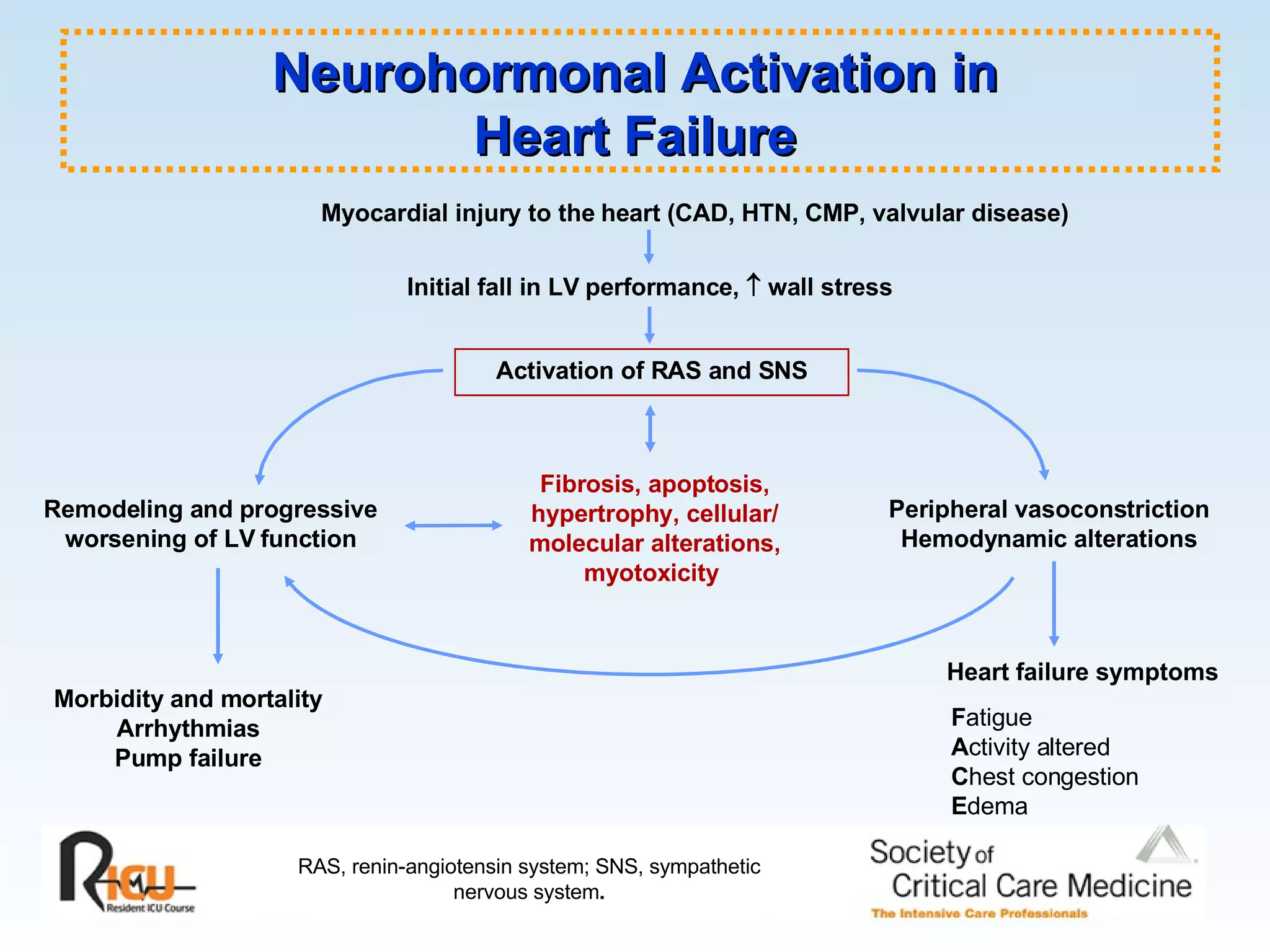

The document discusses cardiogenic shock, which results from inadequate tissue perfusion due to cardiac dysfunction. Cardiogenic shock is defined by a sustained systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg, cardiac index below 2.2 L/min/m2, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure above 15 mm Hg. Causes of cardiogenic shock include acute myocardial infarction, mechanical complications, right ventricular infarction, and other conditions such as cardiomyopathy. The pathophysiology and management of cardiogenic shock are discussed.