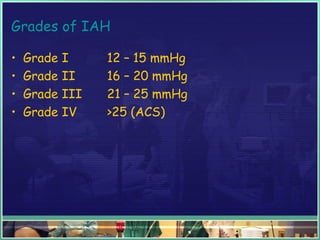

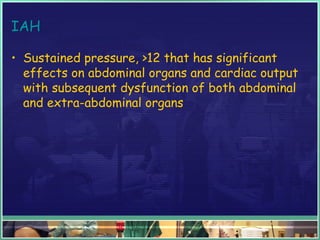

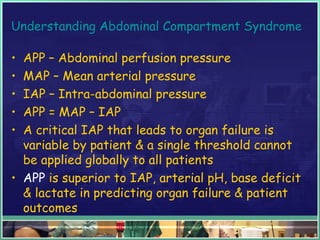

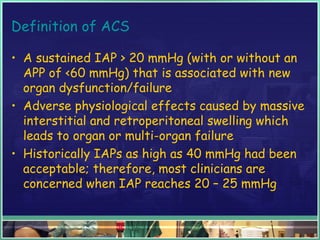

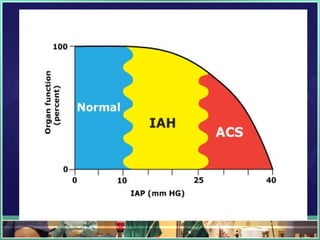

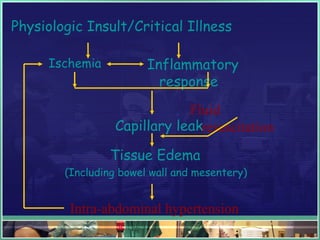

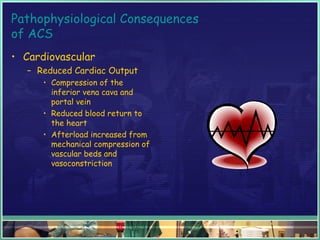

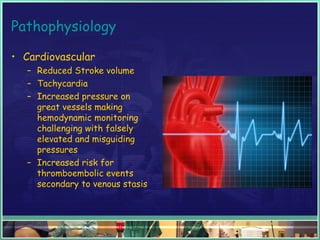

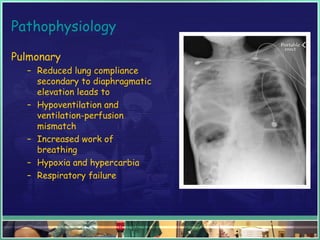

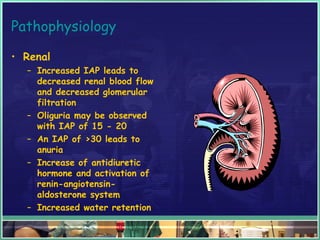

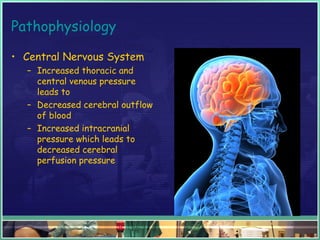

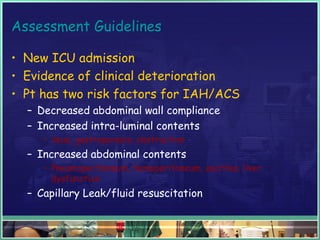

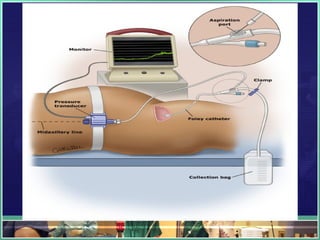

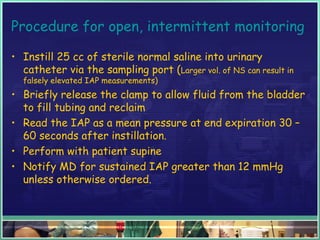

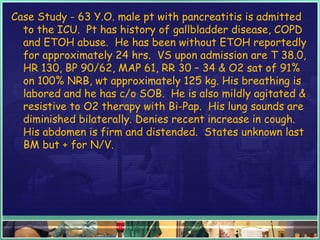

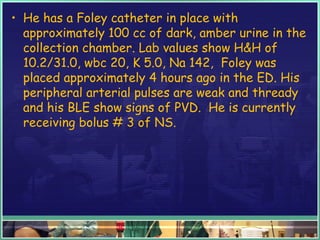

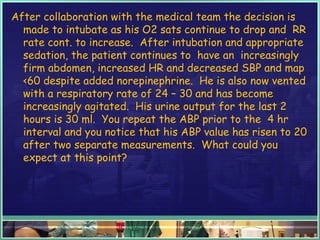

This document discusses abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). It defines ACS as a sustained intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) above 20 mmHg associated with new organ dysfunction. Normal IAP is 5-7 mmHg. Intra-abdominal hypertension is defined as IAP above 12 mmHg and is graded. ACS can result from primary abdominal causes or secondary extra-abdominal causes and leads to organ dysfunction through reduced blood flow. Accurate IAP monitoring via bladder pressure is important for early detection and treatment to prevent organ failure.