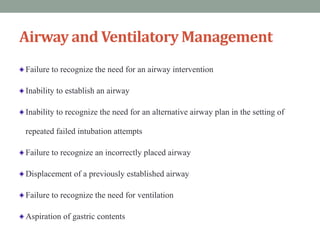

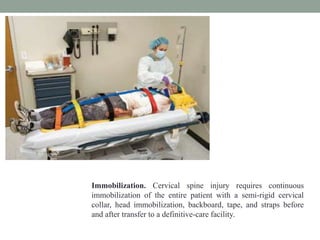

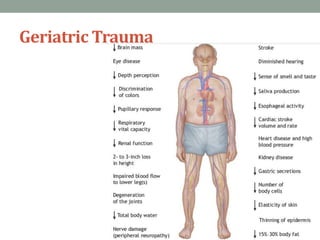

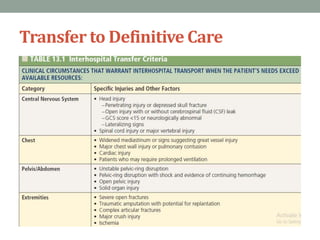

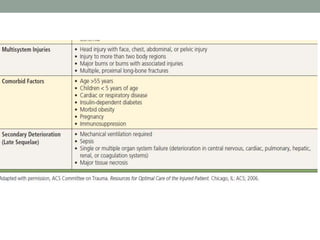

This document outlines Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. It covers the initial assessment and management of trauma patients, including the primary and secondary surveys, as well as specific treatments for injuries like airway management, shock, head trauma, spinal trauma, thoracic trauma, abdominal trauma, burns, pediatric trauma, and geriatric trauma. It emphasizes the need for a systematic approach to rapidly triage and stabilize injured patients before transferring them to definitive care facilities.

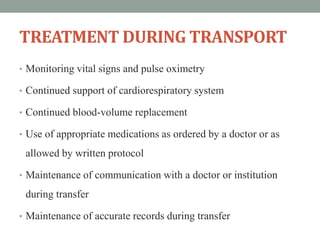

![TREATMENT PRIOR TO TRANSFER

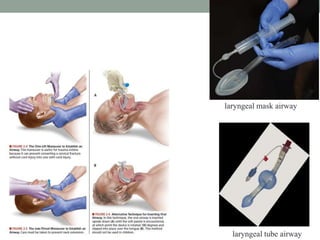

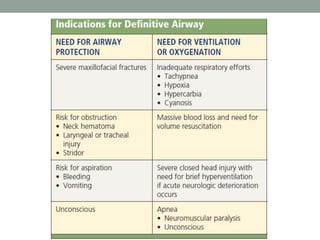

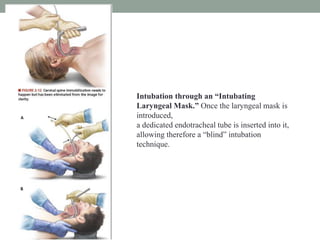

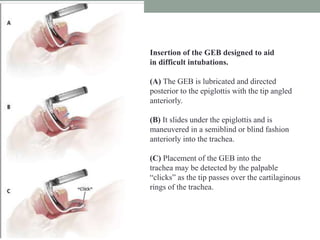

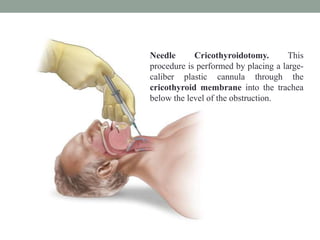

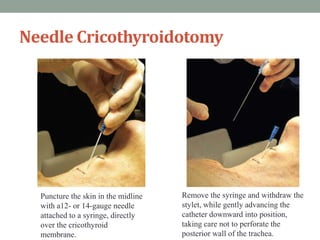

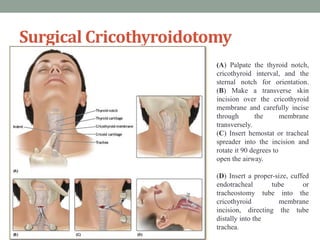

1. Airway

a. Insert an airway or endotracheal tube, if needed.

b. Provide suction.

c. Insert a gastric tube to reduce the risk of aspiration.

2. Breathing

a. Determine rate and administer supplementary oxygen.

b. Provide mechanical ventilation when needed.

c. Insert a chest tube if needed.

3. Circulation

a. Control external bleeding.

b. Establish two large-caliber intravenous lines

and begin crystalloid solution infusion.

c. Restore blood volume losses with crystalloid fluids or blood and

continue replacement during transfer.

d. Insert an indwelling catheter to monitor urinary output.

e. Monitor the patient’s cardiac rhythm and rate.

4. Central nervous system

a. Assist respiration in unconscious patients.

b. Administer mannitol, if needed.

c. Immobilize any head, neck, thoracic, and lumbar

spine injuries.

5. Diagnostic studies (When indicated; obtaining these

studies should not delay transfer.)

a. Obtain x-rays of chest, pelvis, and extremities.

b. Sophisticated diagnostic studies, such as CT and aortography,

are usually not indicated.

c. Order hemoglobin or hematocrit, type and crossmatch, and

arterial blood gas determinations for all patients; also order

pregnancy tests for females of childbearing age.

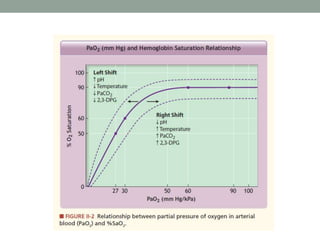

d. Determine cardiac rhythm and hemoglobin saturation

(electrocardiograph [ECG] and pulse oximetry).

6. Wounds (Performing these procedures should not delay

transfer.)

a. Clean and dress wounds after controlling external

hemorrhage.

b. Administer tetanus prophylaxis.

c. Administer antibiotics, when indicated.

7. Fractures

a. Apply appropriate splinting and traction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atls-170117171058/85/advanced-trauma-life-support-59-320.jpg)