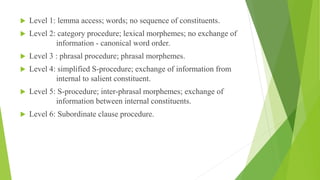

The document discusses cognitive approaches to second language learning, contrasting them with behaviorism, emphasizing that language acquisition involves conscious processing and learning strategies. It outlines various schools of thought, key cognitive theorists, and specific models, such as information processing and processability theory, to explain how learners acquire language and restructure their knowledge. The document also explores learning strategies that enhance language acquisition, focusing on metacognitive, cognitive, and social/affective approaches.