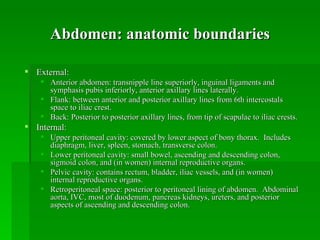

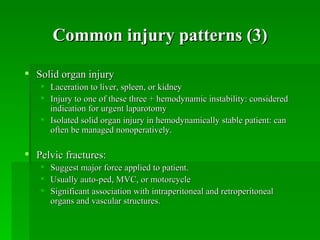

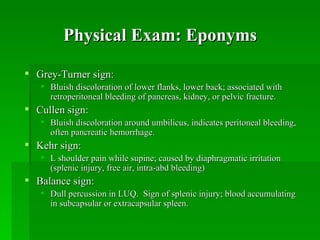

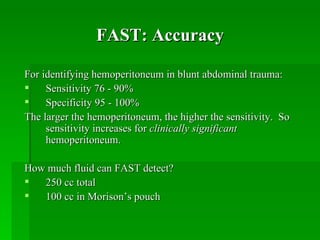

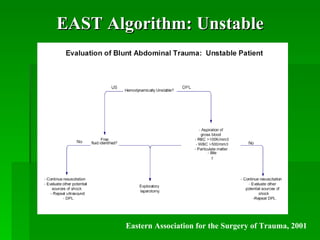

This document summarizes evaluation and management of blunt abdominal trauma. It defines the abdominal anatomy, describes common injury patterns from compression or deceleration mechanisms. The assessment involves history of the traumatic mechanism and physical exam findings. Diagnostic tools discussed include peritoneal lavage, FAST ultrasound, and CT scan. Algorithms are provided for management of hemodynamically unstable versus stable patients based on EAST guidelines.