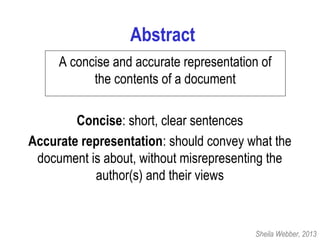

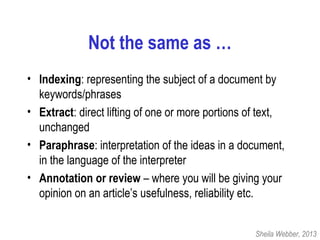

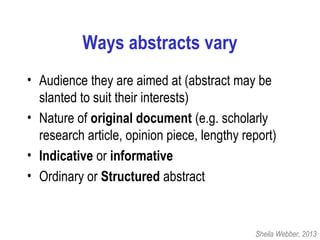

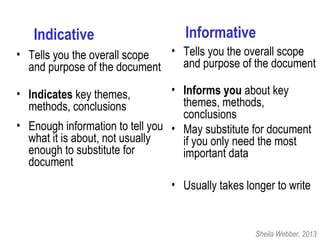

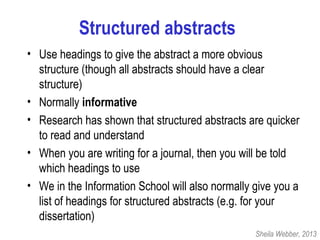

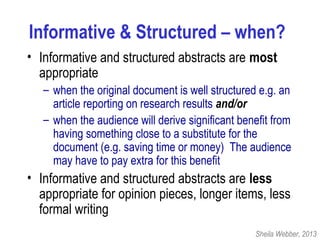

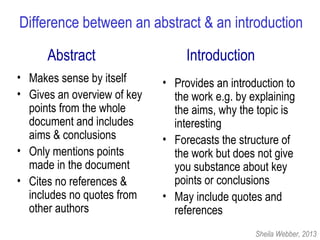

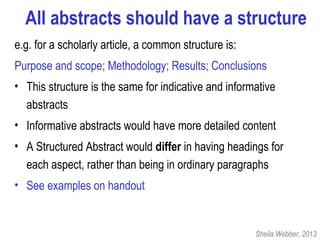

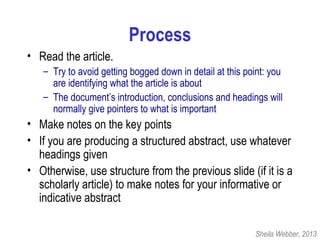

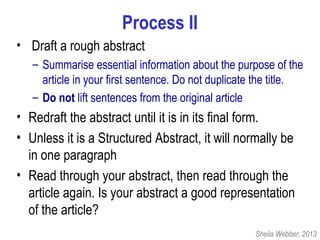

The document discusses the significance and characteristics of abstracts, emphasizing their role in summarizing the content of a document clearly and concisely. It distinguishes between various types of abstracts, including indicative, informative, and structured forms, and outlines the appropriate contexts for their use. Additionally, it provides guidance on writing effective abstracts and the evaluation process to ensure they accurately represent the source material.