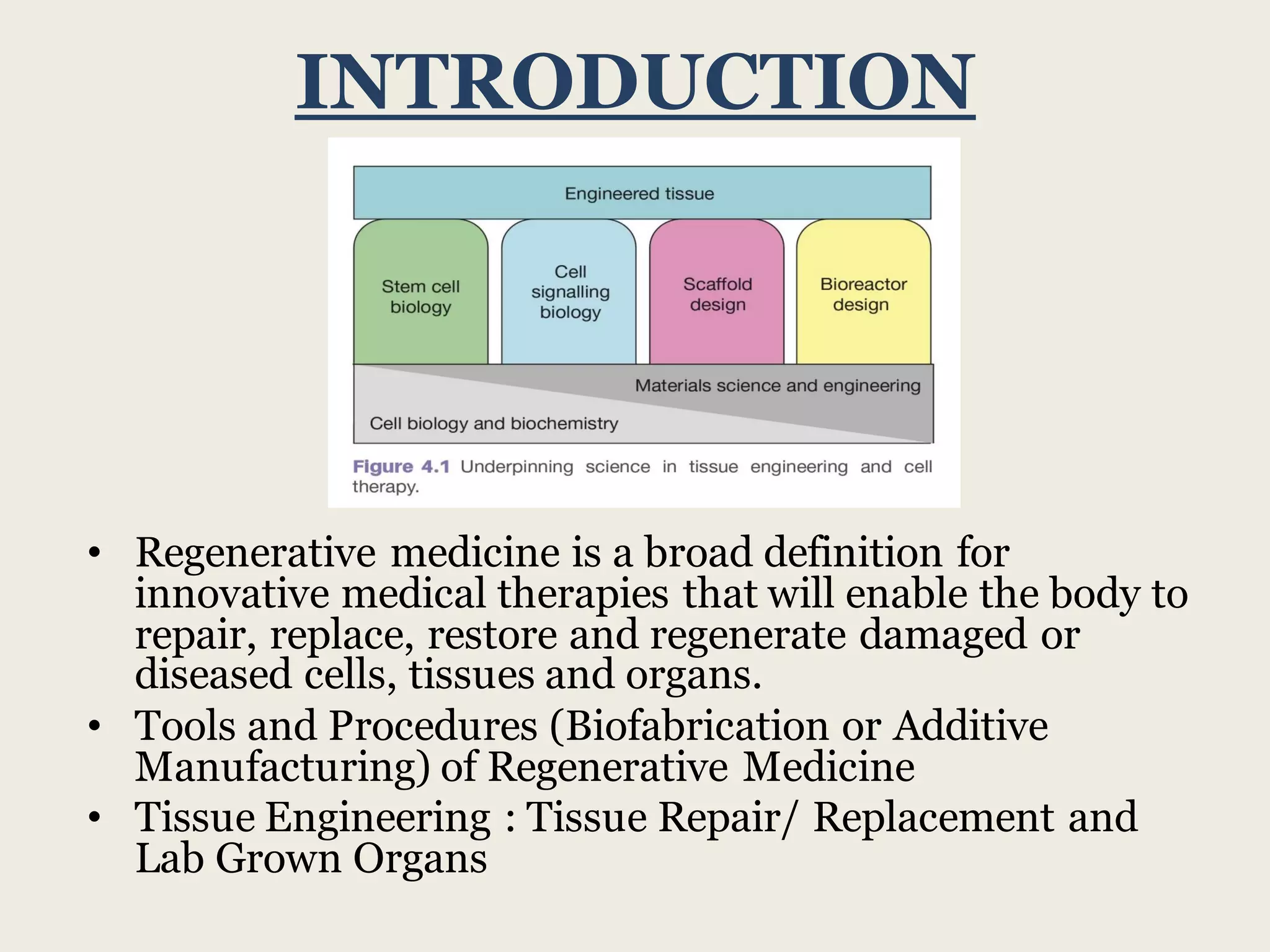

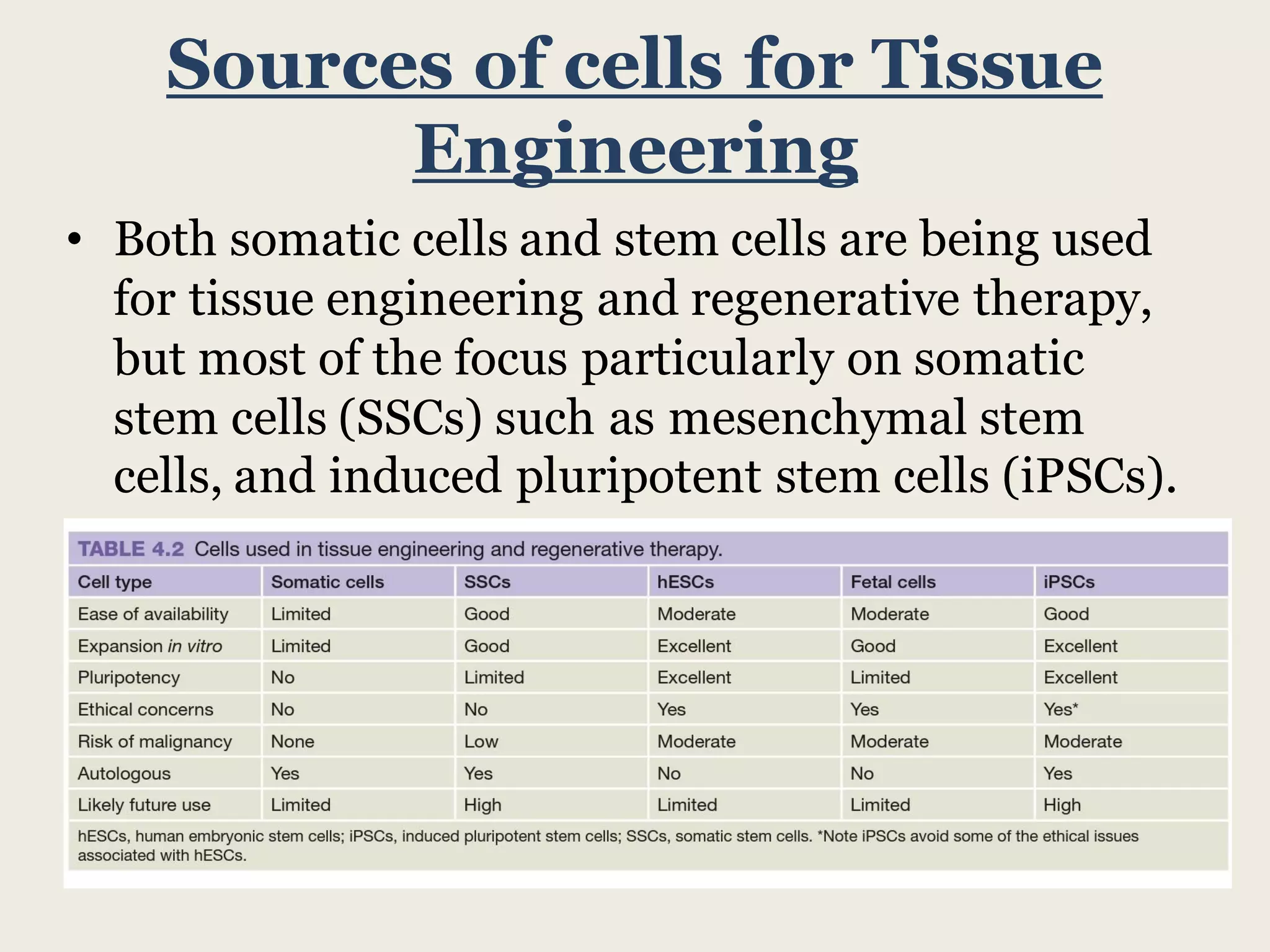

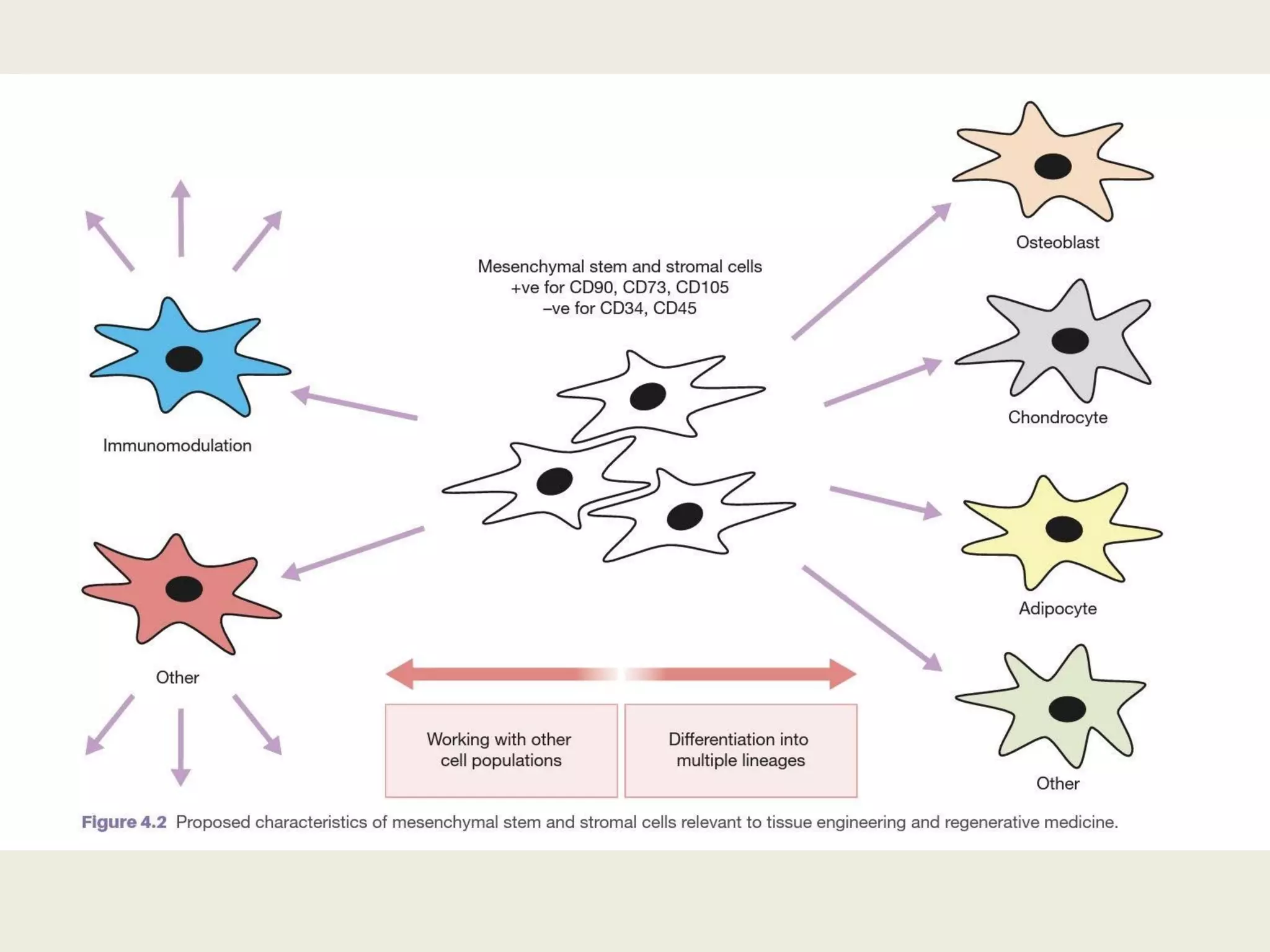

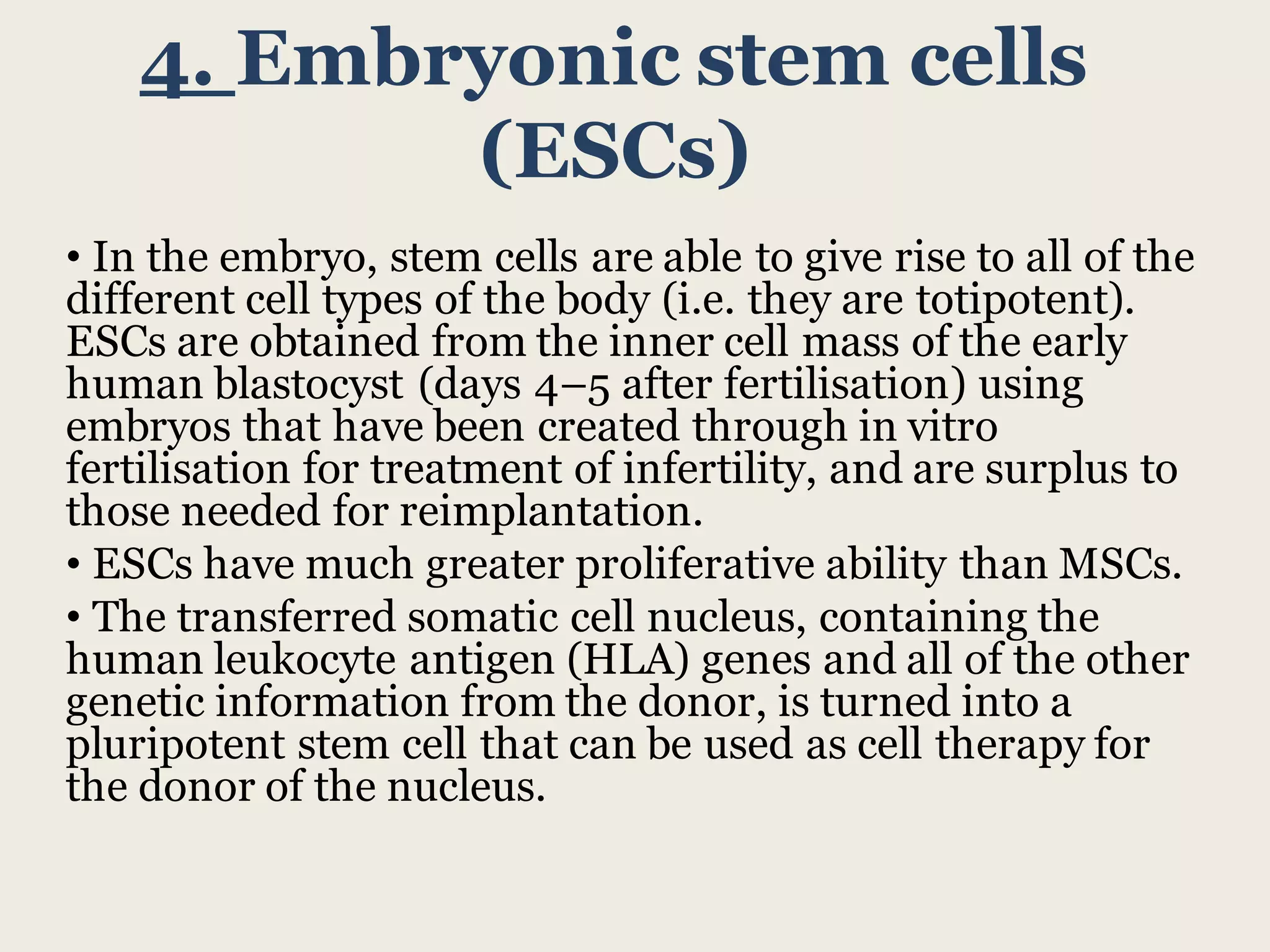

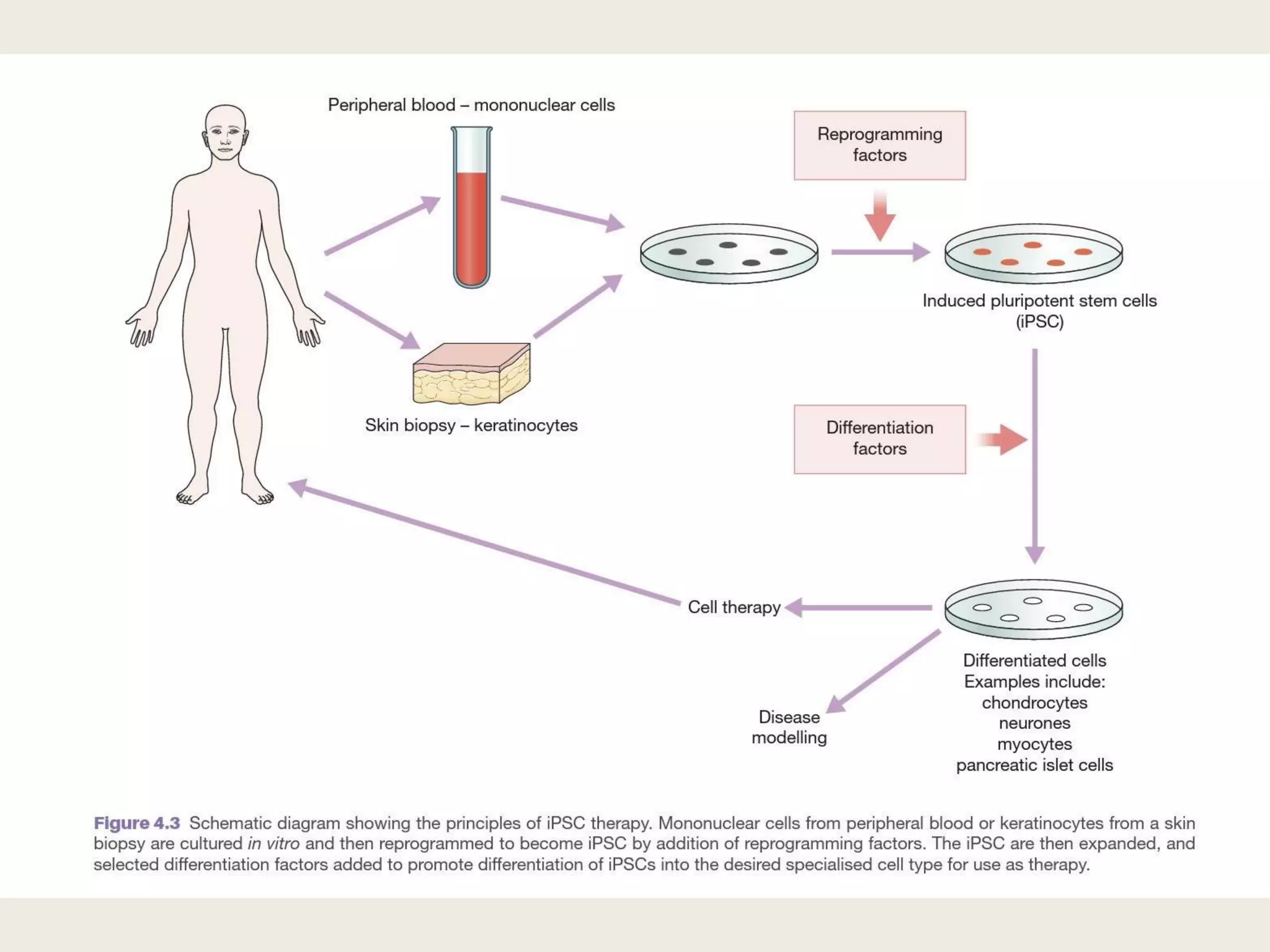

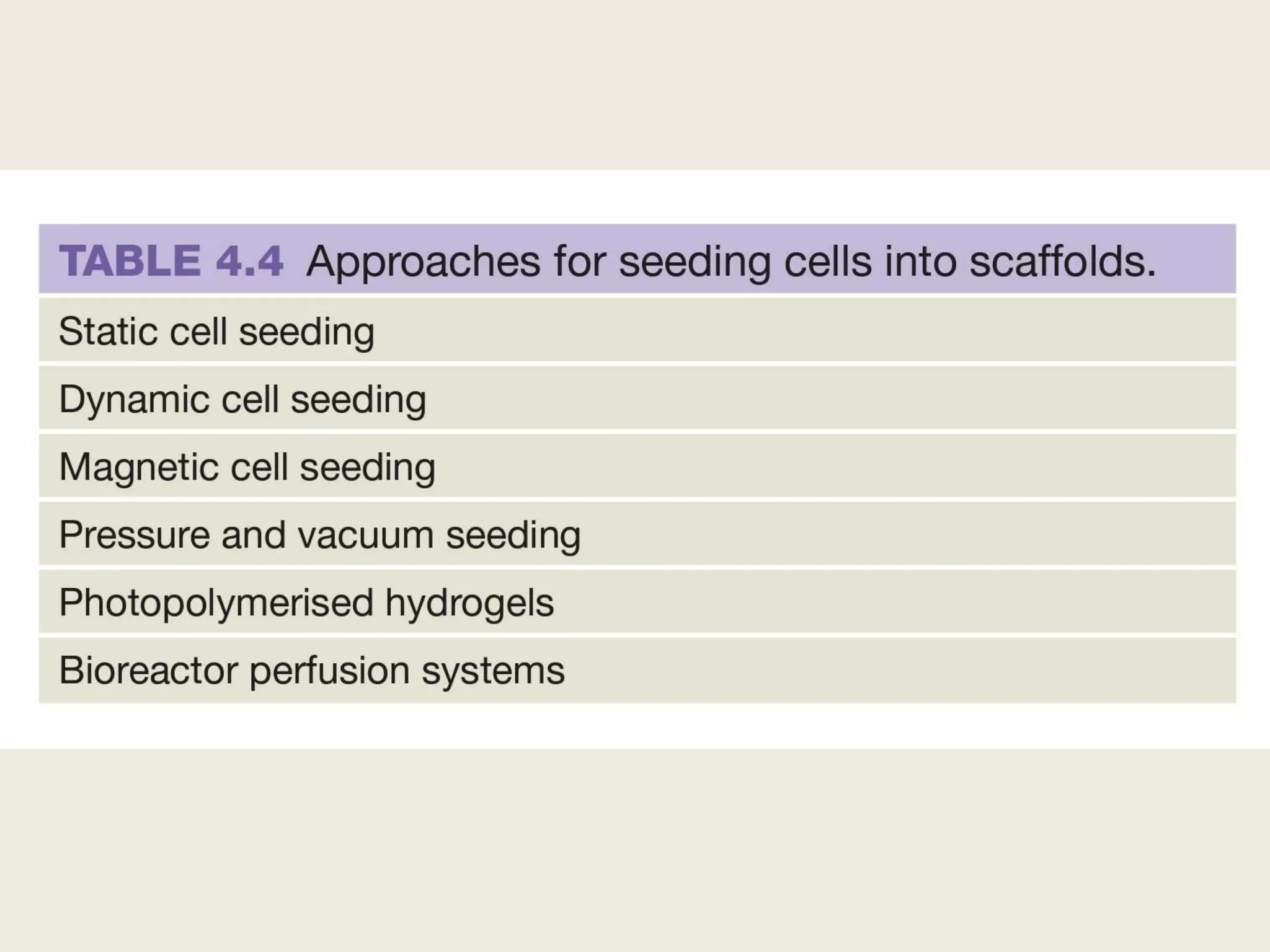

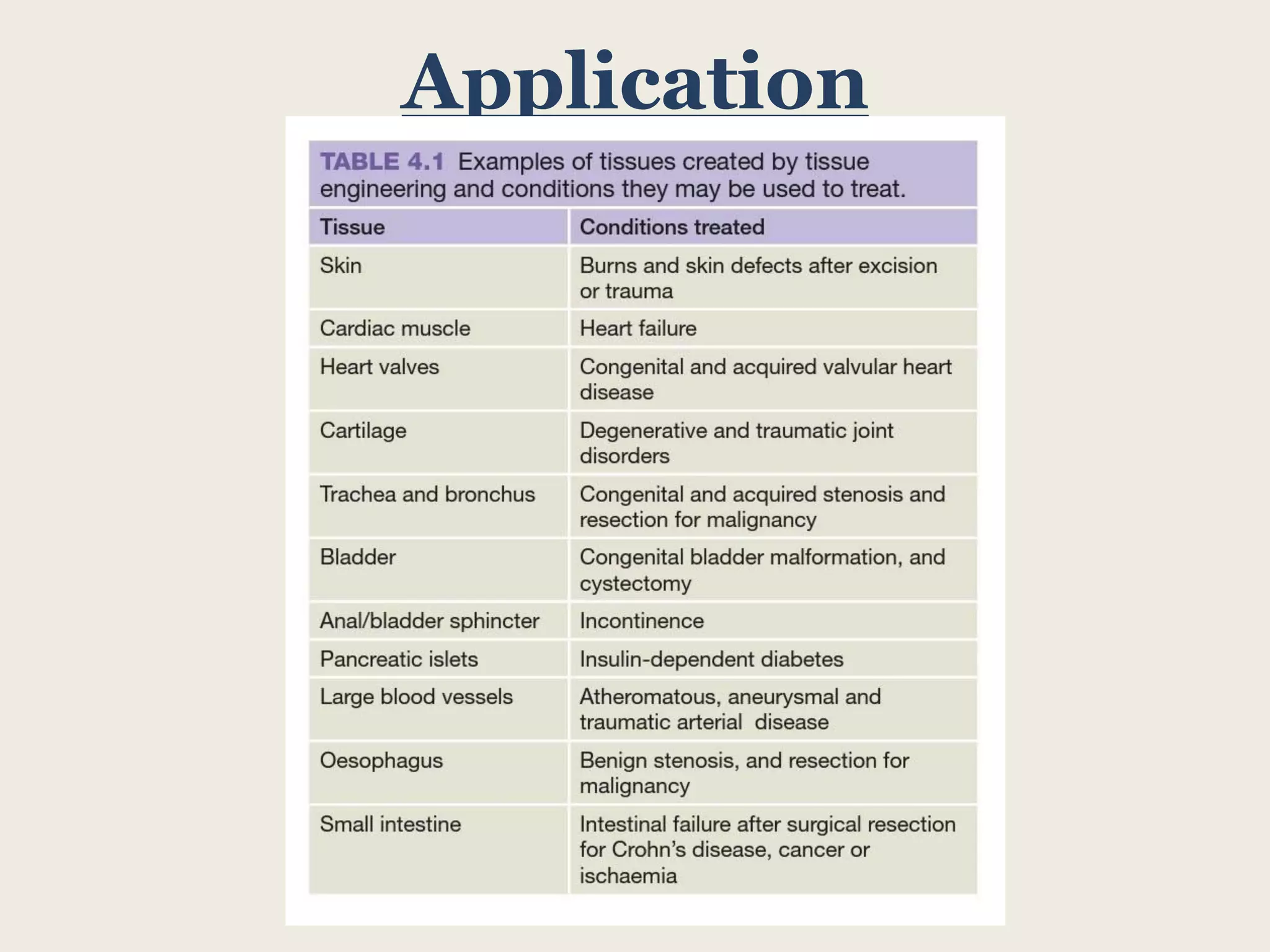

This document summarizes tissue engineering and regeneration. It discusses sources of cells for tissue engineering including stem cells, somatic stem cells like mesenchymal stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells. It also discusses scaffolds for tissue engineering, both natural scaffolds derived from tissues and artificial scaffolds made from polymers or ceramics. The challenges of engineering tissues in vitro include delivering nutrients to 3D constructs, maintaining cell viability, and ensuring cell function is maintained. Safety concerns include tumor formation and transmitting infections. The future of the field involves using stem and iPS cells with improved scaffolds, and tailoring therapies to patient subgroups through molecular profiling.