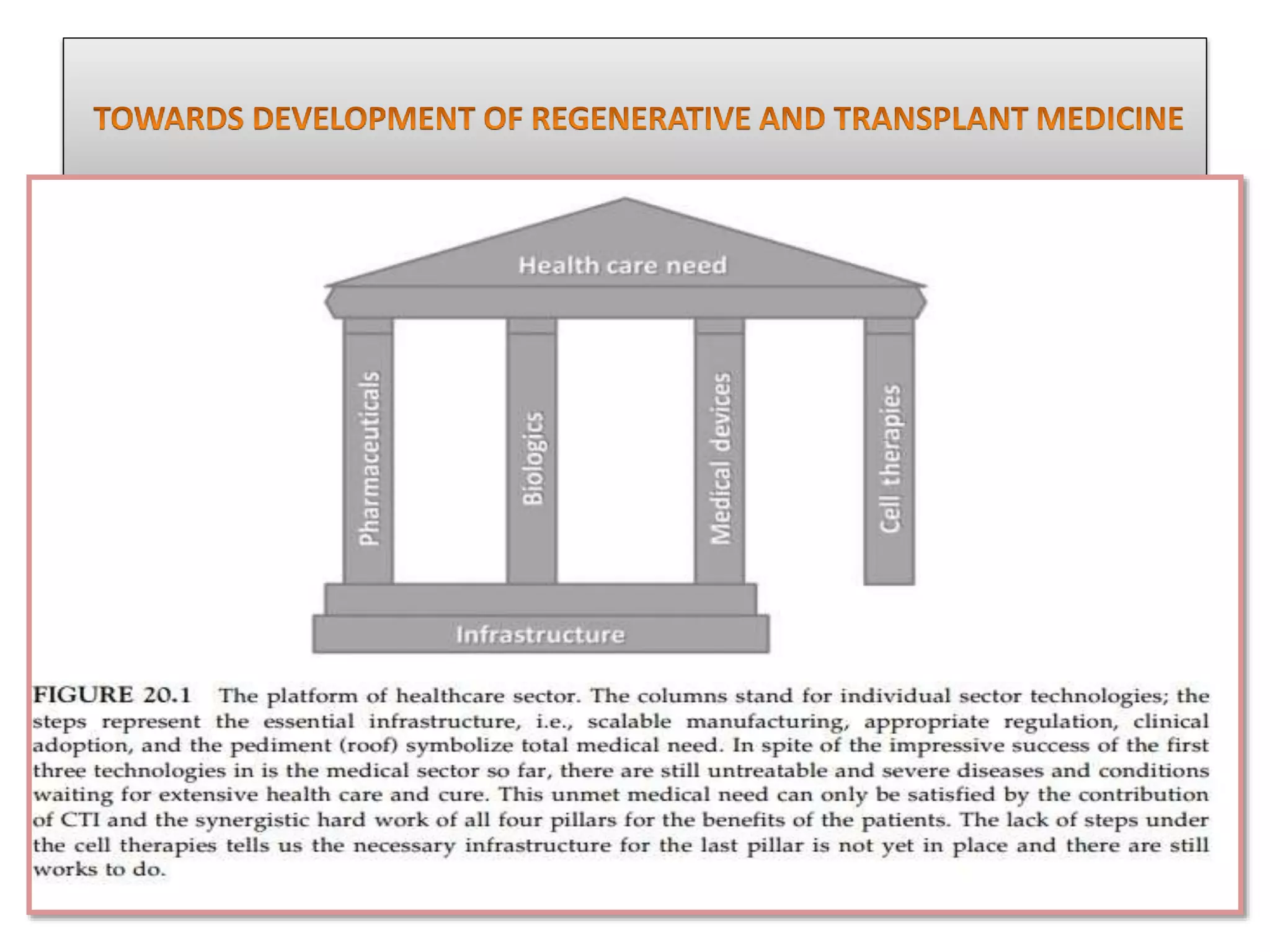

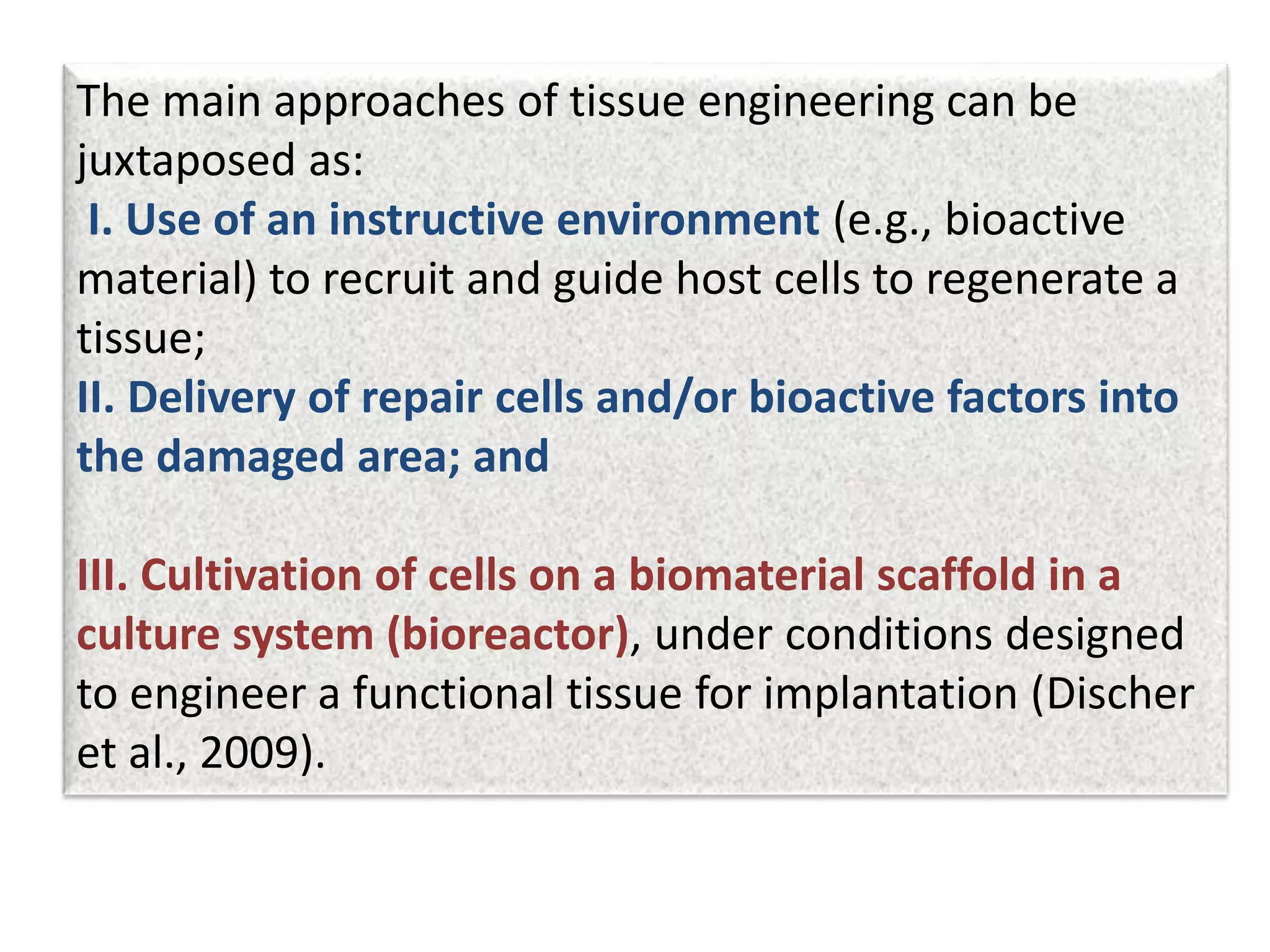

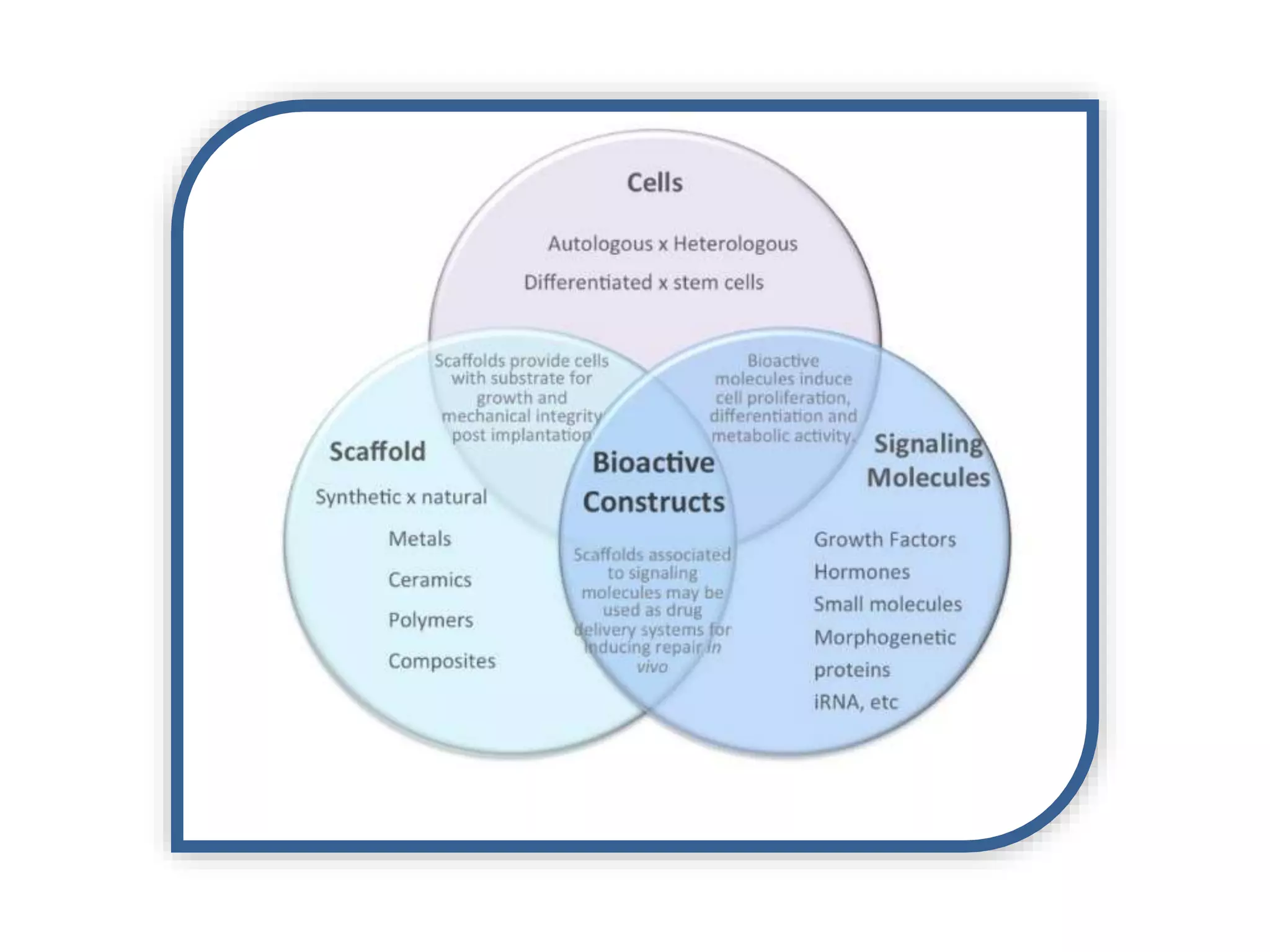

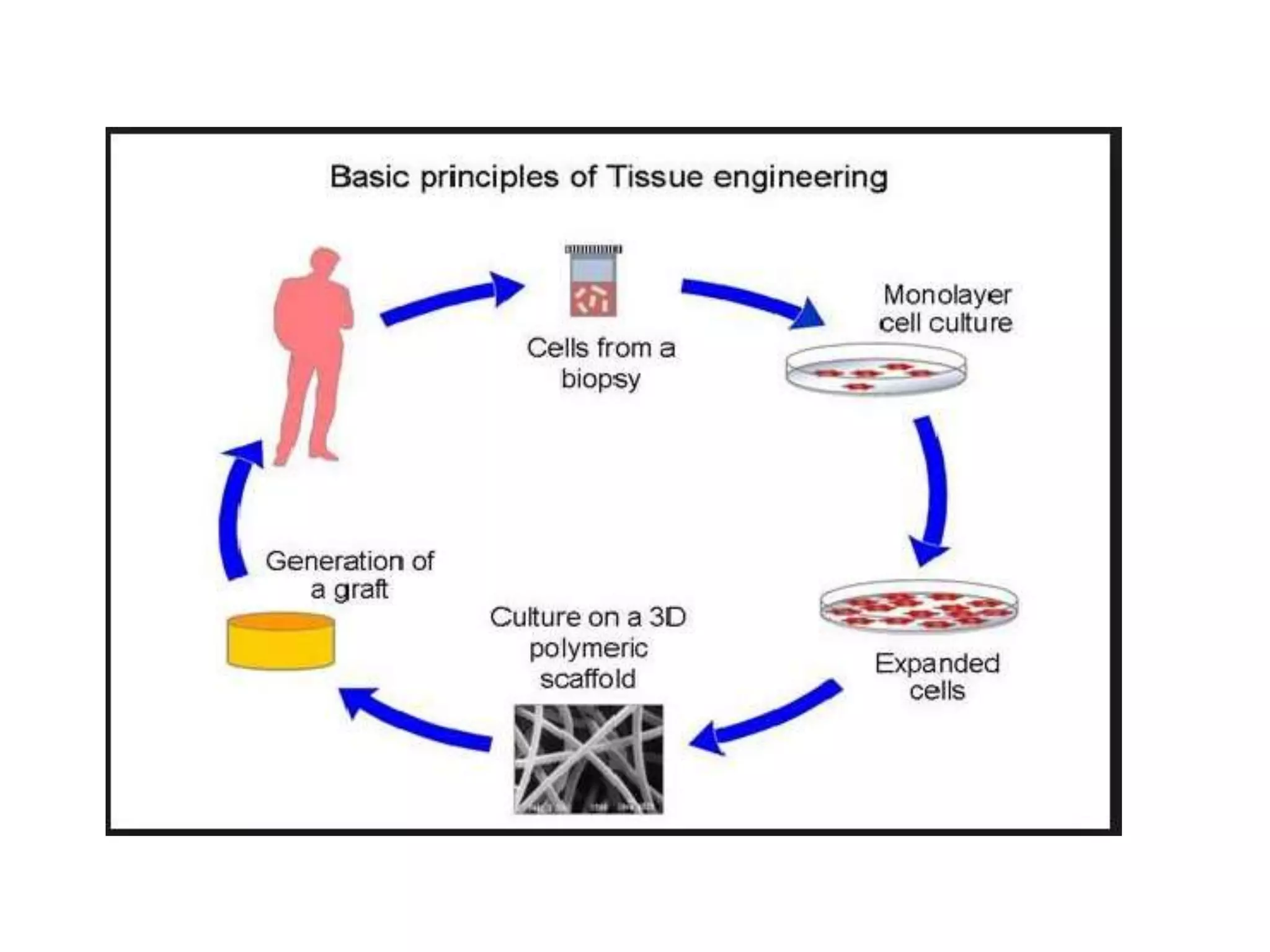

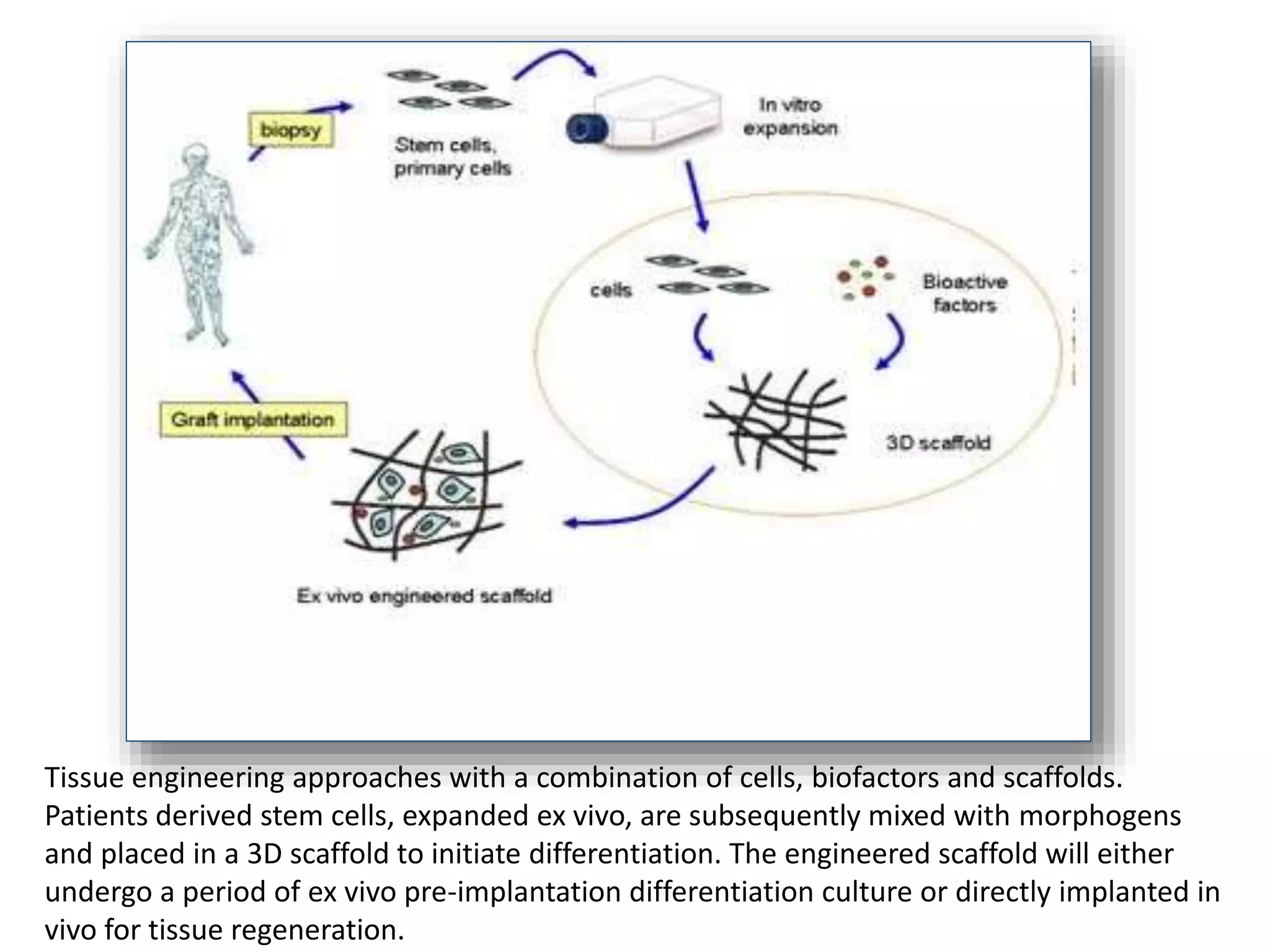

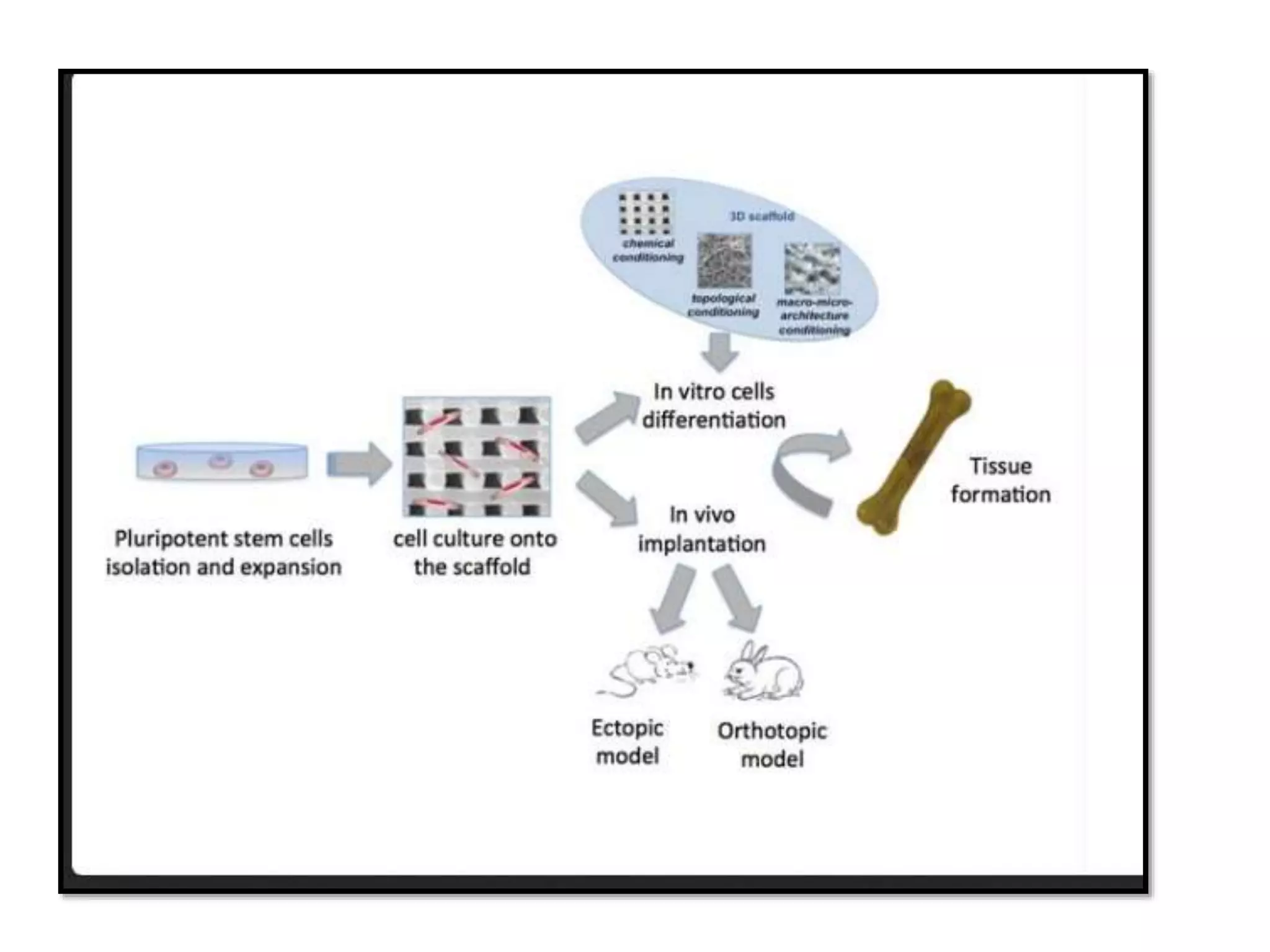

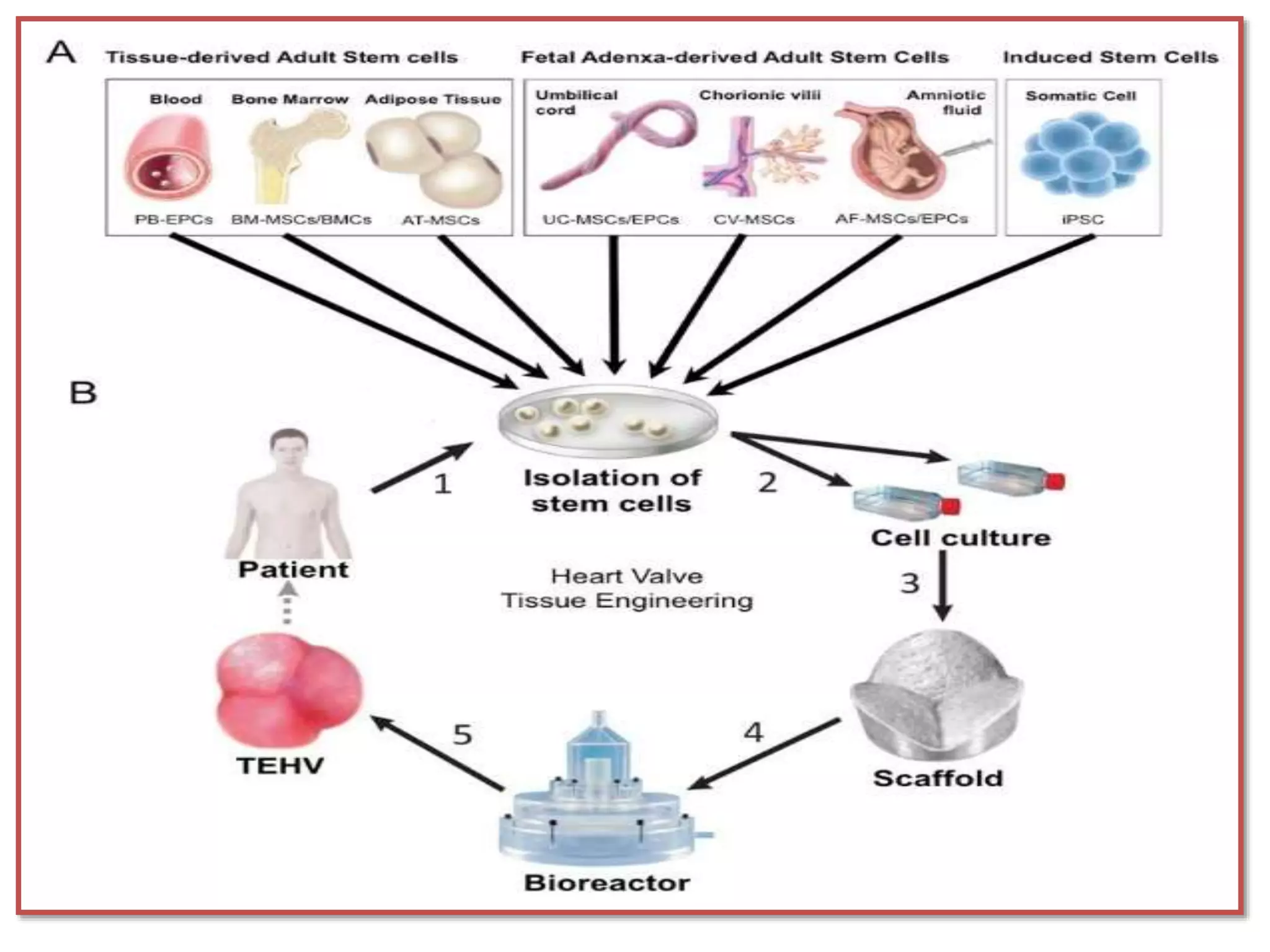

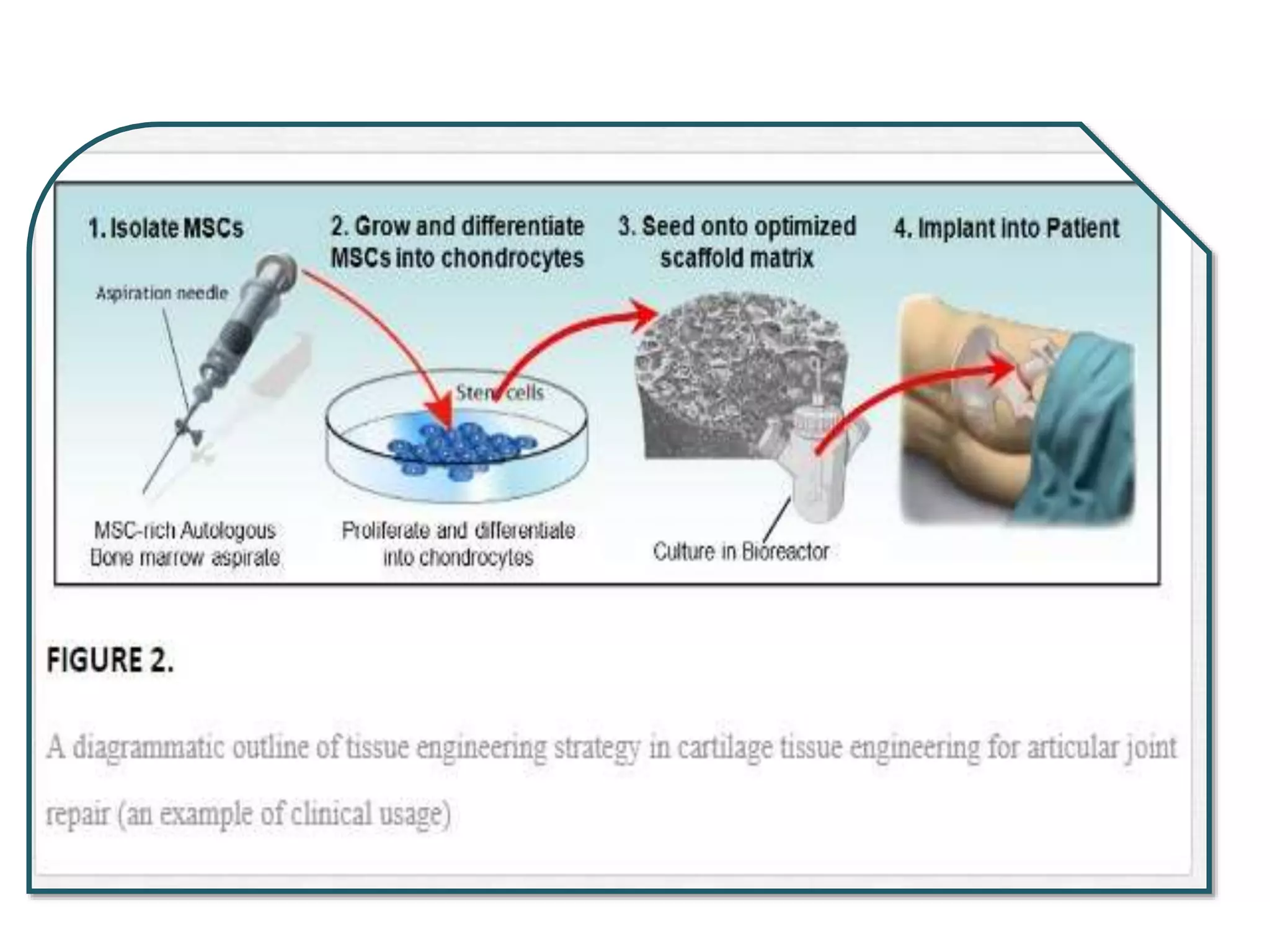

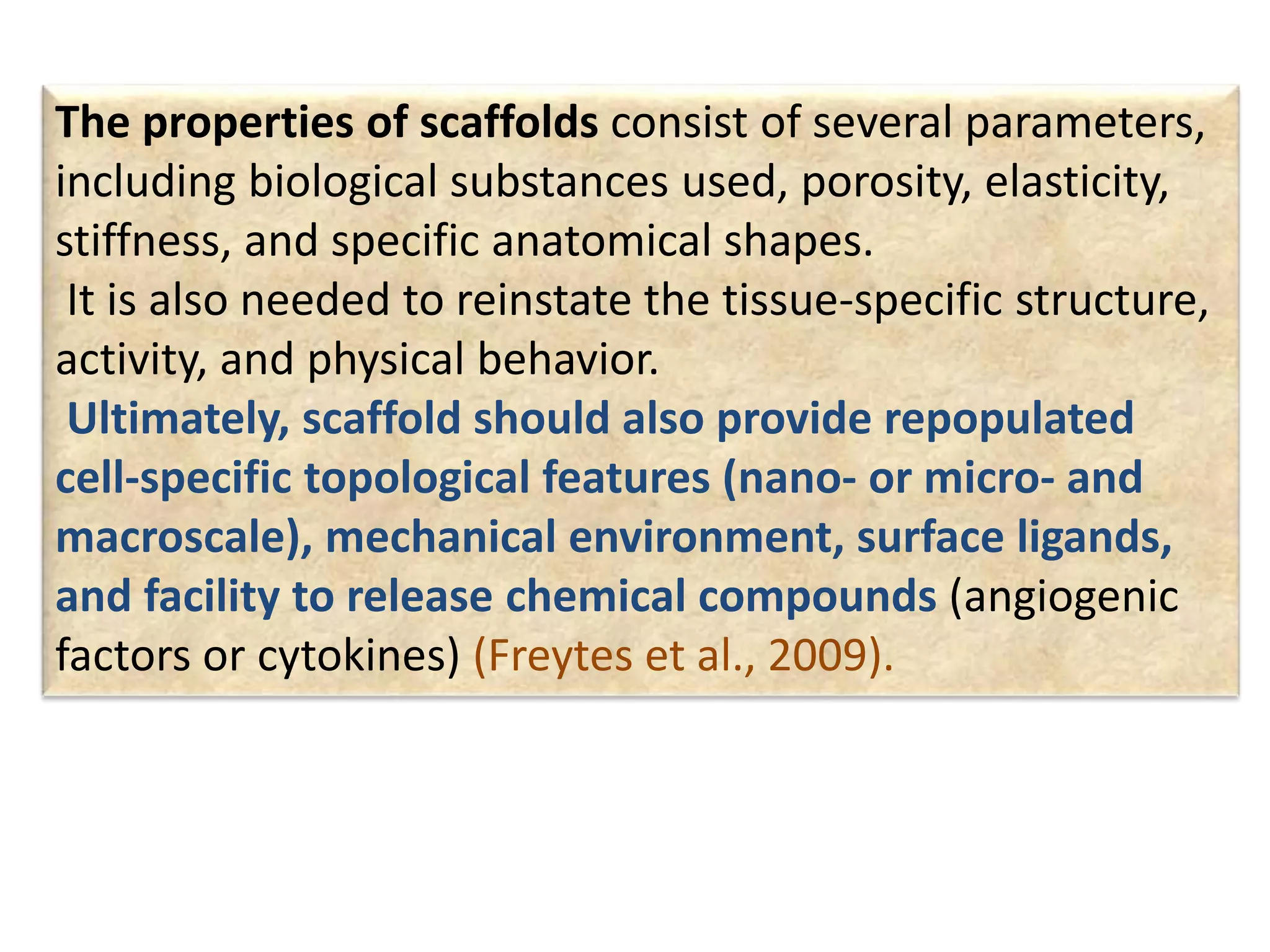

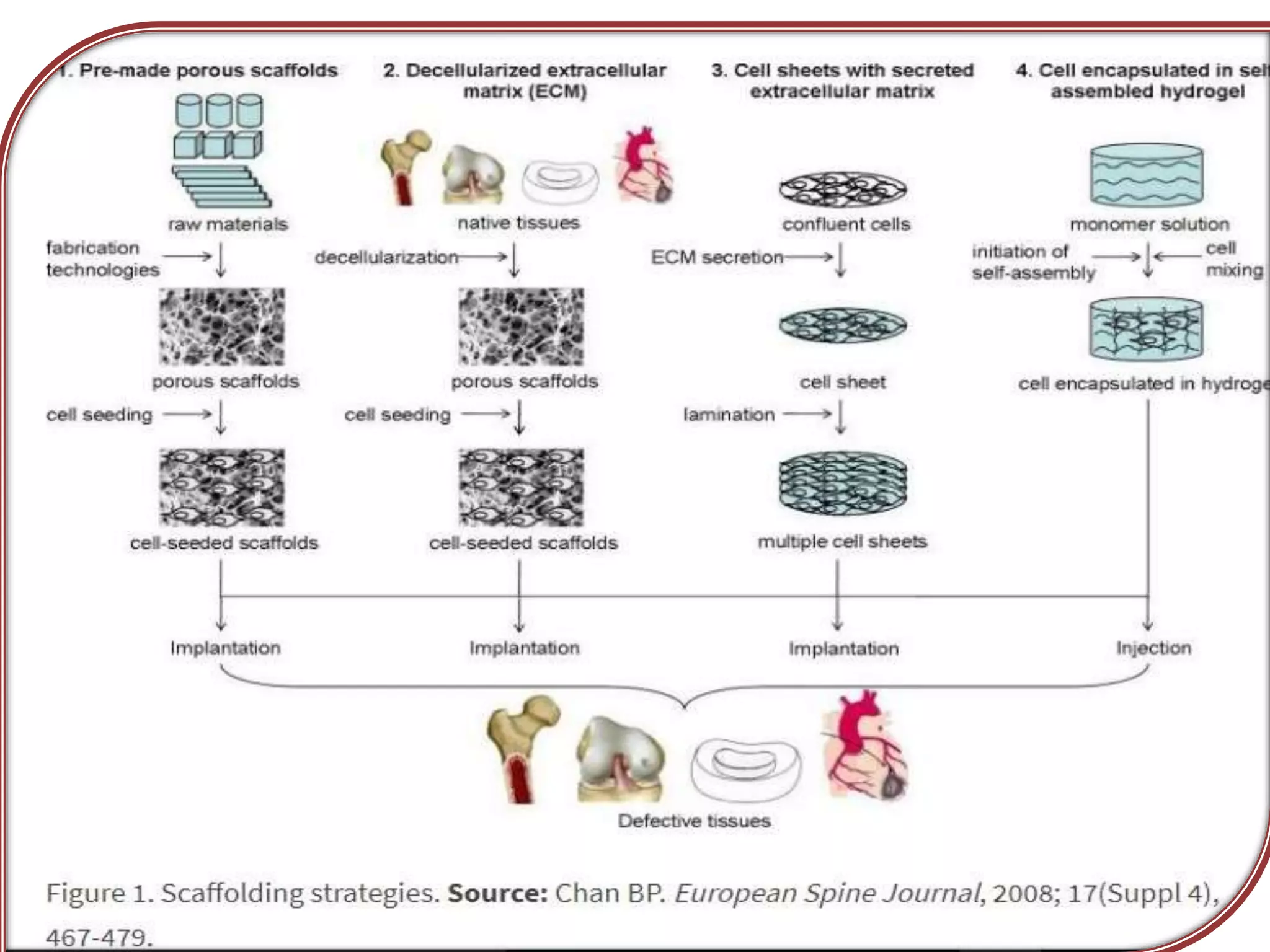

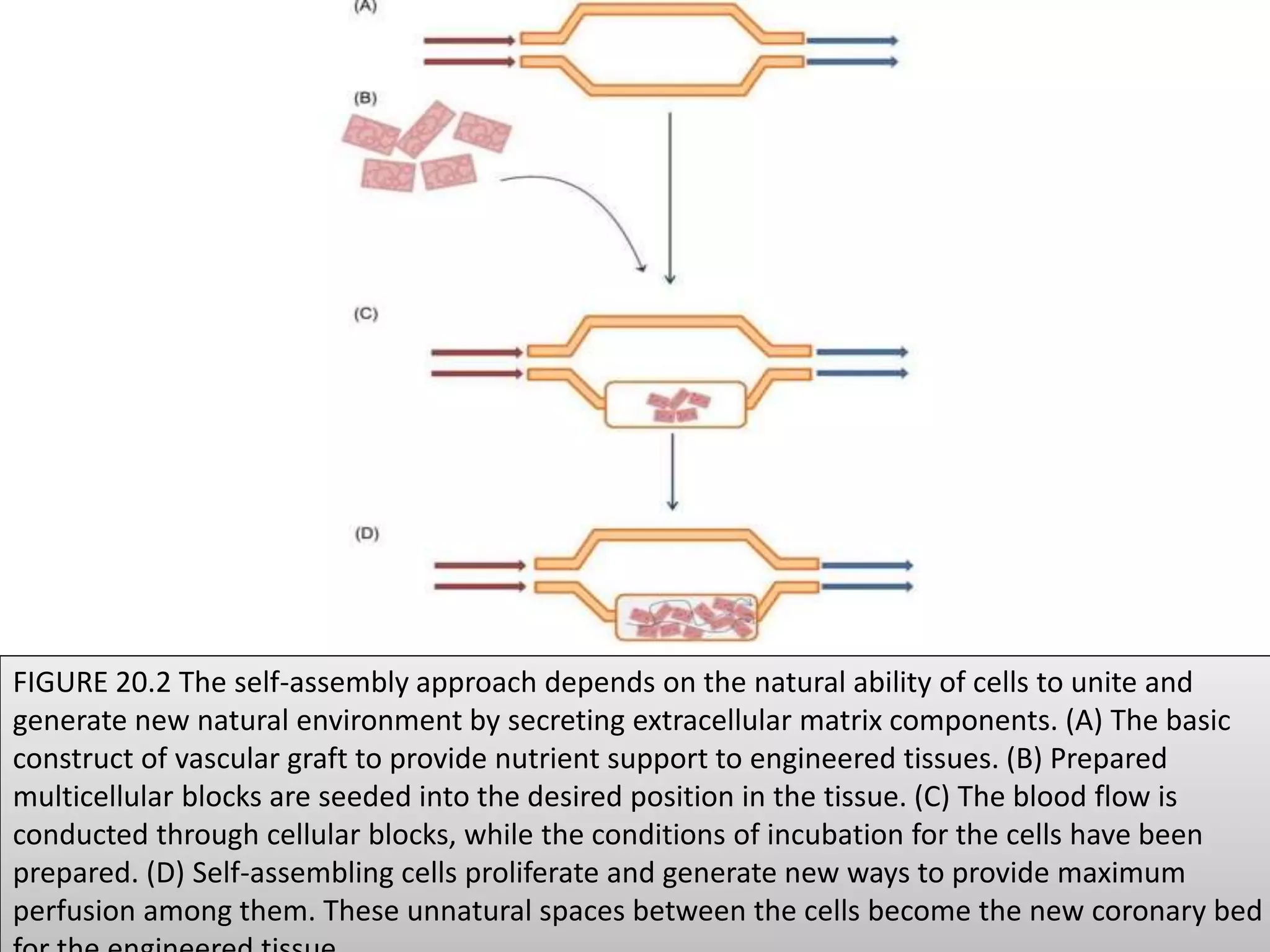

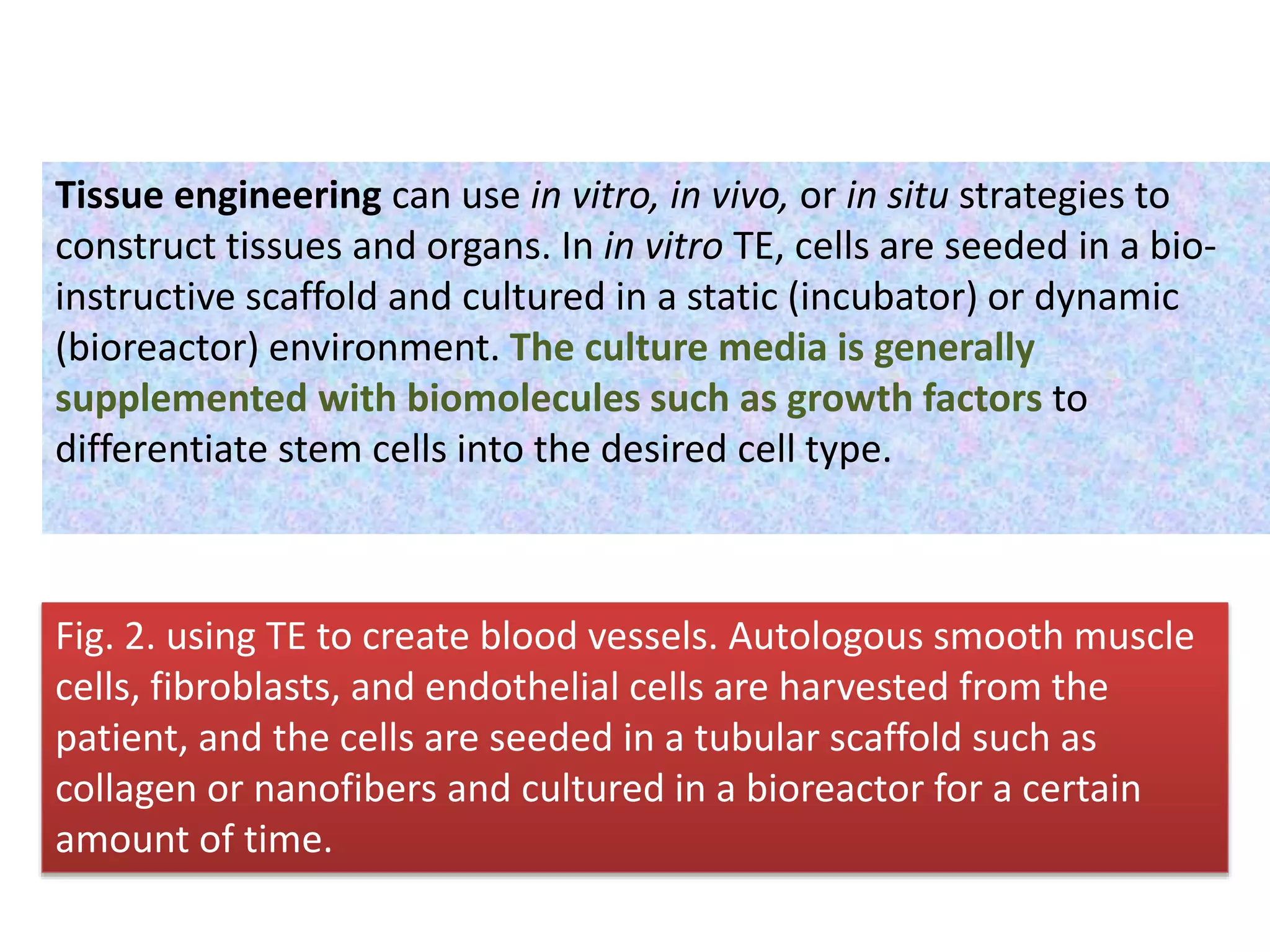

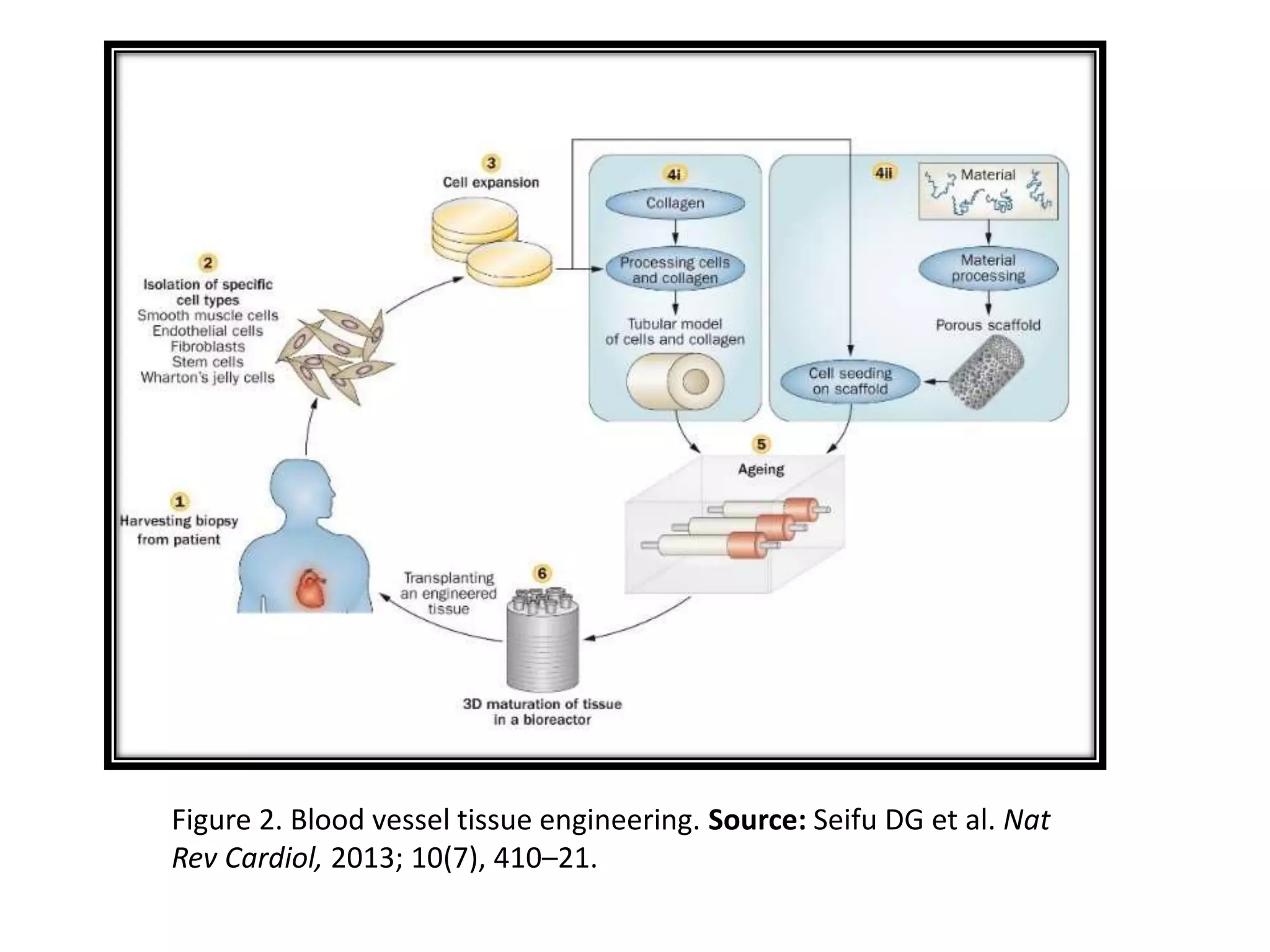

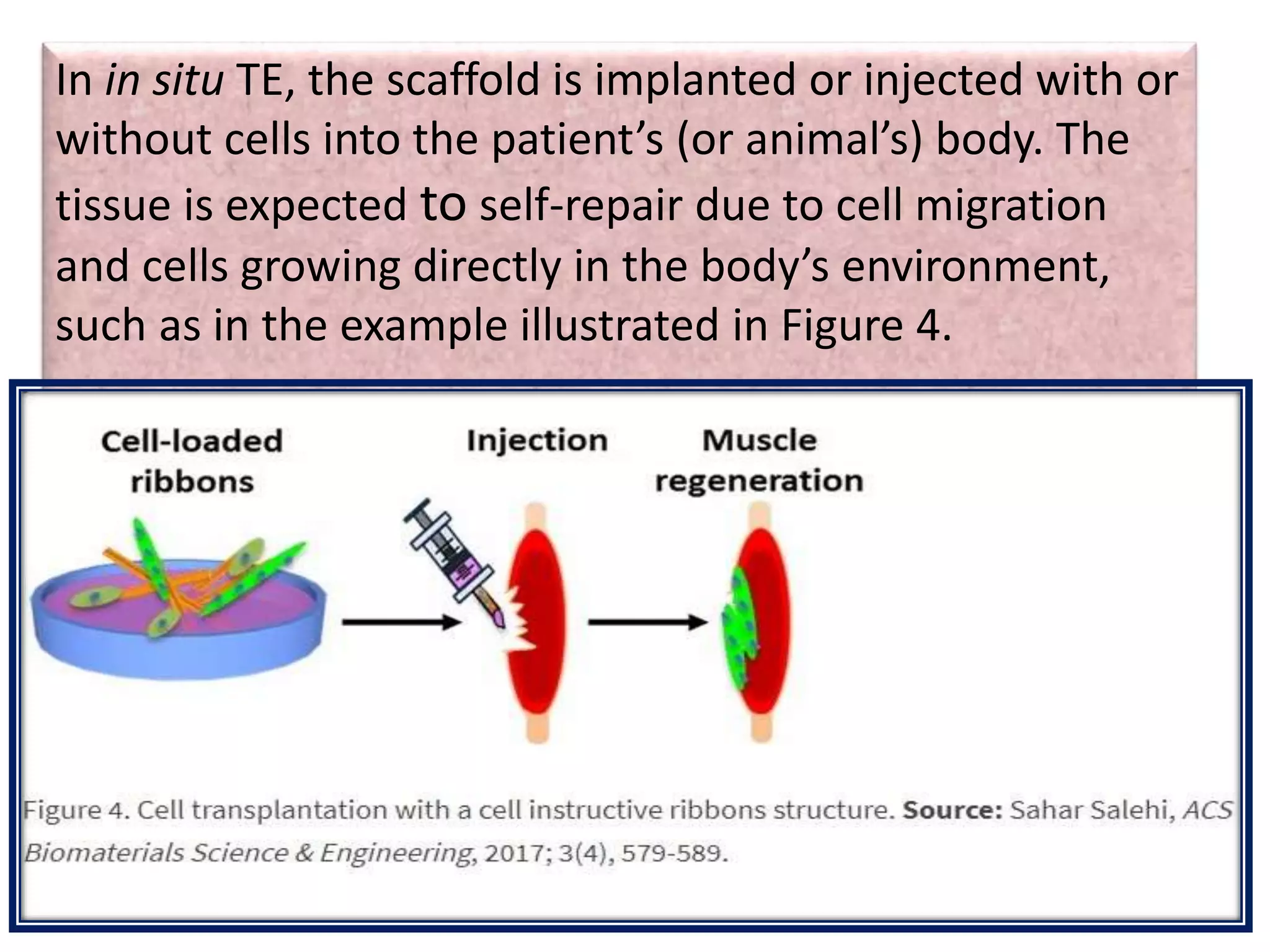

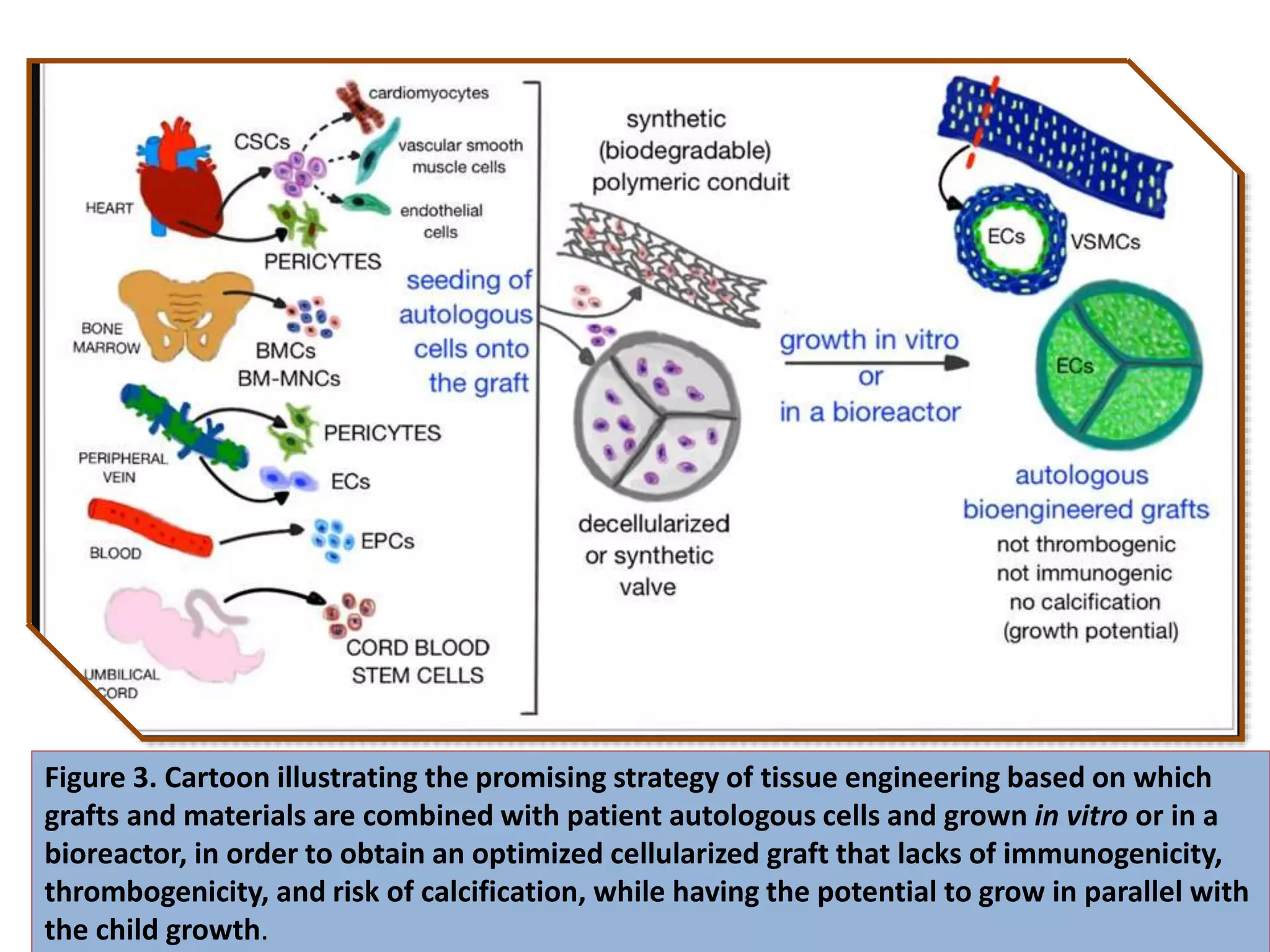

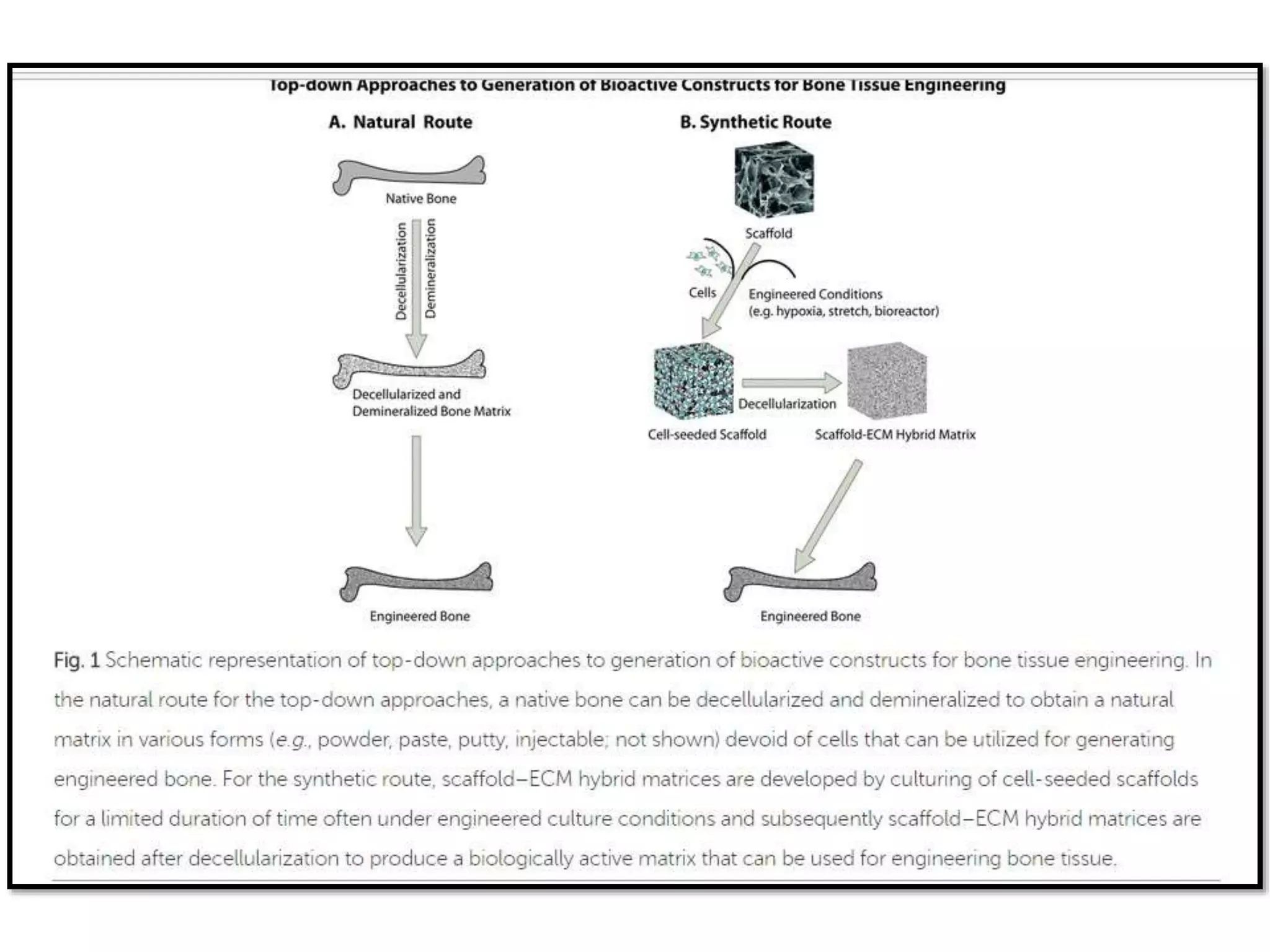

This document discusses tissue engineering approaches and cell sources. It defines tissue engineering as using cells, engineering, and materials to improve or replace biological functions. Tissue engineering offers opportunities like creating implants and studying stem cells. The main approaches are using instructive environments to guide regeneration, delivering cells/factors, and culturing cells on scaffolds. Sources of cells discussed include induced pluripotent stem cells, fetal/umbilical cord cells, and various adult cells like mesenchymal stem cells. Scaffolds are also discussed as a key element, with properties like porosity and factors released. Both in vitro and in vivo strategies can be used.

![Inkjet bioprinting, also referred as ‘drop-on-demand printers’

appeared early in 2003 [108]. Firstly developed inkjet printers

modified commercially available two-dimensional (2D) ink-

based printers by replacing the ink in the cartridge by a

biological material, and the paper, by an electric-controlled

elevator that moves on the z direction providing three-

dimensionality (reviewed in [12]) [109]. Nowadays, inkjet

printers make use of nozzles that generate isolated droplets of

cell-laden material by means of piezoelectric [110] or thermal

(reviewed in [111])

R.S. Tuan, G. 5 (2003), J.P. Mattimore, et al.( 2010) Y.

Fang, et al. (2012)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftofficepowerpointpresentation-180822210541/75/Bio-engineering-55-2048.jpg)

![Fig. 2. Illustration of various features of polymer important from bioprinting perspective: (a)

hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties, (b) cross-linking potential, (c) viscosity,(d)

mechanical features, (e) cell adhesion and biocompatibility, and (f) biodegradation

ability.The figure has been reproduced from [20] with permission from Academic Press.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftofficepowerpointpresentation-180822210541/75/Bio-engineering-62-2048.jpg)

![Fig. 4. Fabrication of aligned conductive polyaniline PANI/PLGA nanofibrous mesh, cell

seeding, electrical stimulation and the mechanisms of the synchronous cell beatings.

Reproduced with copyright permission from Ref. [168].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftofficepowerpointpresentation-180822210541/75/Bio-engineering-77-2048.jpg)