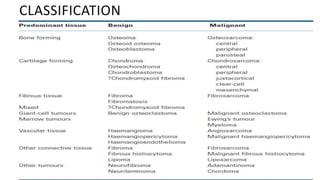

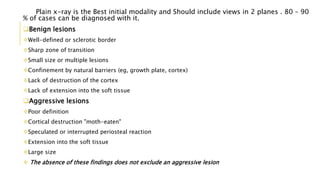

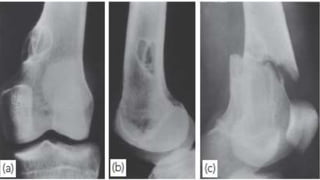

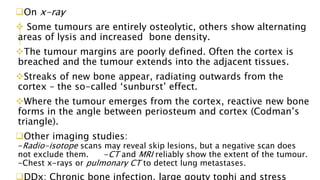

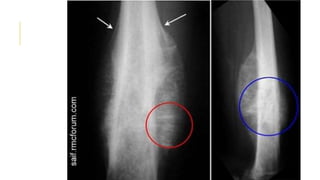

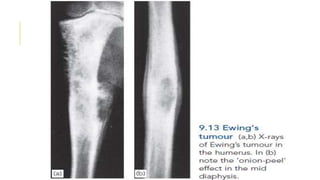

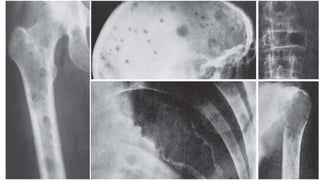

The document details common bone tumors, outlining their classifications, characteristics, imaging findings, and treatment options. It distinguishes between benign and aggressive lesions, describes specific tumors like non-ossifying fibroma, osteoid osteoma, and osteosarcoma, and highlights metastatic bone disease and multiple myeloma as serious conditions. The document emphasizes the importance of diagnostic imaging for accurate diagnosis and management of these bone tumors.