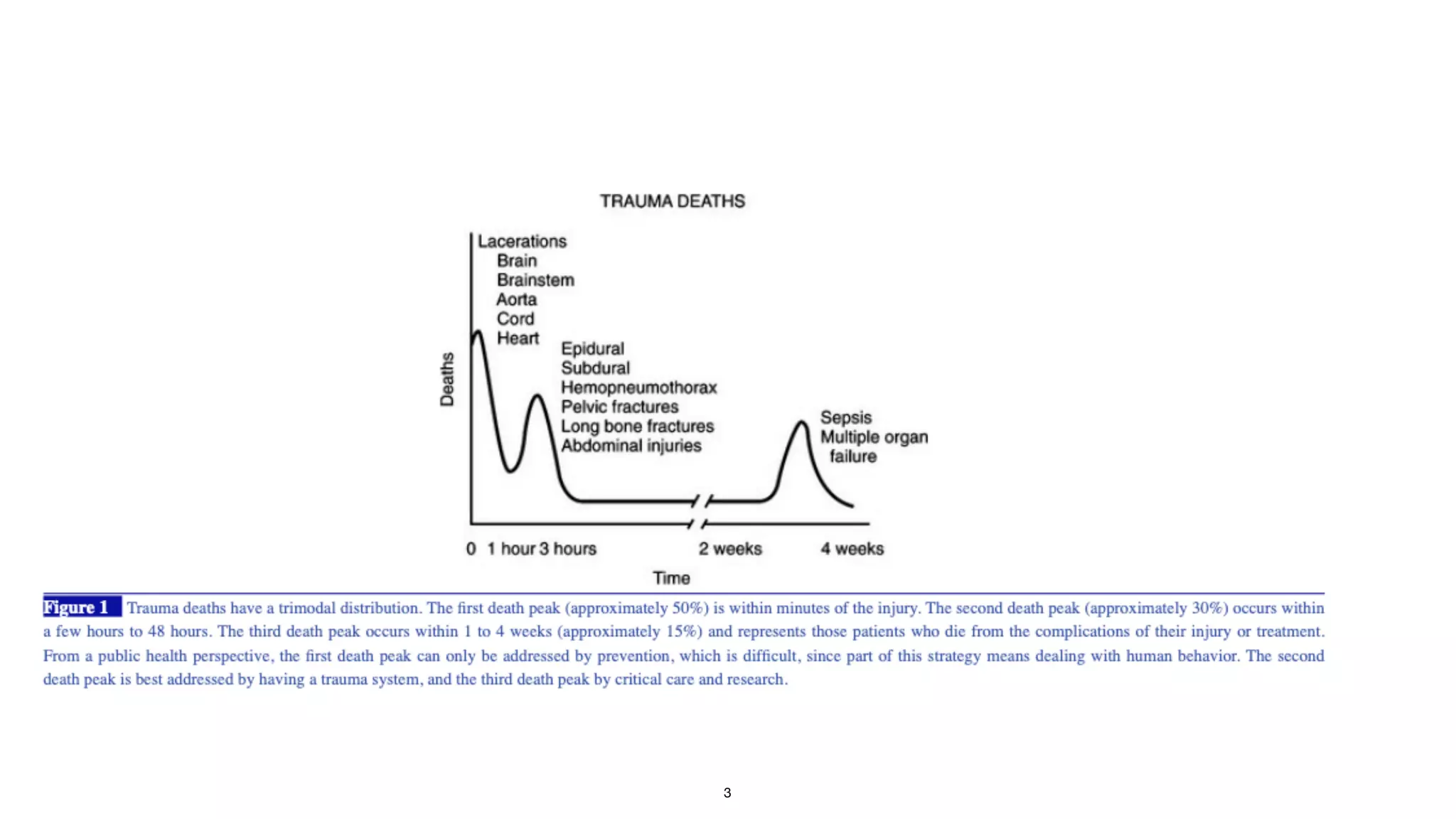

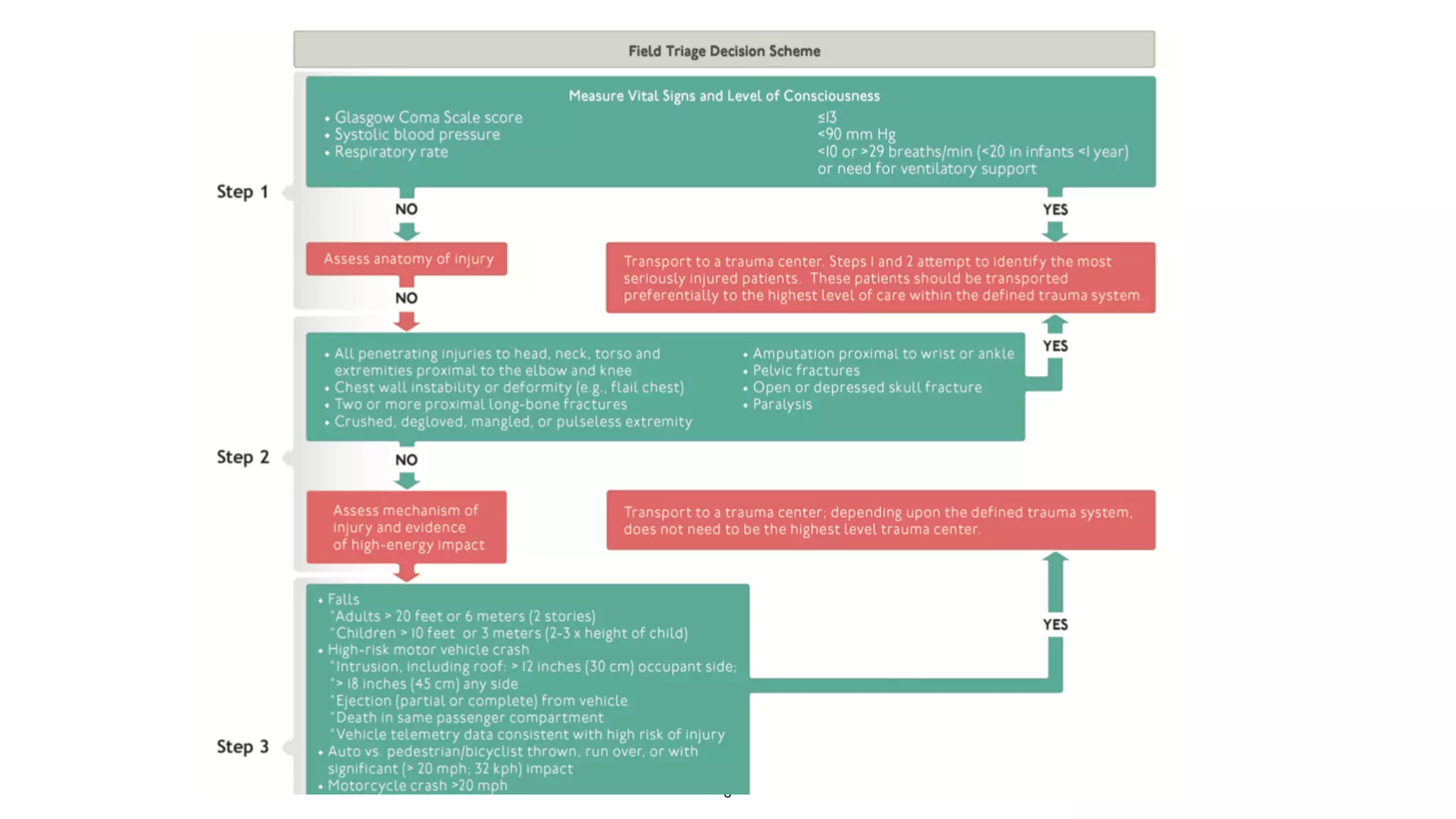

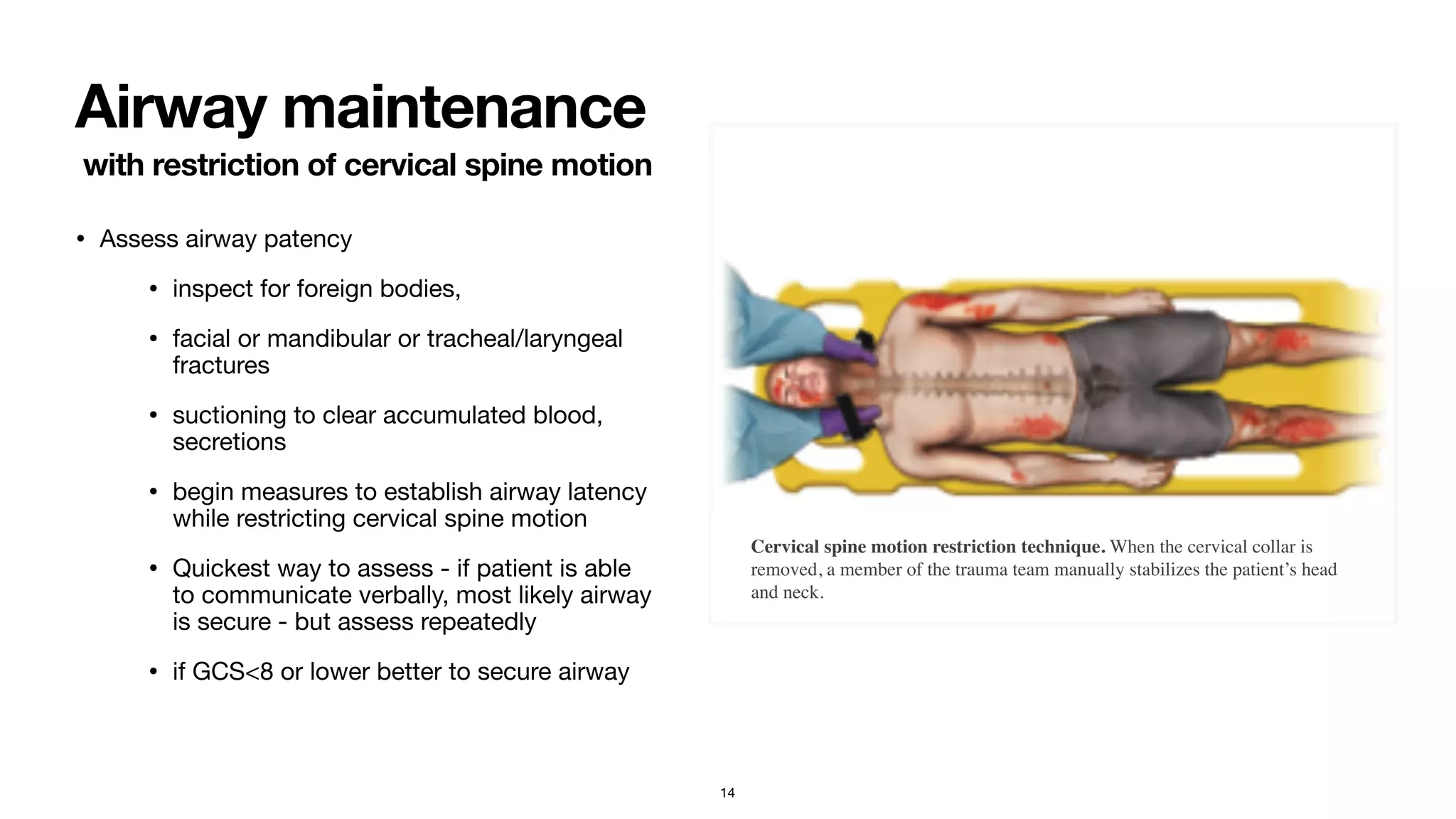

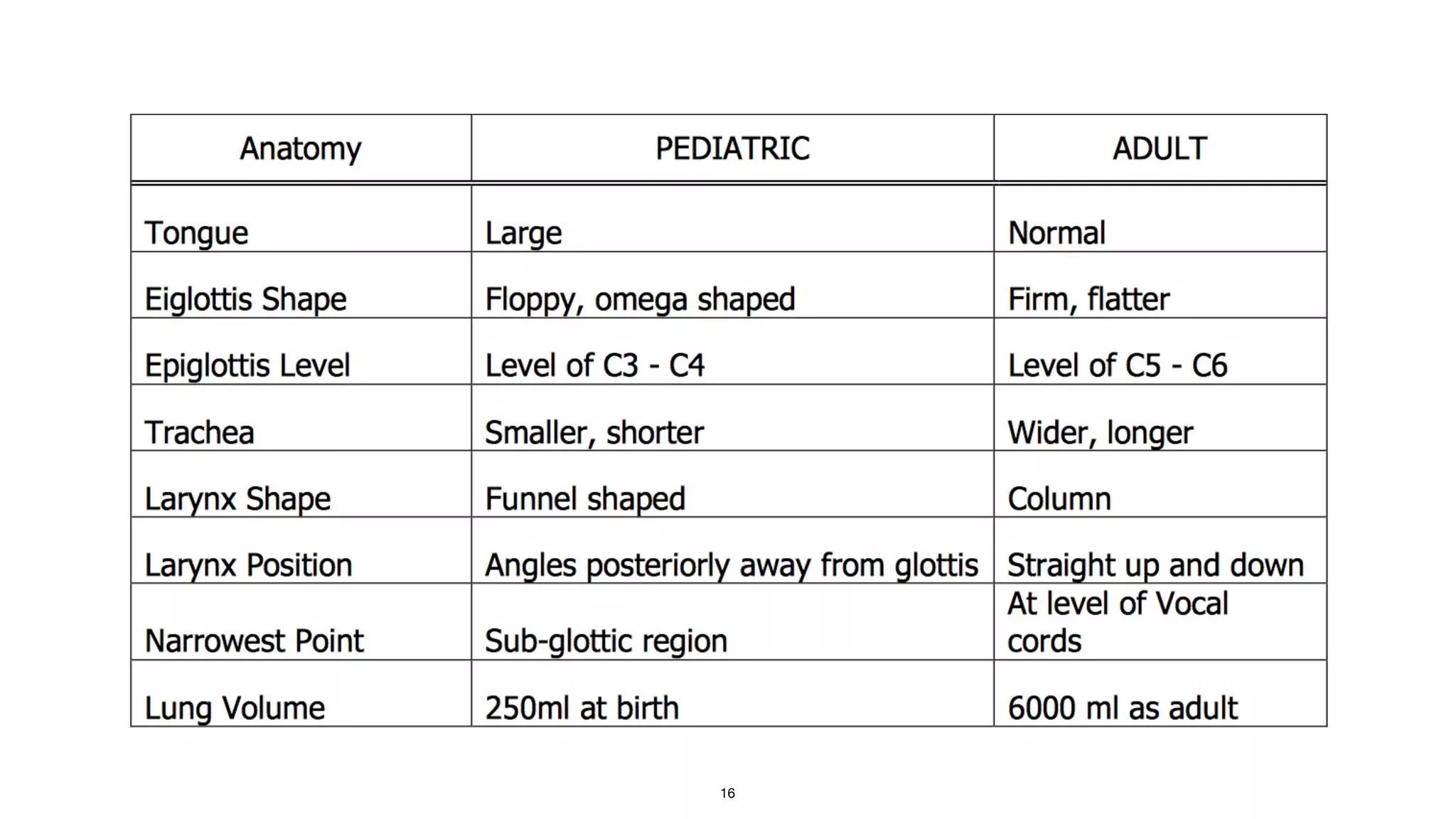

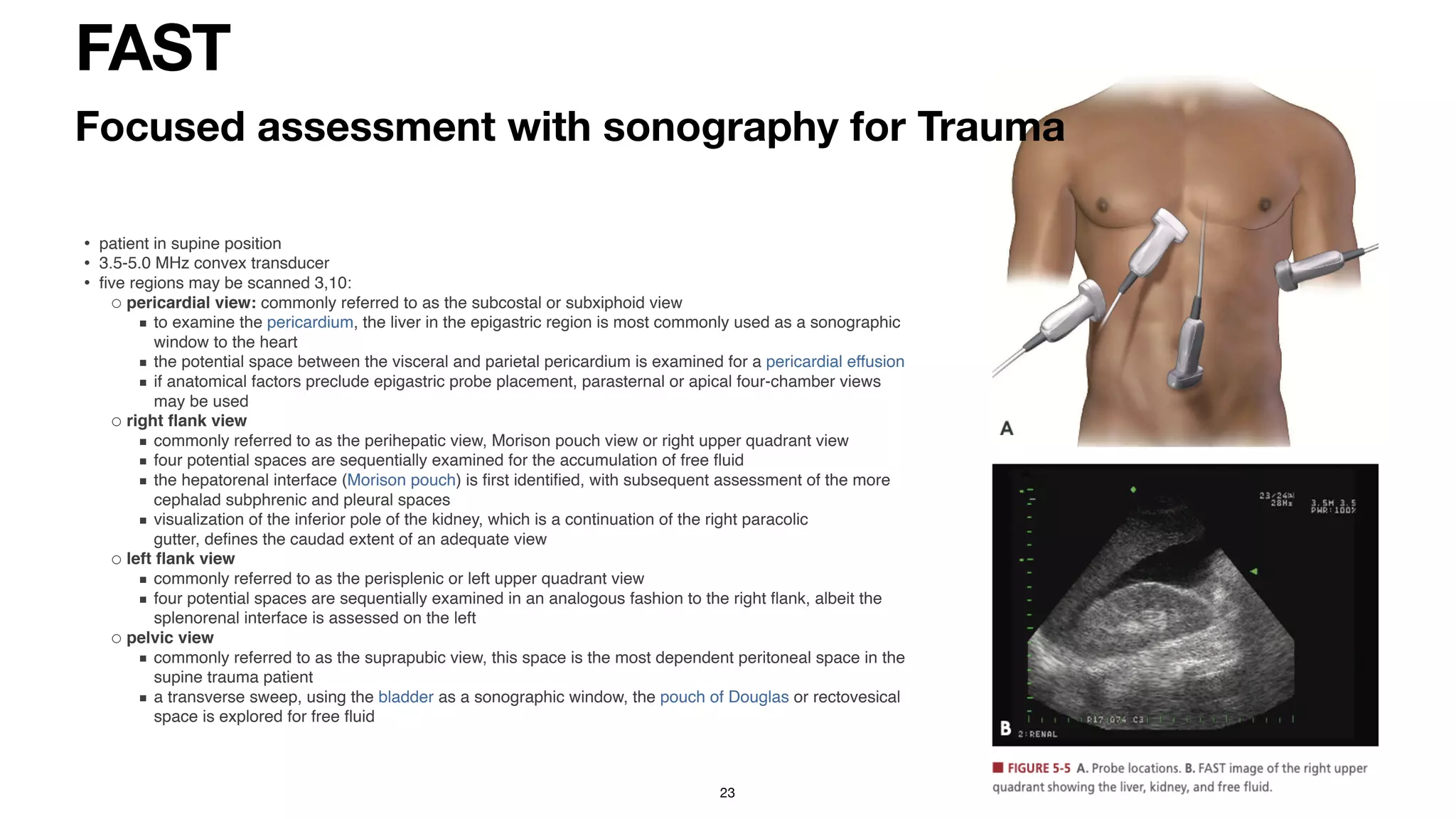

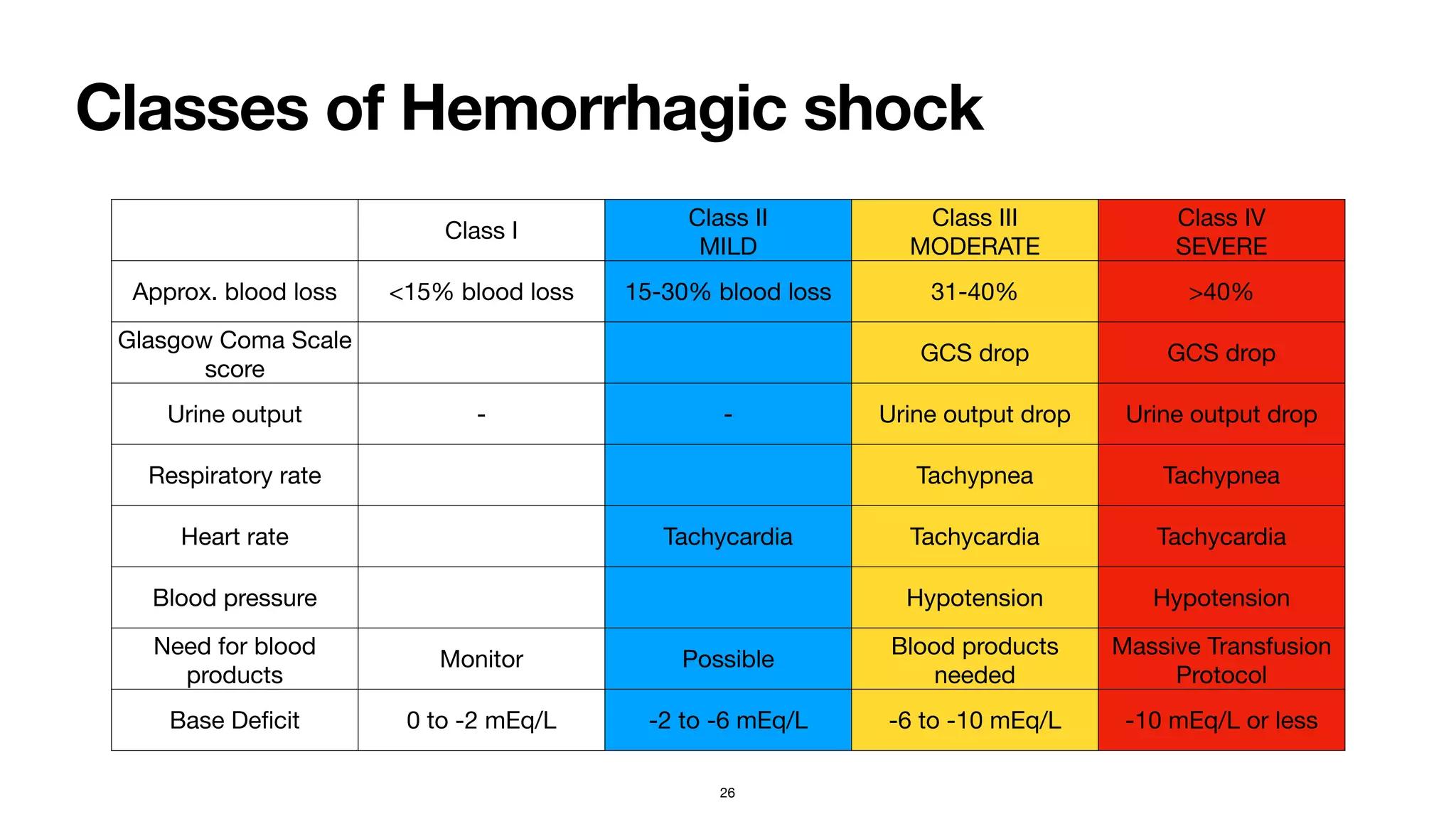

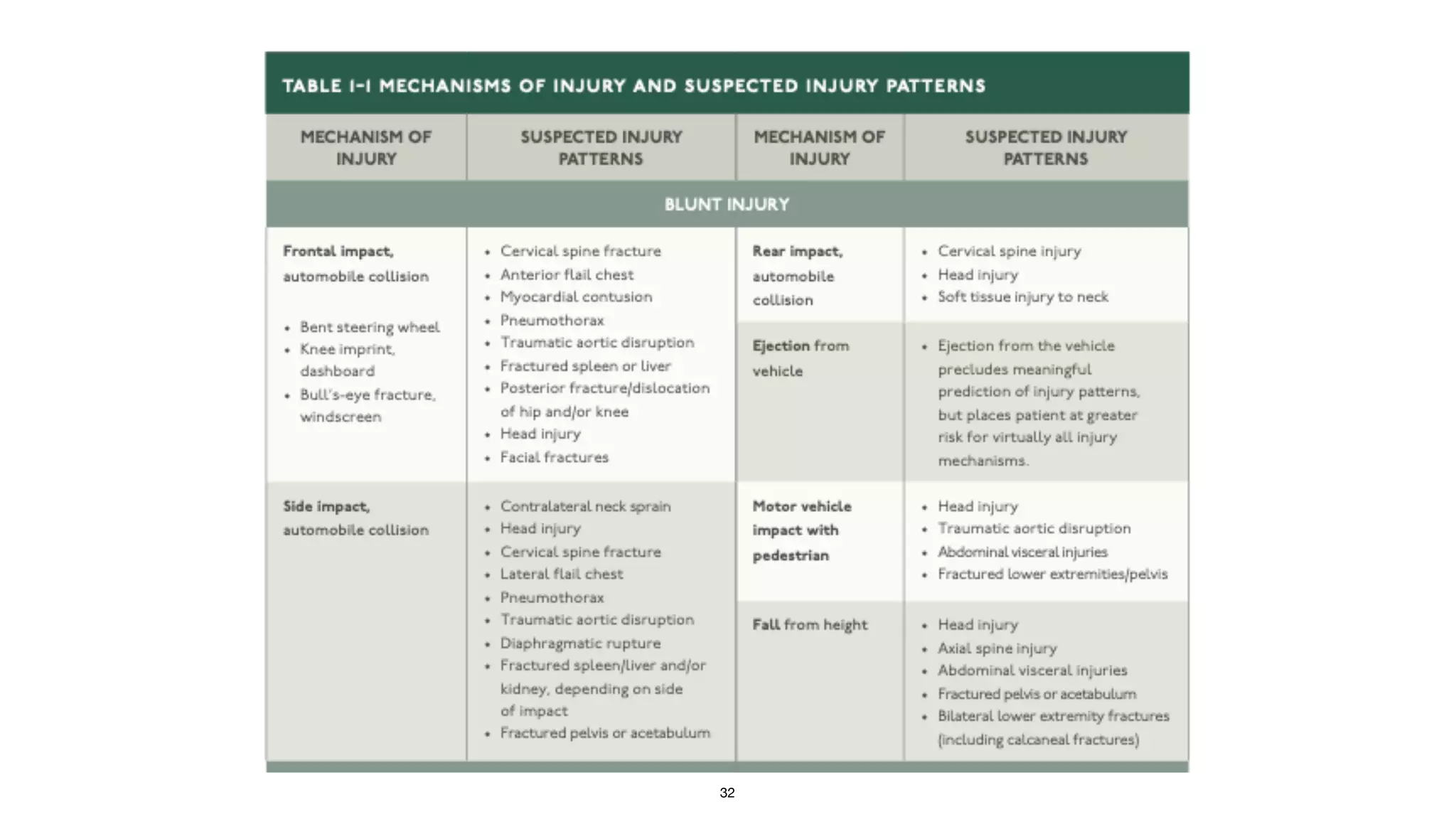

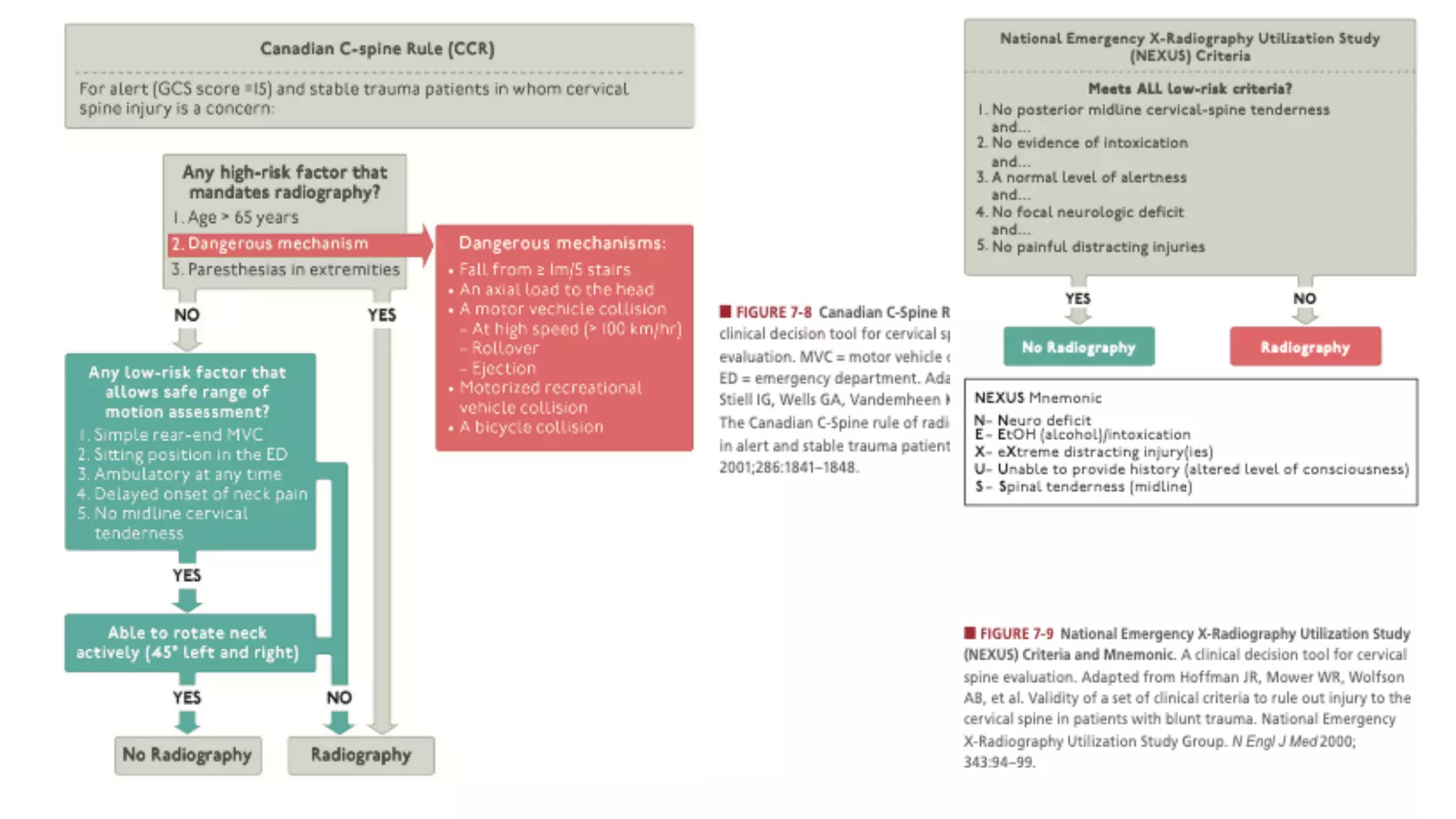

The document provides information on the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) approach to evaluating and managing trauma patients. It discusses the history and concepts of ATLS, including focusing first on treating life-threatening injuries in the order of airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure (ABCDE). The summary describes the primary and secondary surveys in ATLS for initial assessment and management of trauma patients. It also highlights key components such as hemorrhage control, use of the FAST exam, and damage control resuscitation principles.