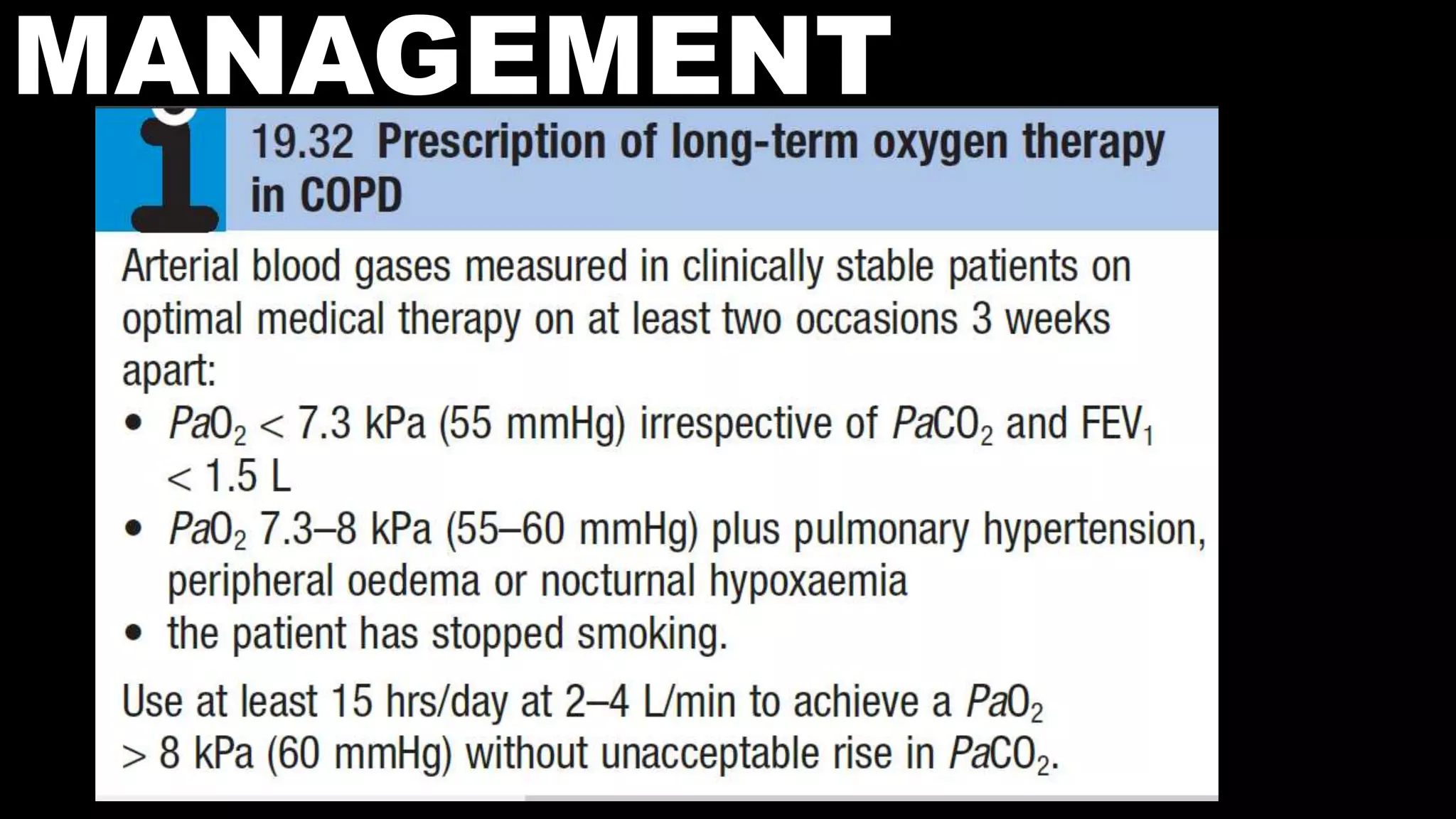

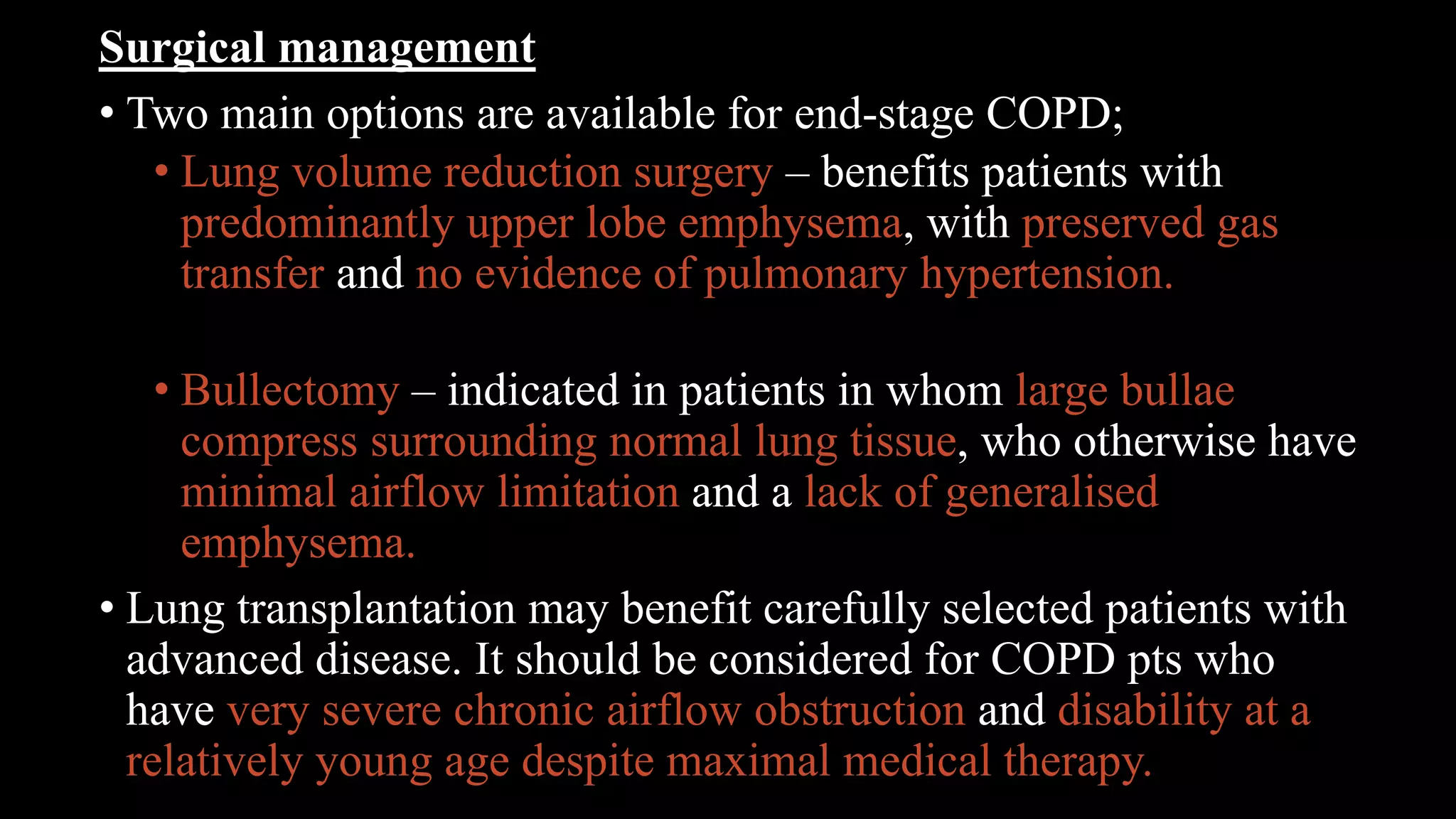

COPD is characterized by airflow limitation caused by chronic inflammation in the lungs. It affects over 80 million people worldwide and is predicted to become the third leading cause of death by 2020. The main risk factors are tobacco smoke and indoor air pollution. Symptoms include cough, sputum production and exertional dyspnea. Diagnosis involves lung function tests showing reduced FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio. Management focuses on smoking cessation and bronchodilators.