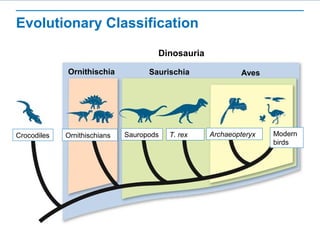

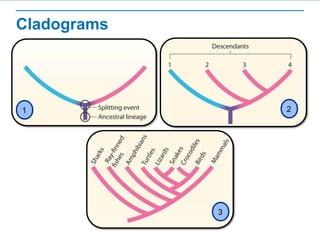

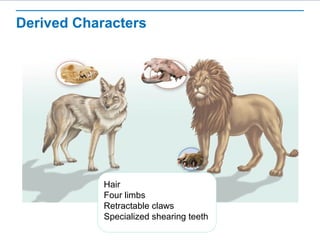

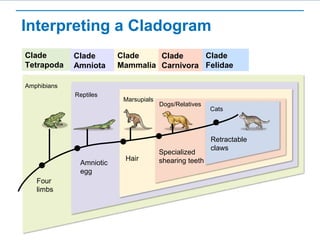

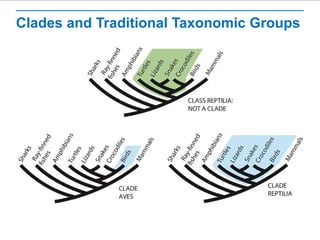

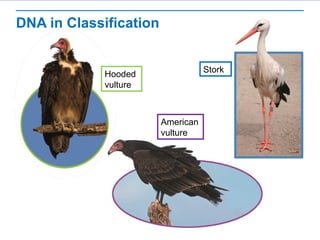

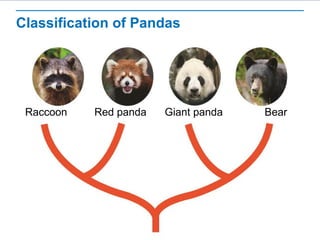

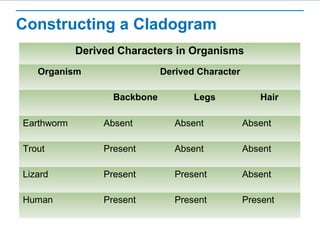

This document discusses modern evolutionary classification and how it differs from Linnaean classification. It explains how to make and interpret cladograms using shared derived characters to show evolutionary relationships between organisms. DNA sequences are also used in classification. Cladograms place organisms in clades based on shared ancestors and can be used to classify organisms differently than traditional taxonomic groups. Constructing cladograms involves identifying derived characters in organisms.