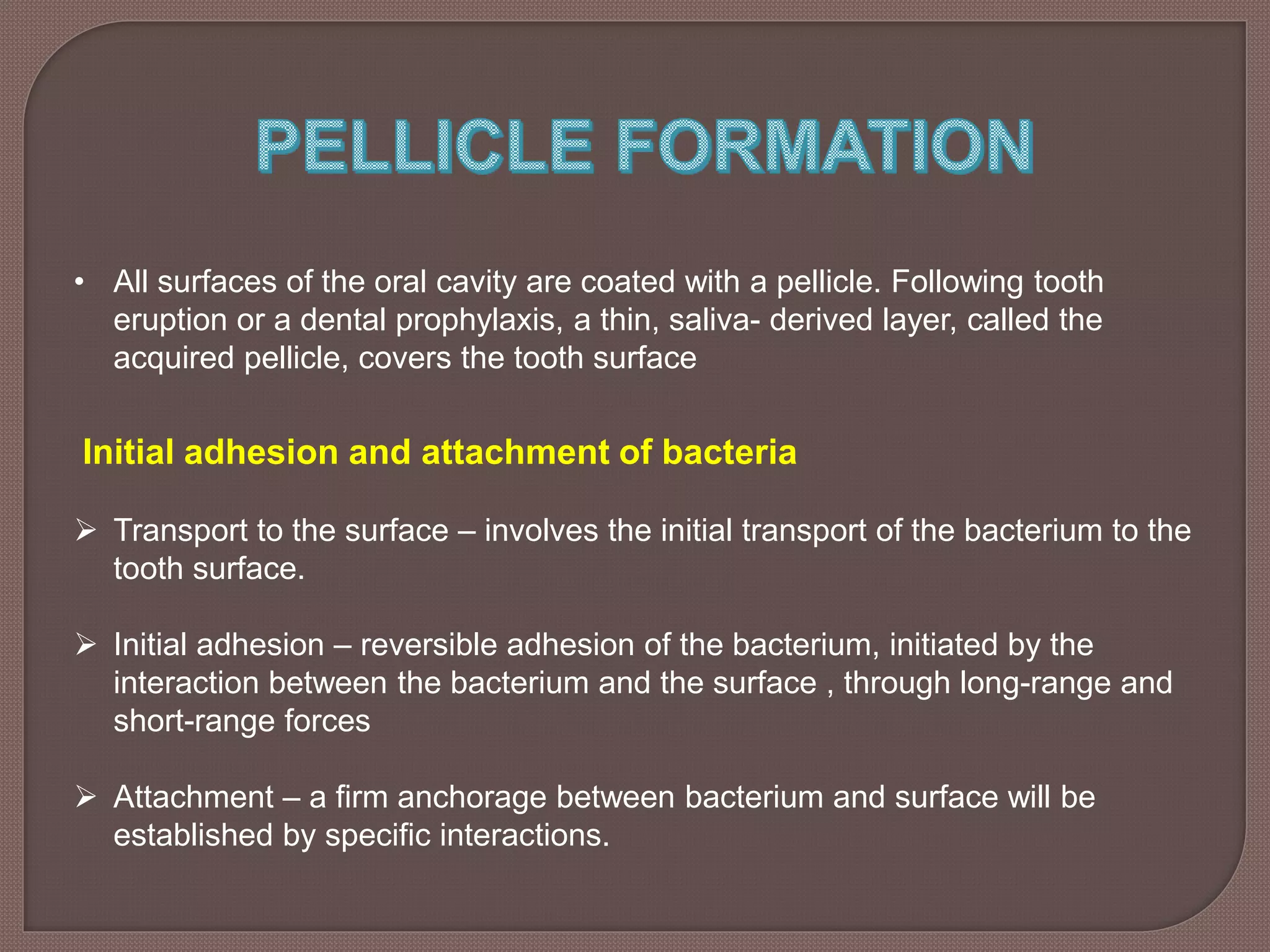

![Dental Calculus consists of mineralized bacterial plaque that forms on the

surfaces of natural teeth and dental prosthesis. [Carranza ]

A hard deposit that forms by mineralization of dental plaque and is generally

covered by a layer of unmineralized plaque (Lindhe)

A deposit of inorganic salts composed primarily of calcium carbonate and

phosphate mixed with food debris bacteria and desquamated epithelial cells.

(Greene 1967)

Calculus is derived from Greek words Calcis-lime stone, Tartar- white

encrustation inside casks.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/calculusppt-200512155055/75/Dental-Calculus-ppt-4-2048.jpg)