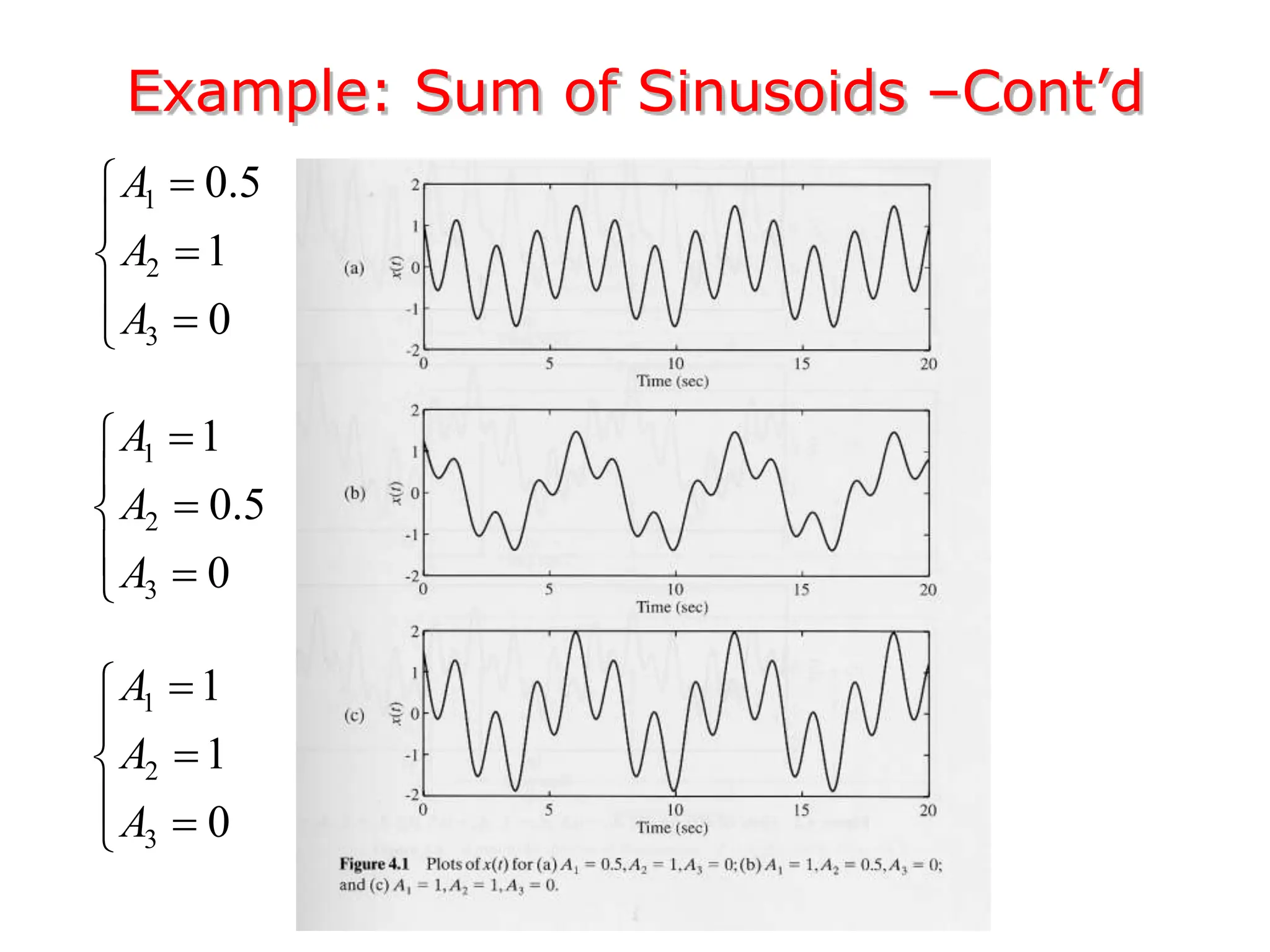

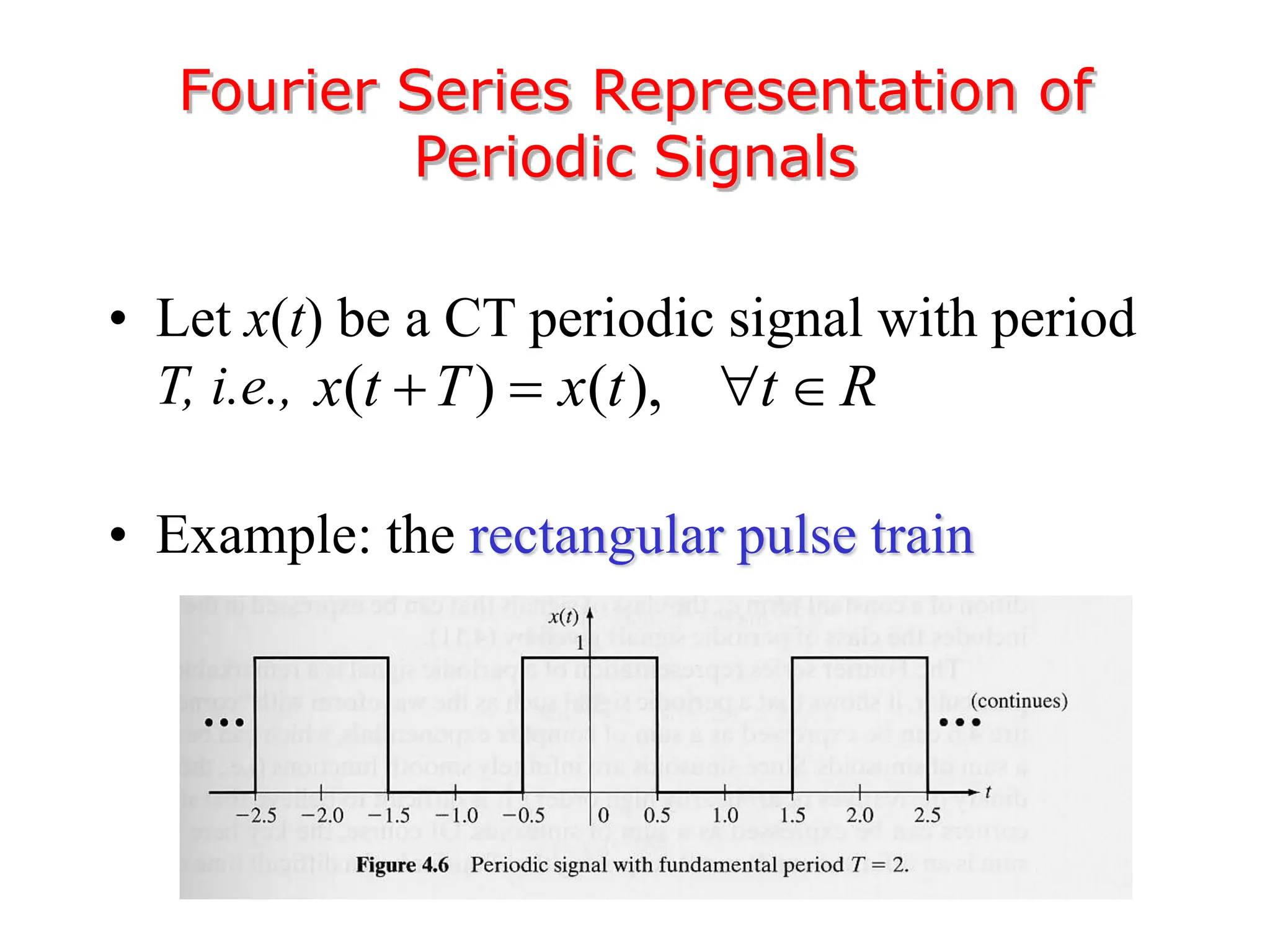

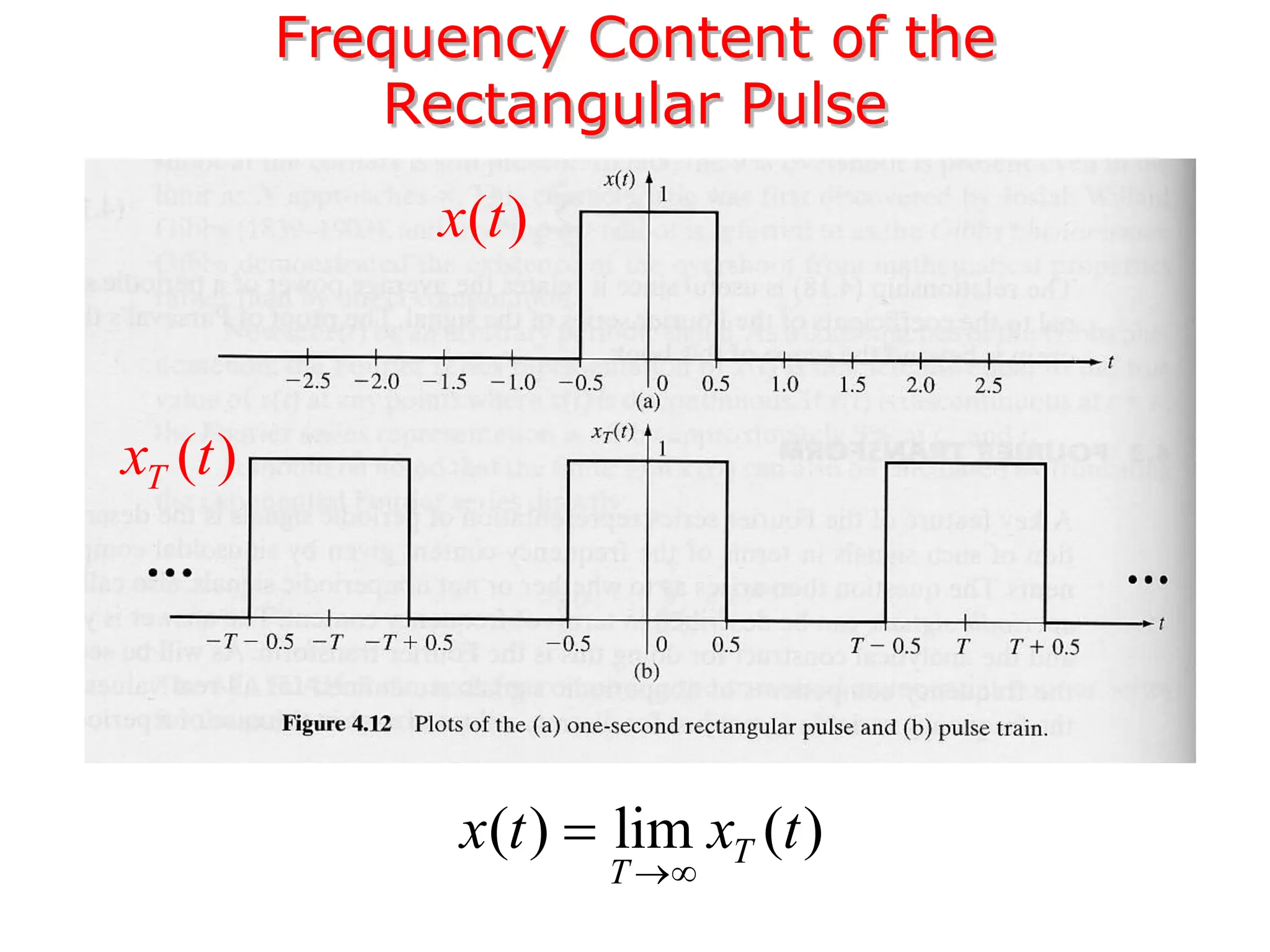

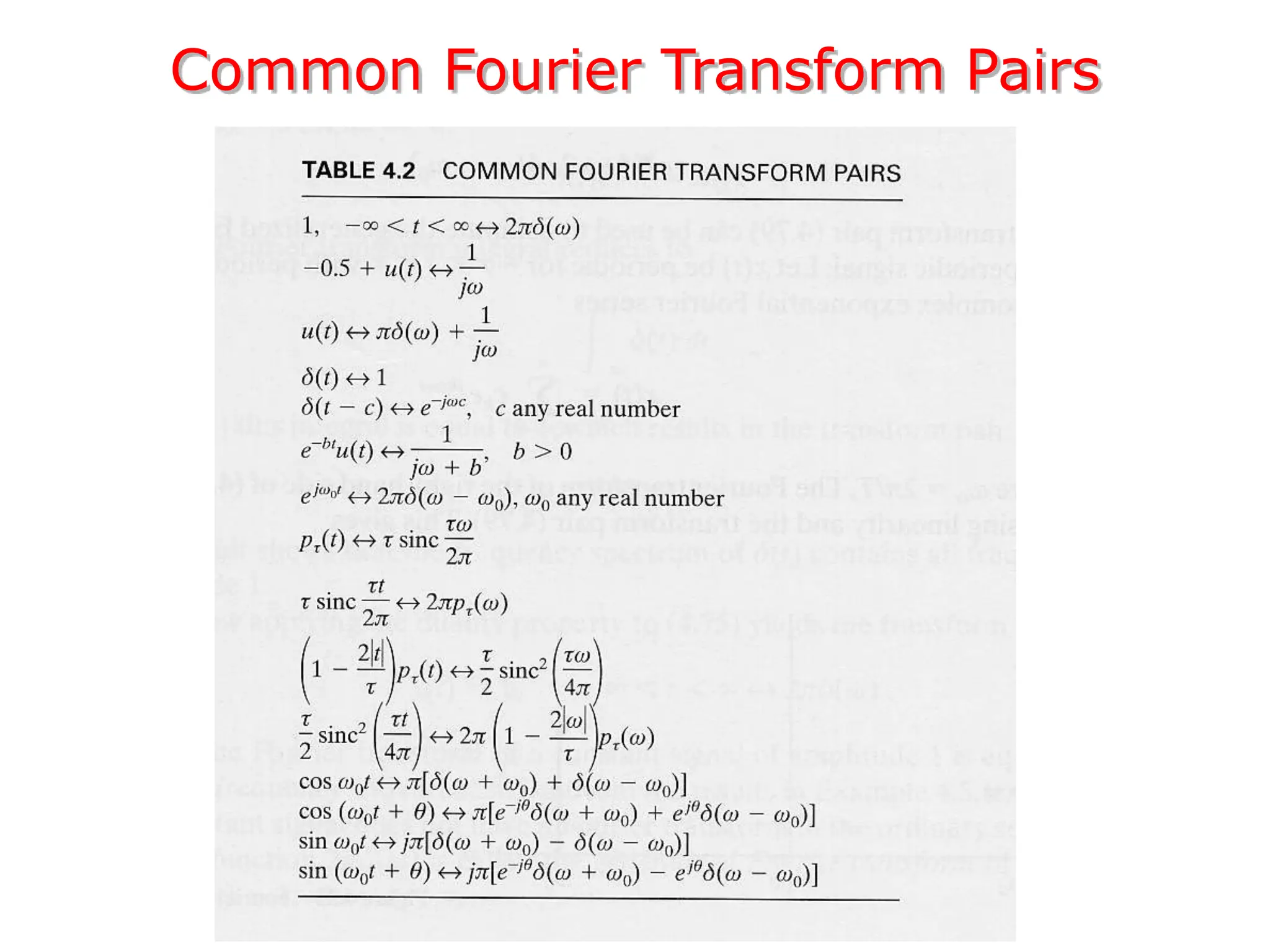

1. The document discusses Fourier analysis techniques for representing signals, including Fourier series and the Fourier transform. It uses the example of a rectangular pulse train to illustrate these concepts.

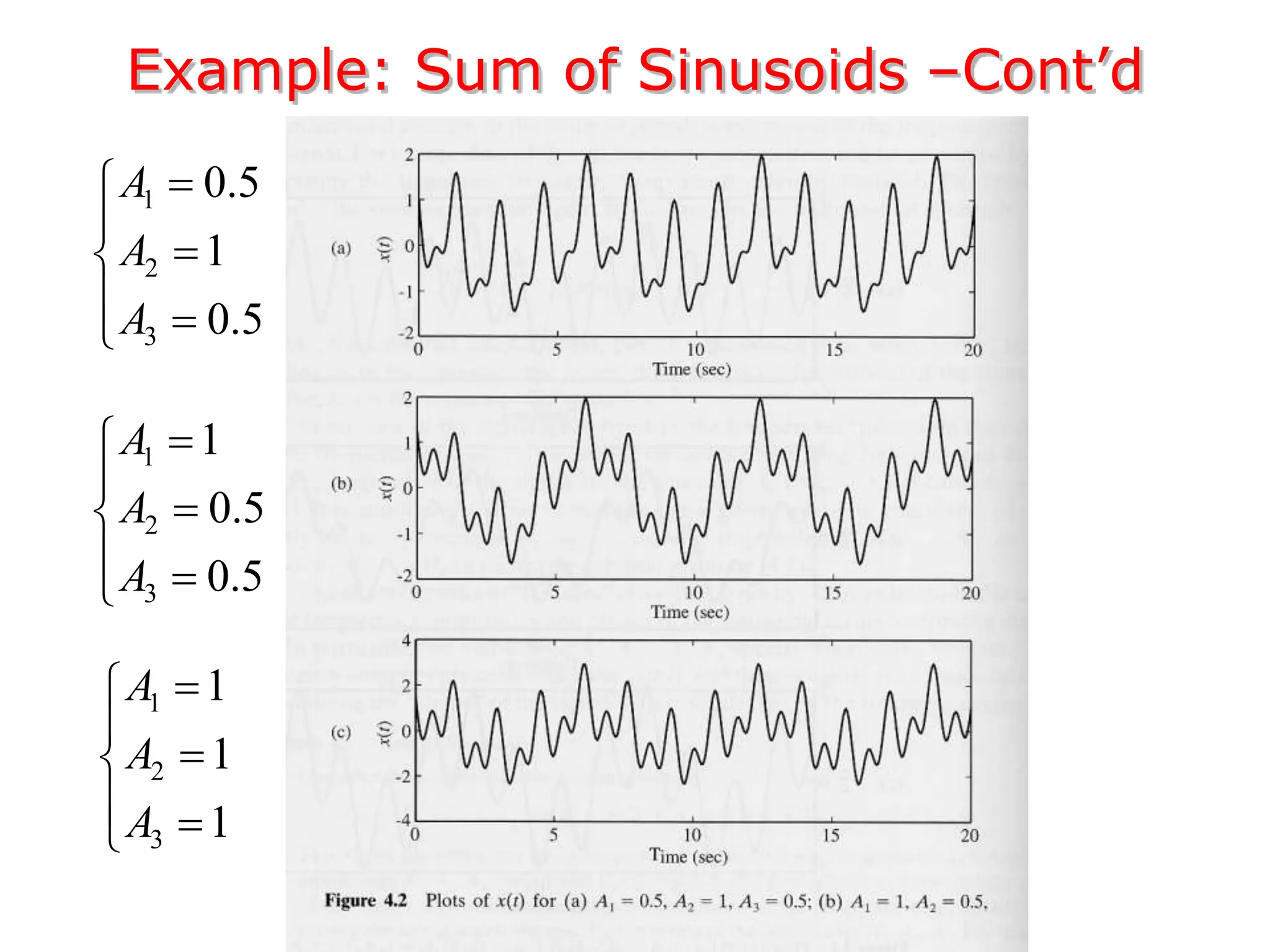

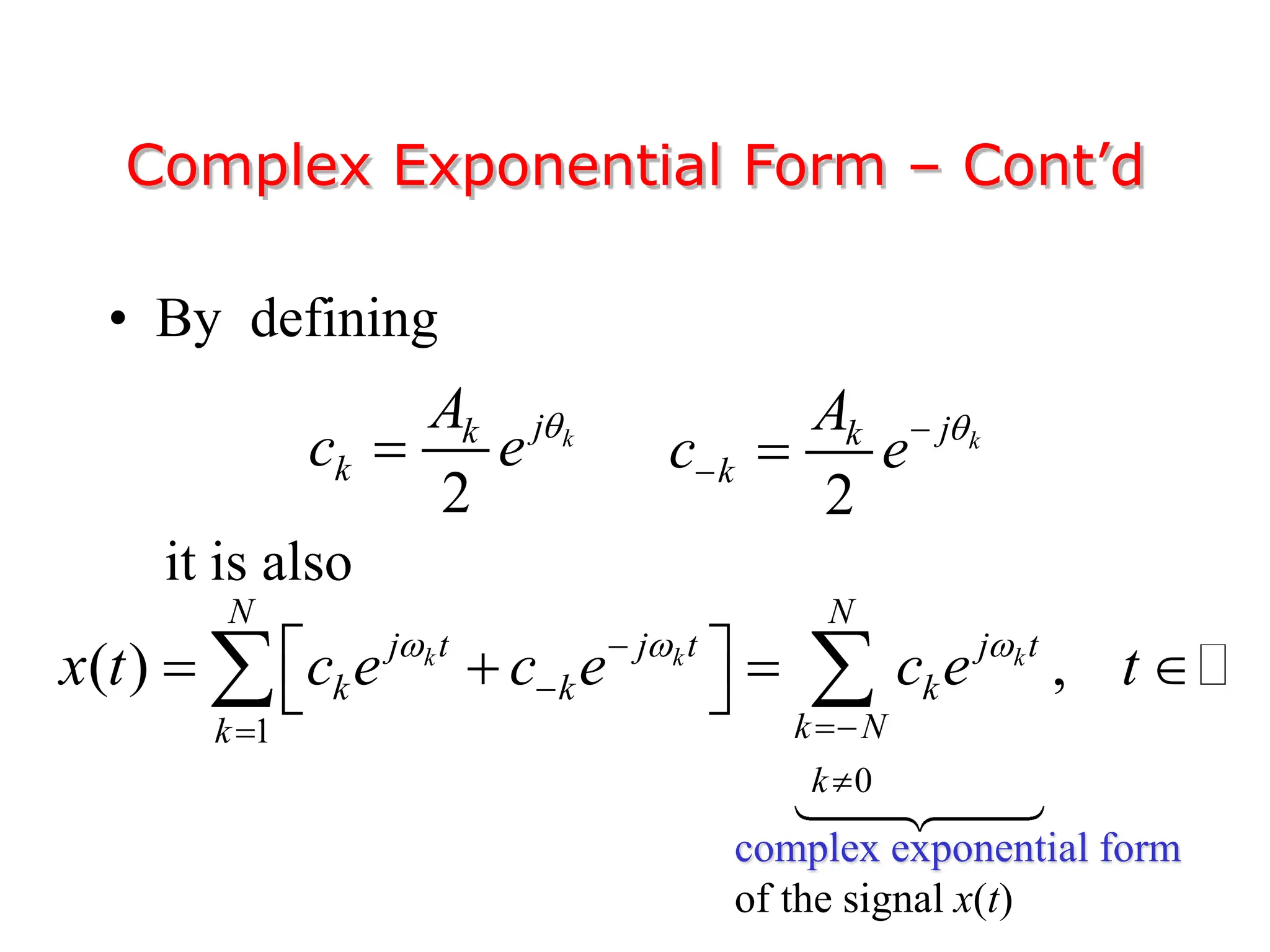

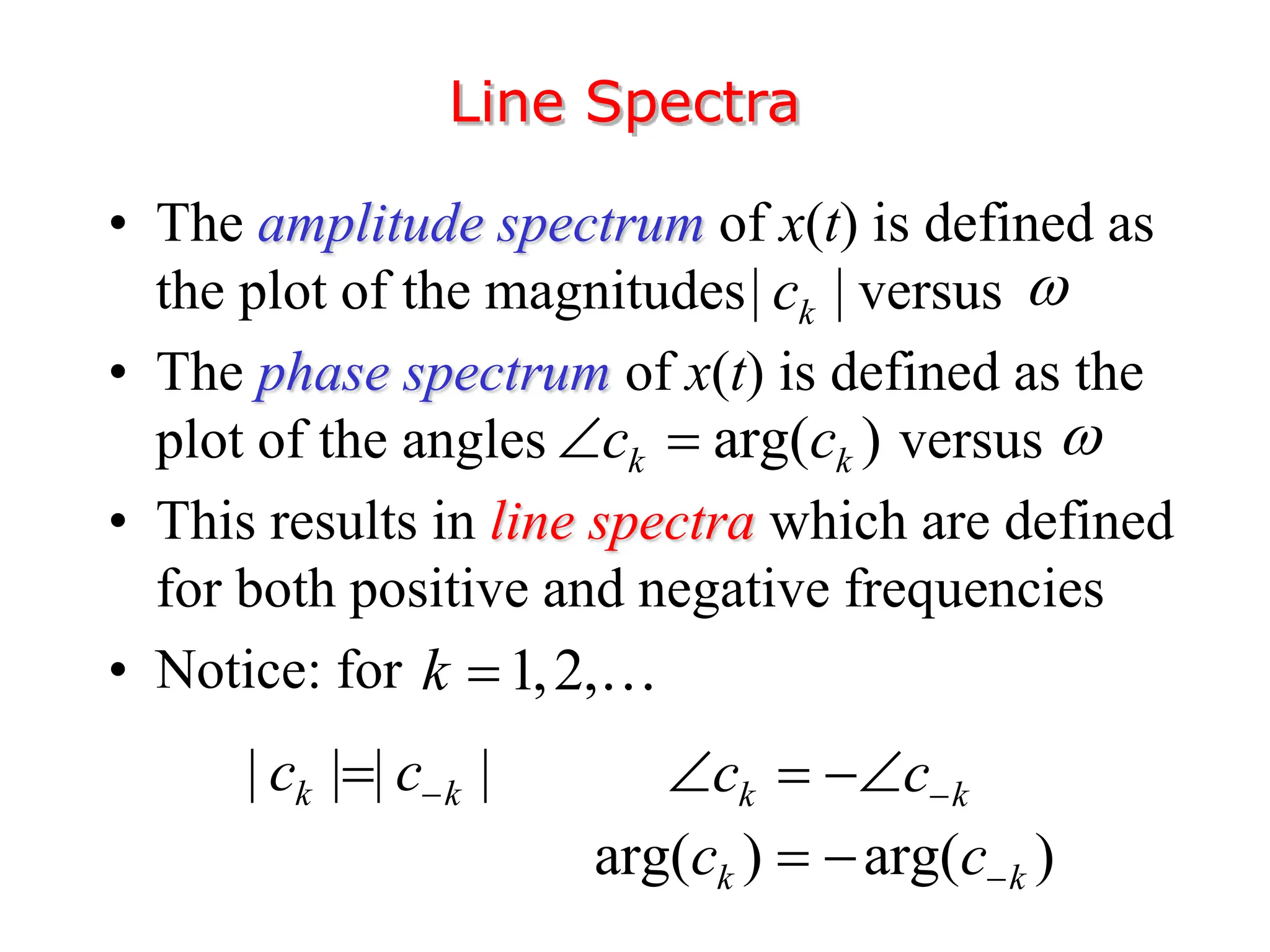

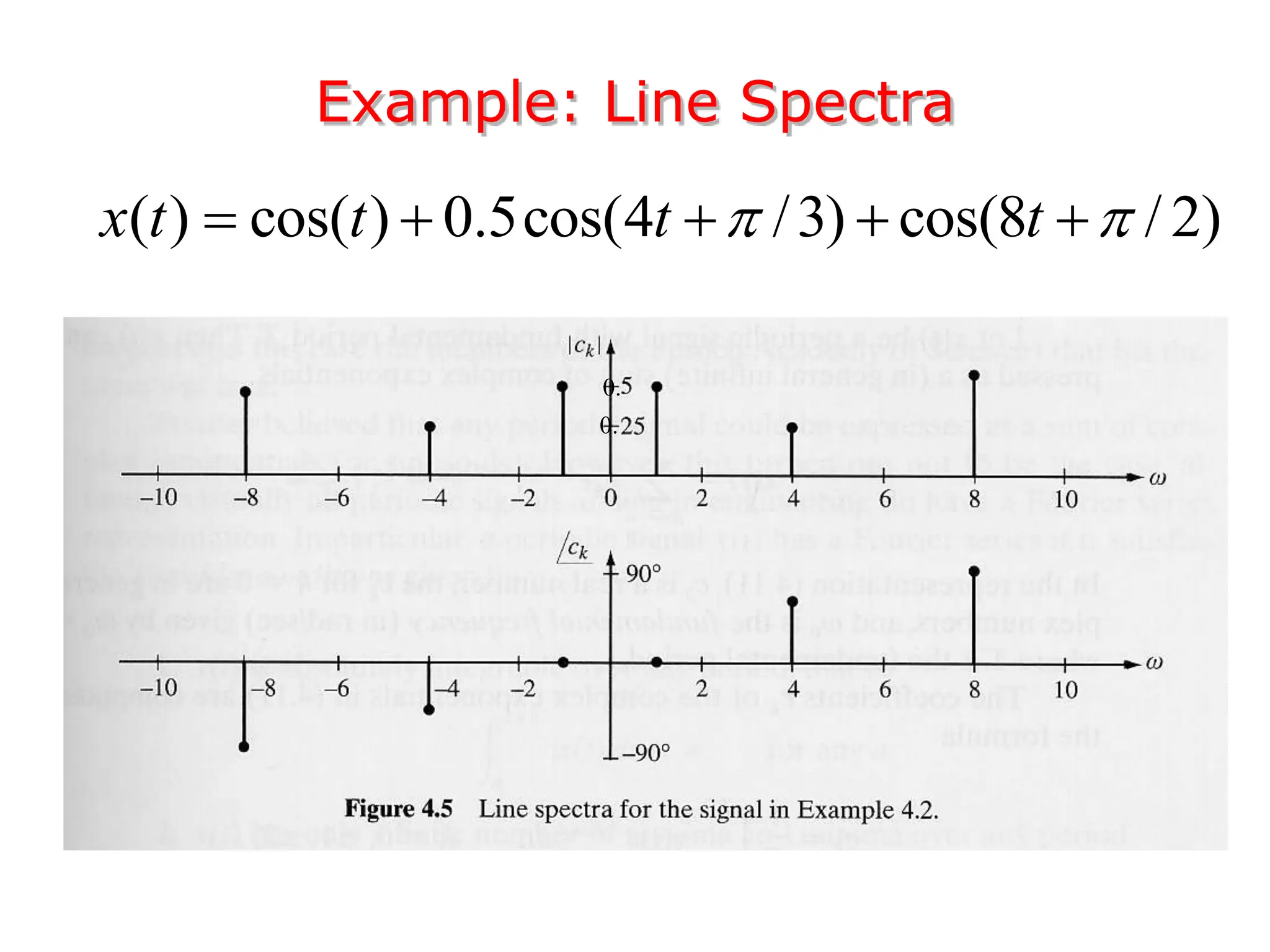

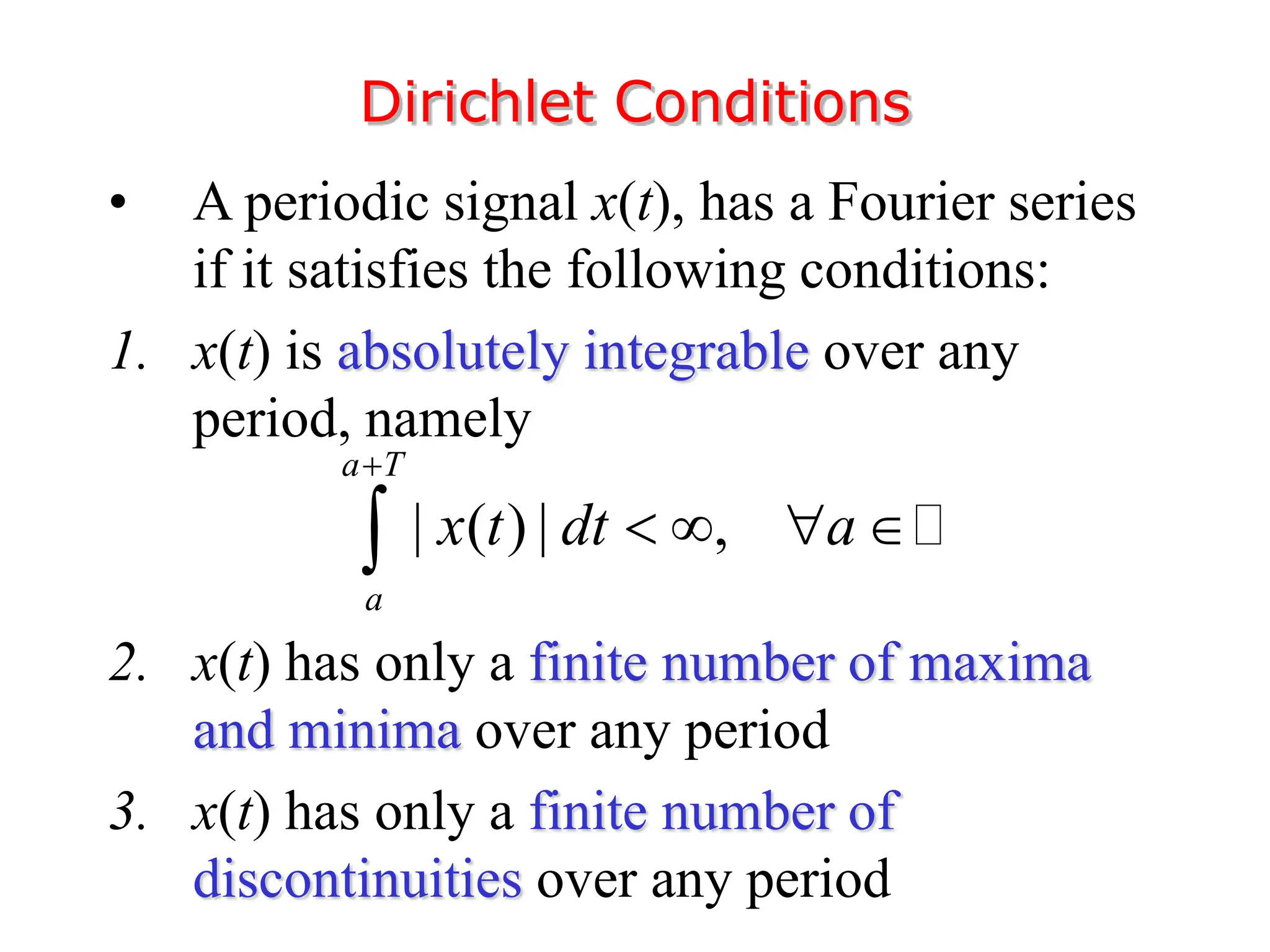

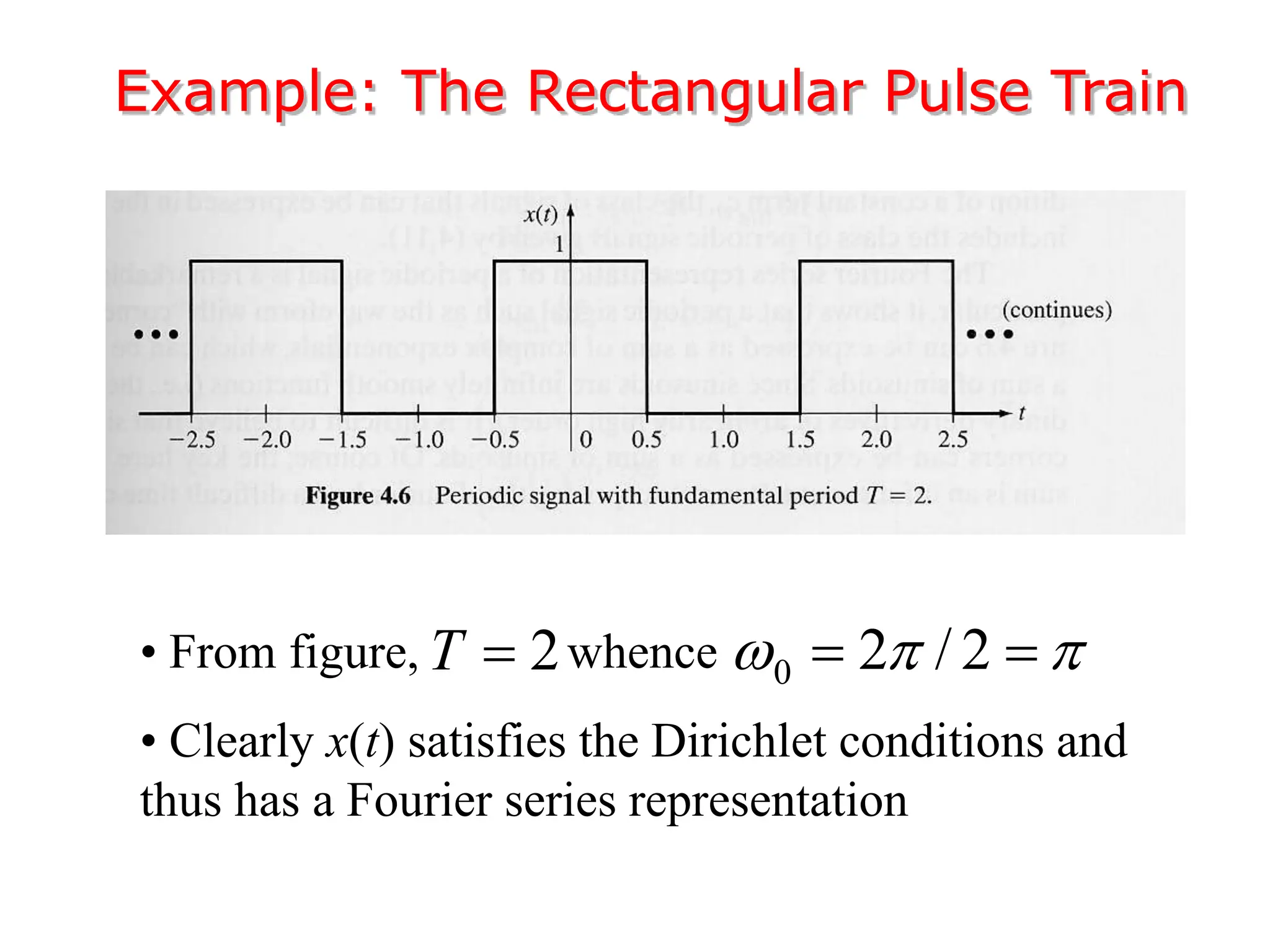

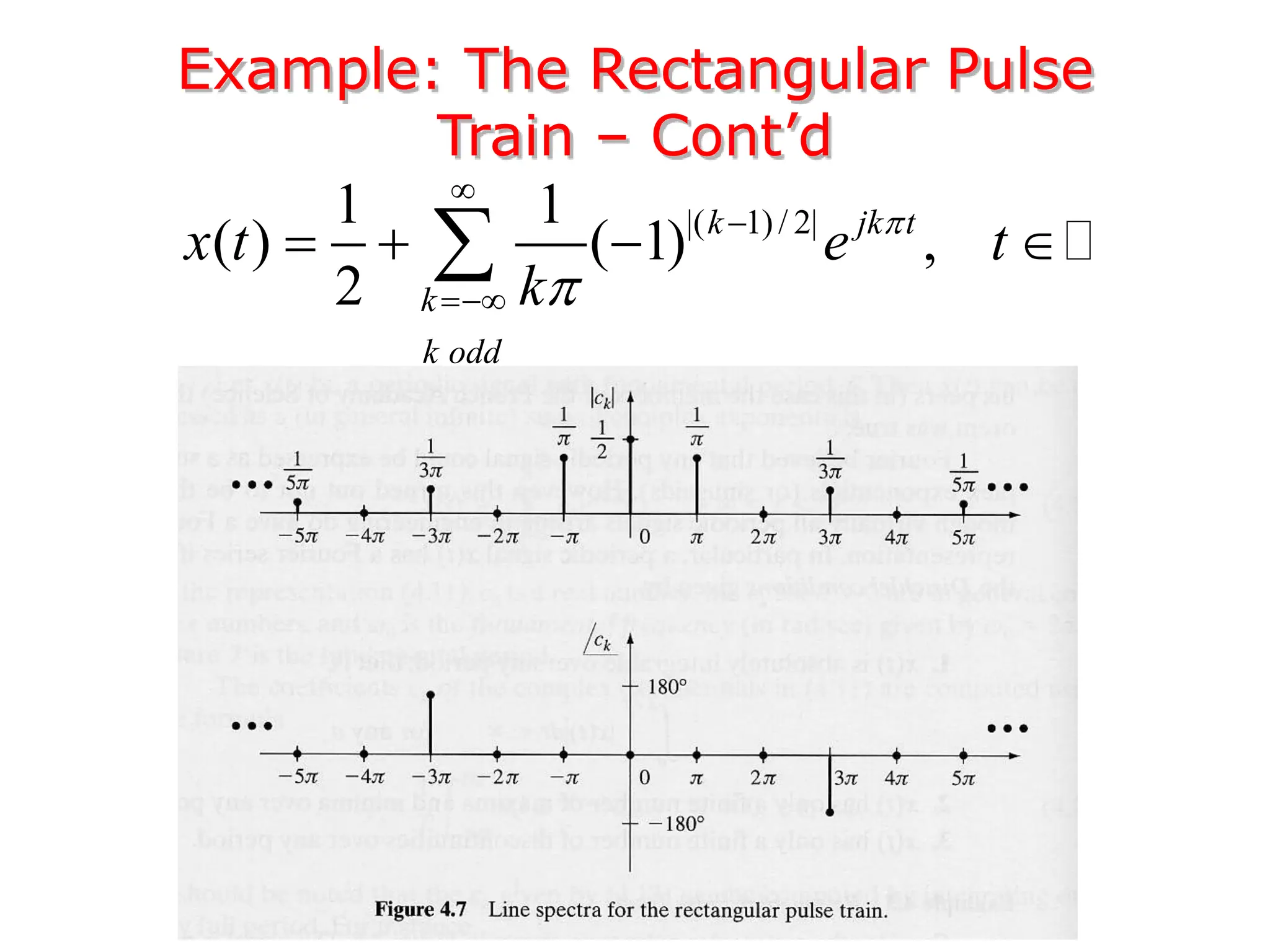

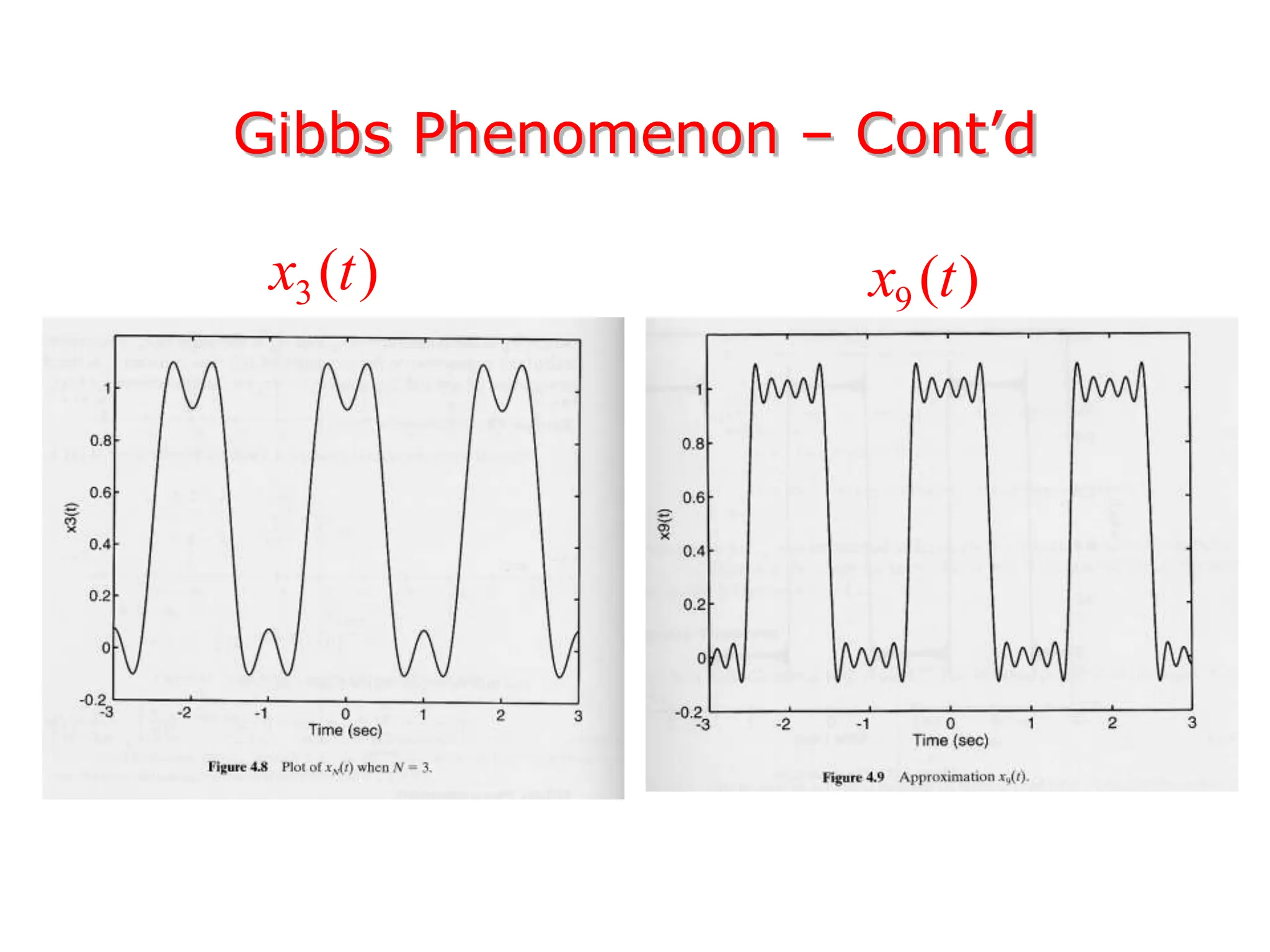

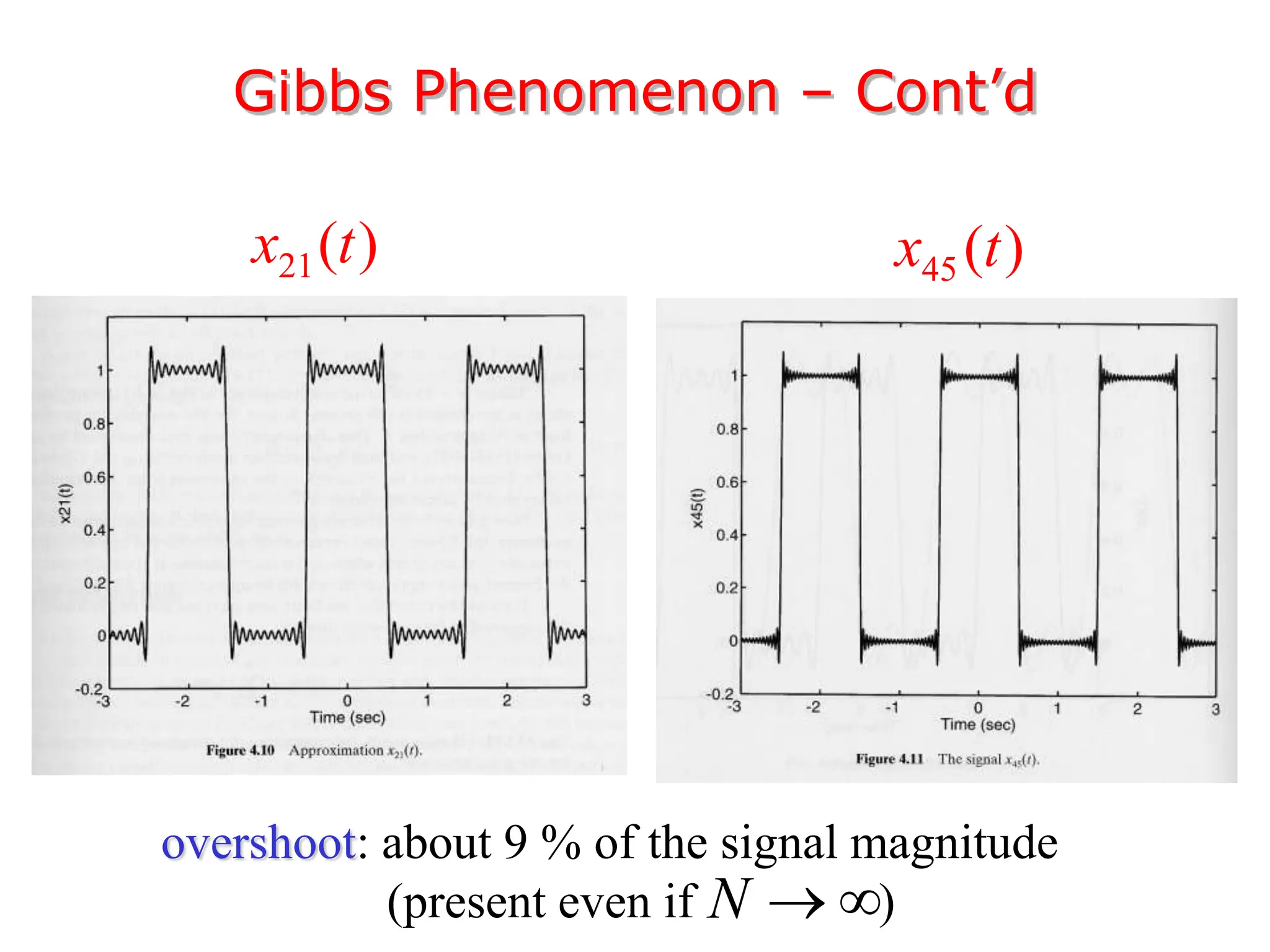

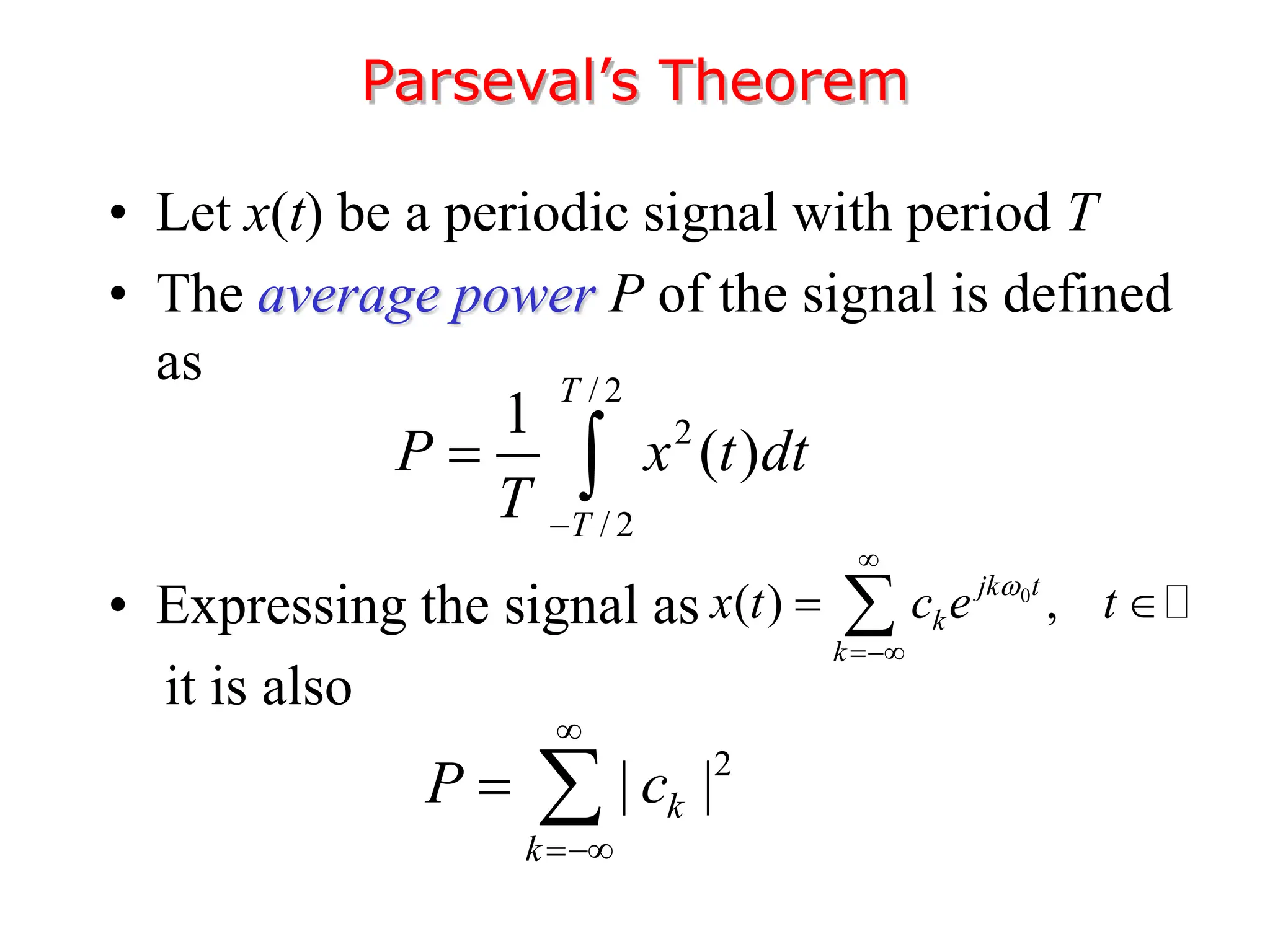

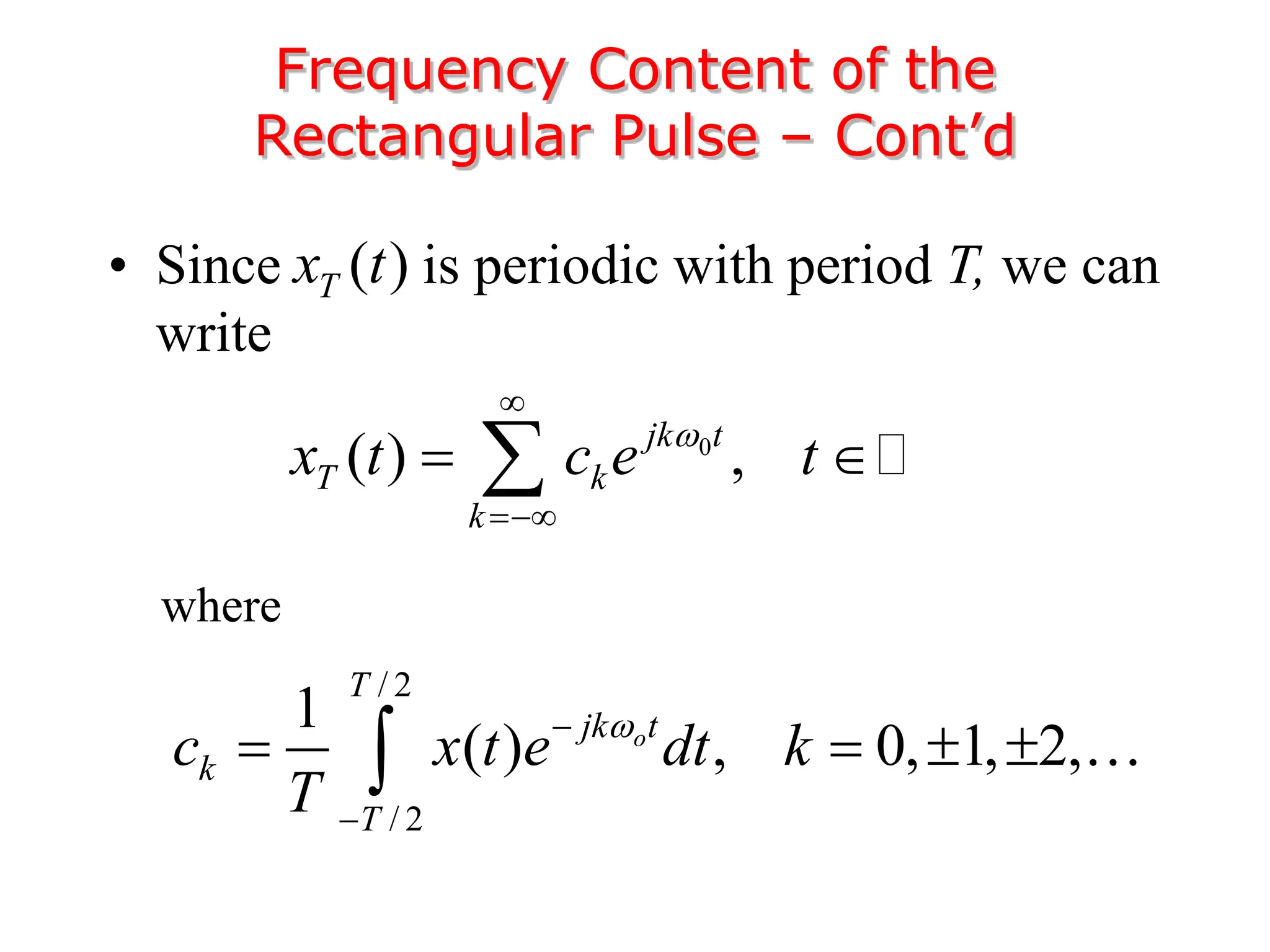

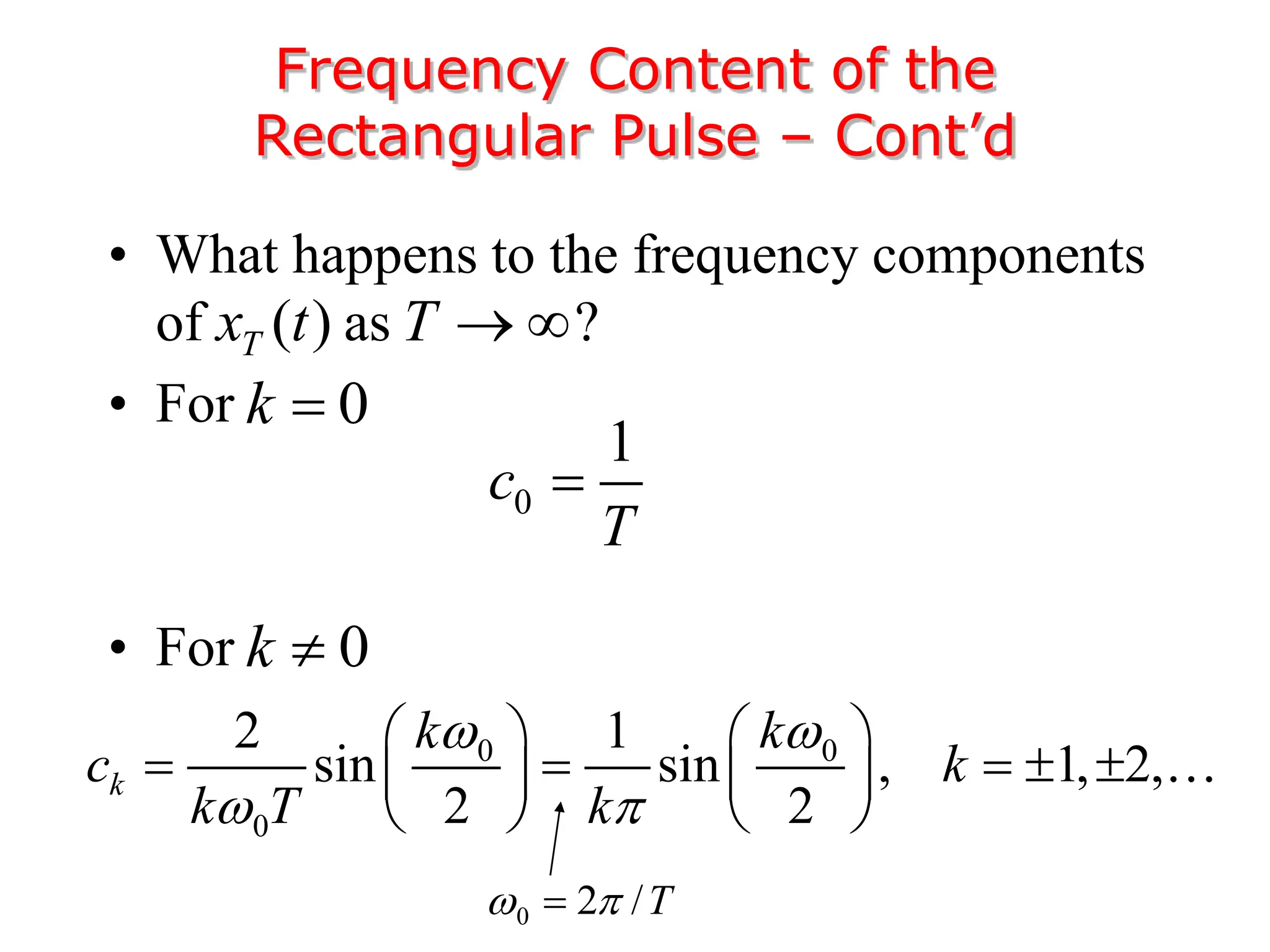

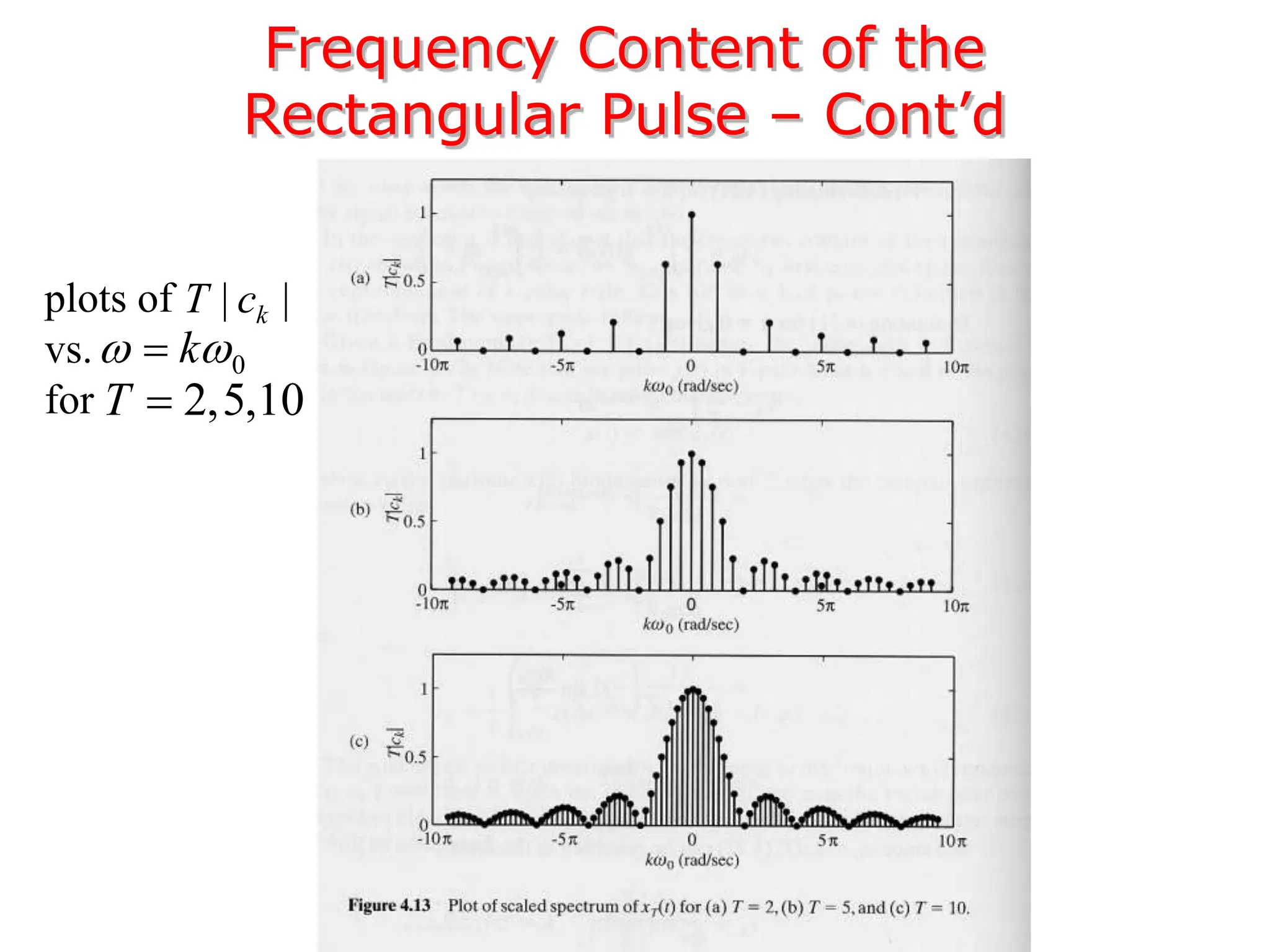

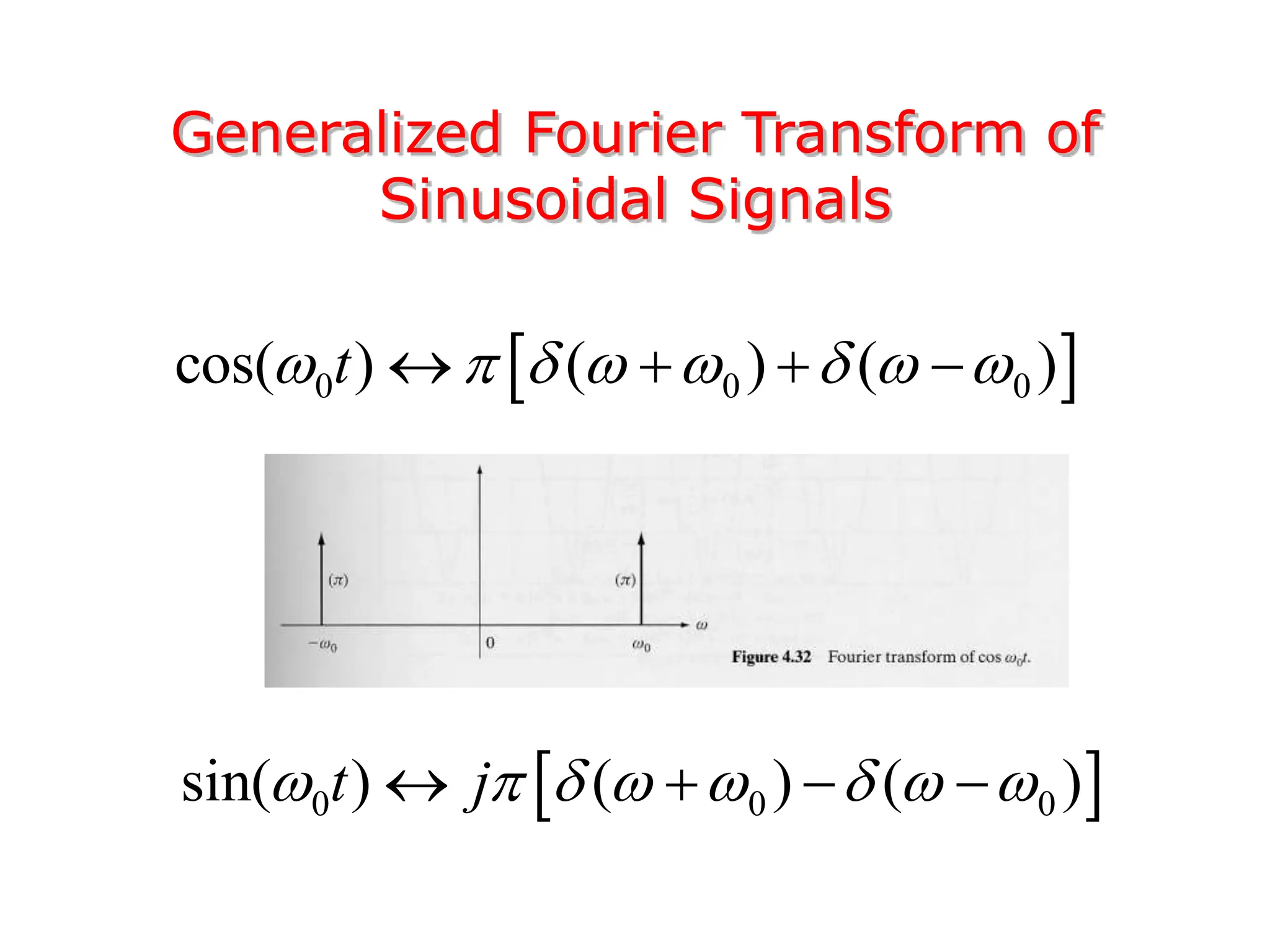

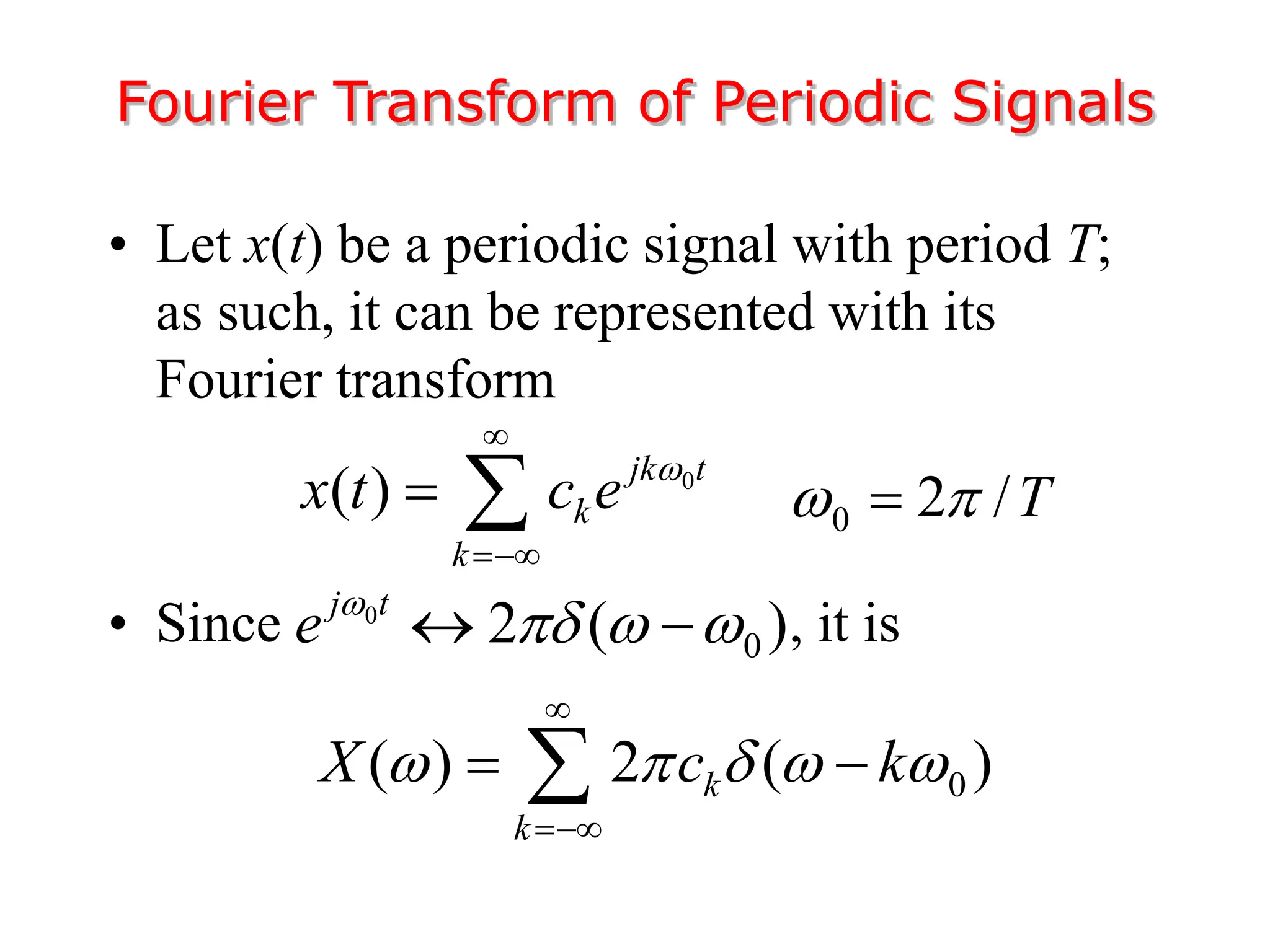

2. A periodic signal like a rectangular pulse train can be represented by a Fourier series as a sum of sinusoids with frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

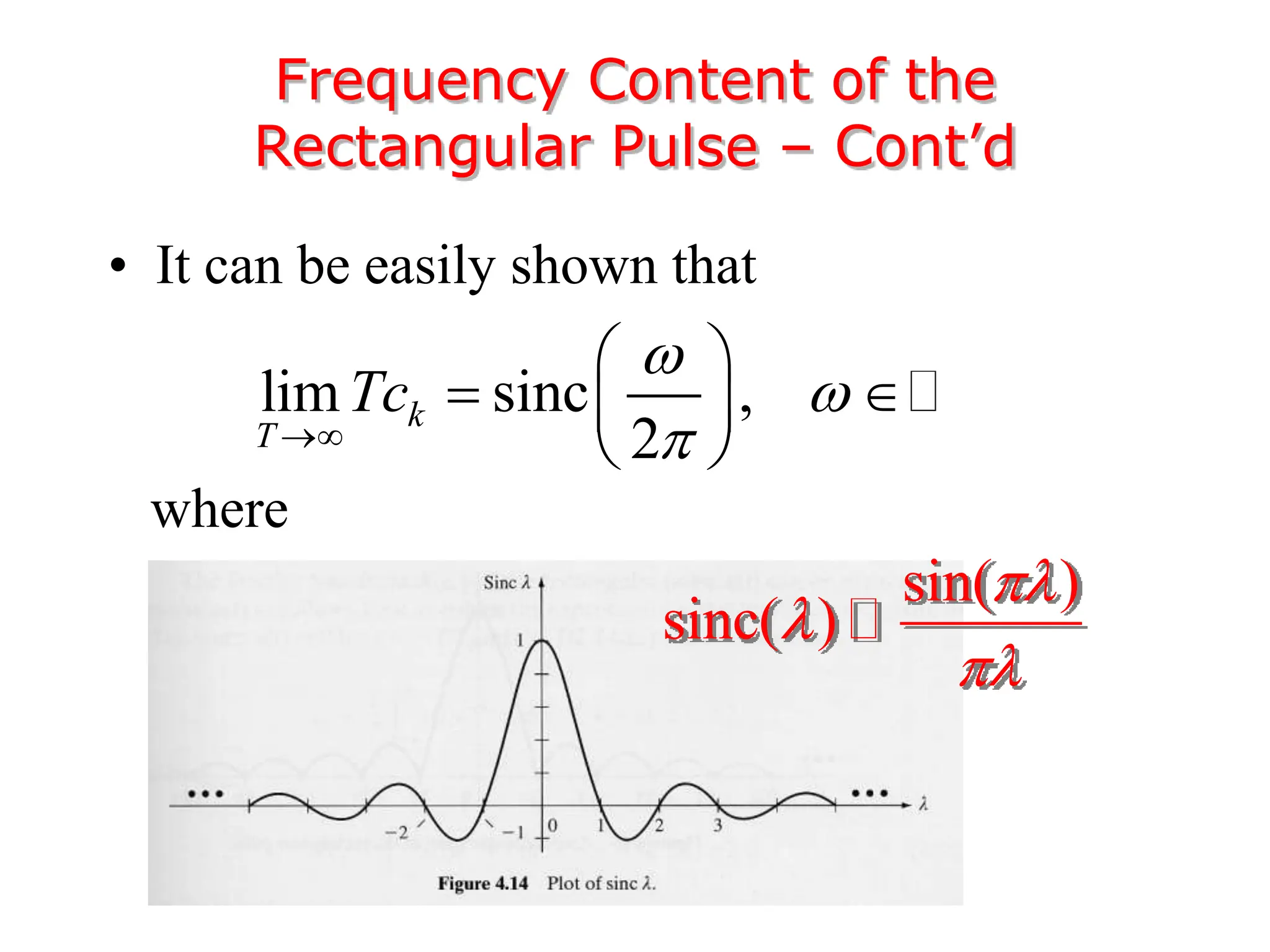

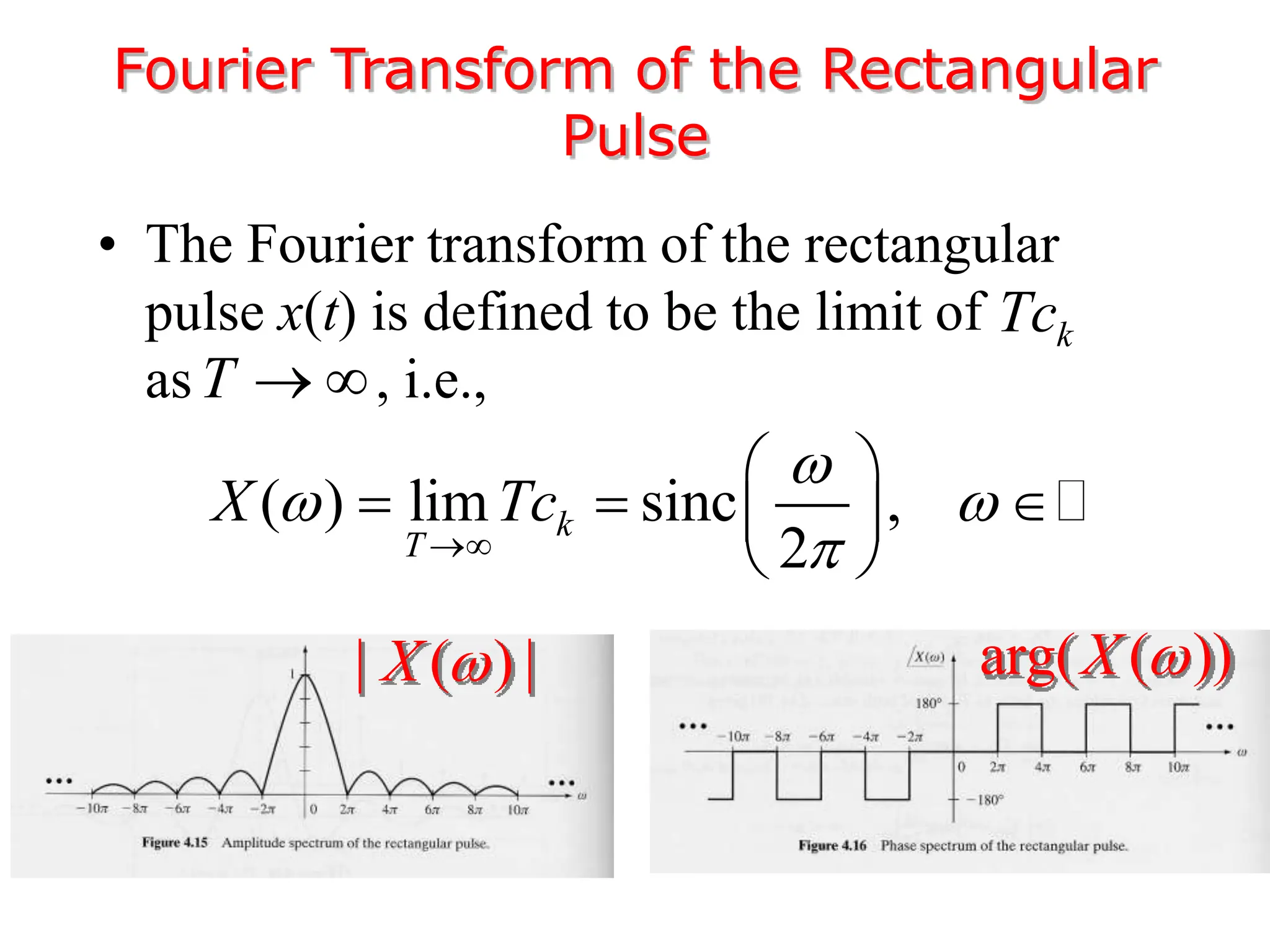

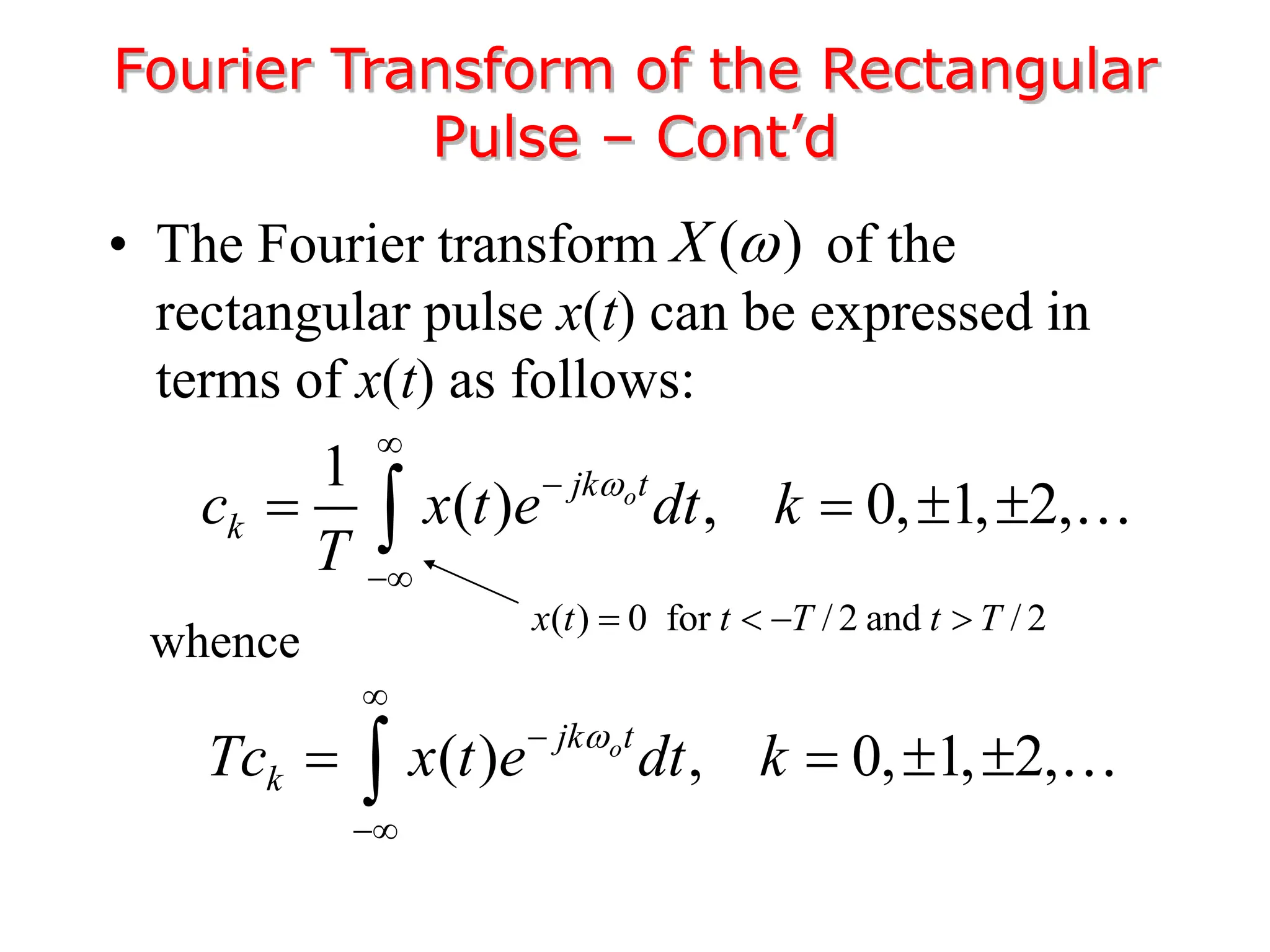

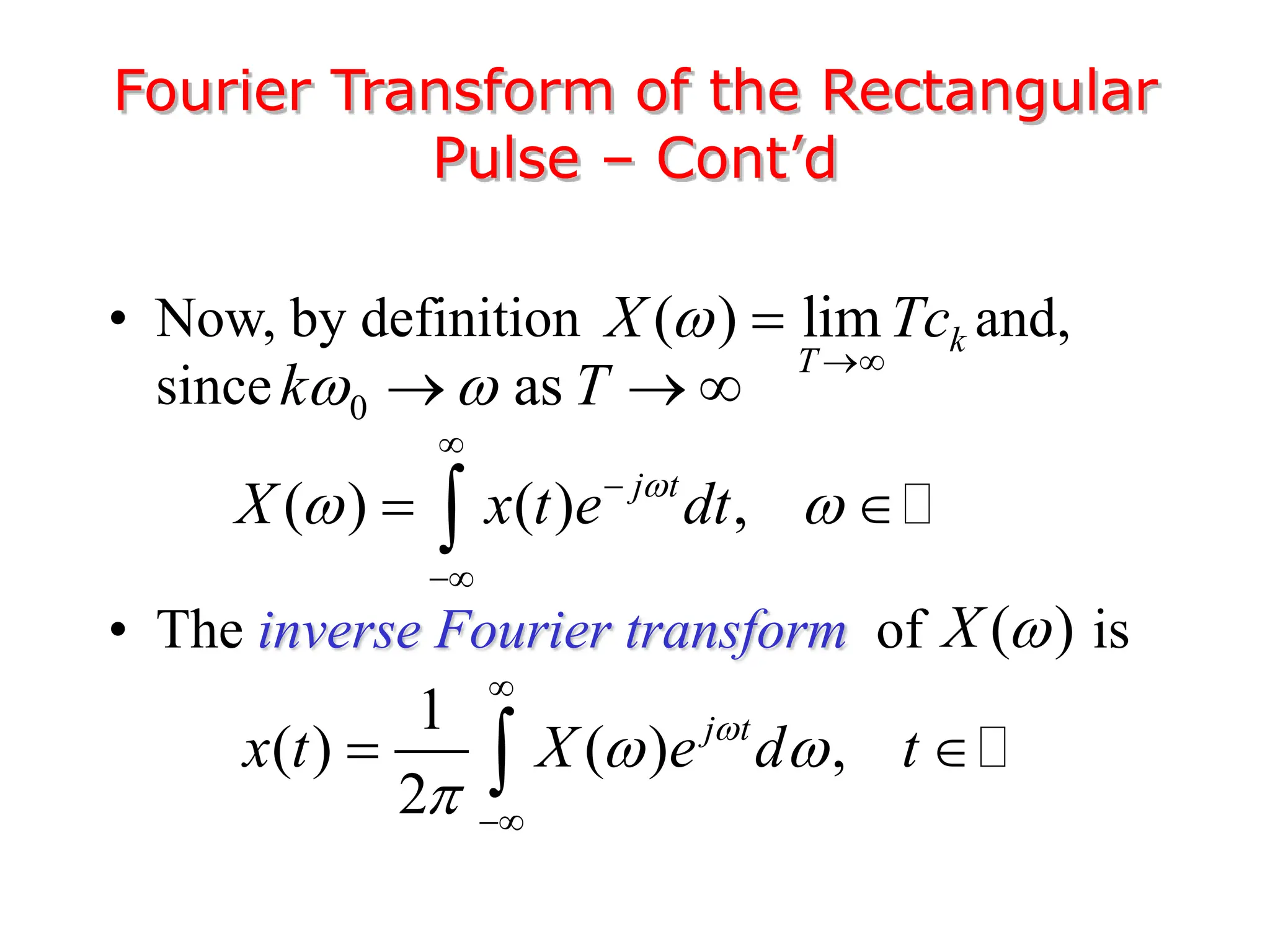

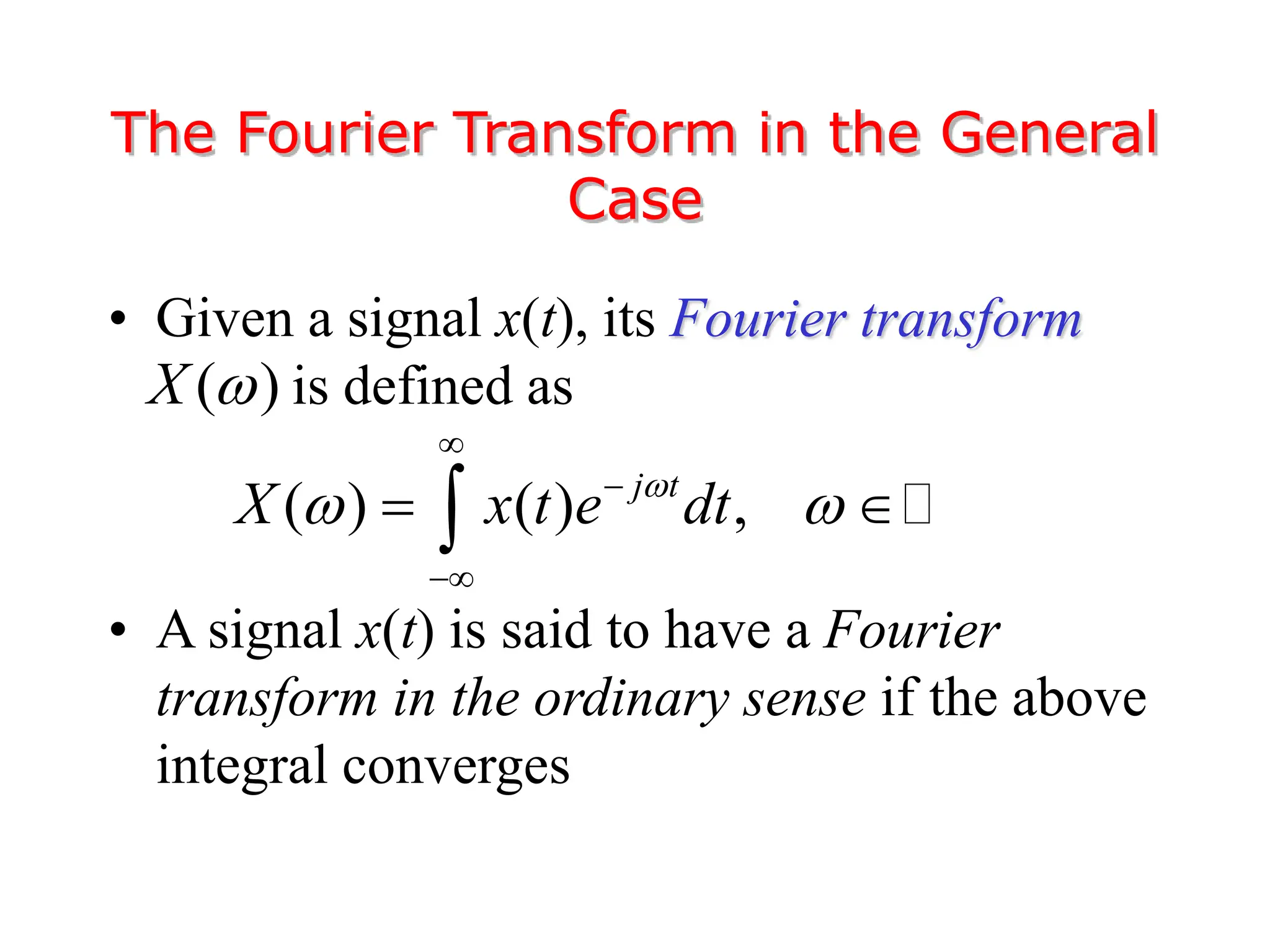

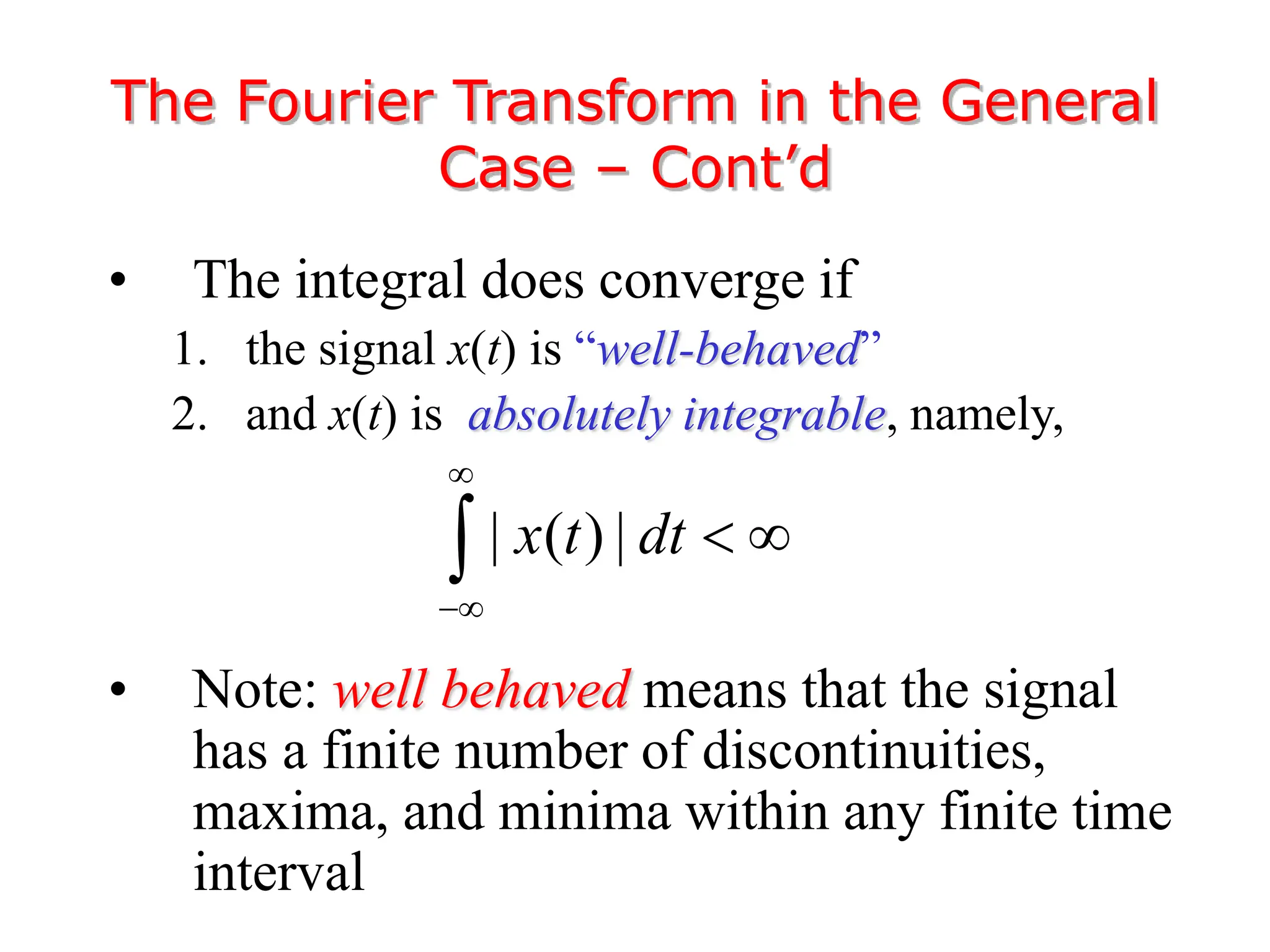

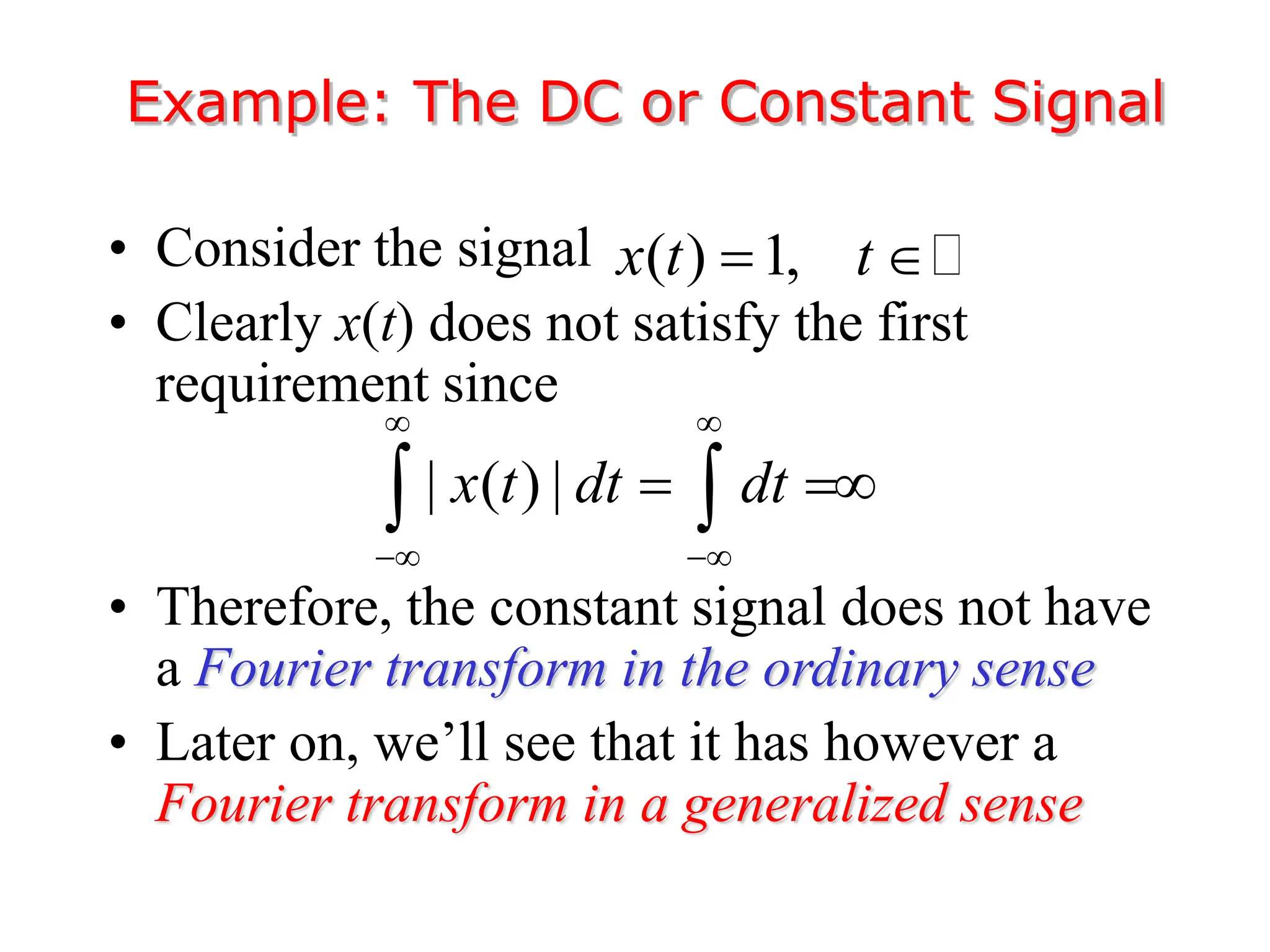

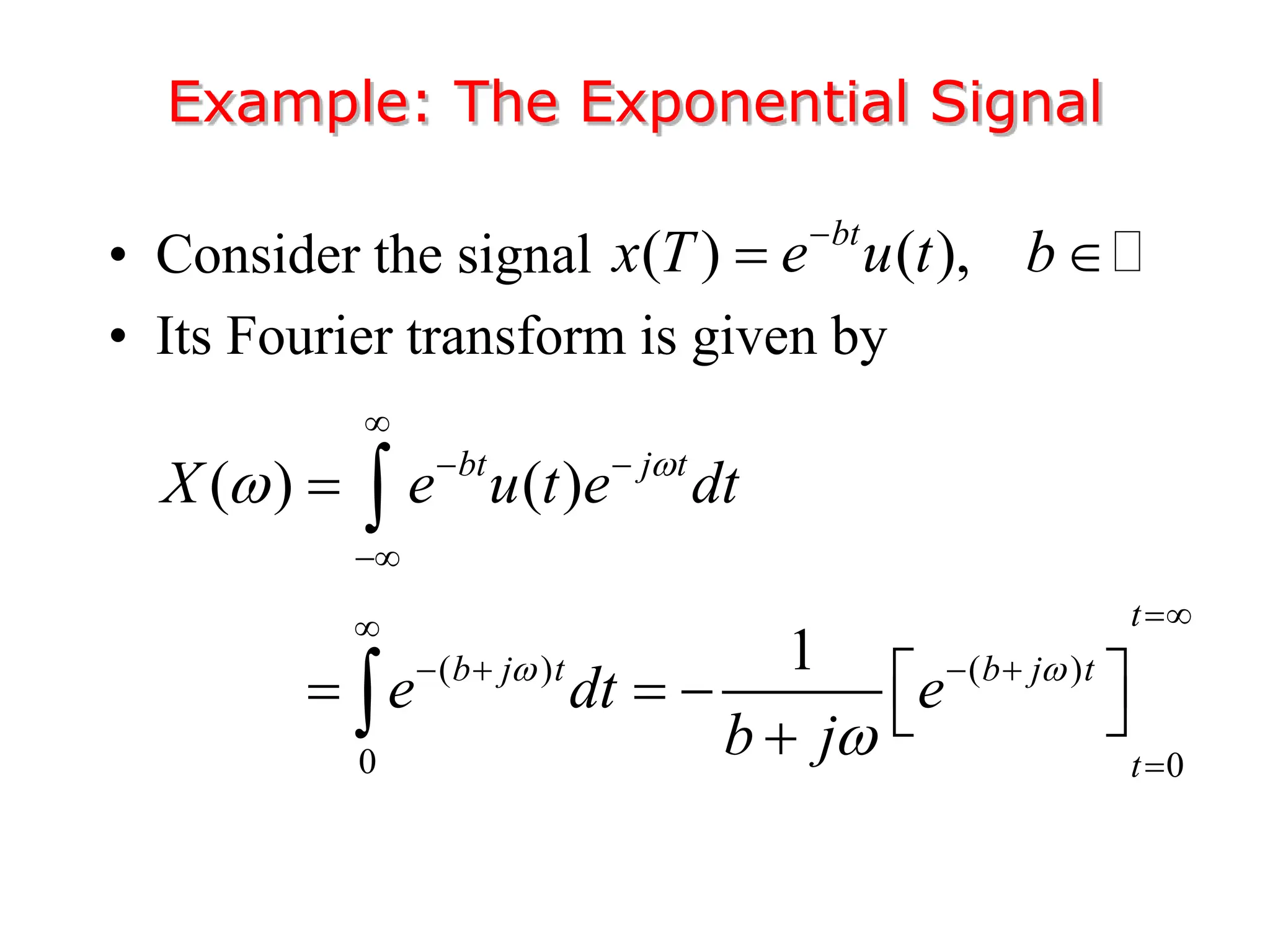

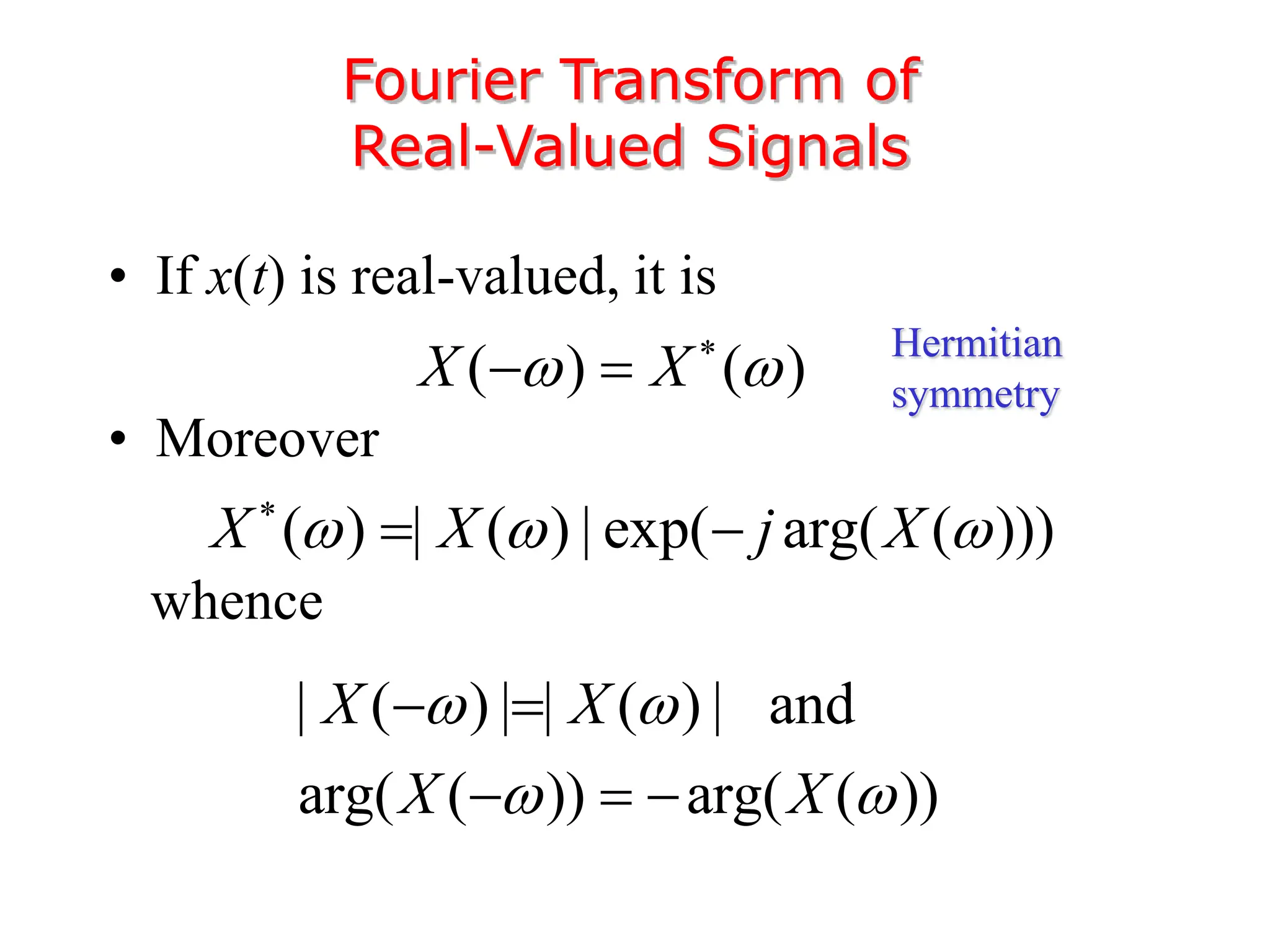

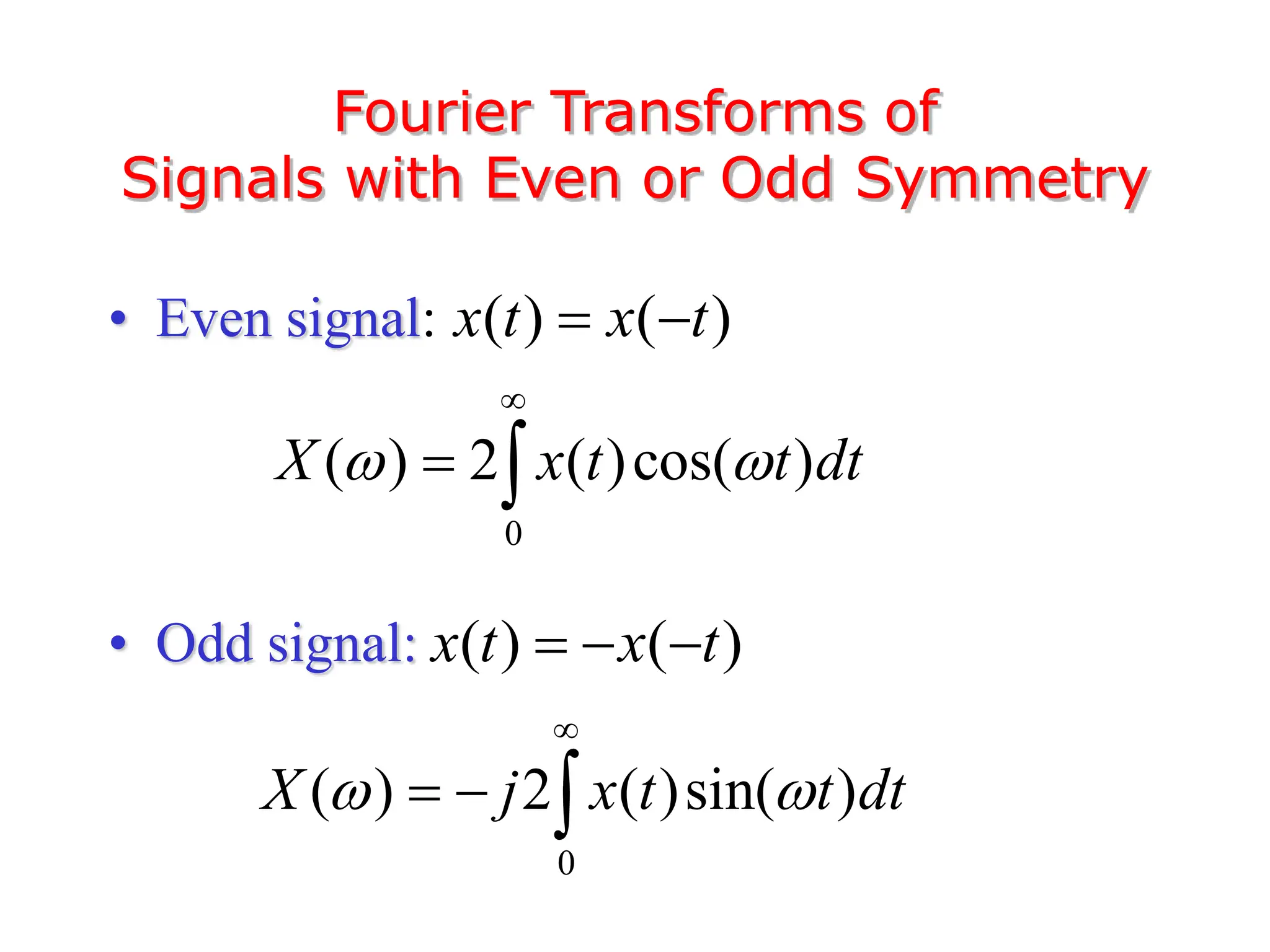

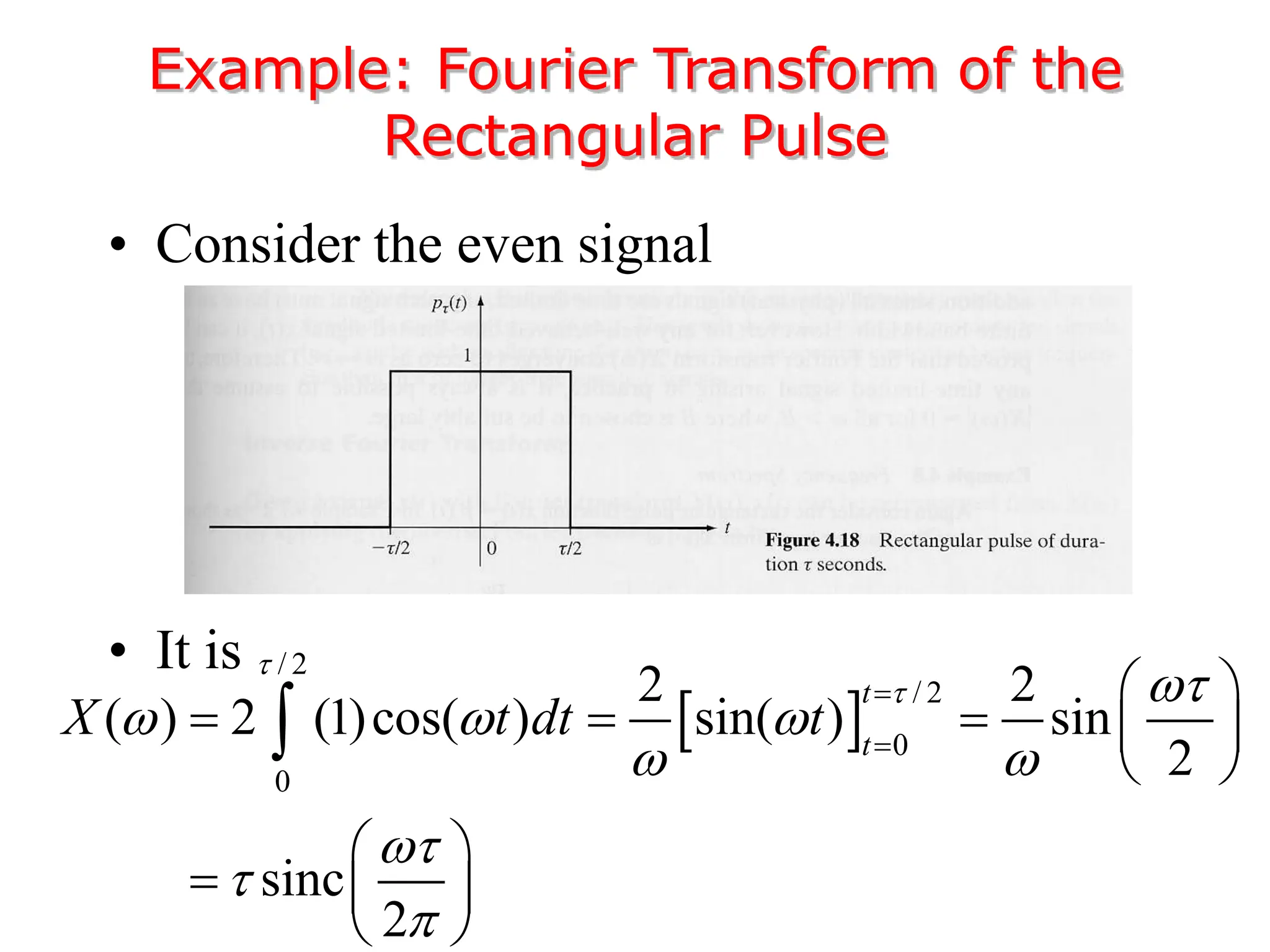

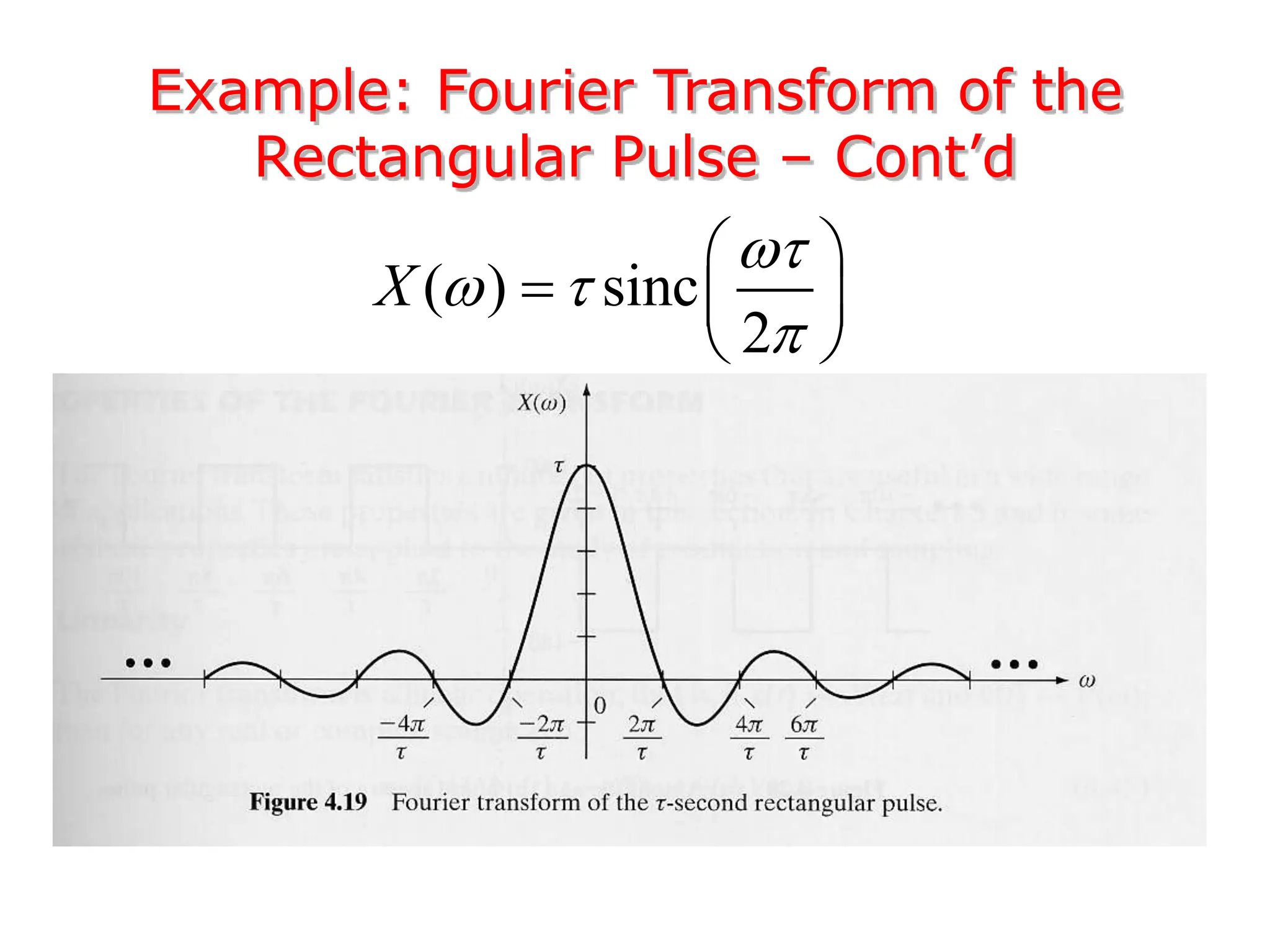

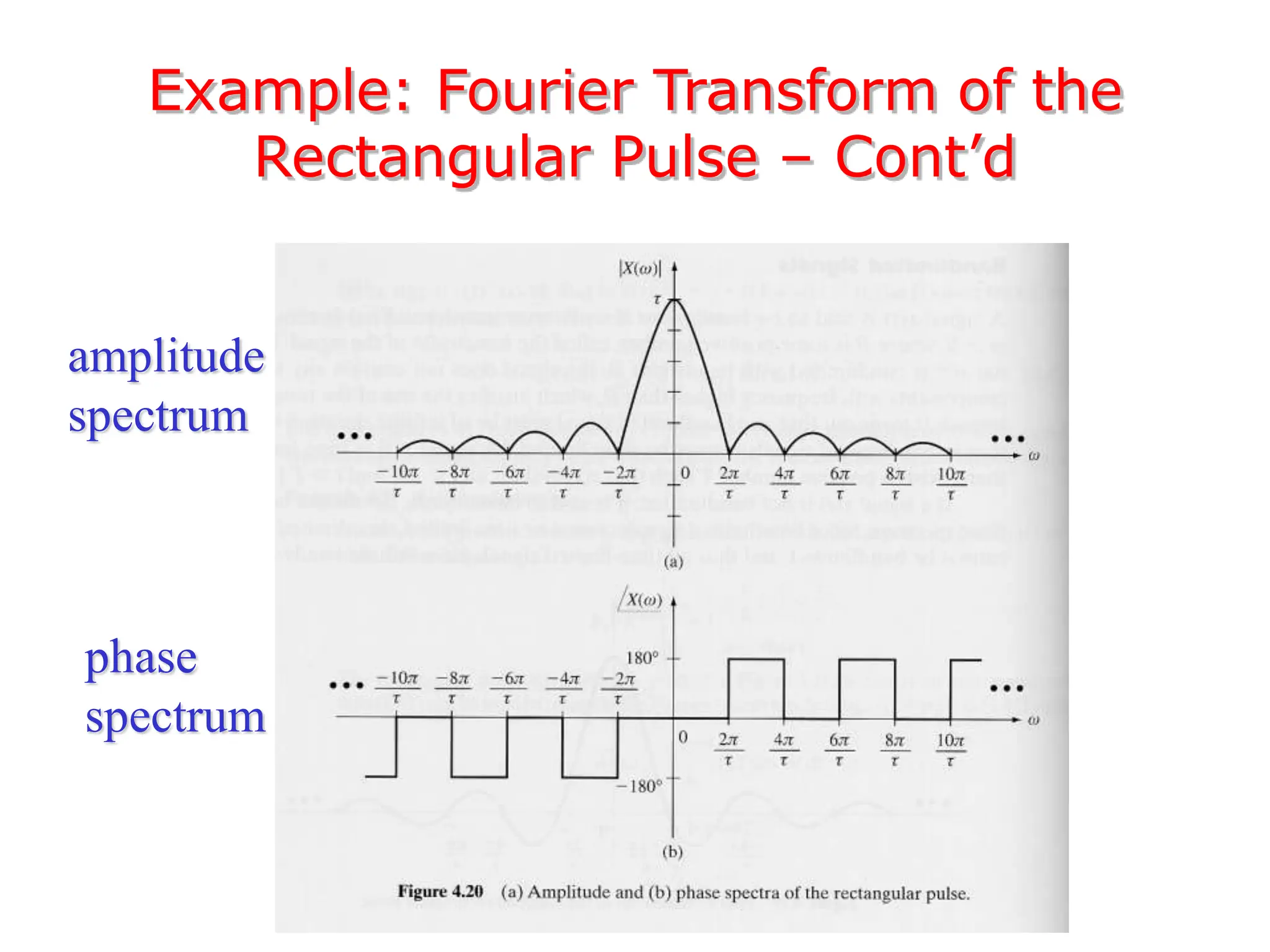

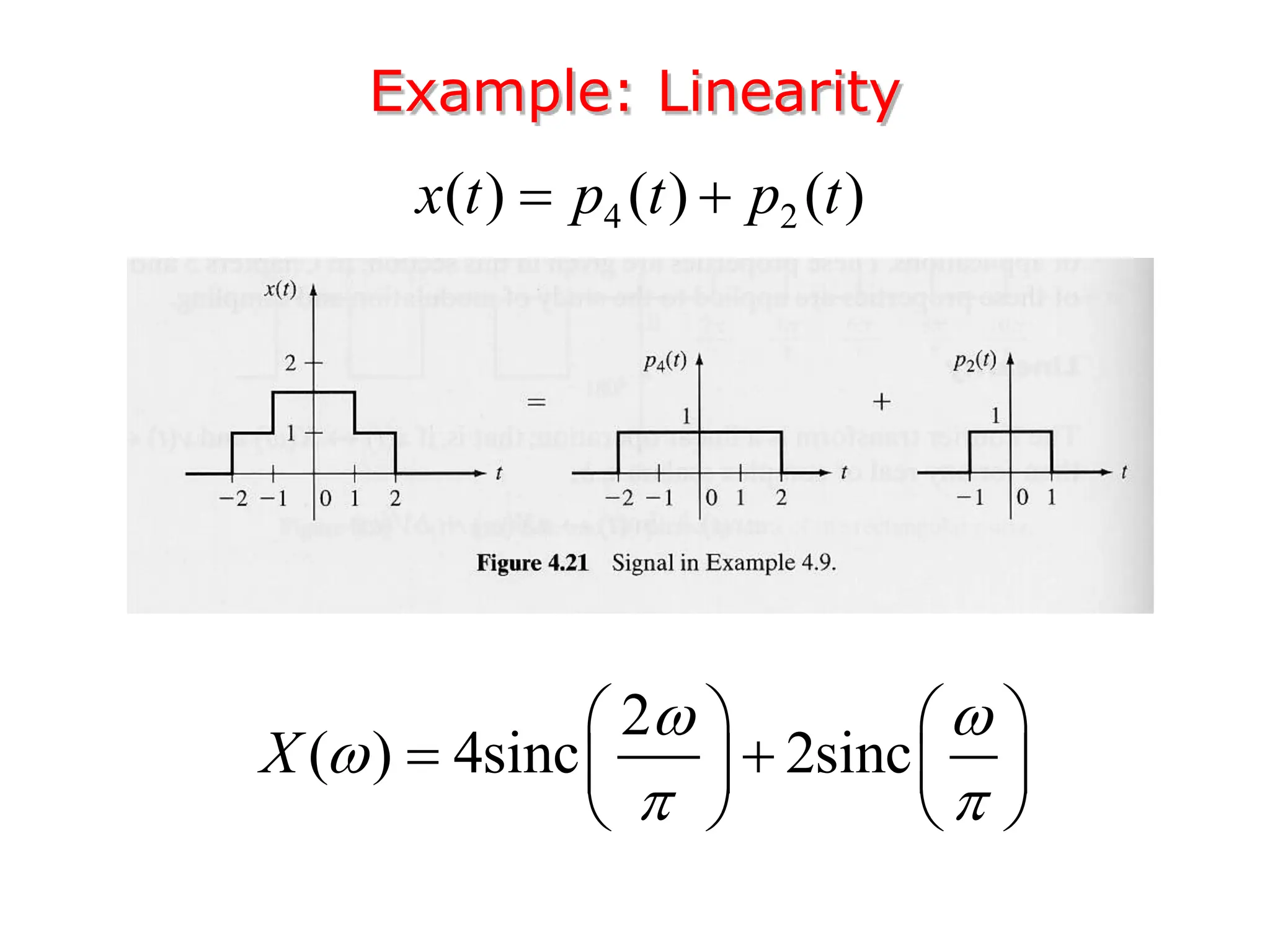

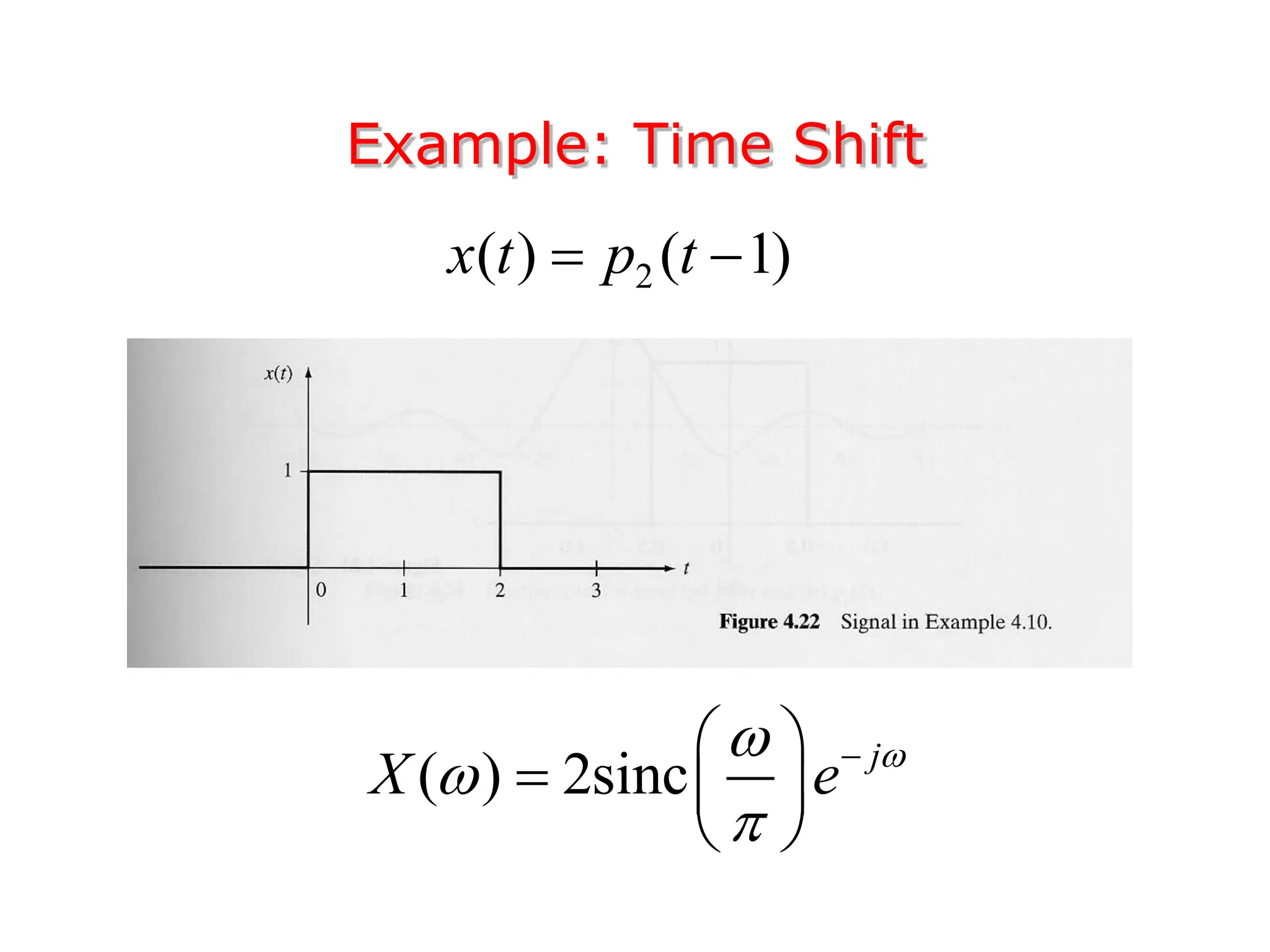

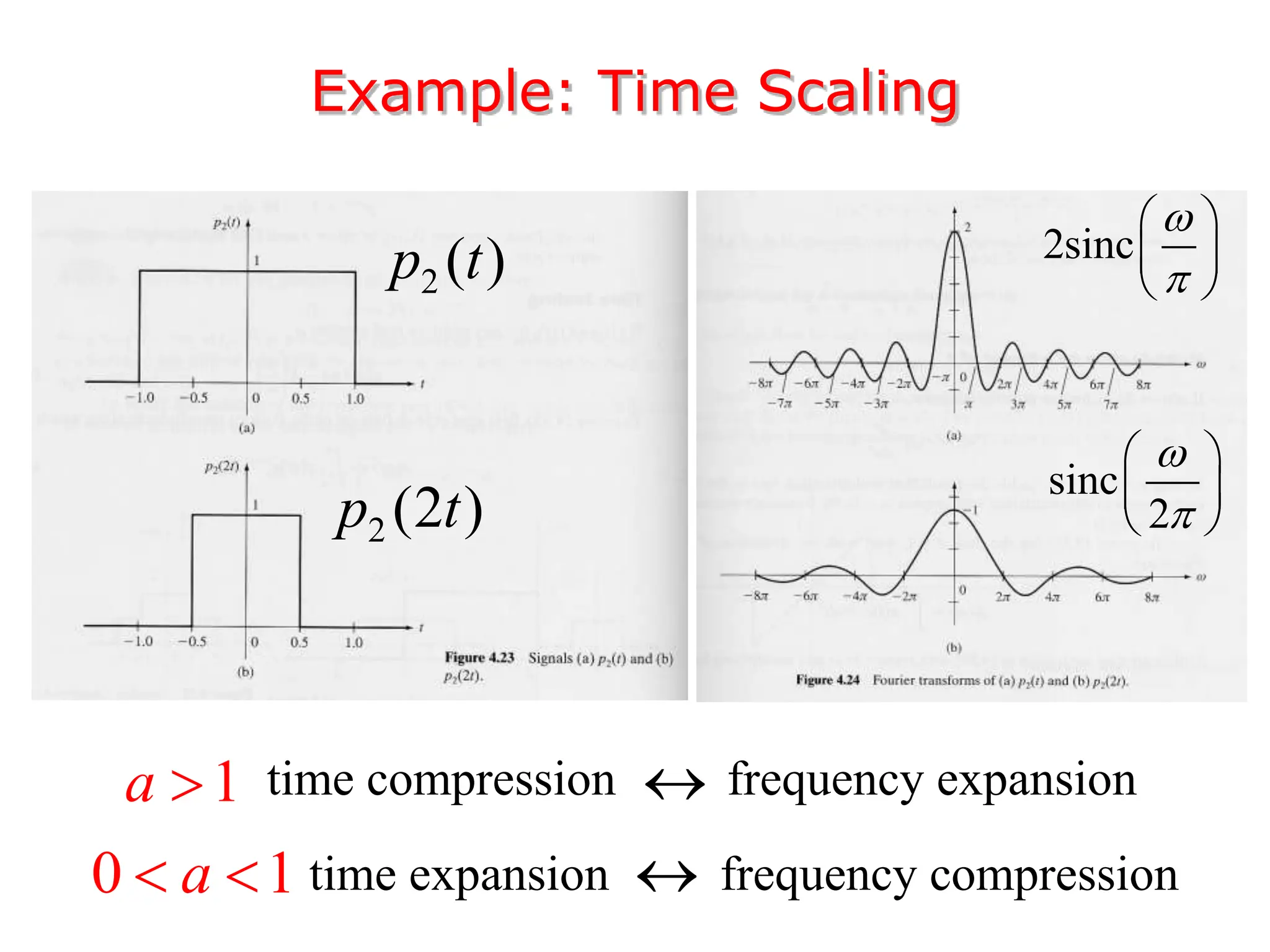

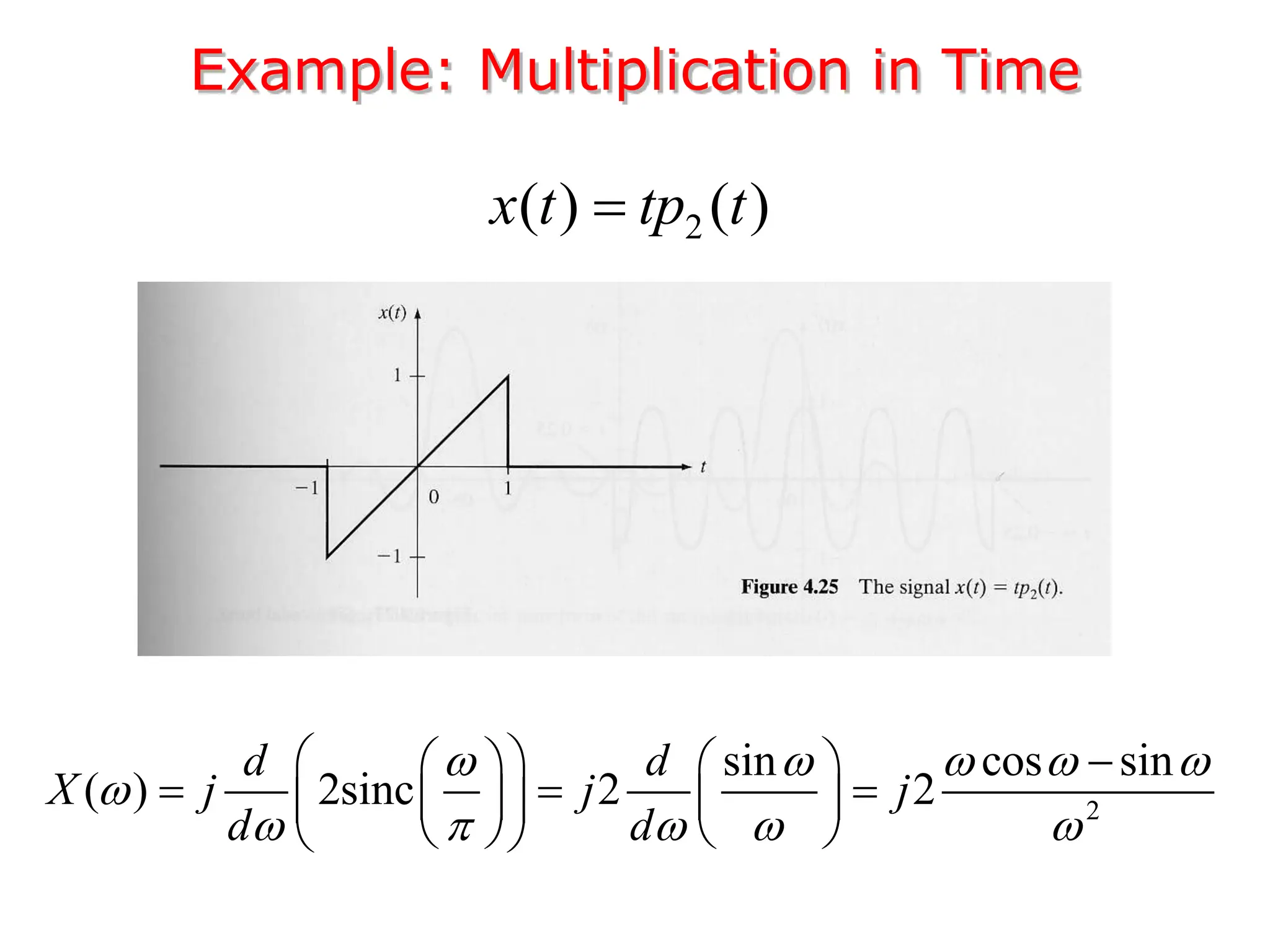

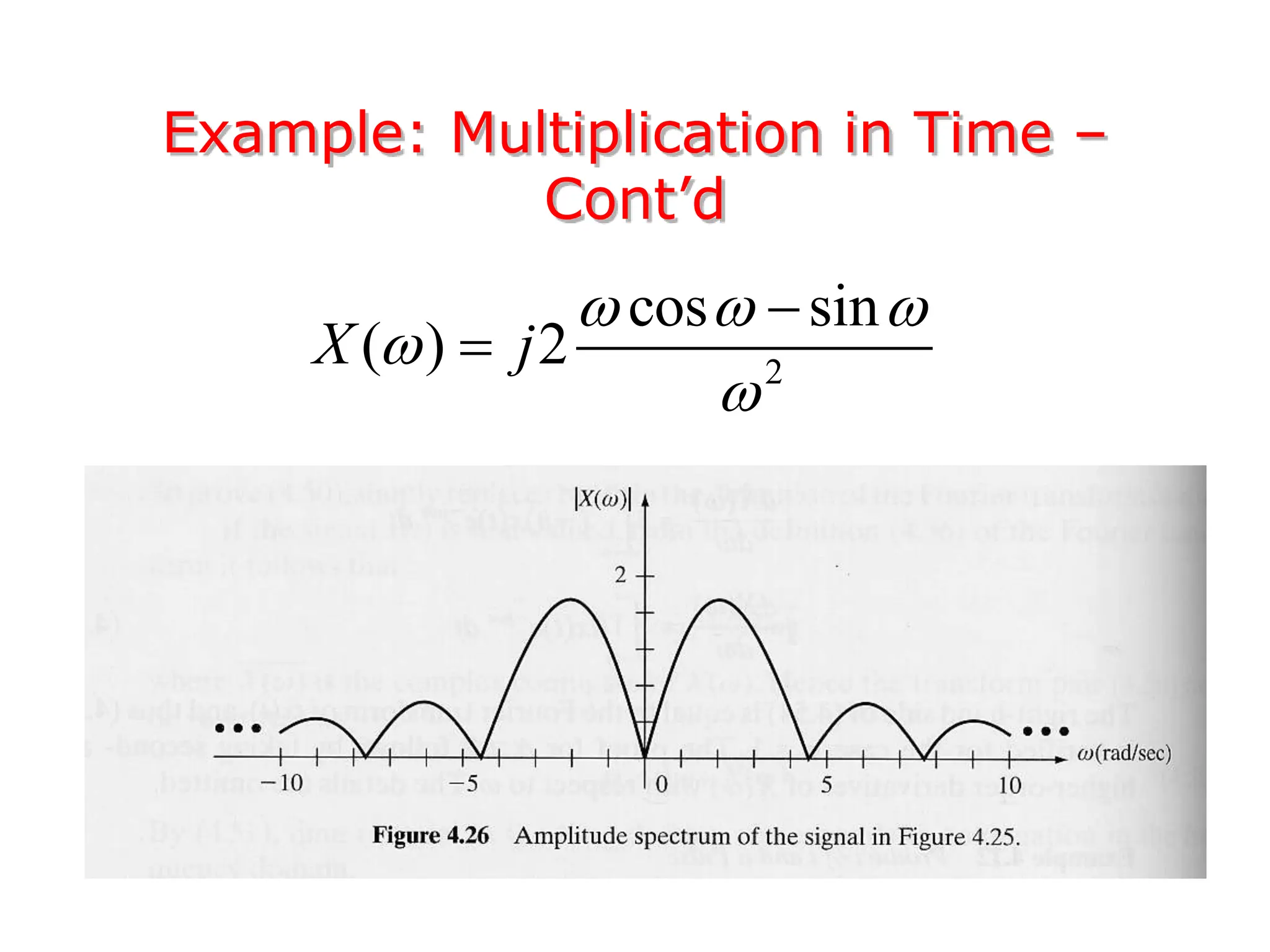

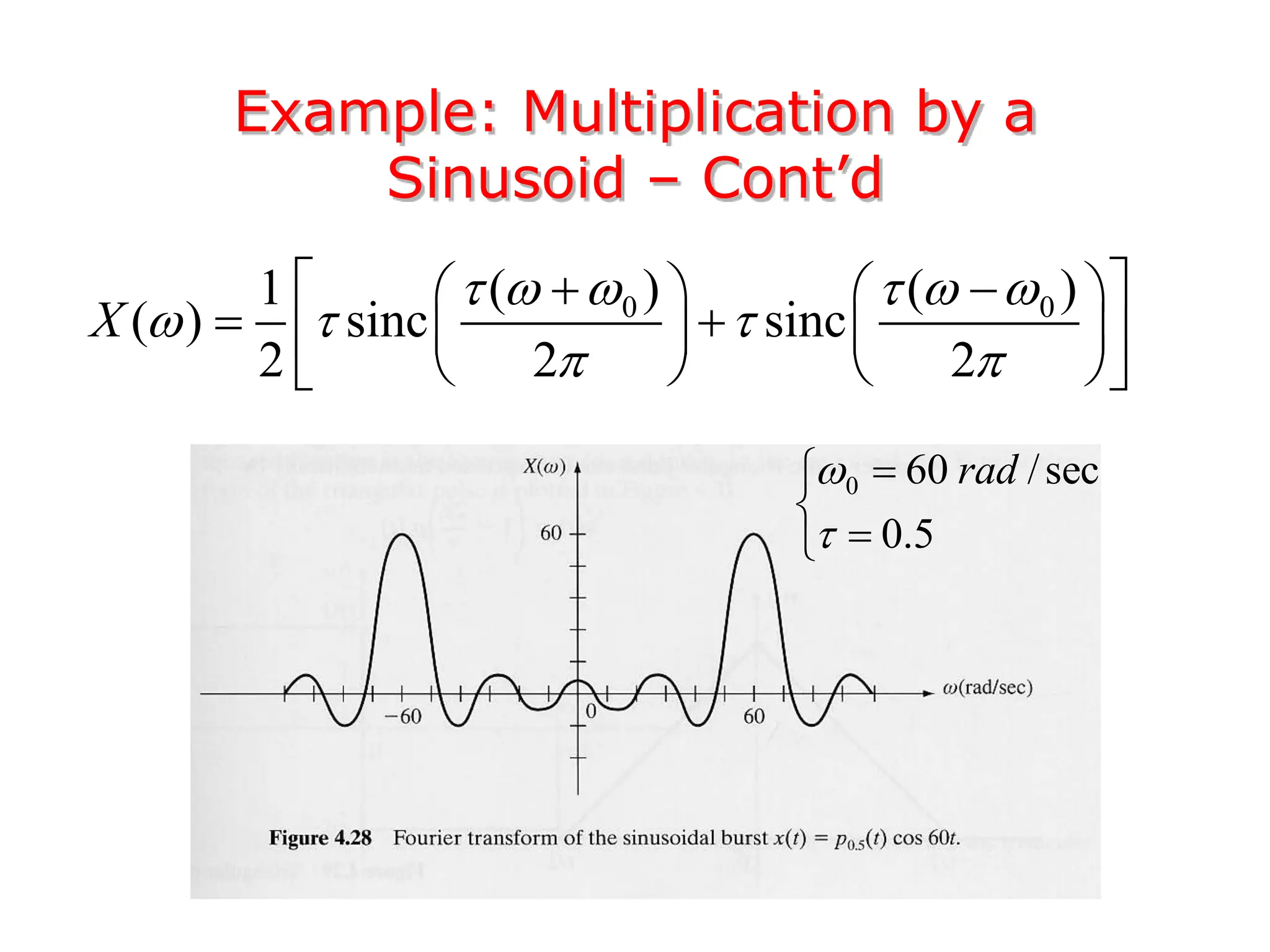

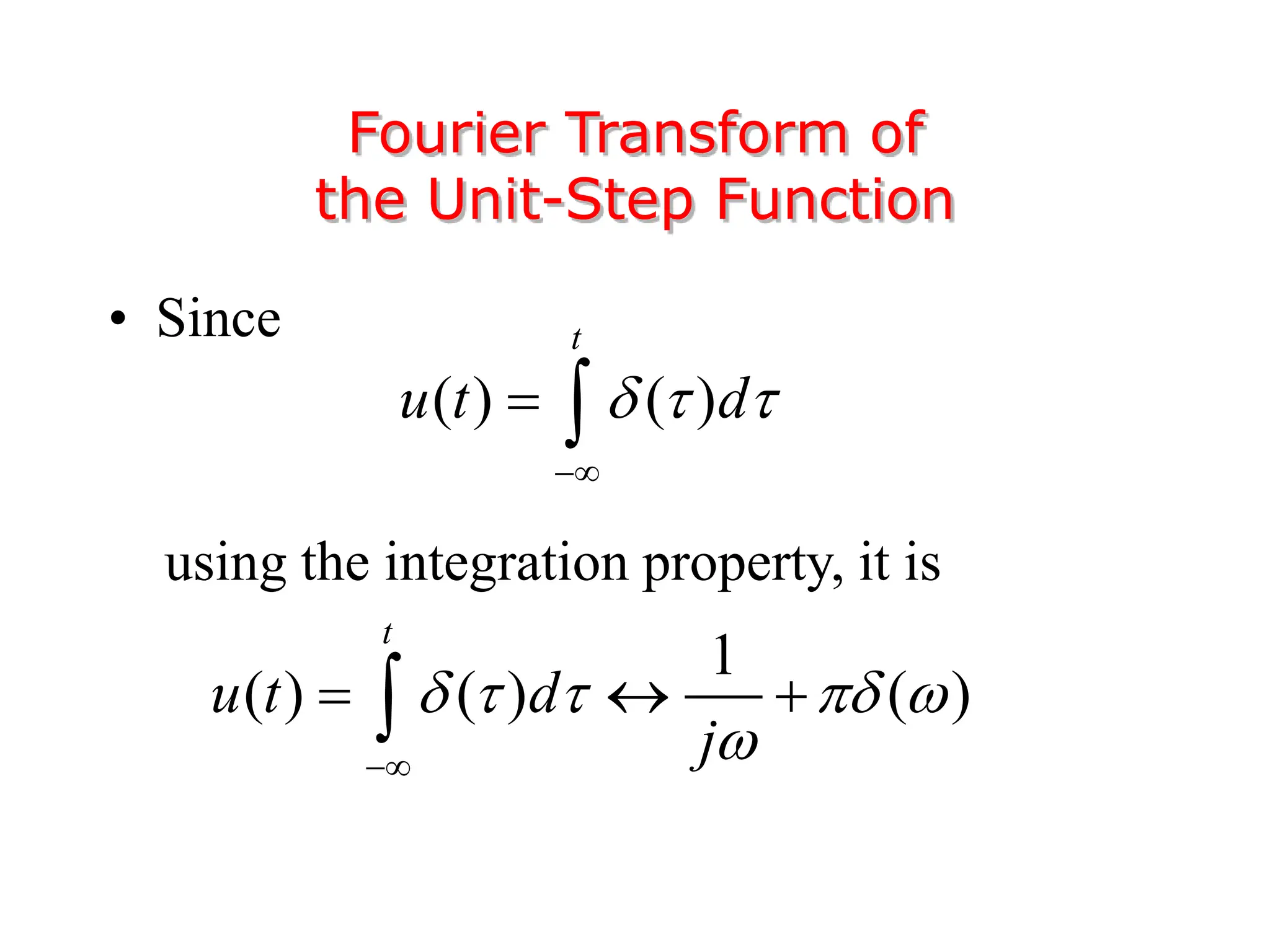

3. The Fourier transform allows representing aperiodic signals as a sum of sinusoids of all possible frequencies, resulting in a continuous spectrum rather than a discrete line spectrum. The Fourier transform of a rectangular pulse is a sinc function.