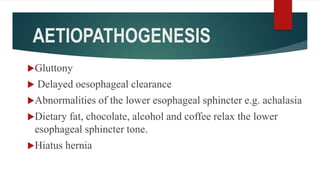

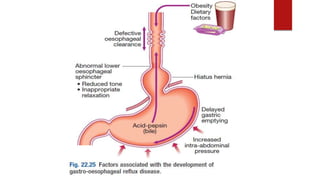

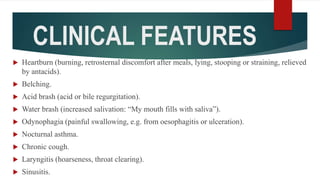

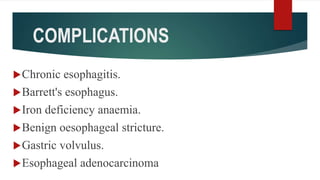

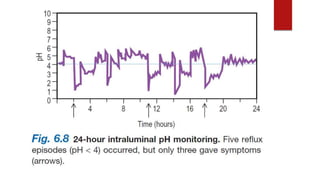

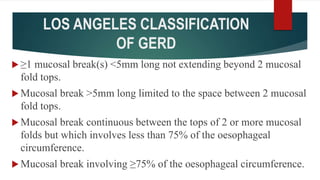

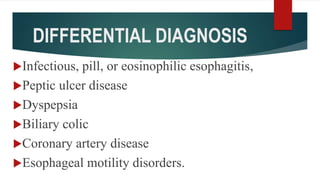

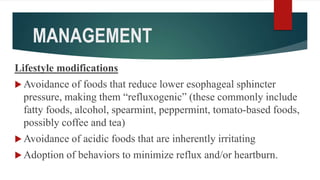

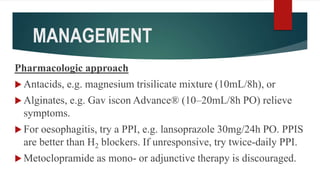

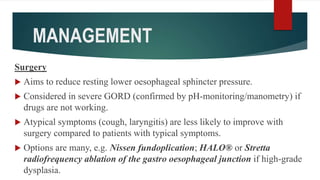

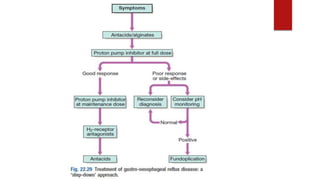

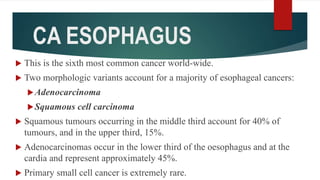

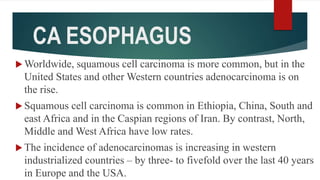

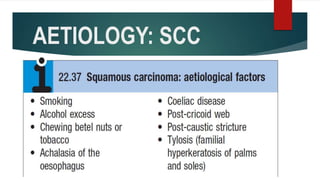

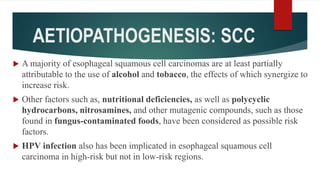

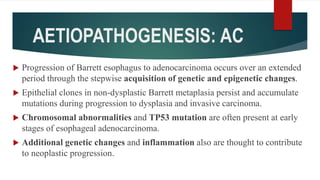

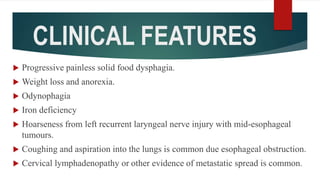

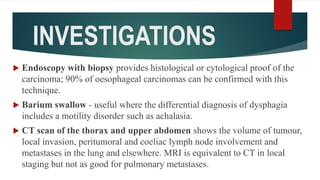

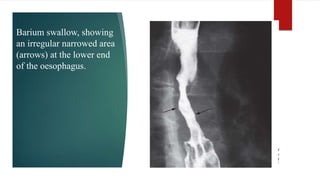

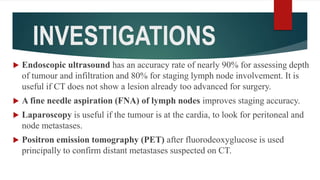

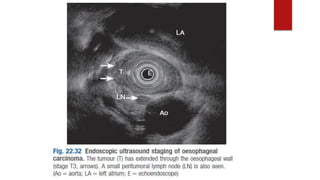

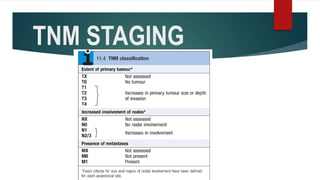

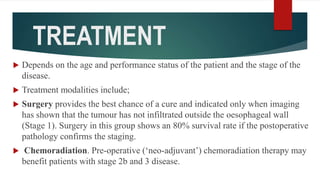

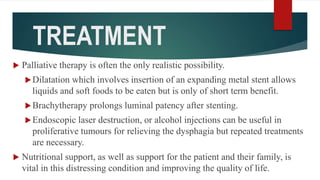

This document discusses GERD and esophageal cancer. It begins by defining GERD and describing its causes, including transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and hiatal hernias. It then covers the clinical features, investigations, and management of GERD, including lifestyle modifications, medications, and surgery. The document also discusses the two main types of esophageal cancer - squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma - including their risk factors, clinical features, staging, and treatment options.