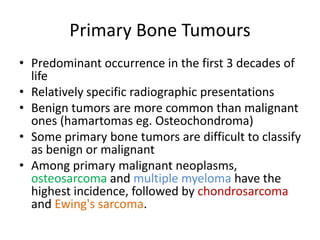

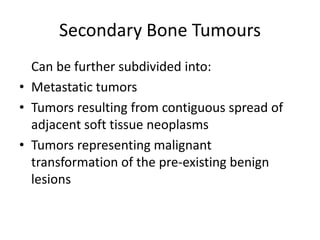

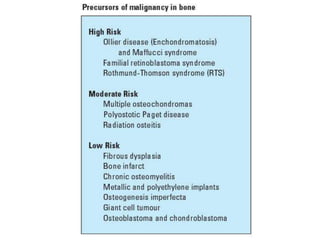

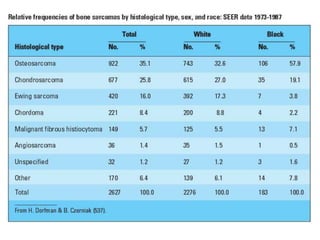

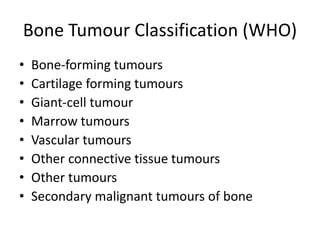

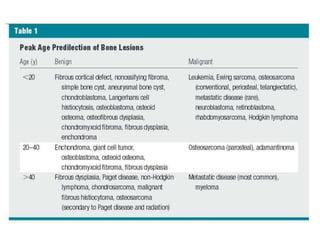

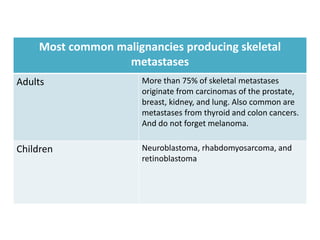

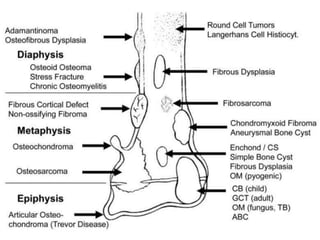

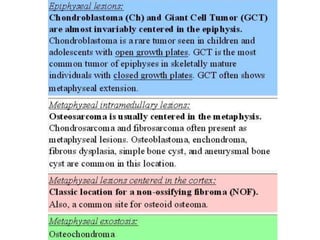

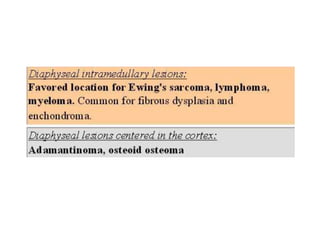

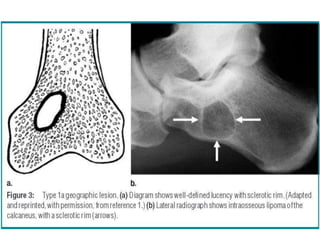

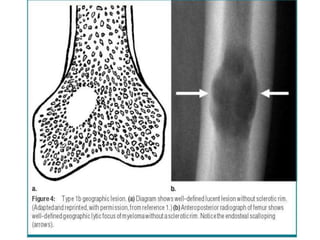

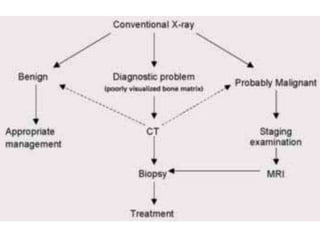

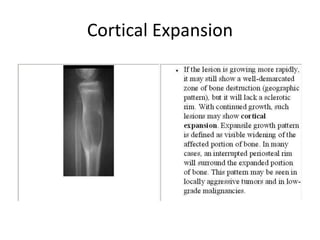

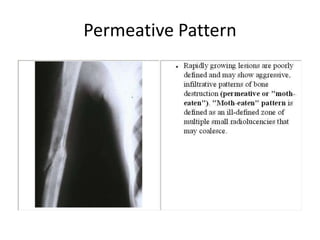

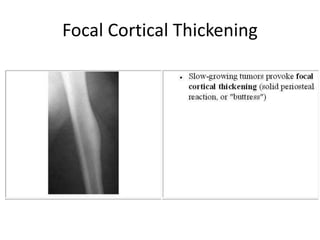

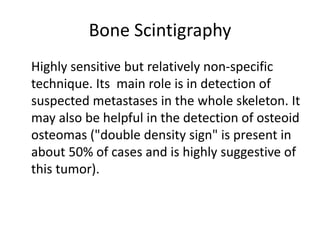

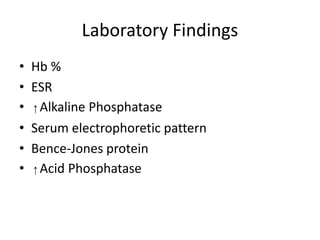

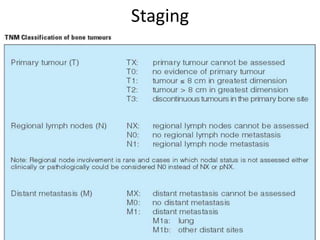

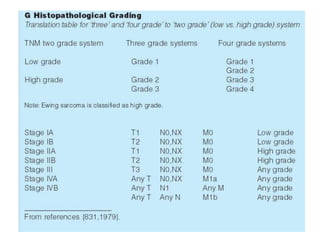

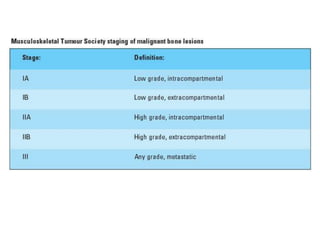

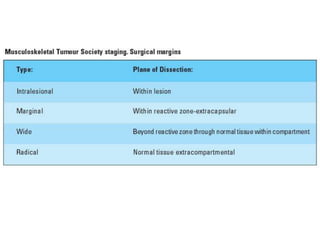

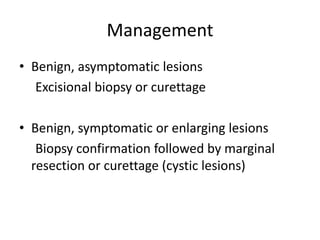

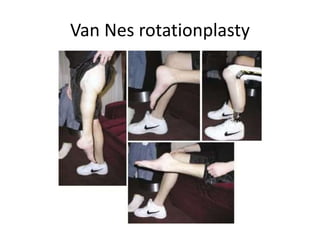

This document discusses bone tumors. It defines bone tumors and divides them into primary and secondary tumors. Primary bone tumors are rare, accounting for 0.2% of adult and 5% of childhood cancers. The document describes the typical characteristics, locations, and most common types of both primary bone tumors and secondary bone metastases. It outlines the clinical features, diagnostic imaging, laboratory investigations, biopsy, staging, and management of bone tumors.