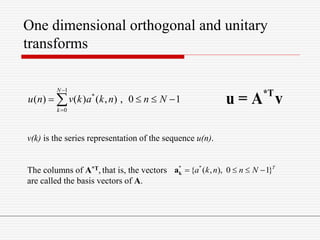

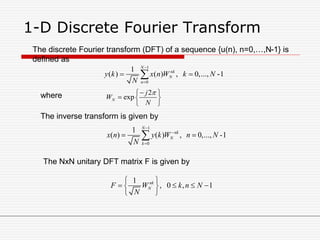

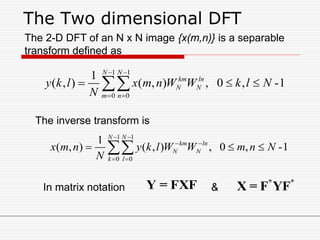

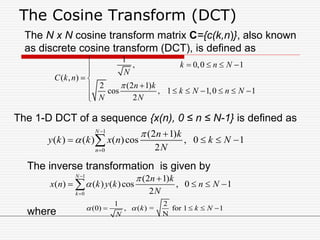

The document discusses various image transforms. It begins by explaining why transforms are used, such as for fast computation and obtaining conceptual insights. It then introduces image transforms as unitary matrices that represent images using a discrete set of basis images. It proceeds to describe one-dimensional orthogonal and unitary transforms using matrices. It also discusses separable two-dimensional transforms and provides properties of unitary transforms such as energy conservation. Specific transforms discussed in more detail include the discrete Fourier transform, discrete cosine transform, discrete sine transform, and Hadamard transform.

![Properties of Unitary Transforms

Energy compaction

Unitary transforms pack a large fraction of the

average energy of the image into a relatively

few components of the transform coefficients.

i.e. many of the transform coefficients contain

very little energy.

Decorrelation

When the input vector elements are highly

correlated, the transform coefficients tend to be

uncorrelated.

Covariance matrix E[ ( y – E(y) ) ( y – E(y) )*T ].

small correlation implies small off-diagonal terms.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unitii-140624081014-phpapp02/85/Unit-ii-13-320.jpg)

![DFT Properties

Circular shift u(n-l)c = x[(n-l)mod N]

The DFT and unitary DFT matrices are

symmetric i.e. F-1 = F*

DFT of length N can be implemented by a fast

algorithm in O(N log2N) operations.

DFT of a real sequence {x(n), n=0,…,N-1} is

conjugate symmetric about N/2.

i.e. y*(N-k) = y(k)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unitii-140624081014-phpapp02/85/Unit-ii-15-320.jpg)

![The Haar transform

The Haar functions hk(x) are defined on a continuous

interval, x [0,1], and for k = 0,…,N-1, where N = 2n.

The integer k can be uniquely decomposed as k = 2p + q -1

where 0 ≤ p ≤ n-1; q=0,1 for p=0 and 1 ≤ q ≤ 2p for p≠0. For

example, when, N=4

k 0 1 2 3

p 0 0 1 1

q 0 1 1 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unitii-140624081014-phpapp02/85/Unit-ii-30-320.jpg)

![The Haar transform

•The Haar functions are defined as

0 0,0

/ 2

/ 2

,

1

( ) ( ) , [0,1]

1

1 22 ,

2 2

1

1 2( ) 2 ,

2 2

0, [0,1]

p

p p

p

k p q p p

h x h x x

N

q

q

x

q

q

h x h x

N

otherwise for x

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unitii-140624081014-phpapp02/85/Unit-ii-31-320.jpg)