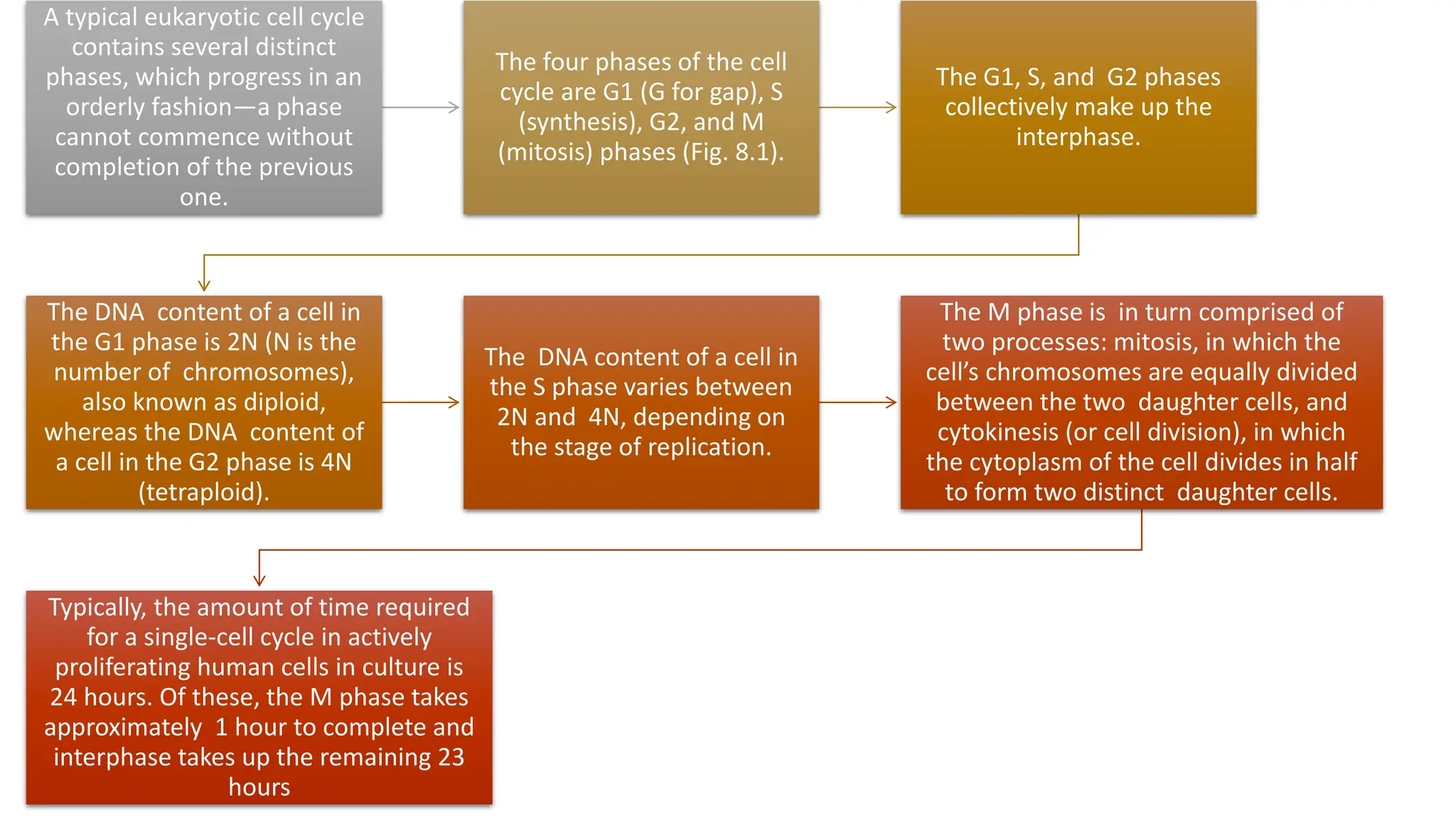

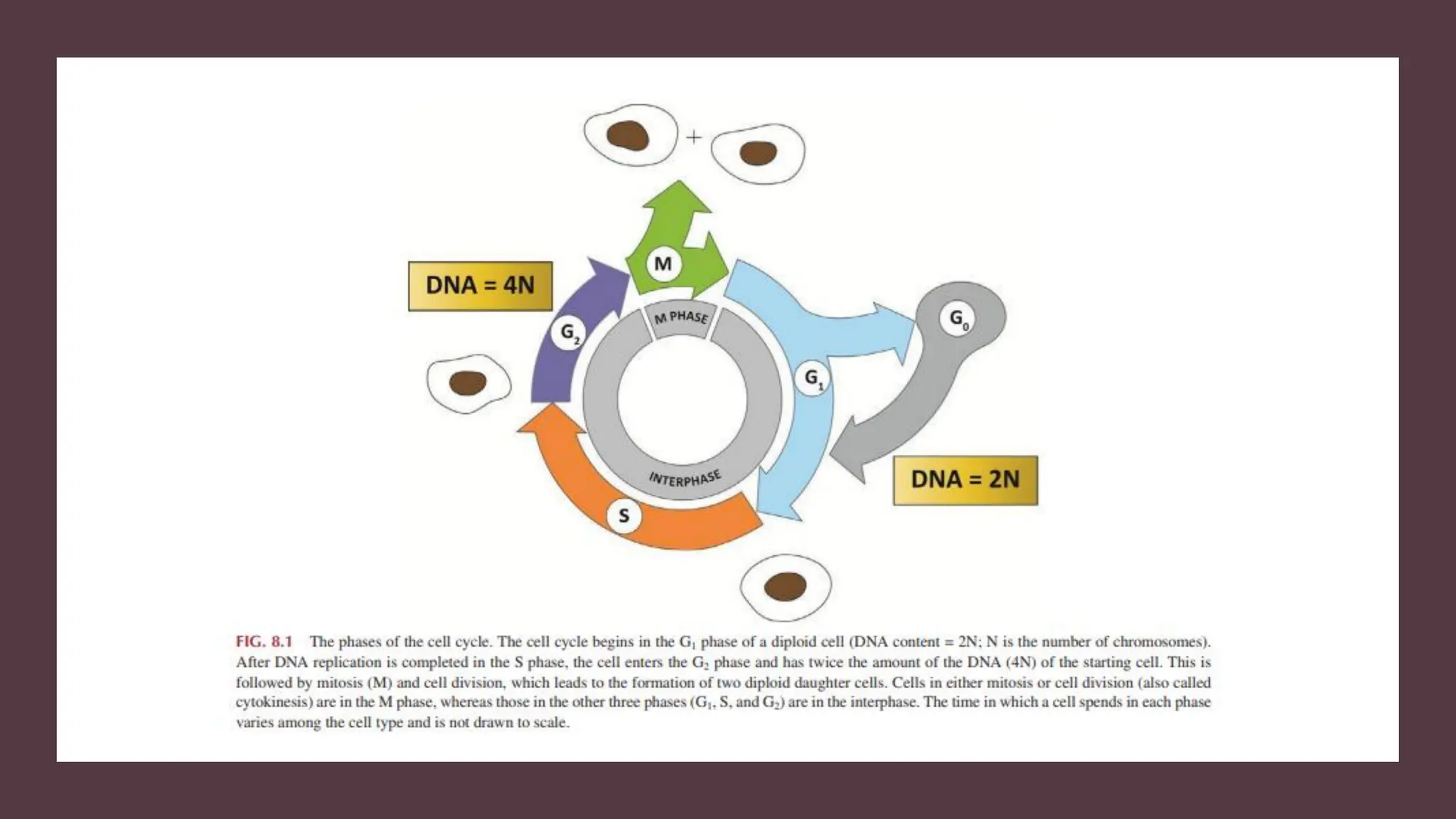

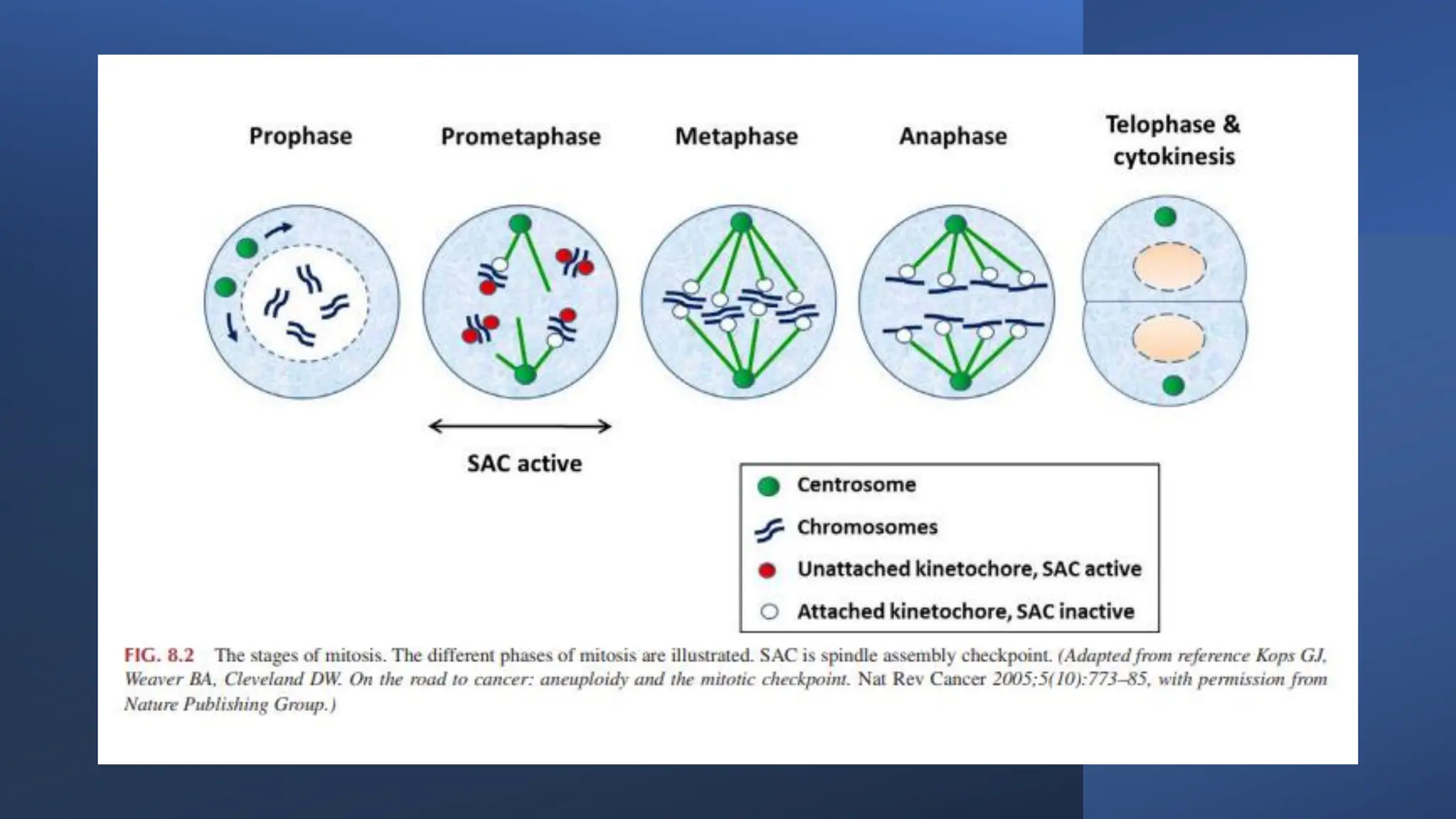

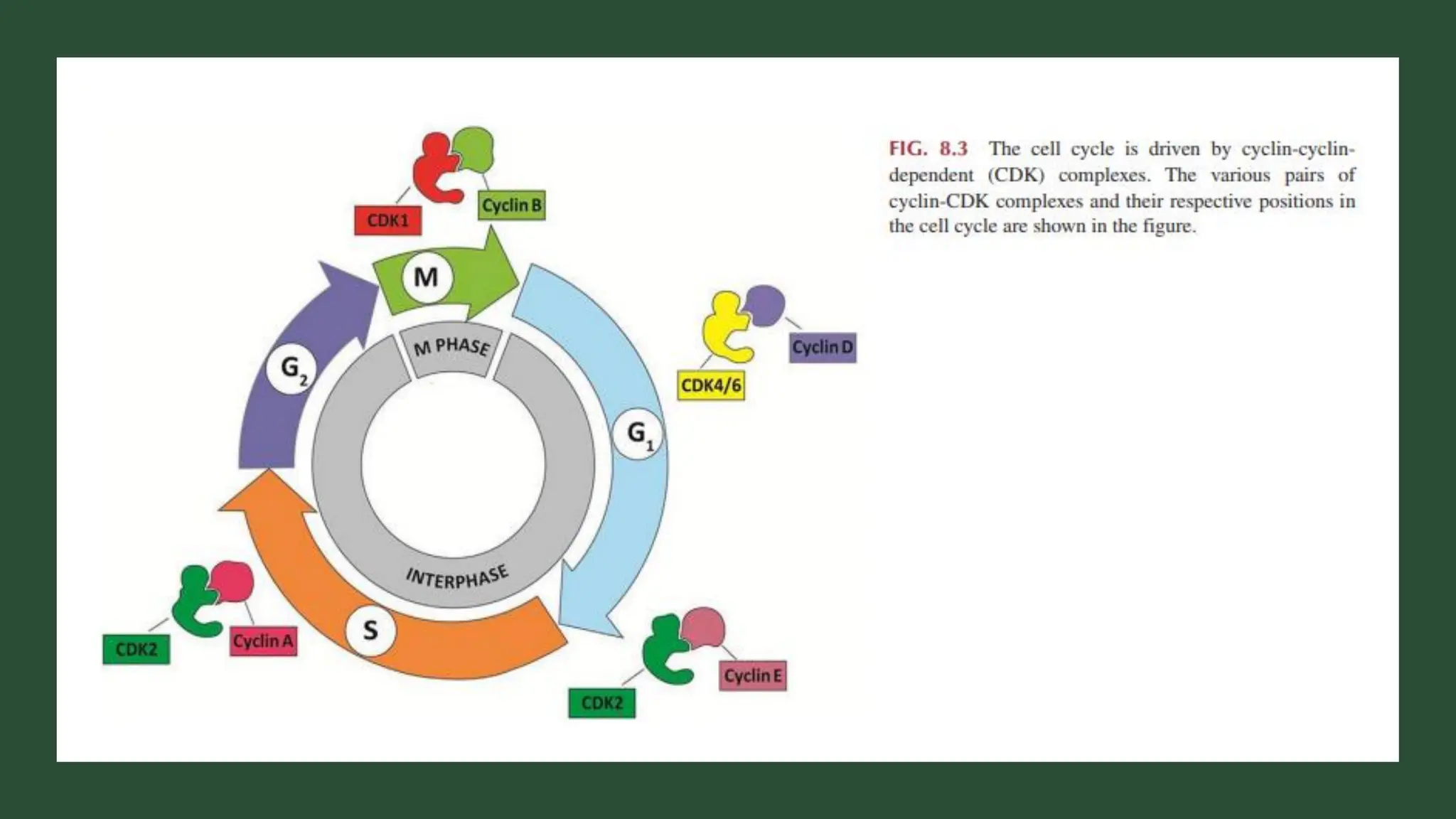

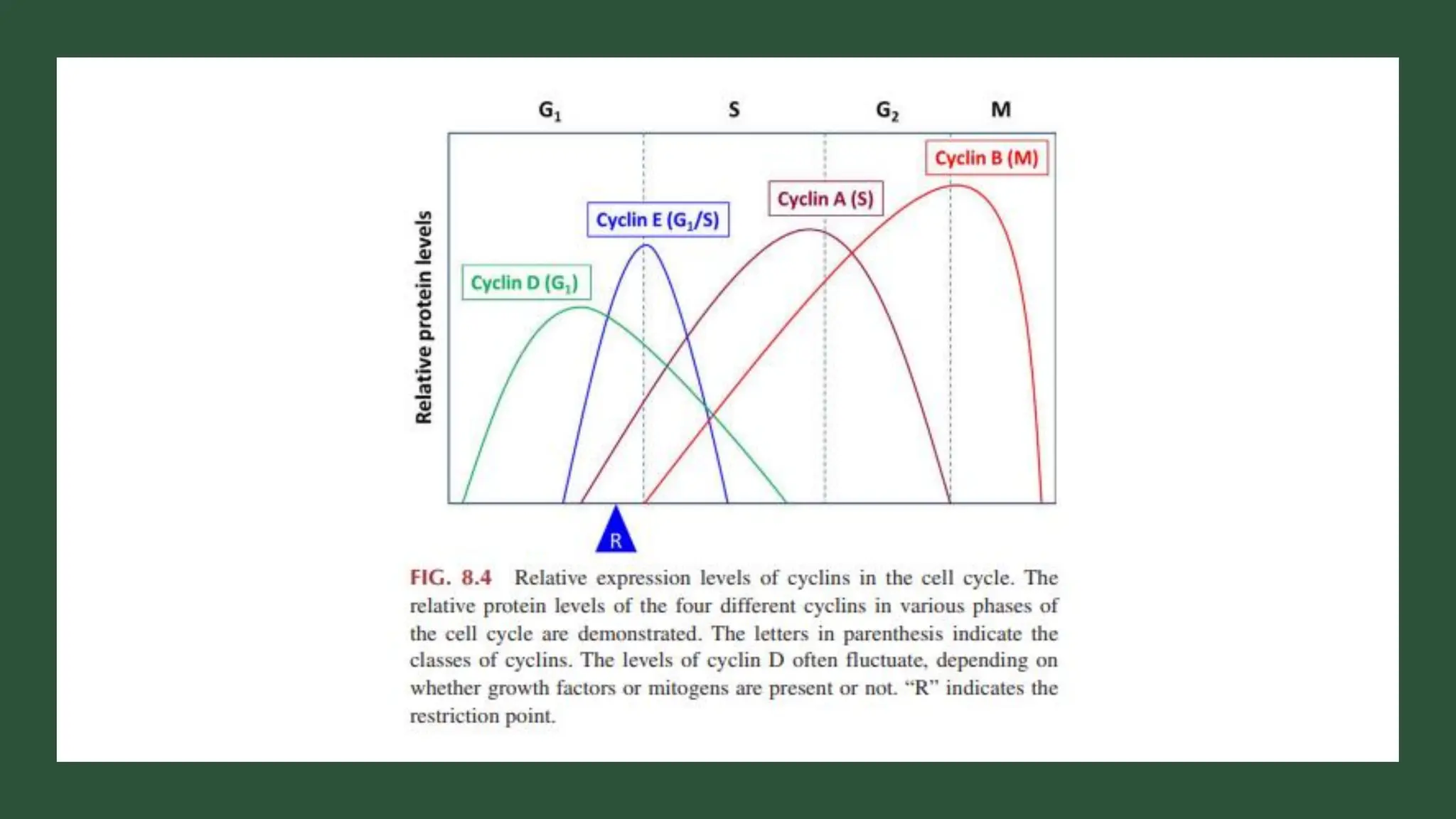

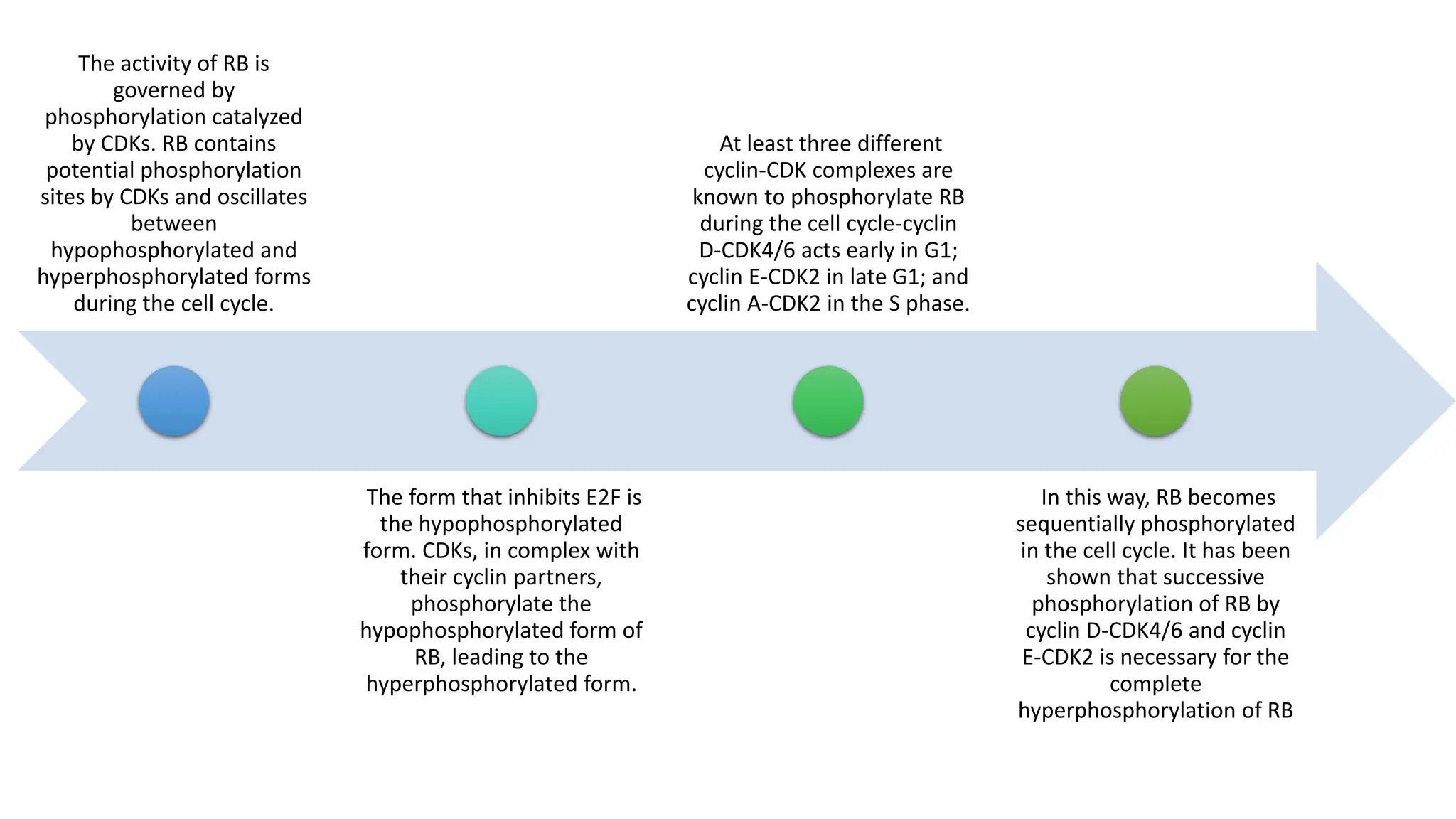

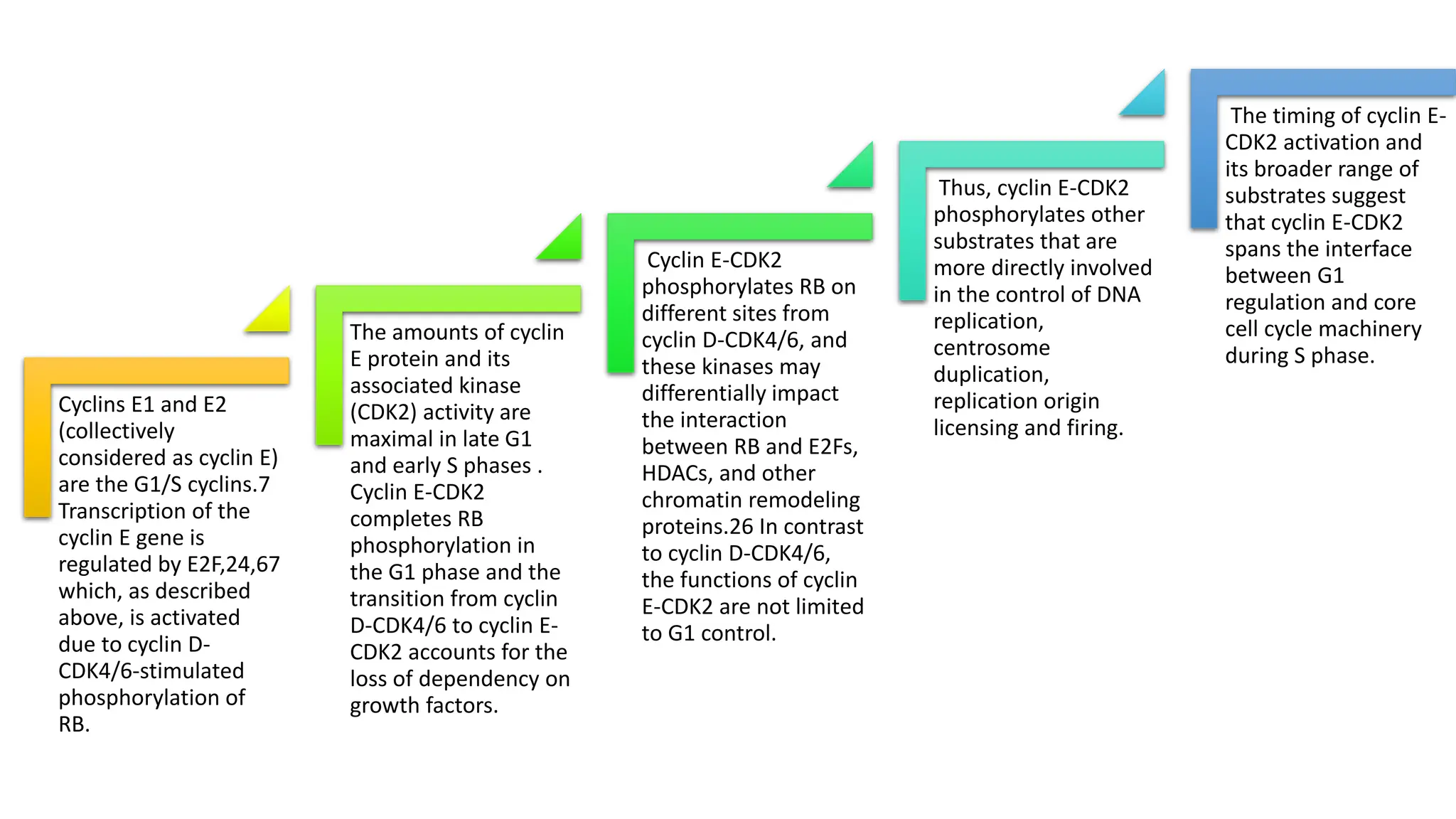

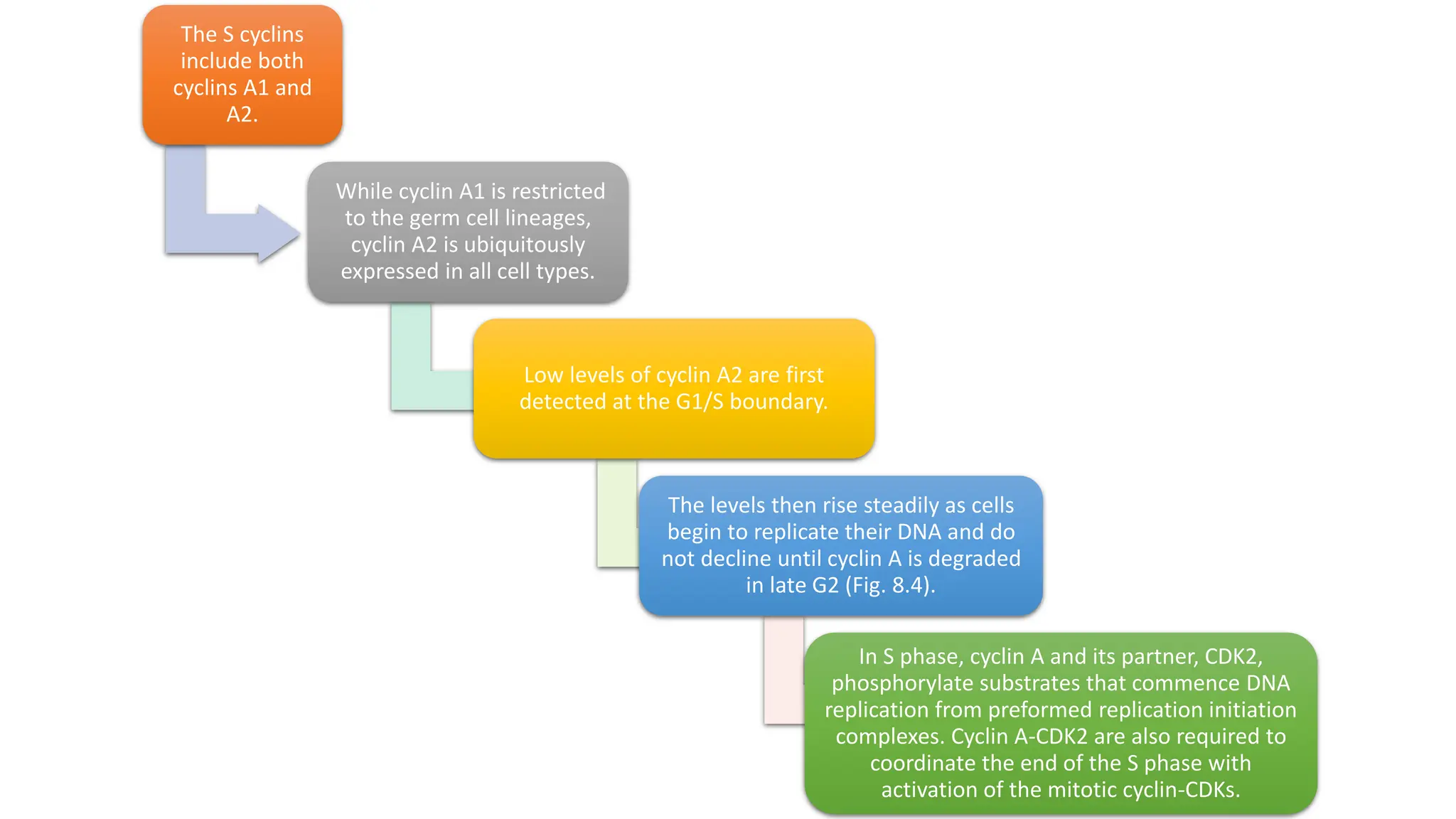

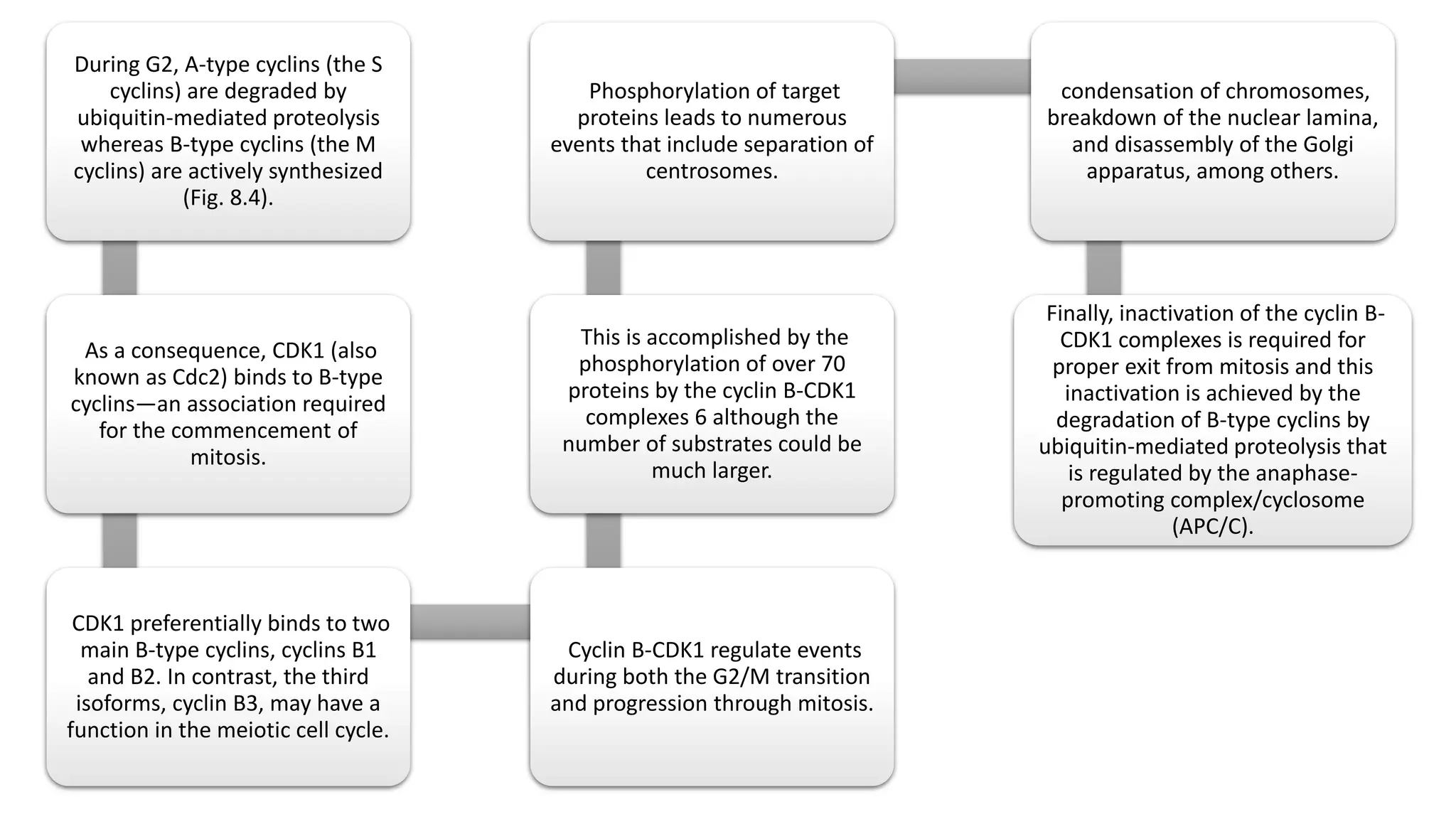

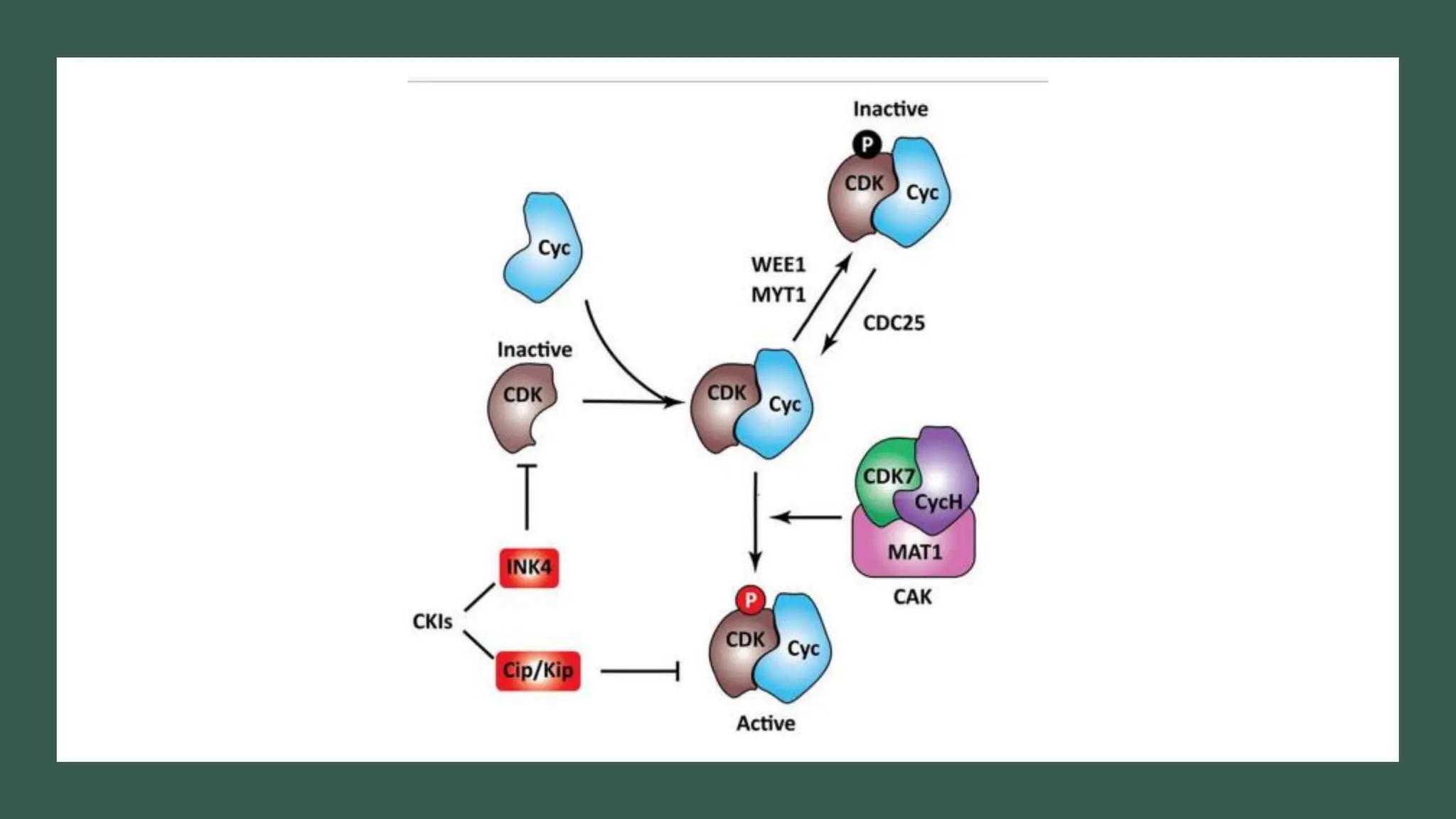

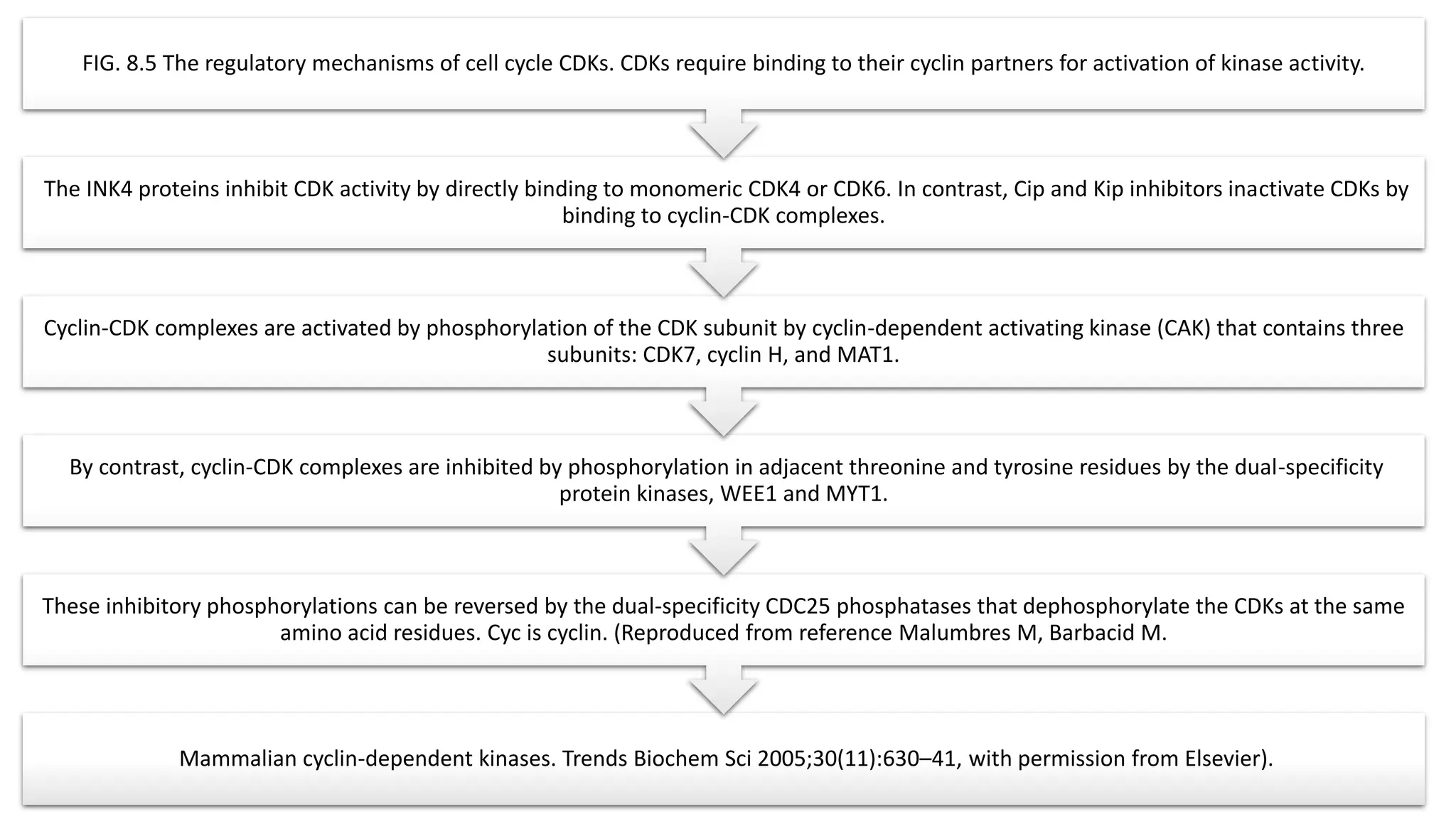

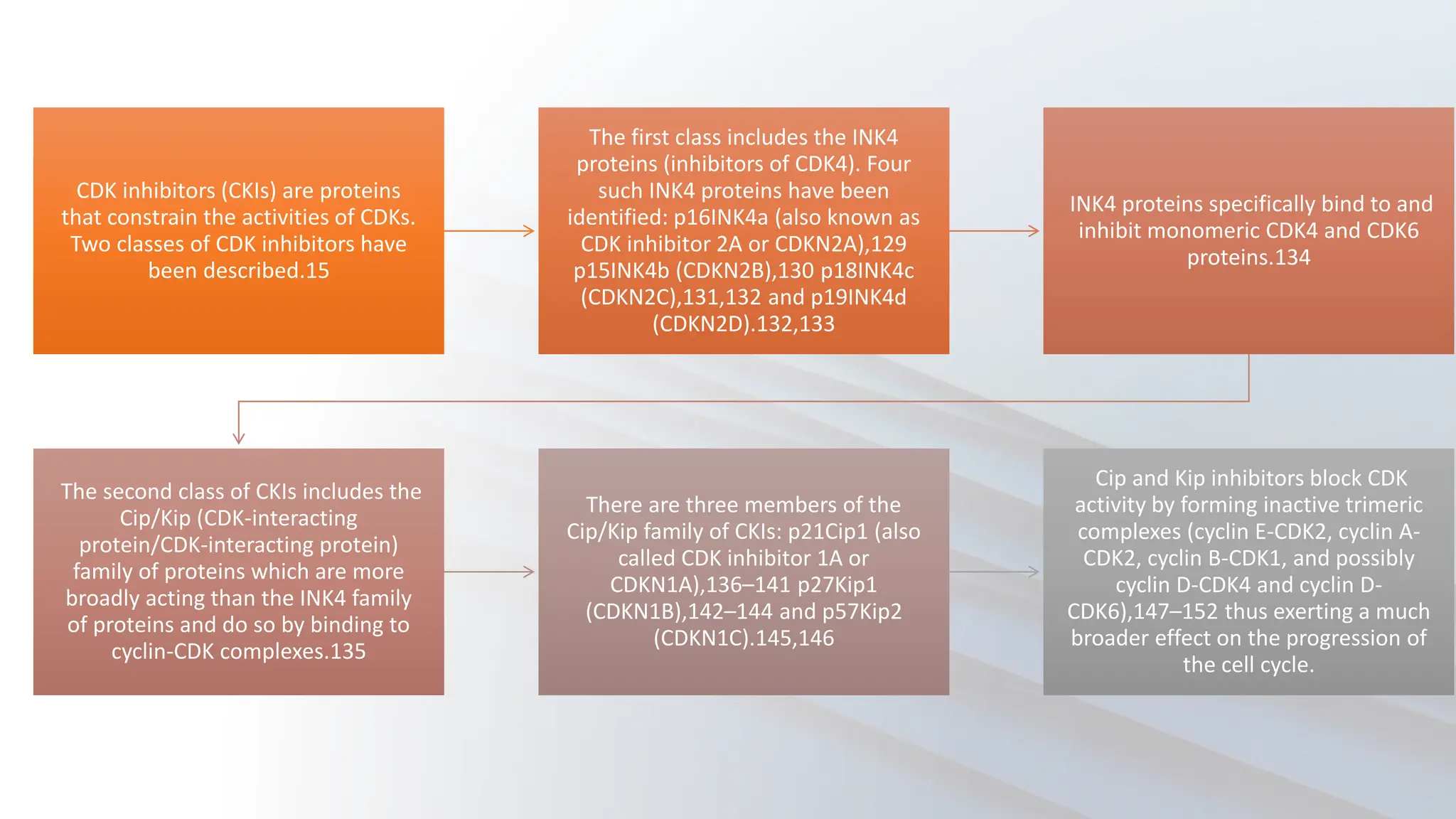

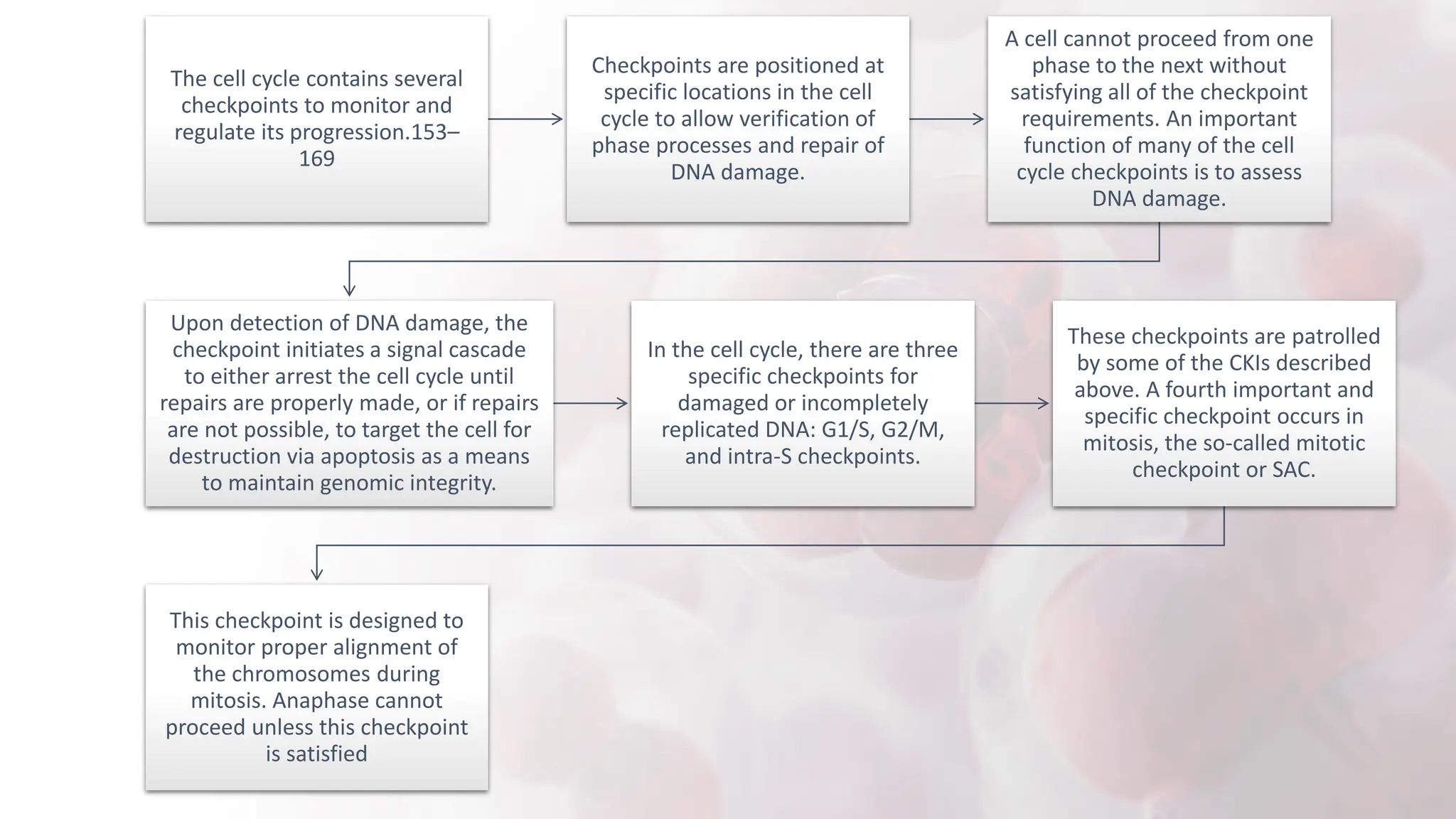

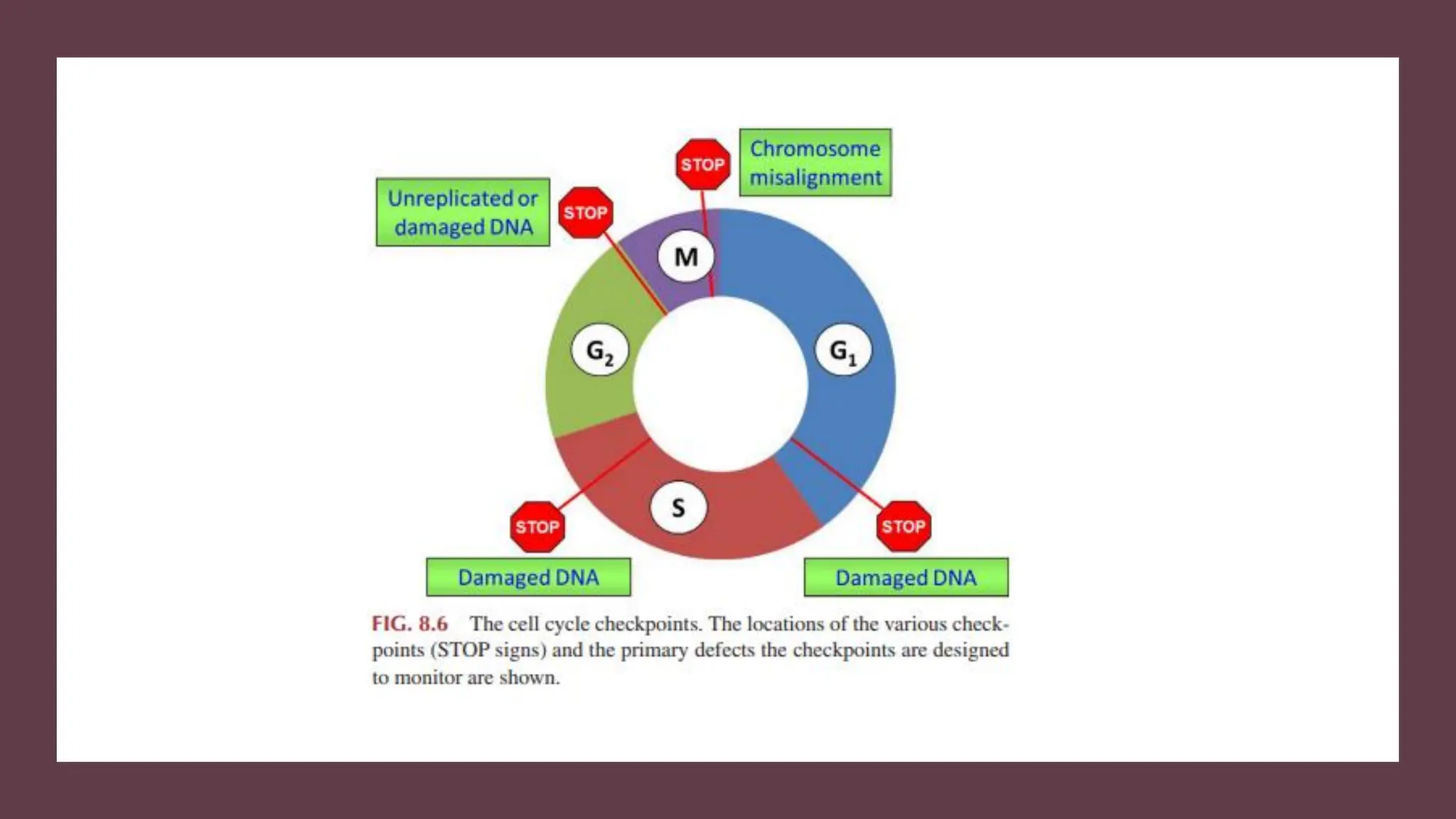

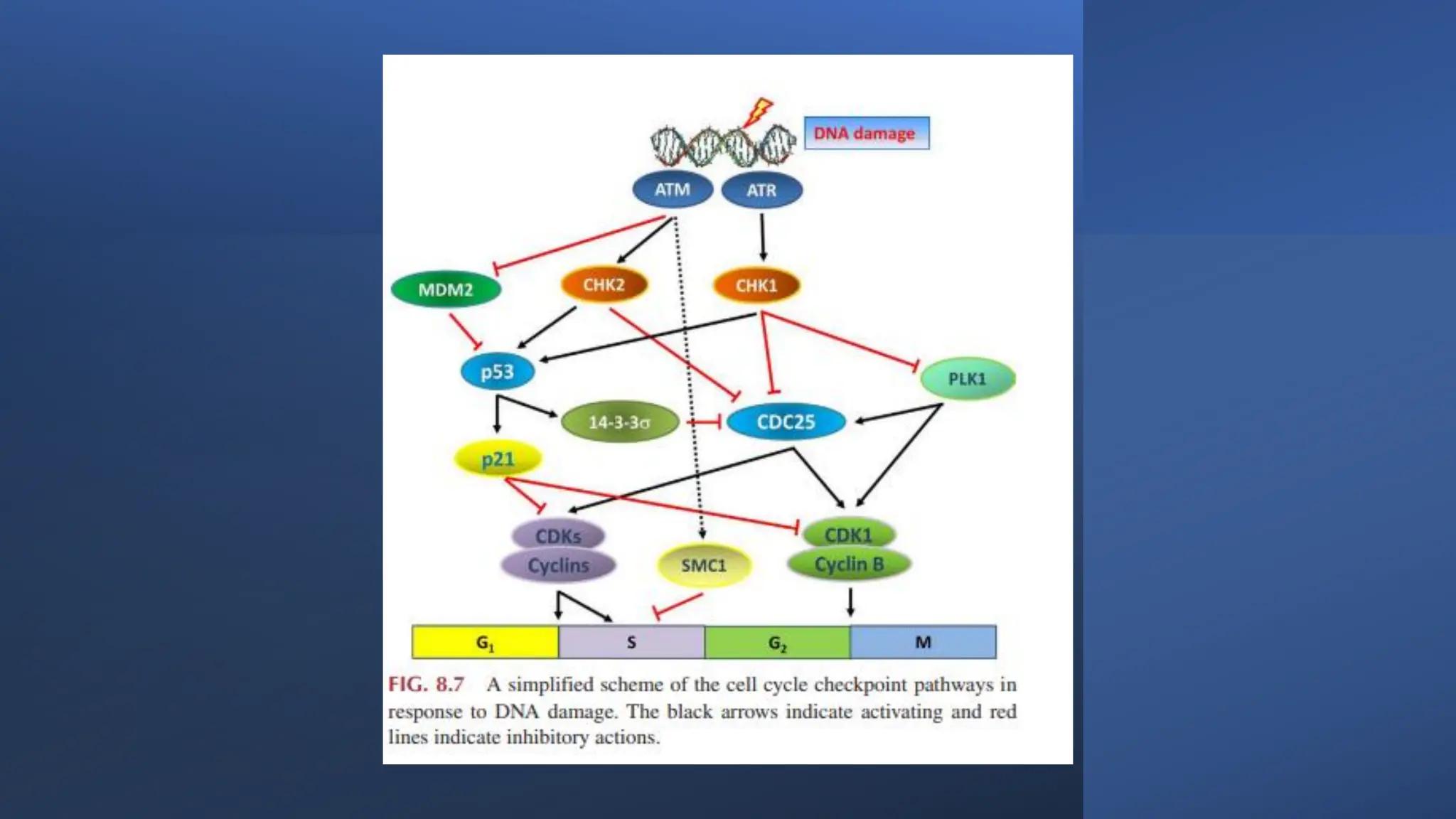

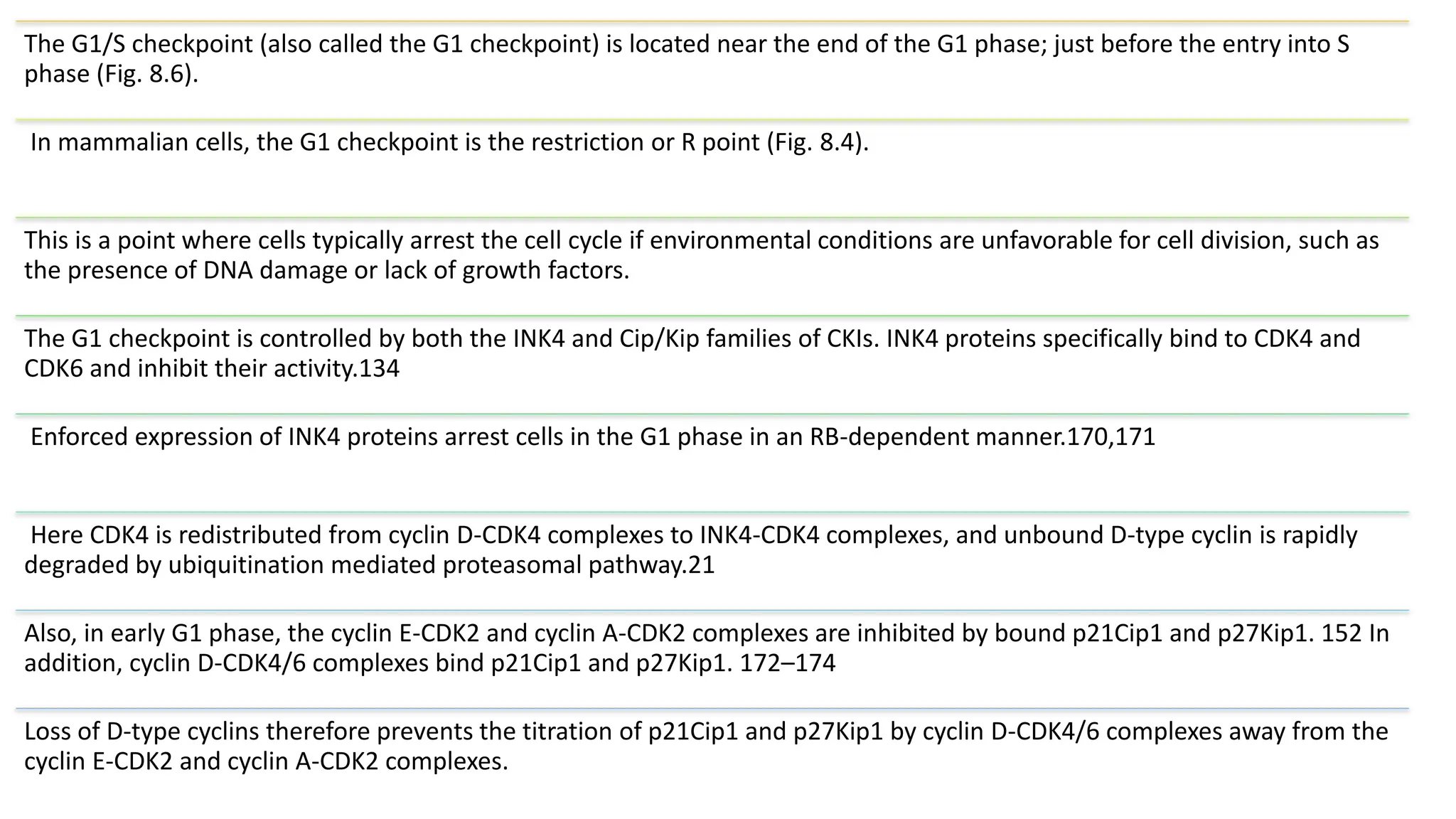

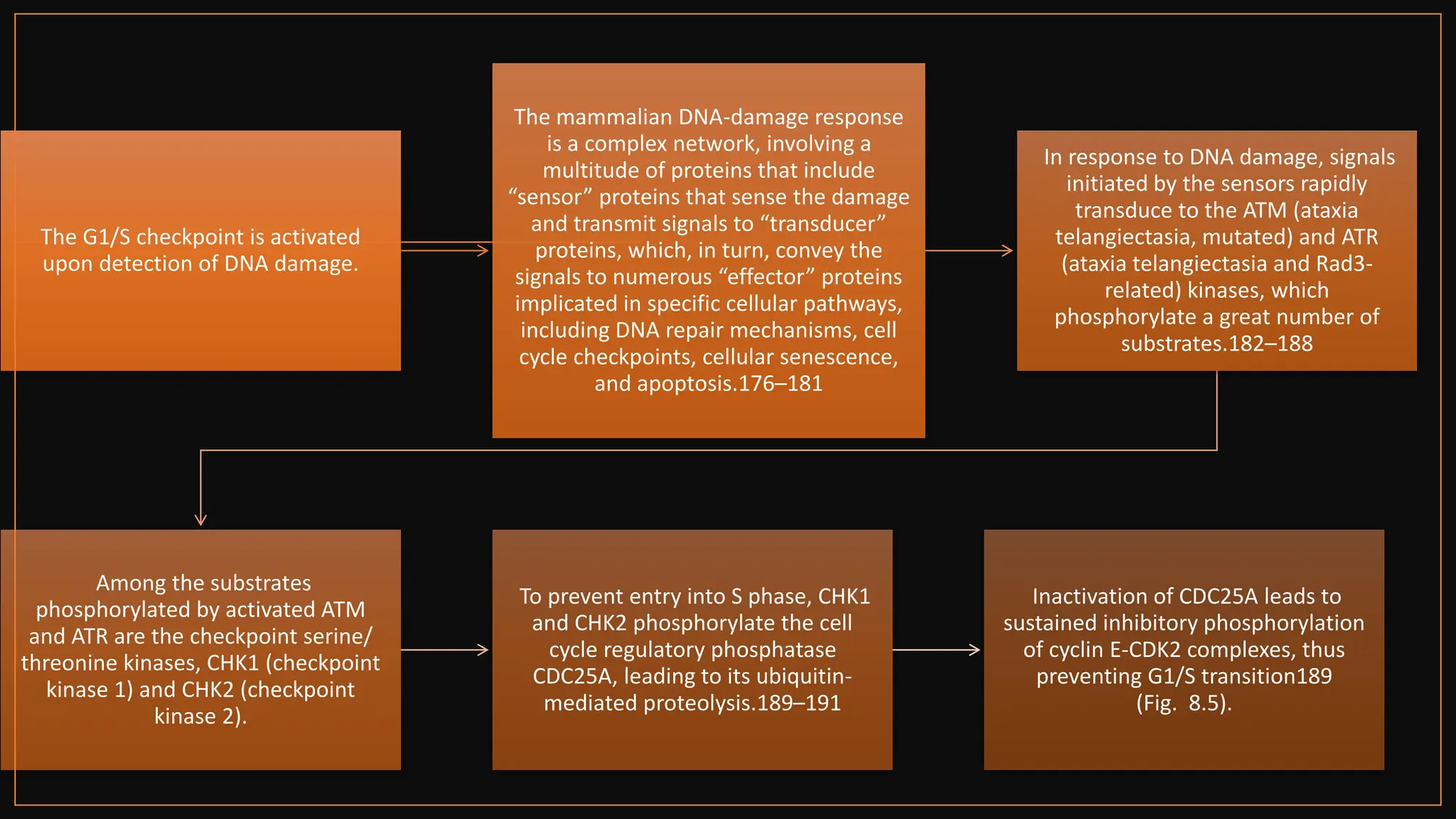

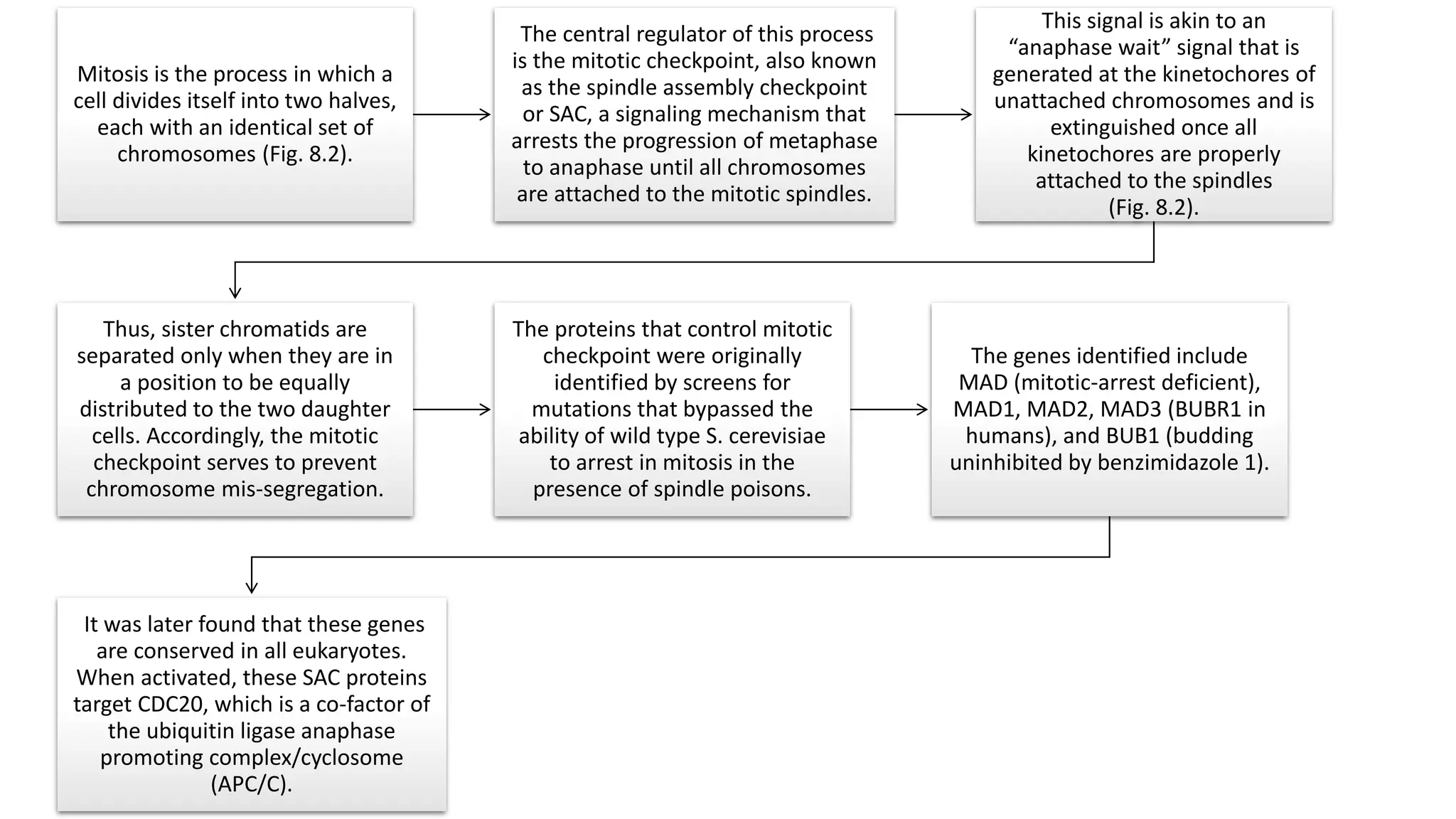

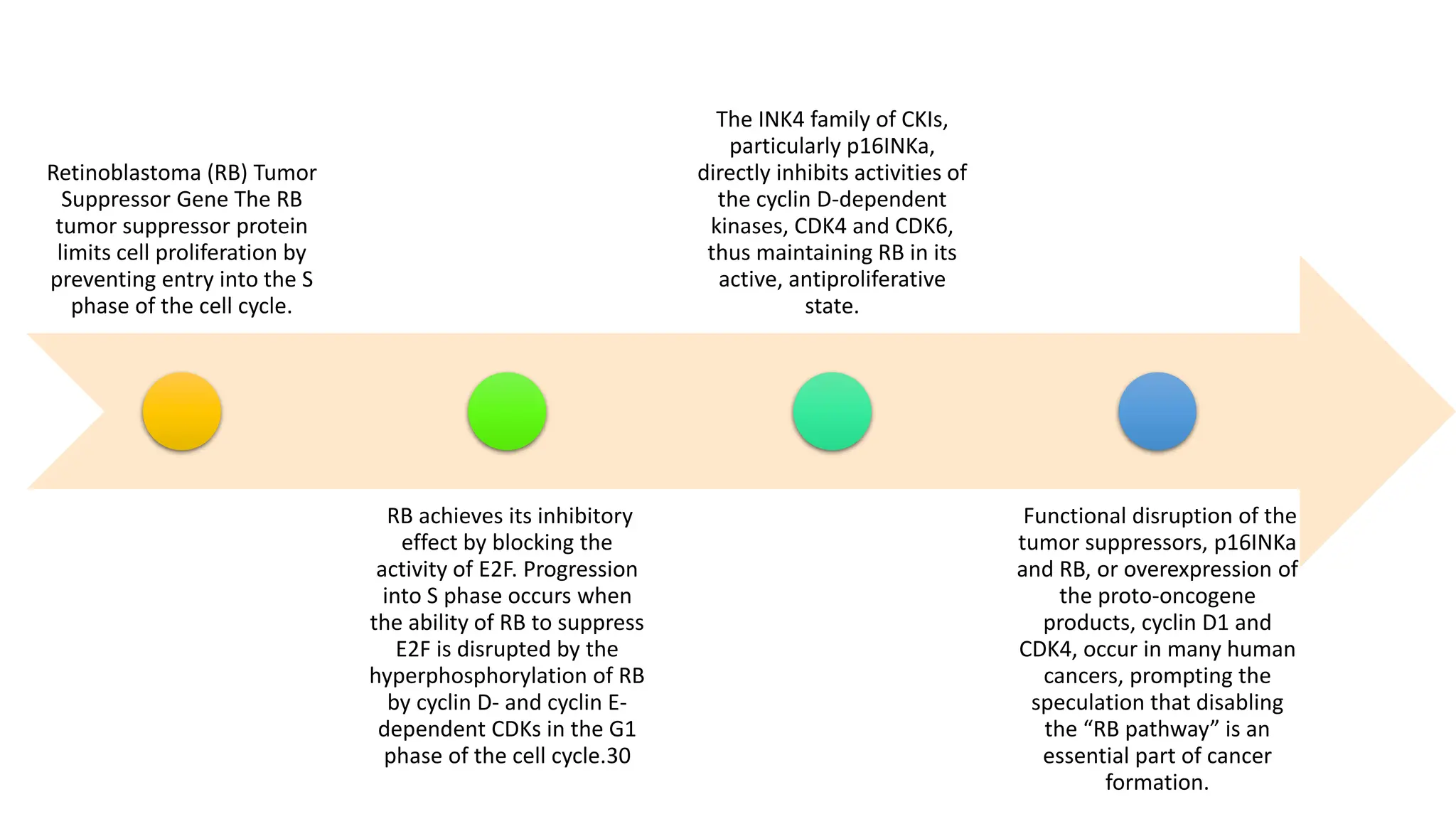

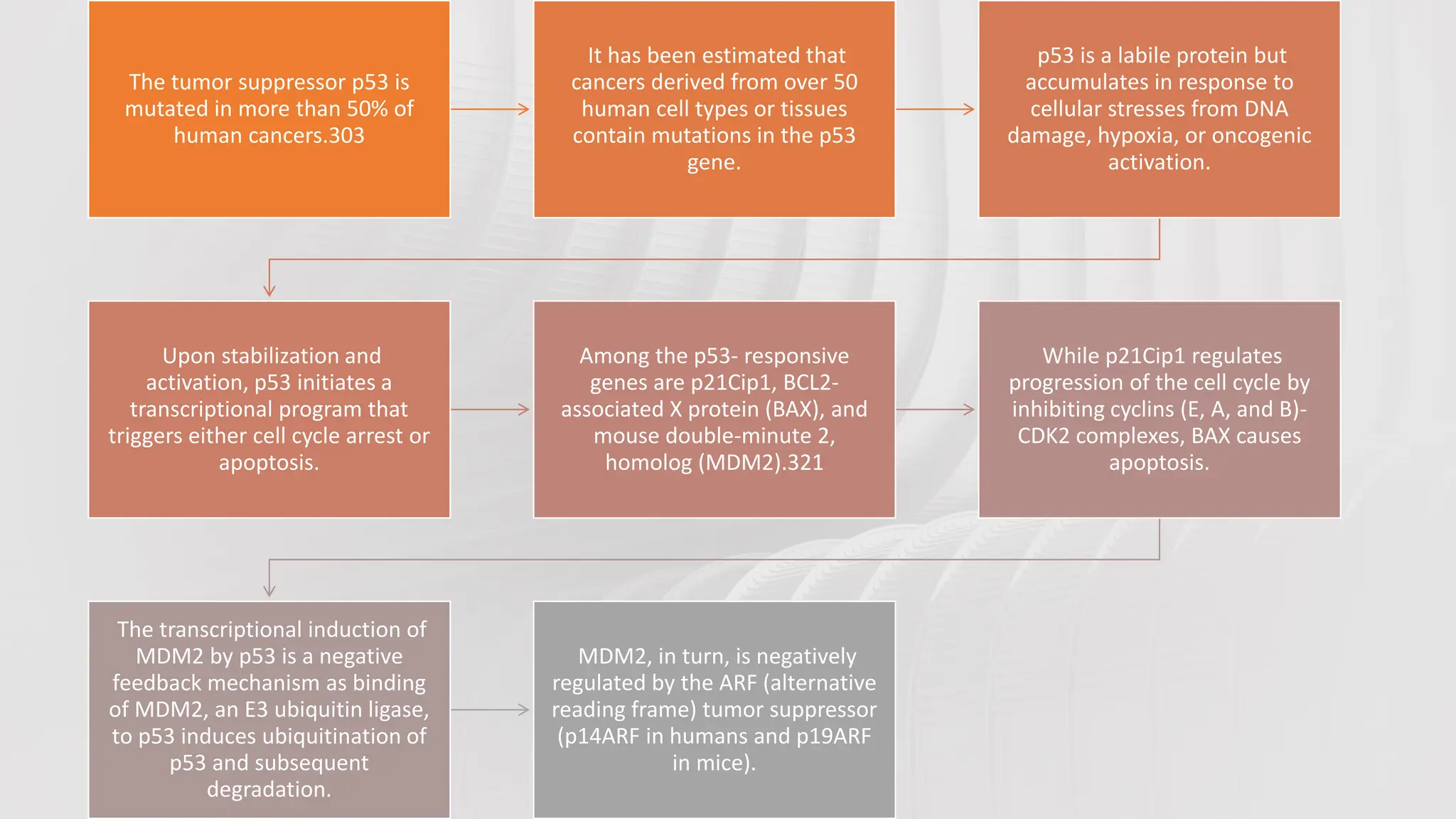

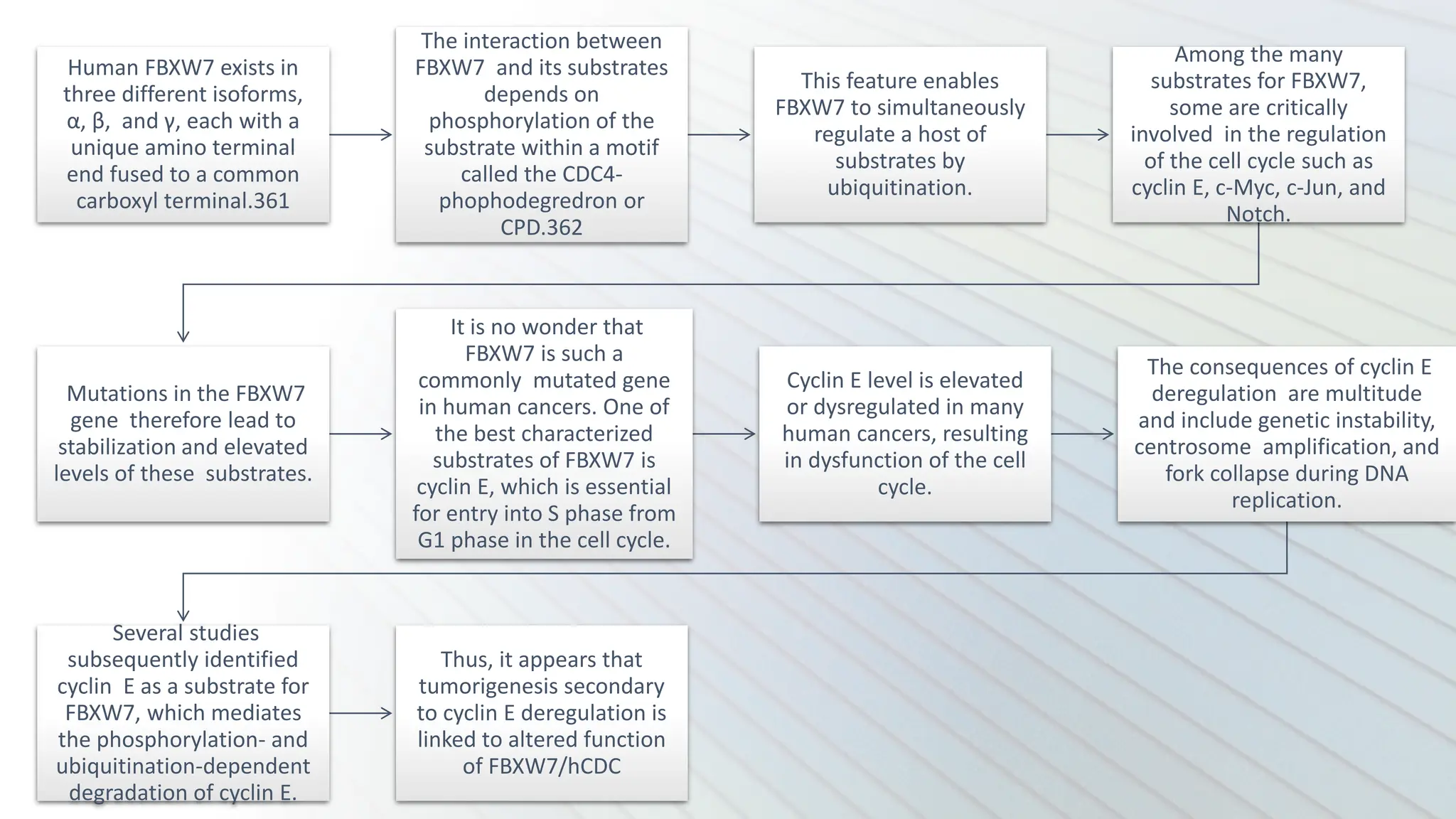

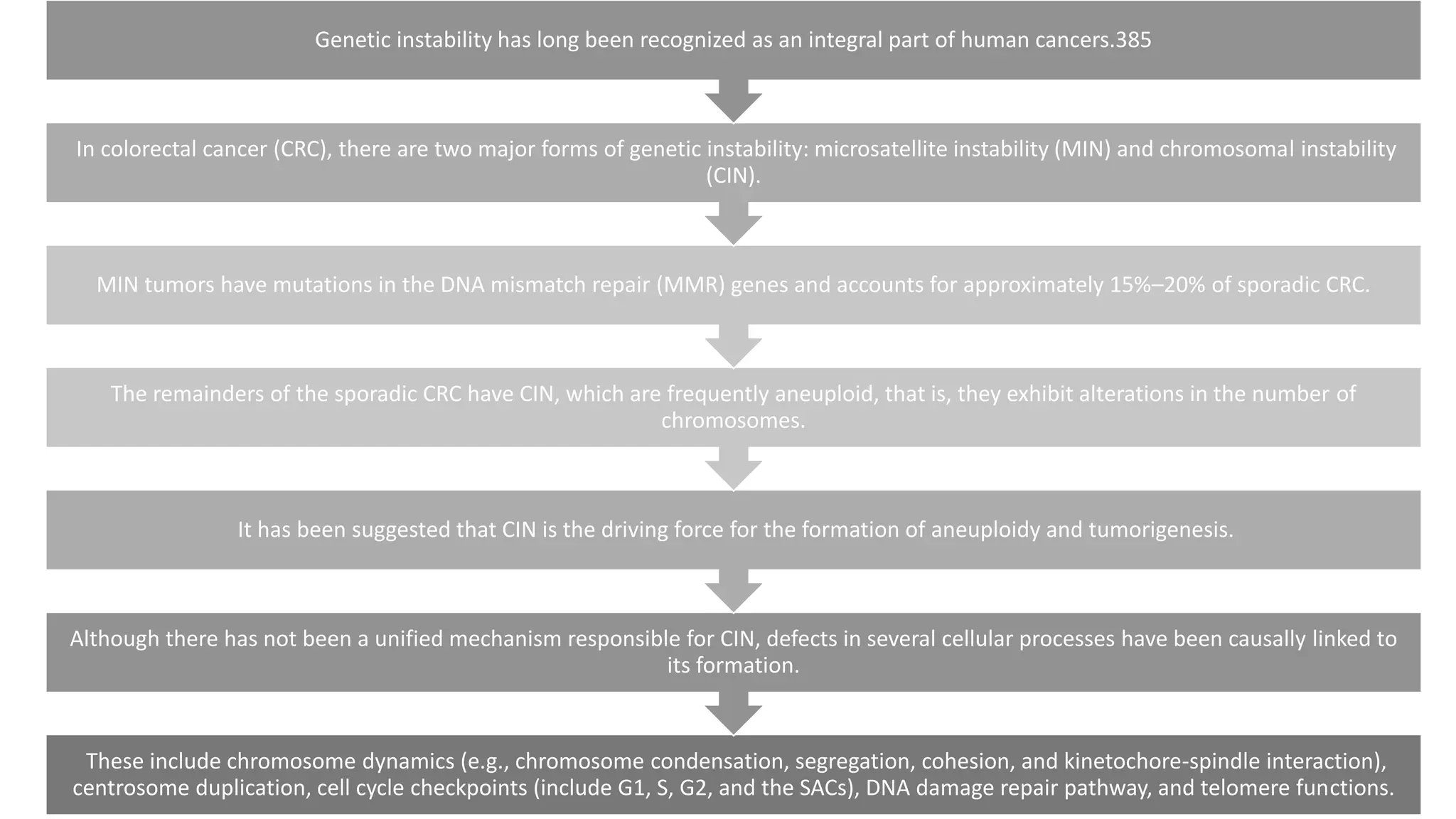

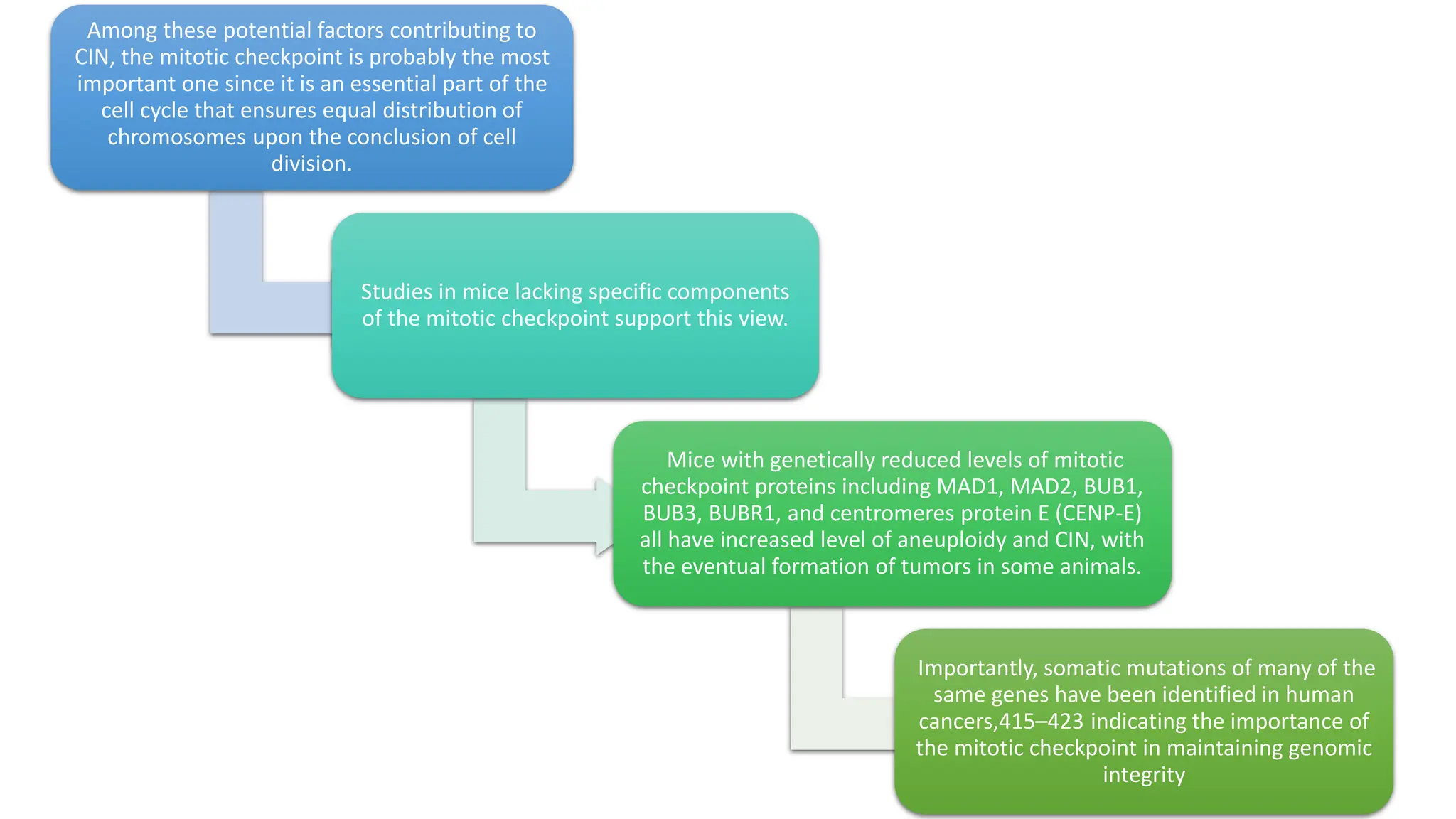

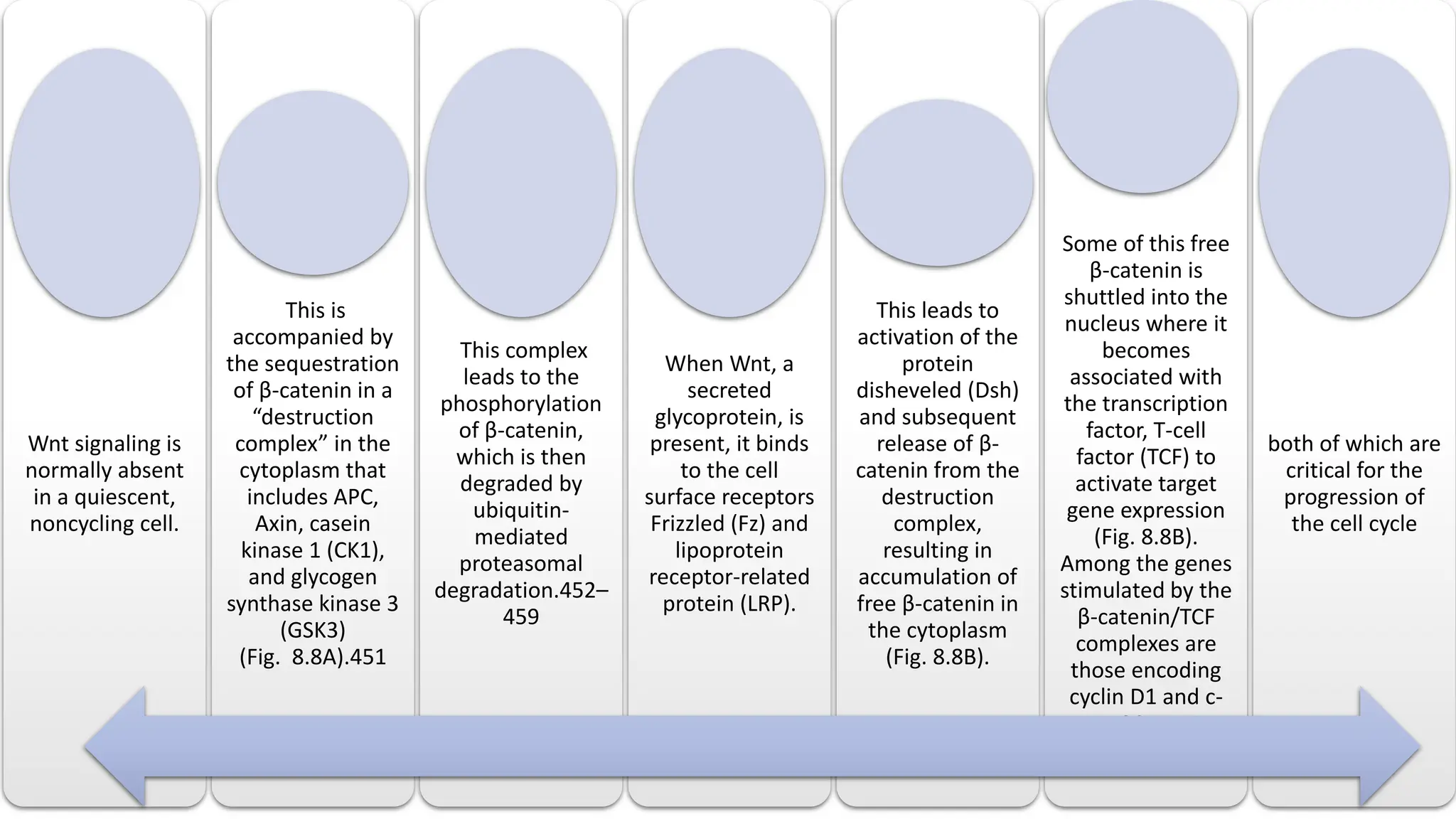

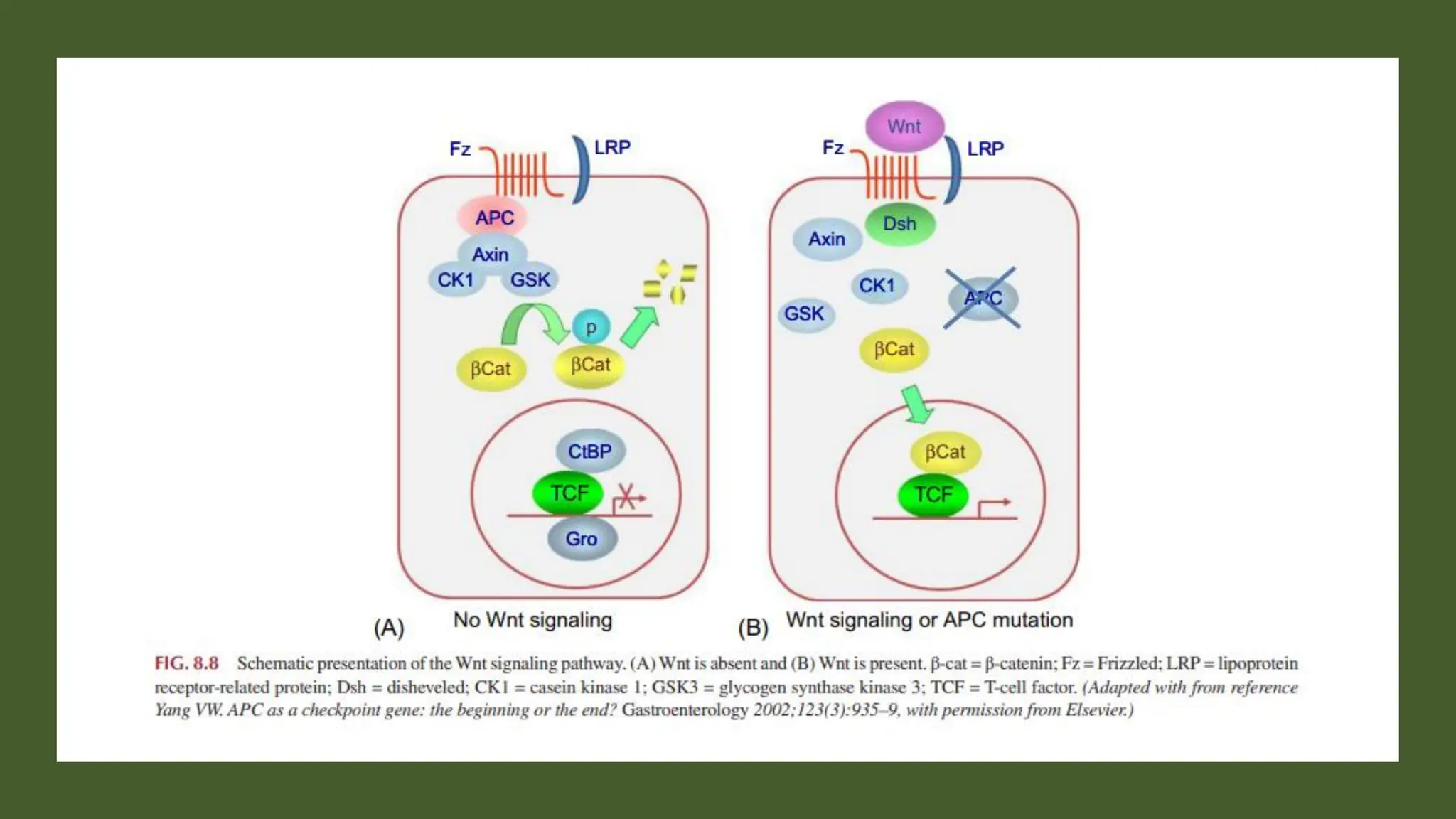

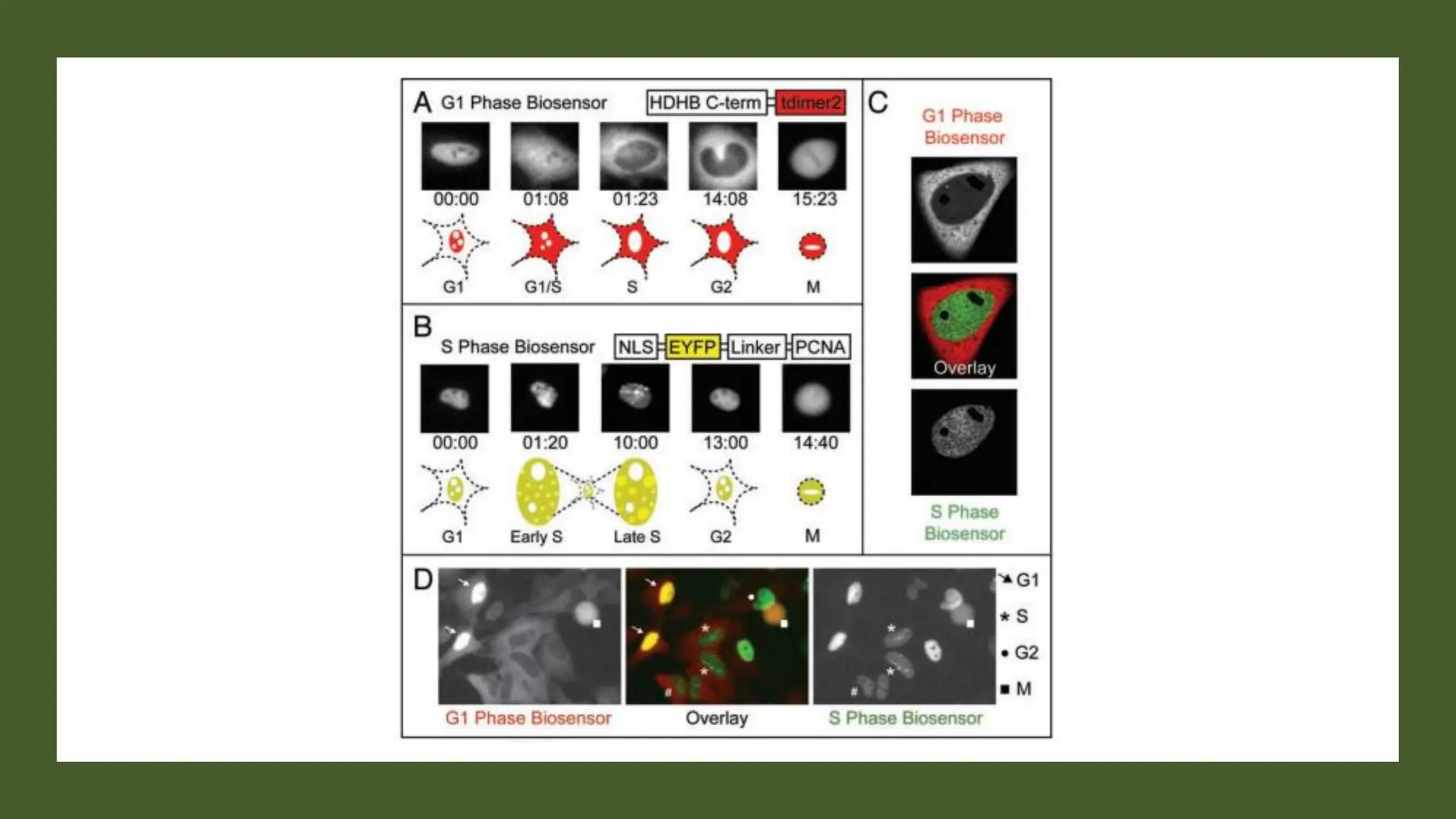

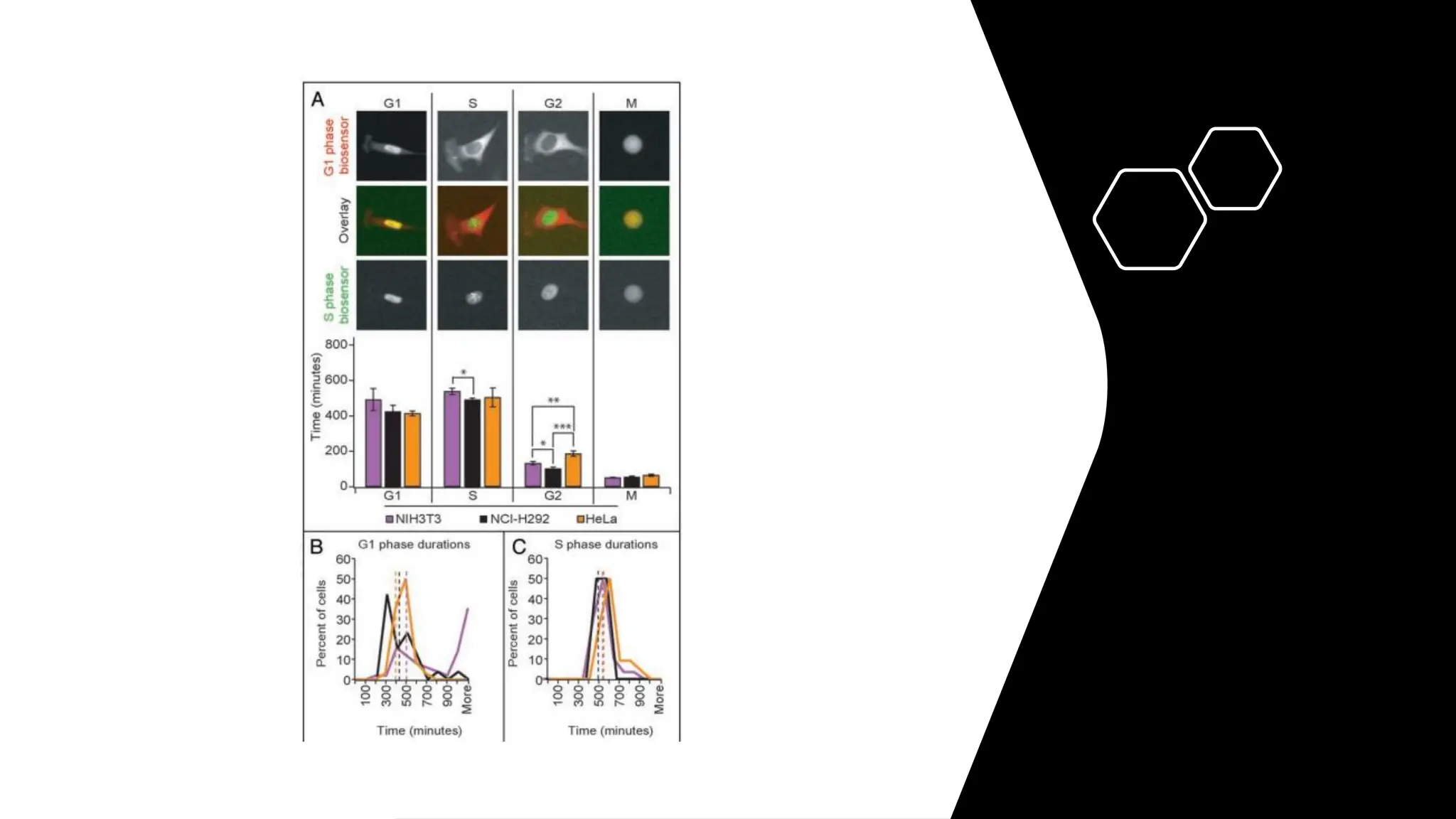

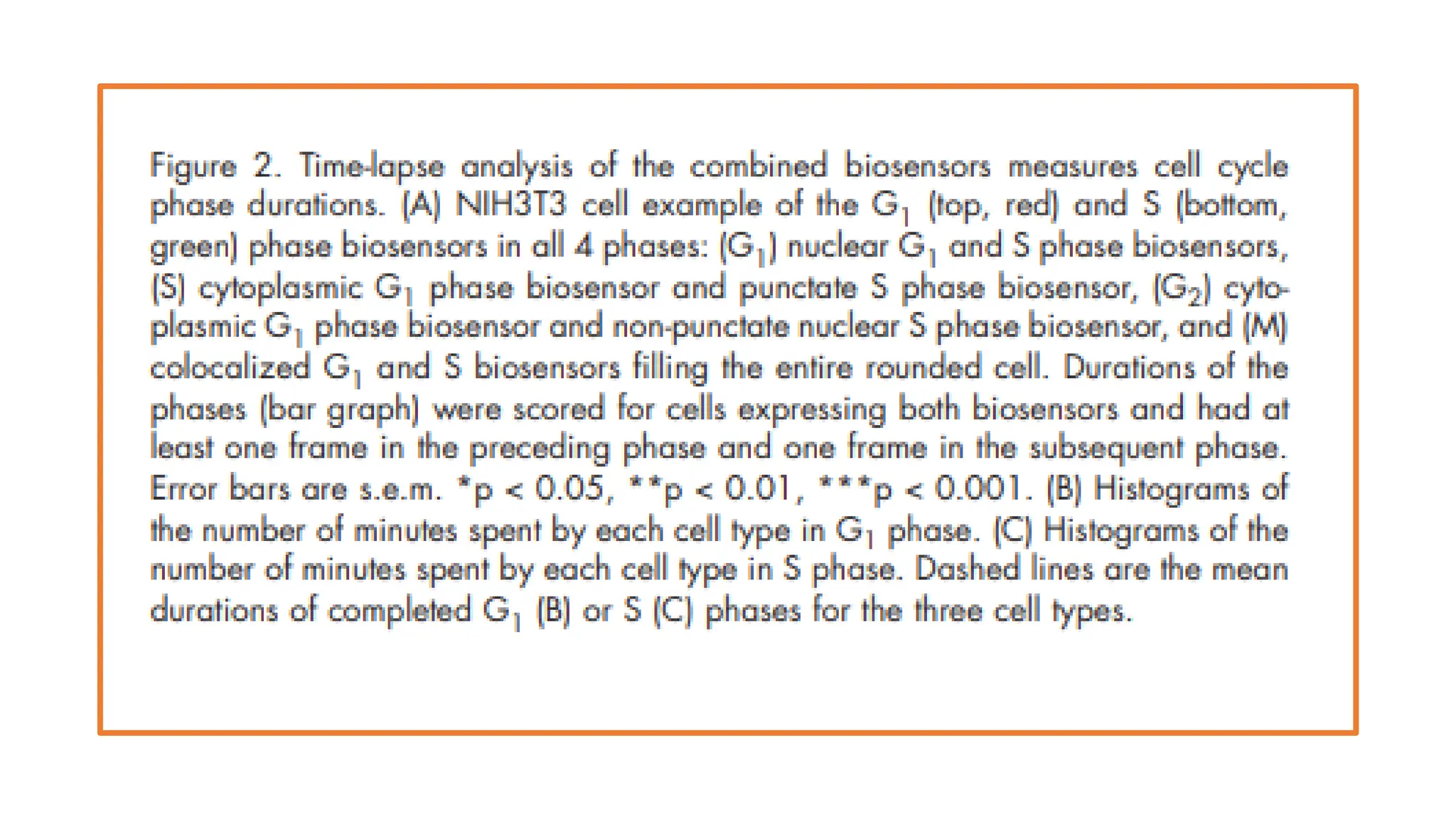

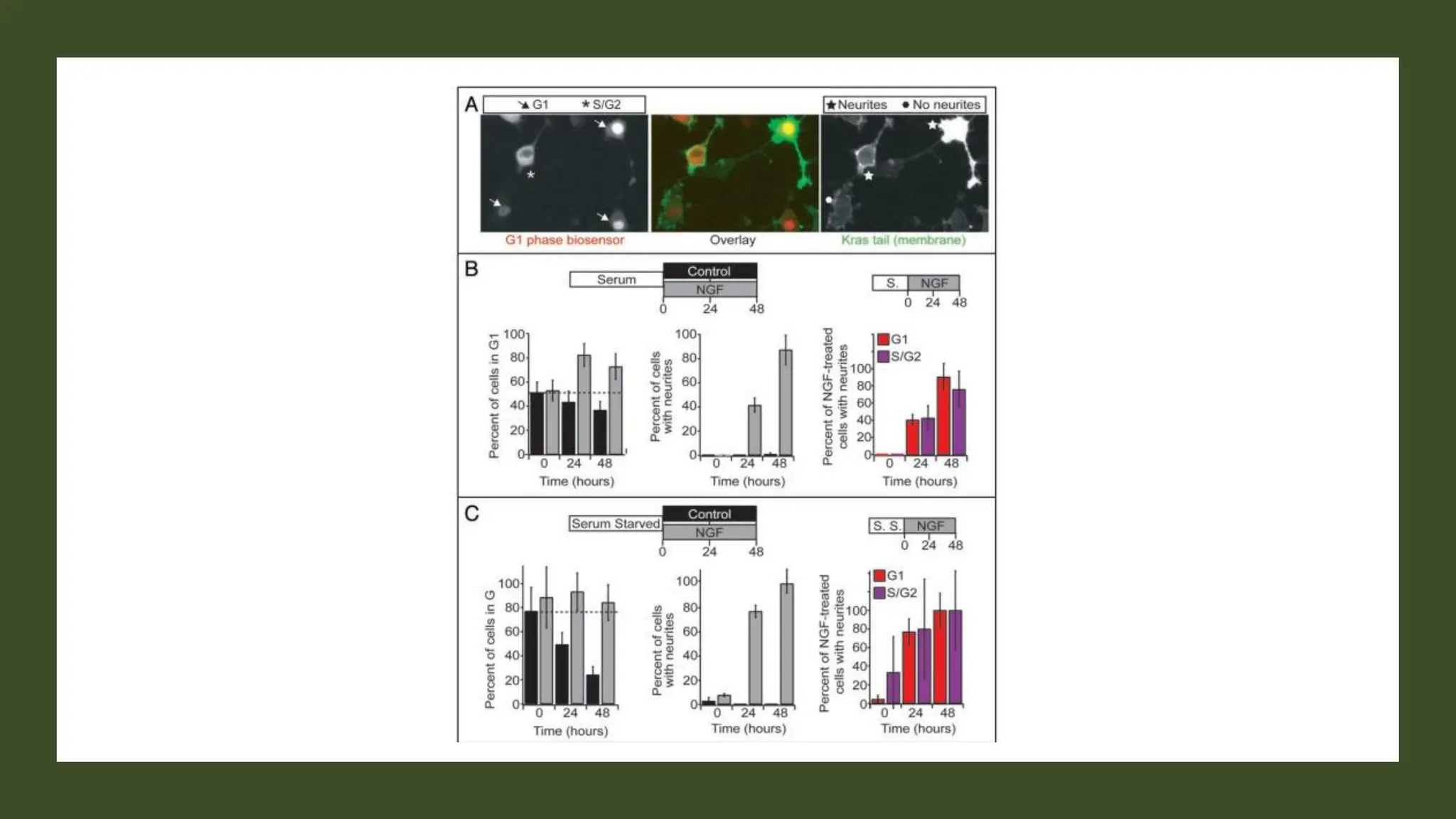

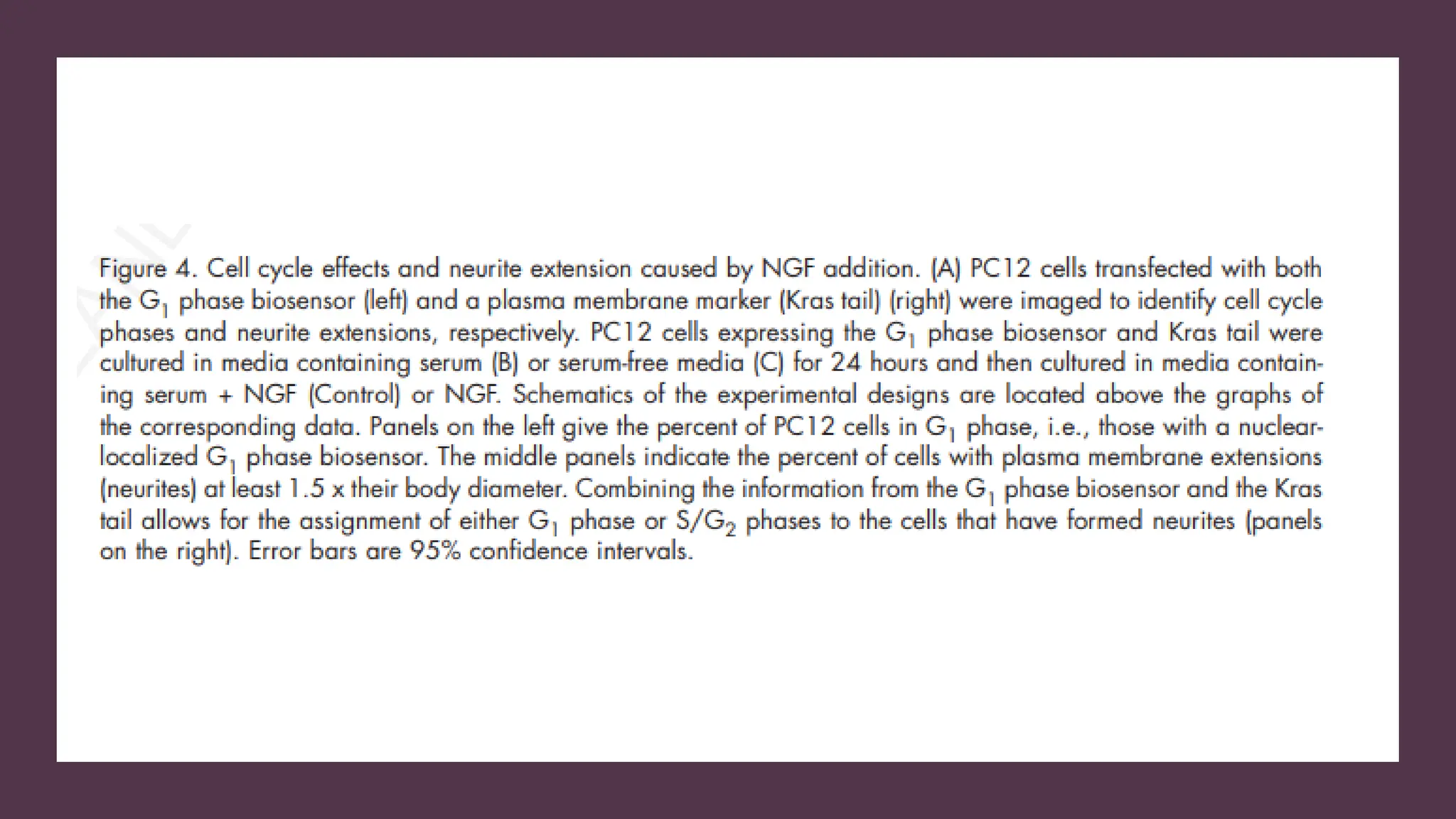

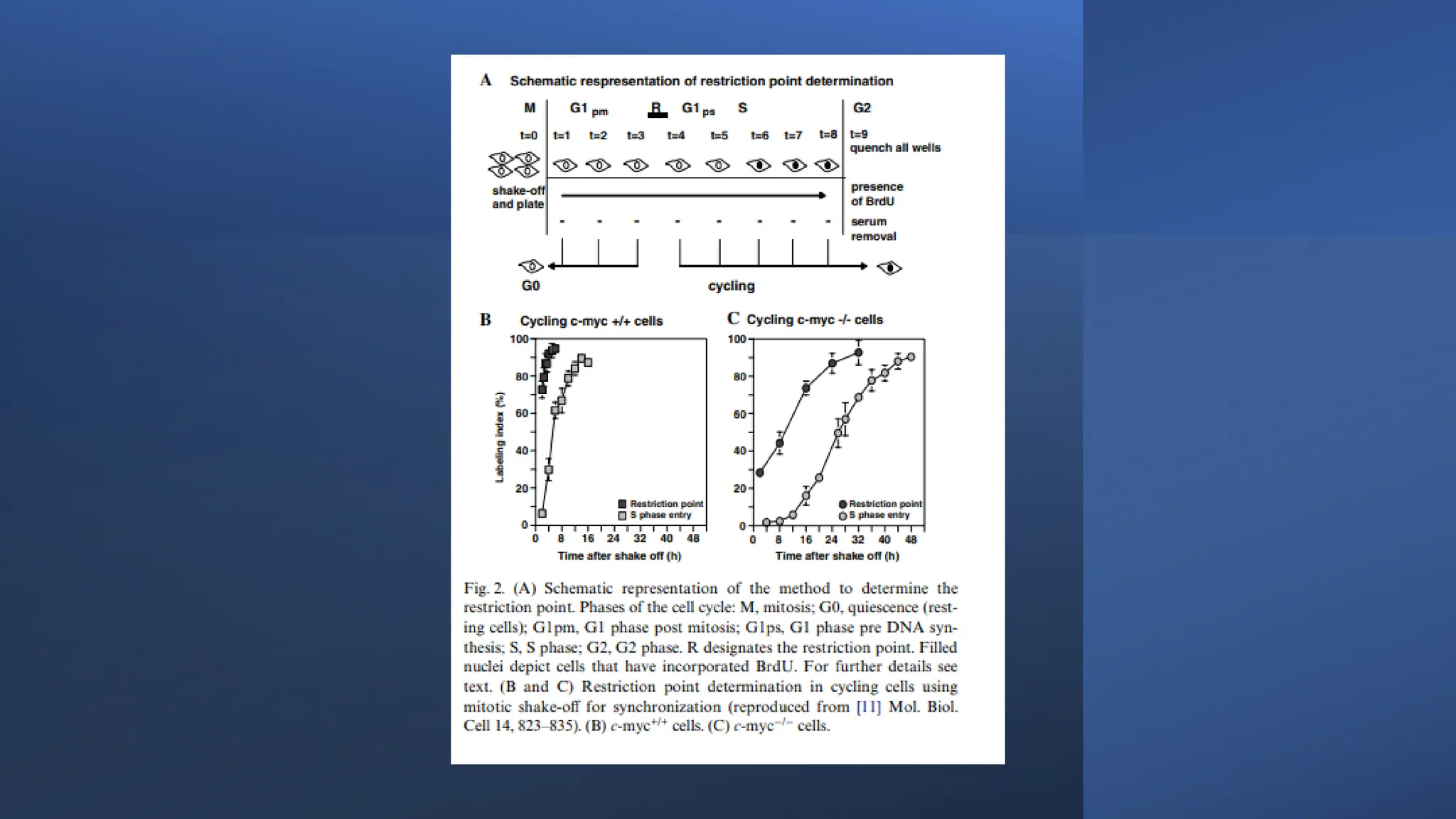

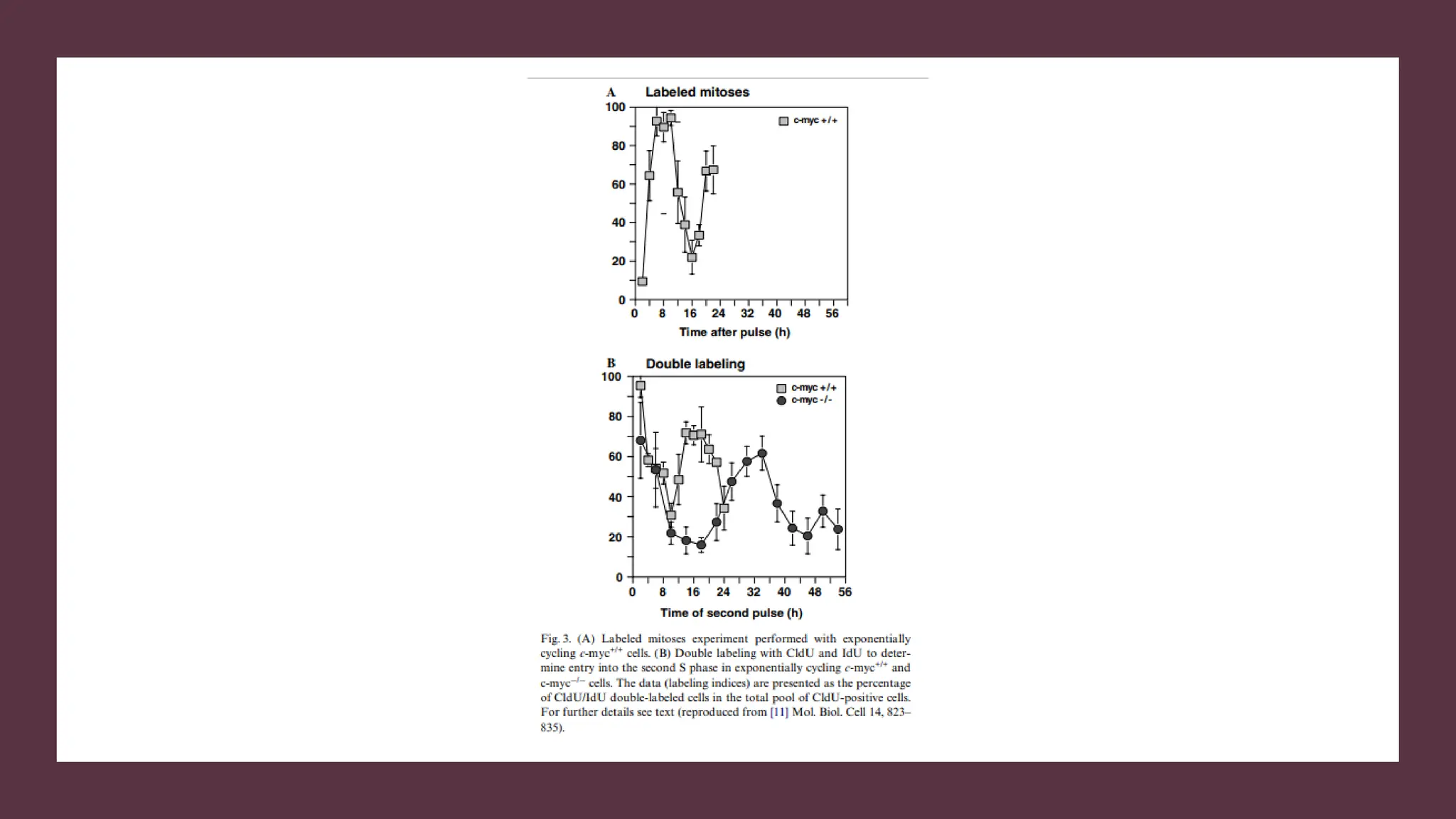

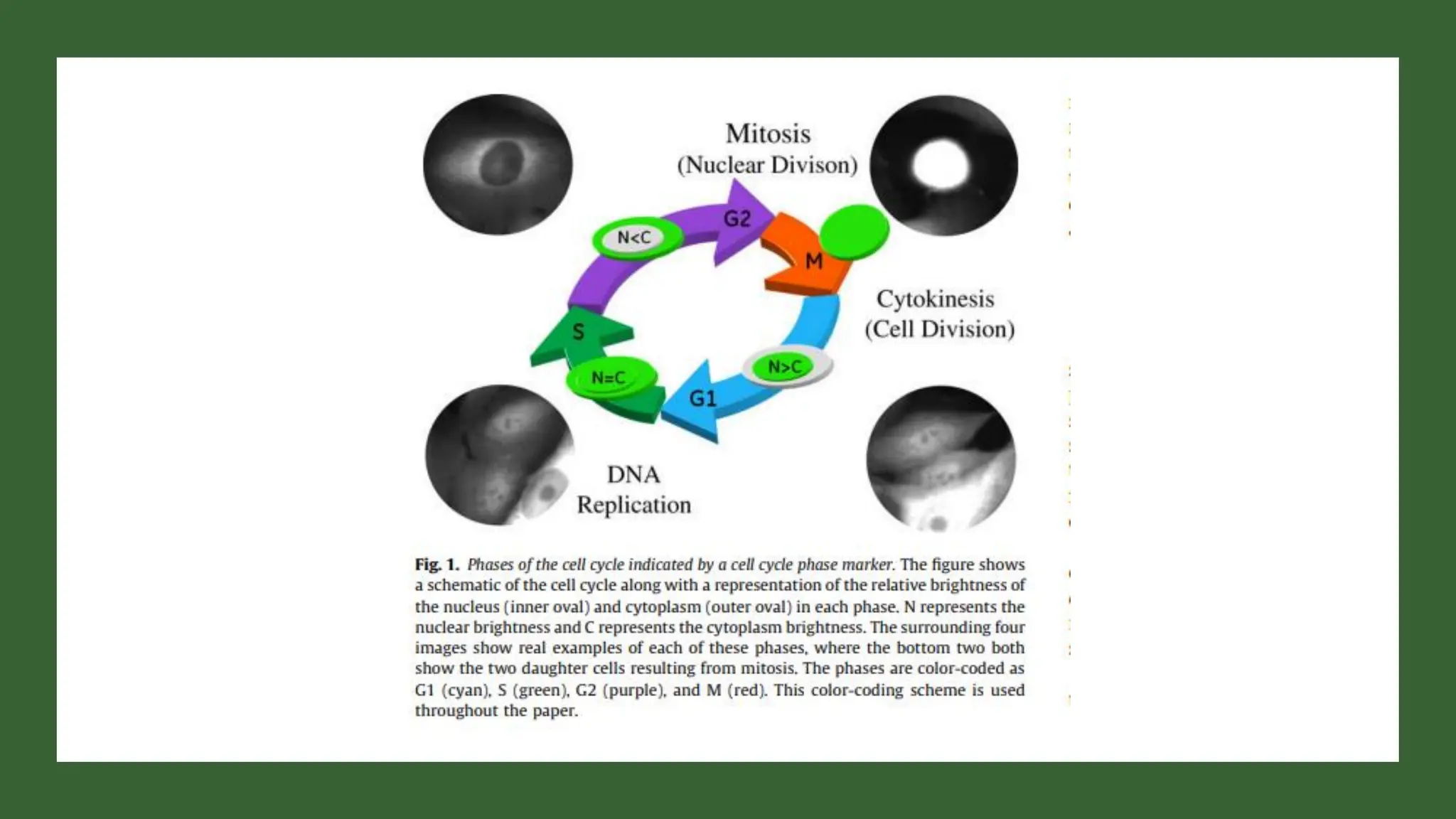

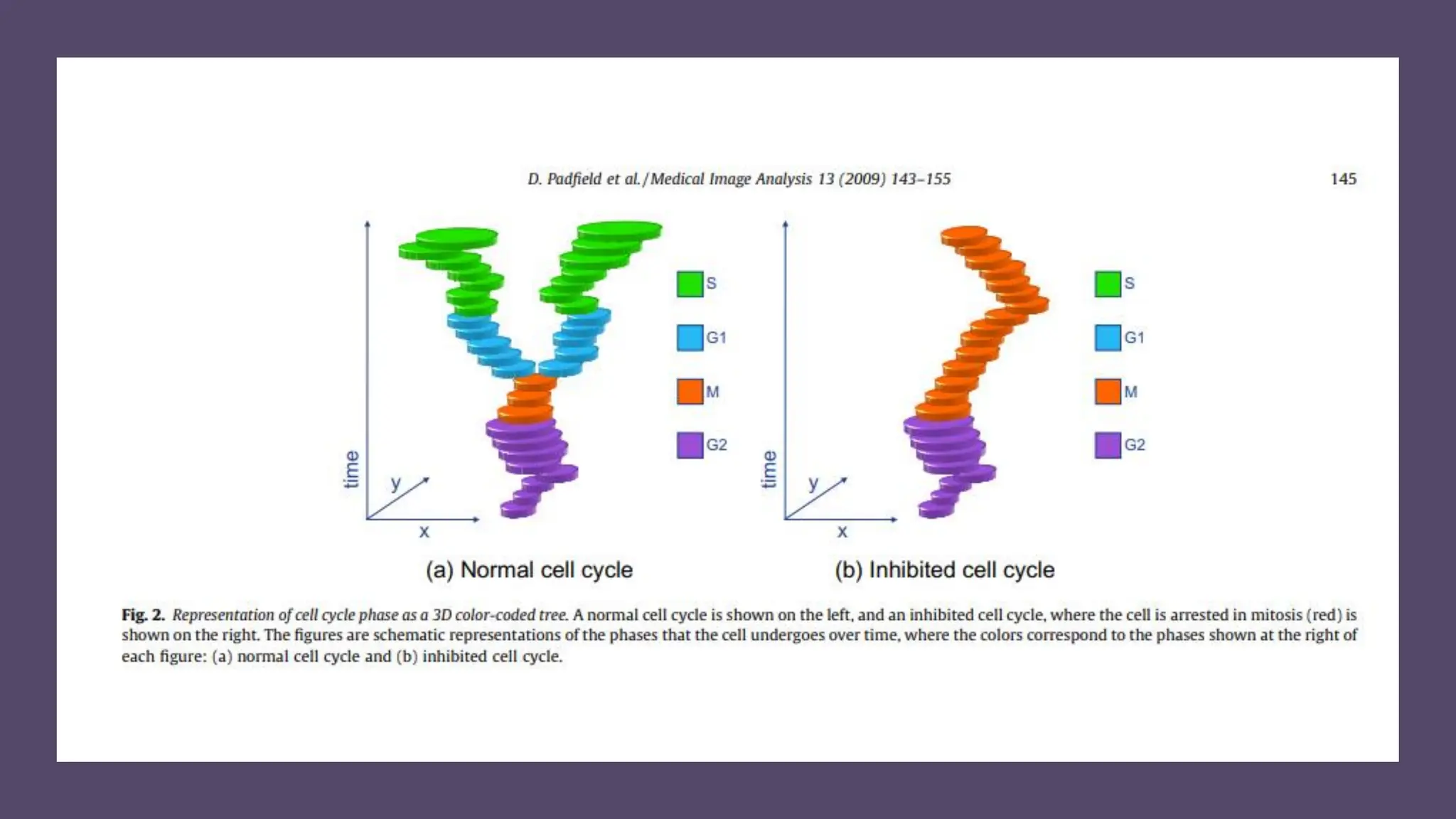

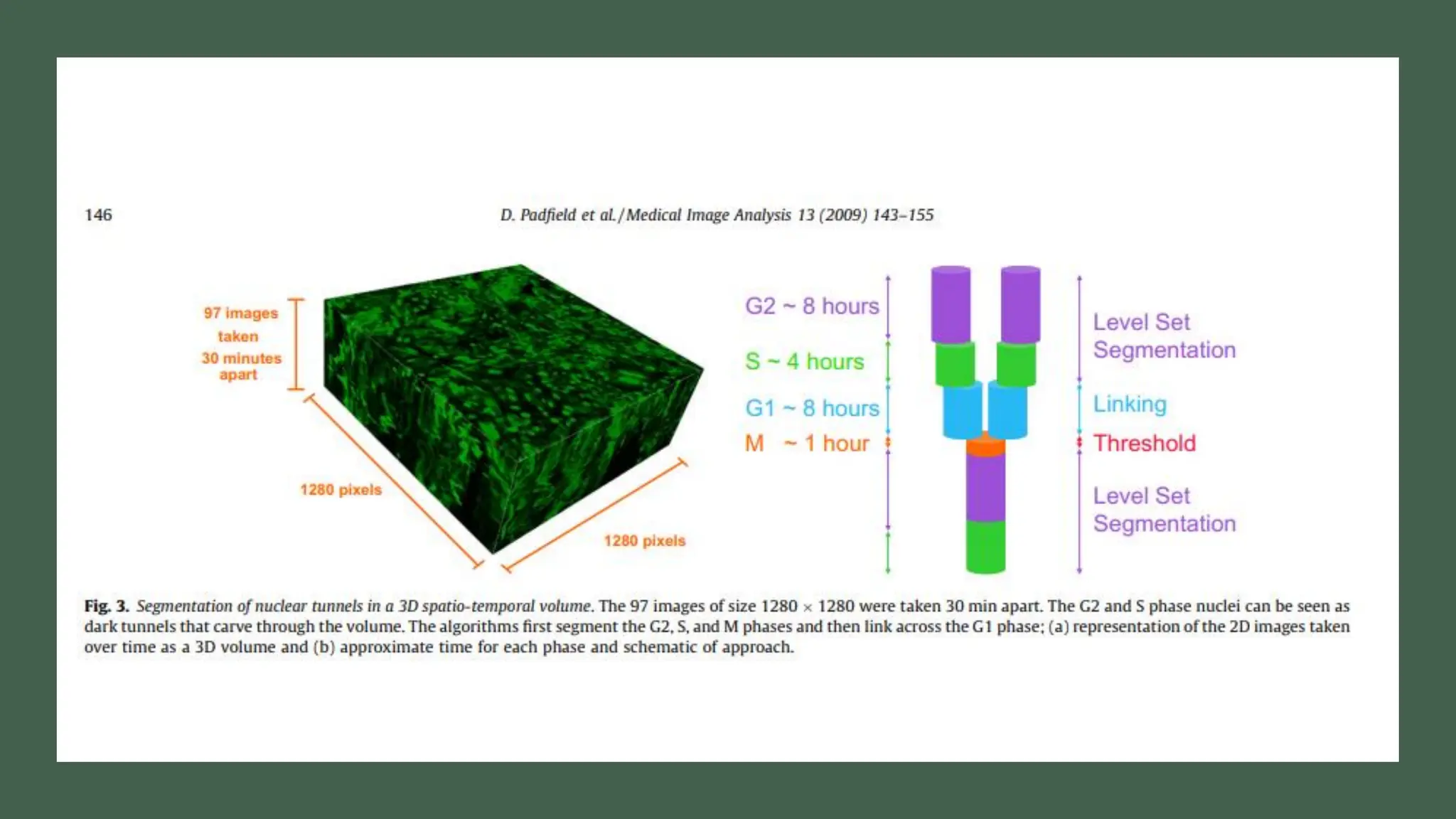

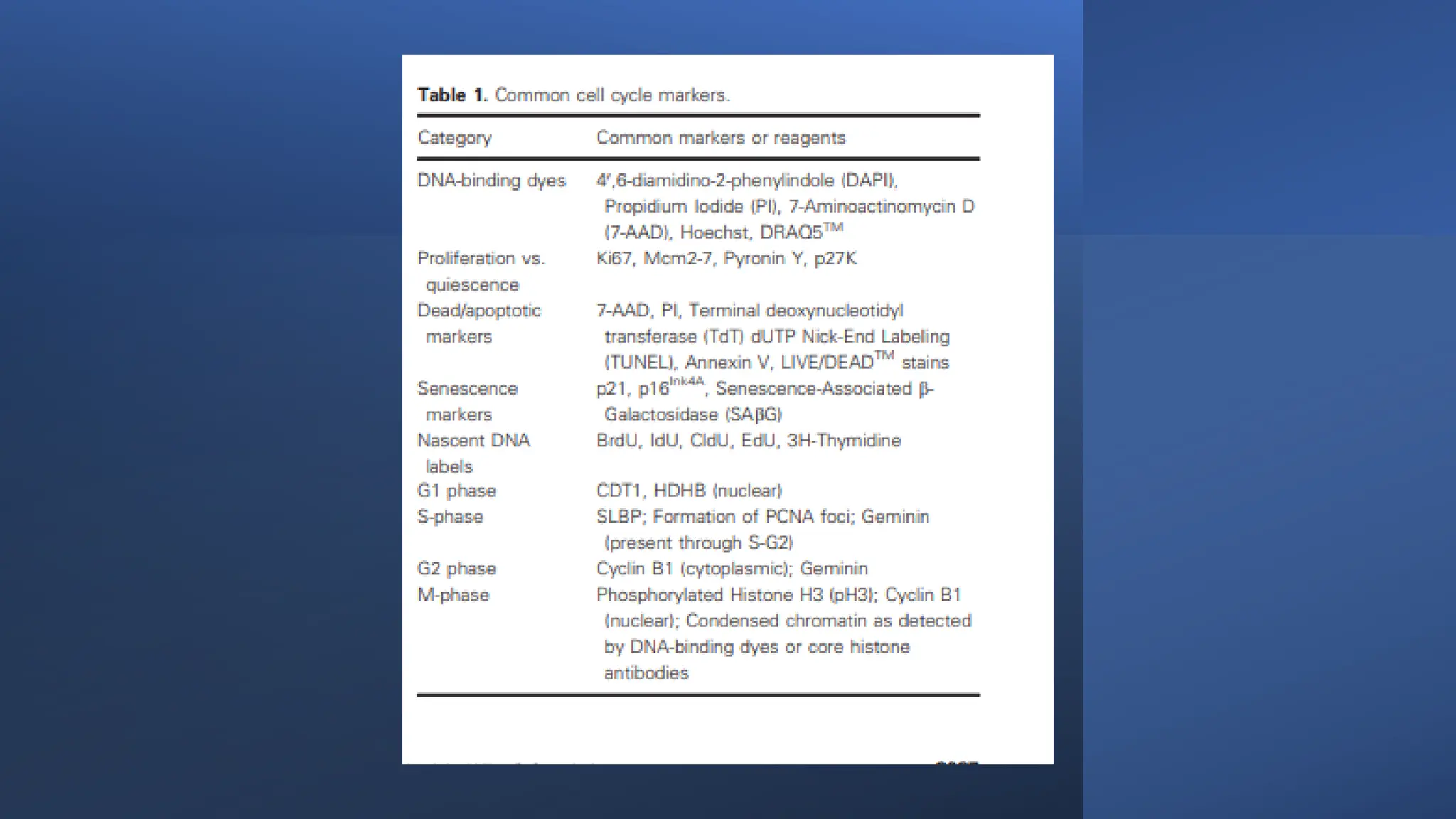

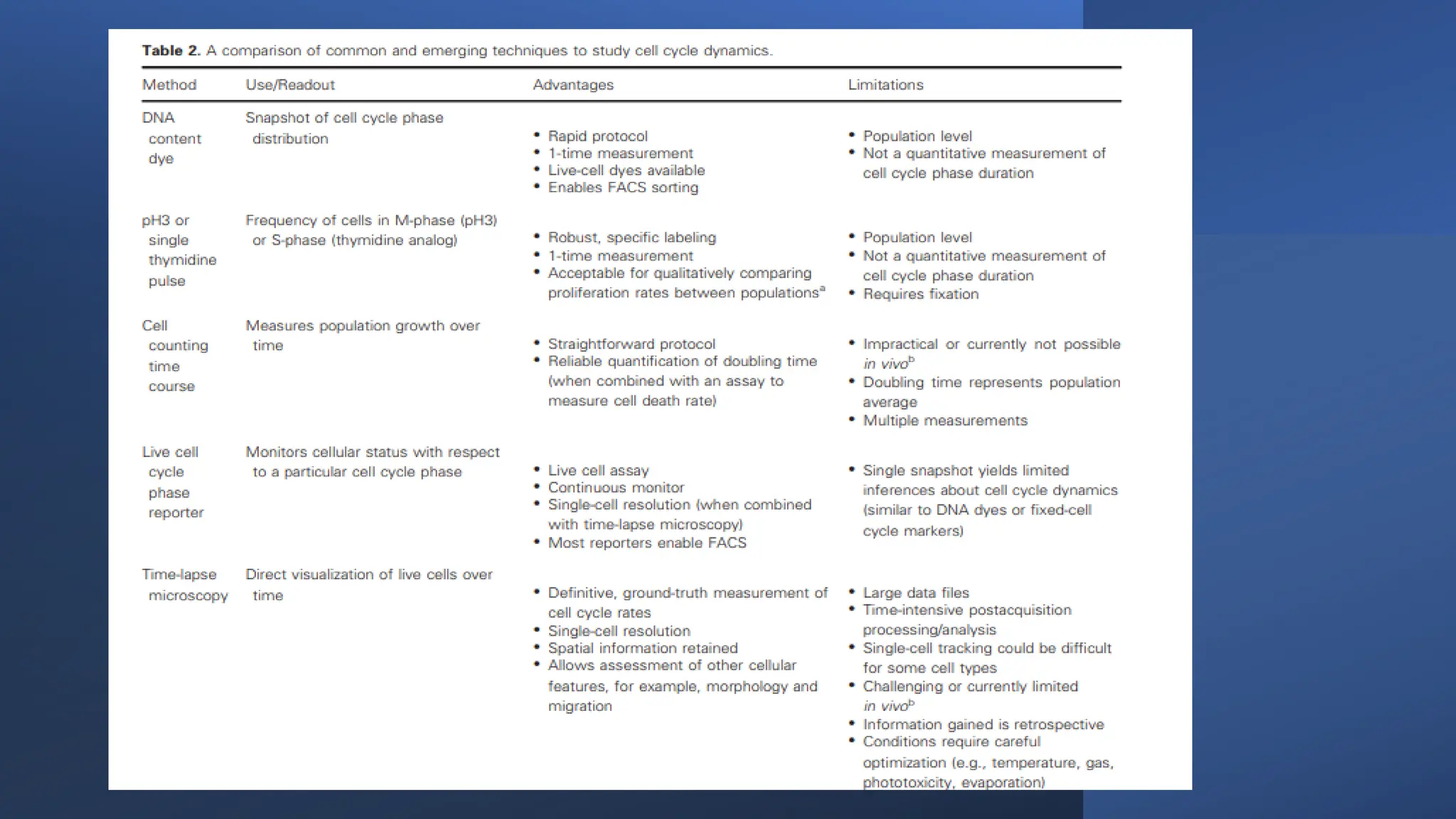

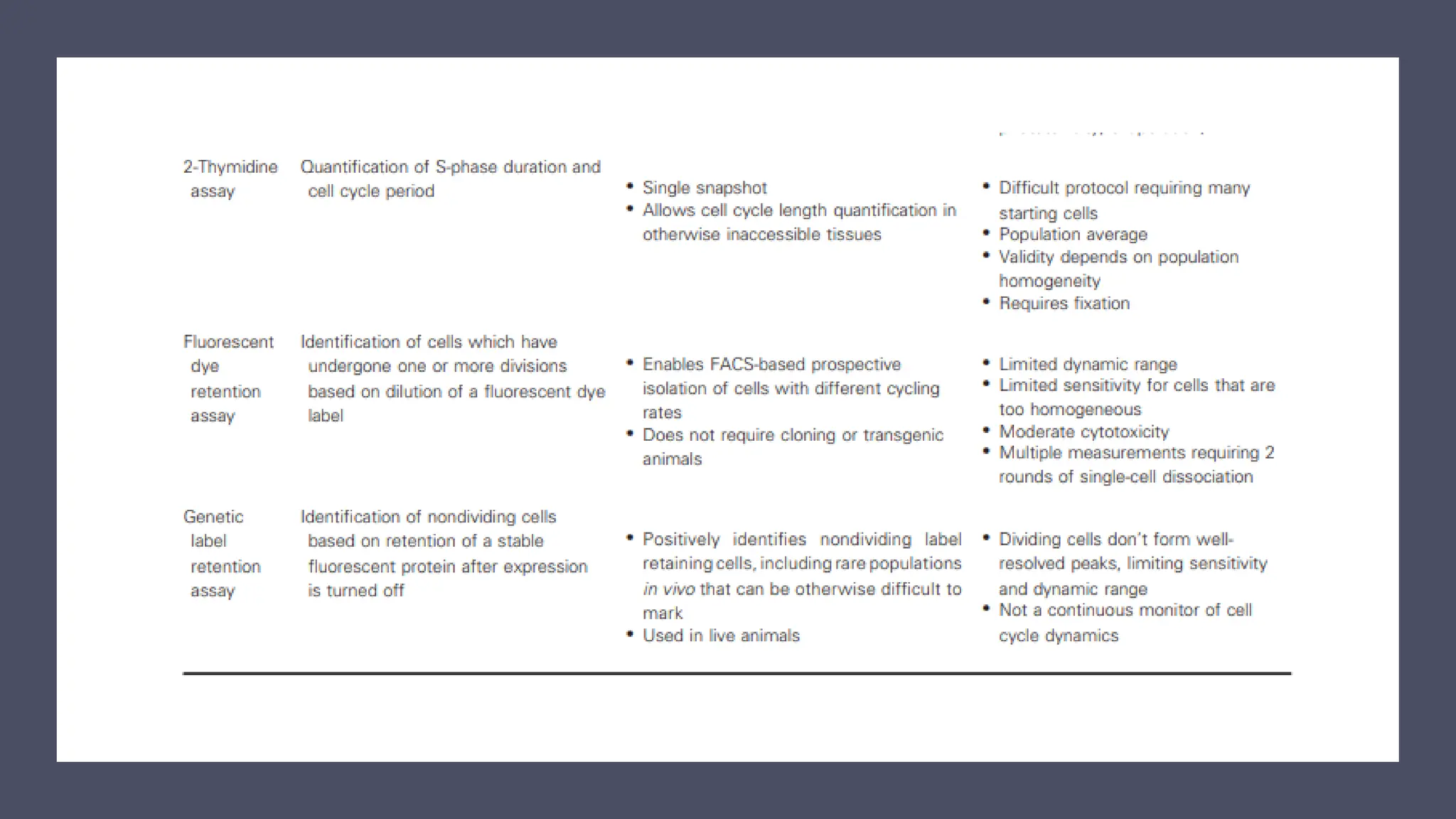

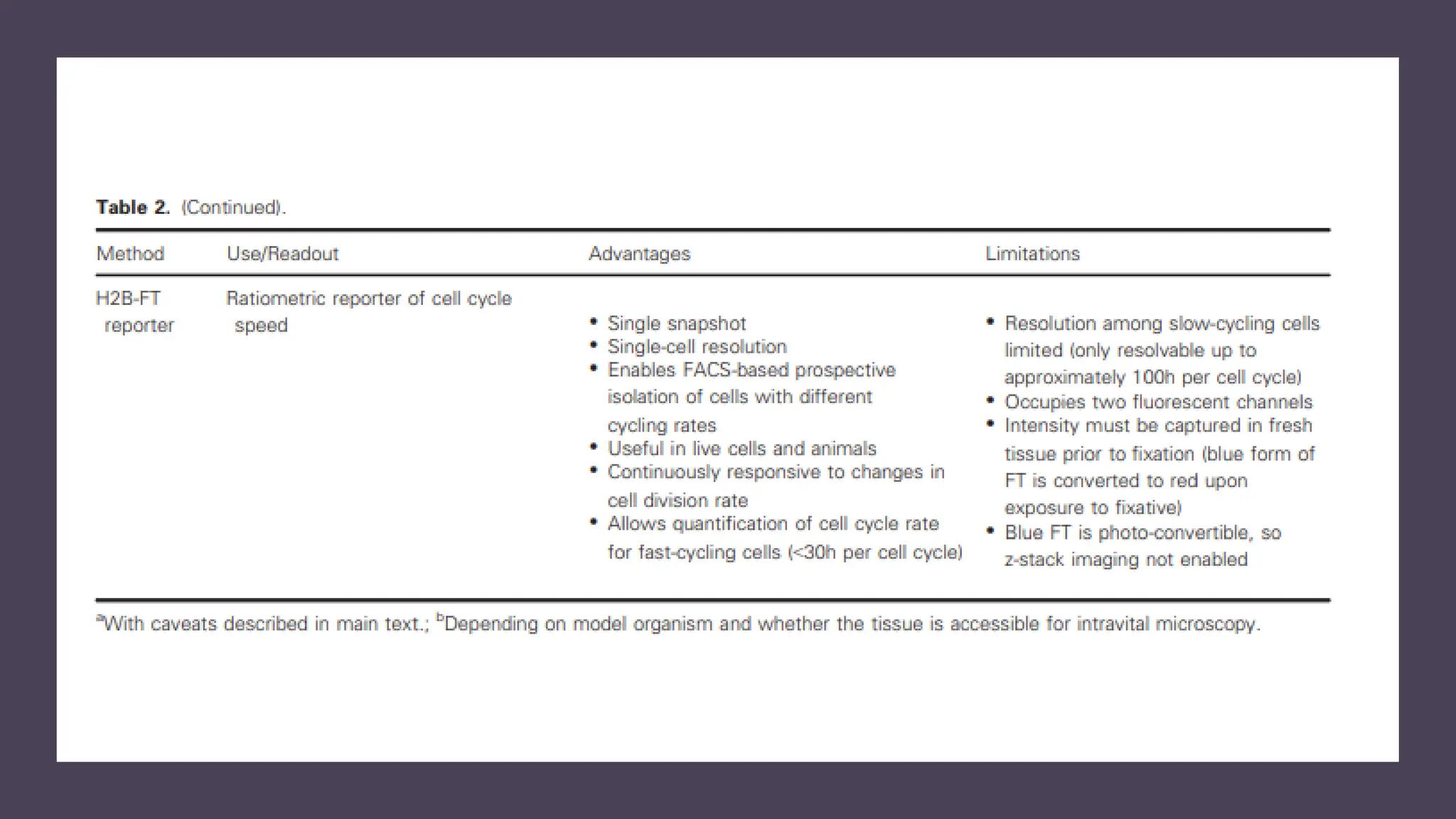

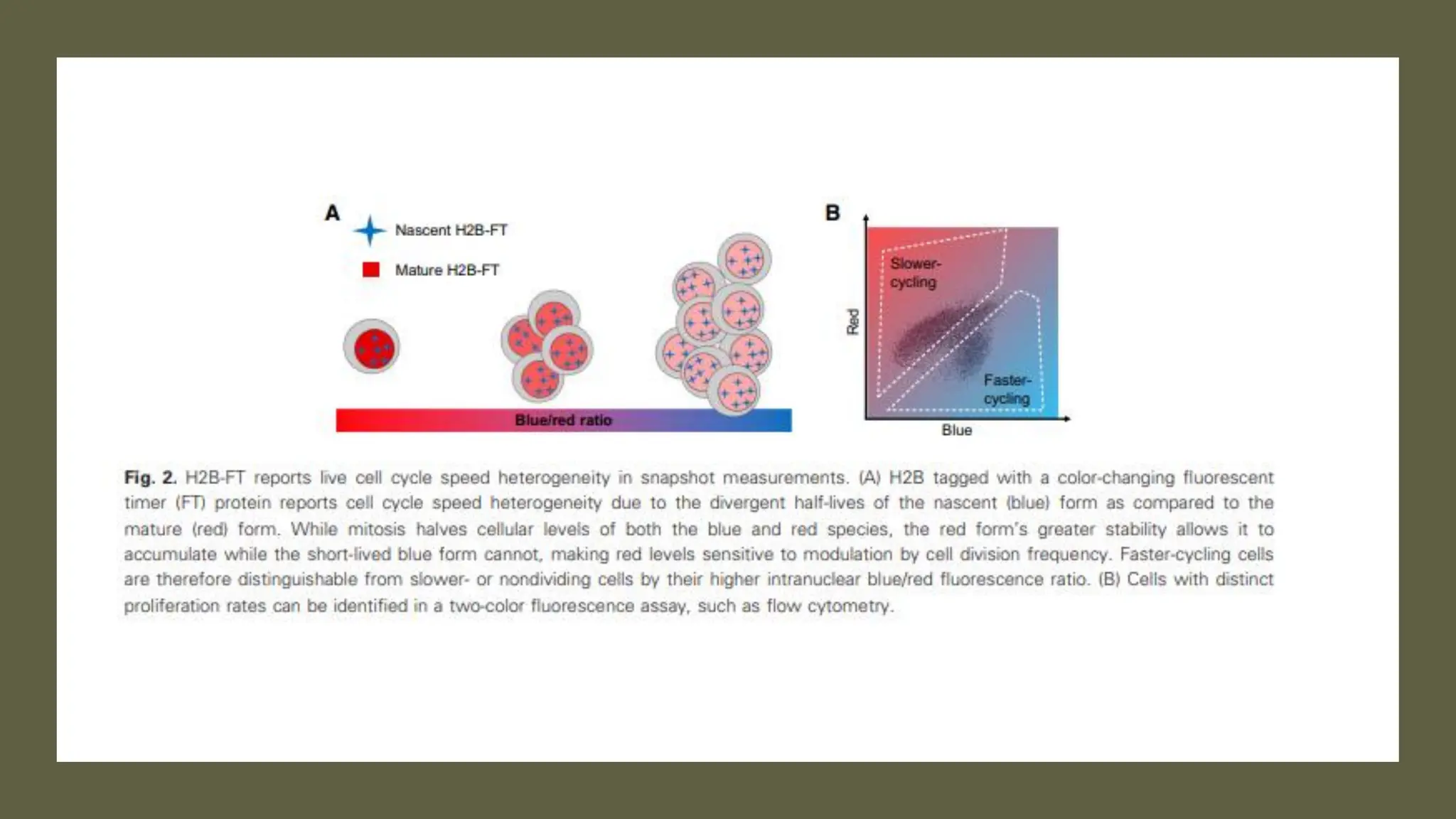

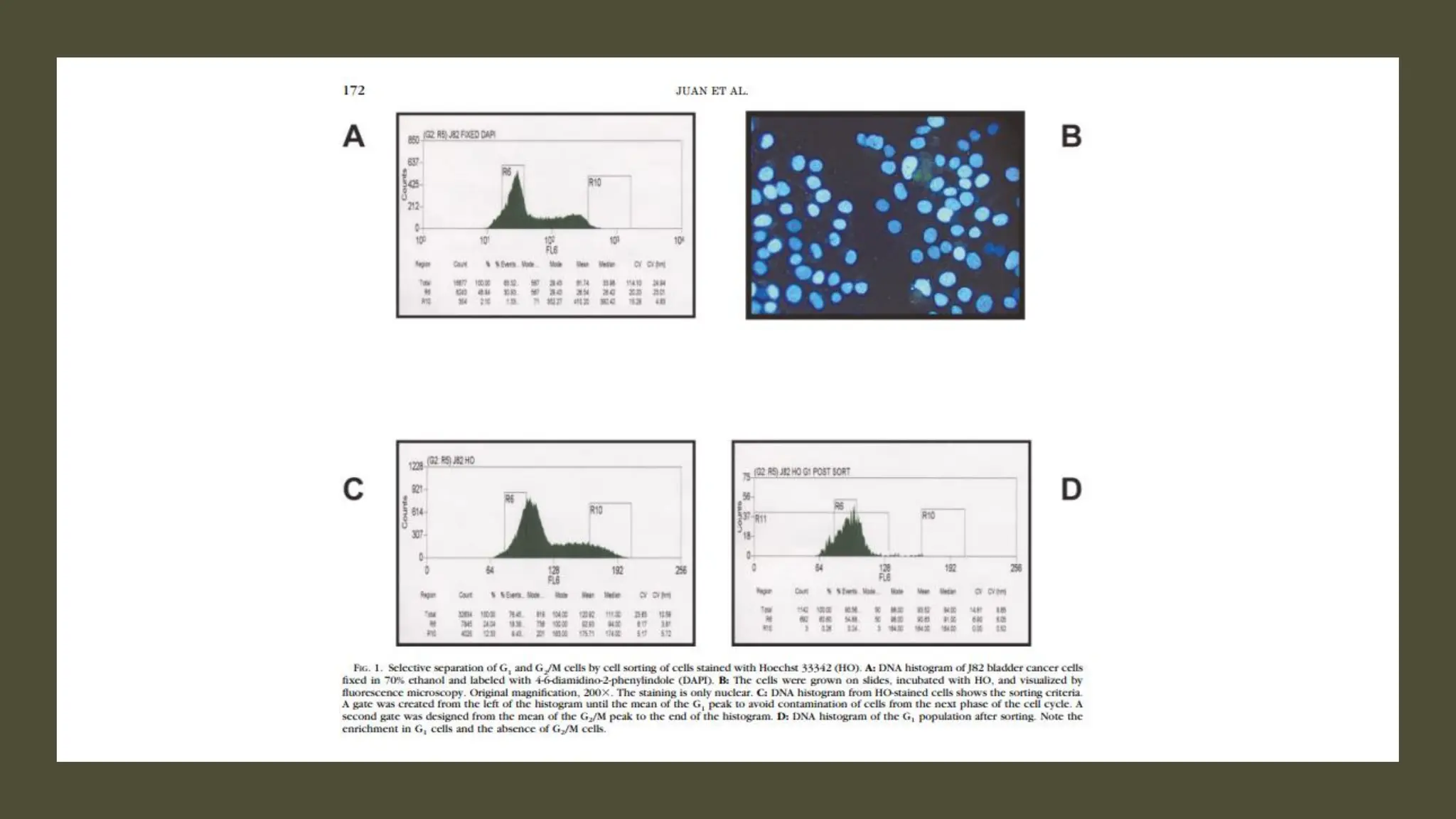

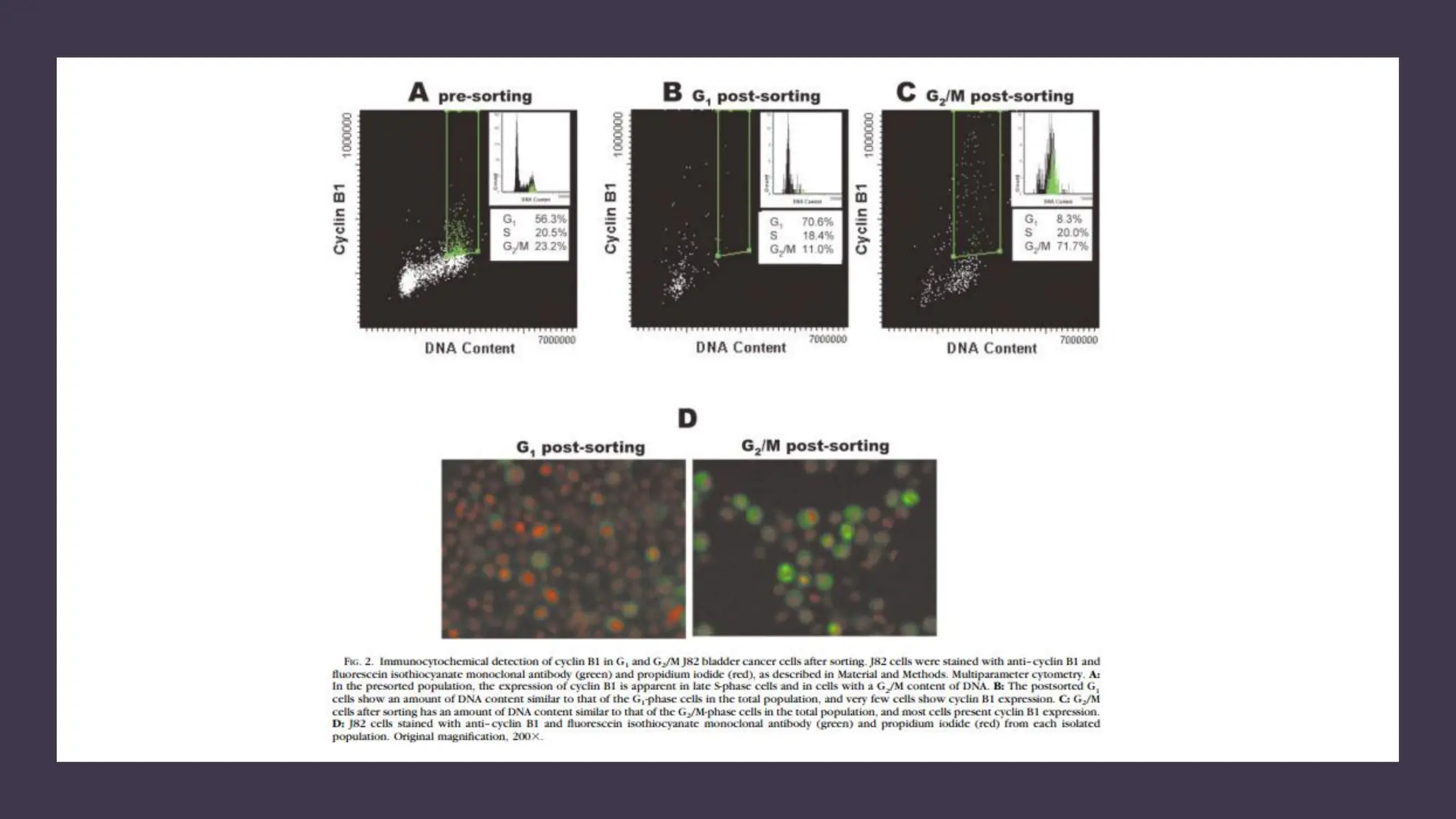

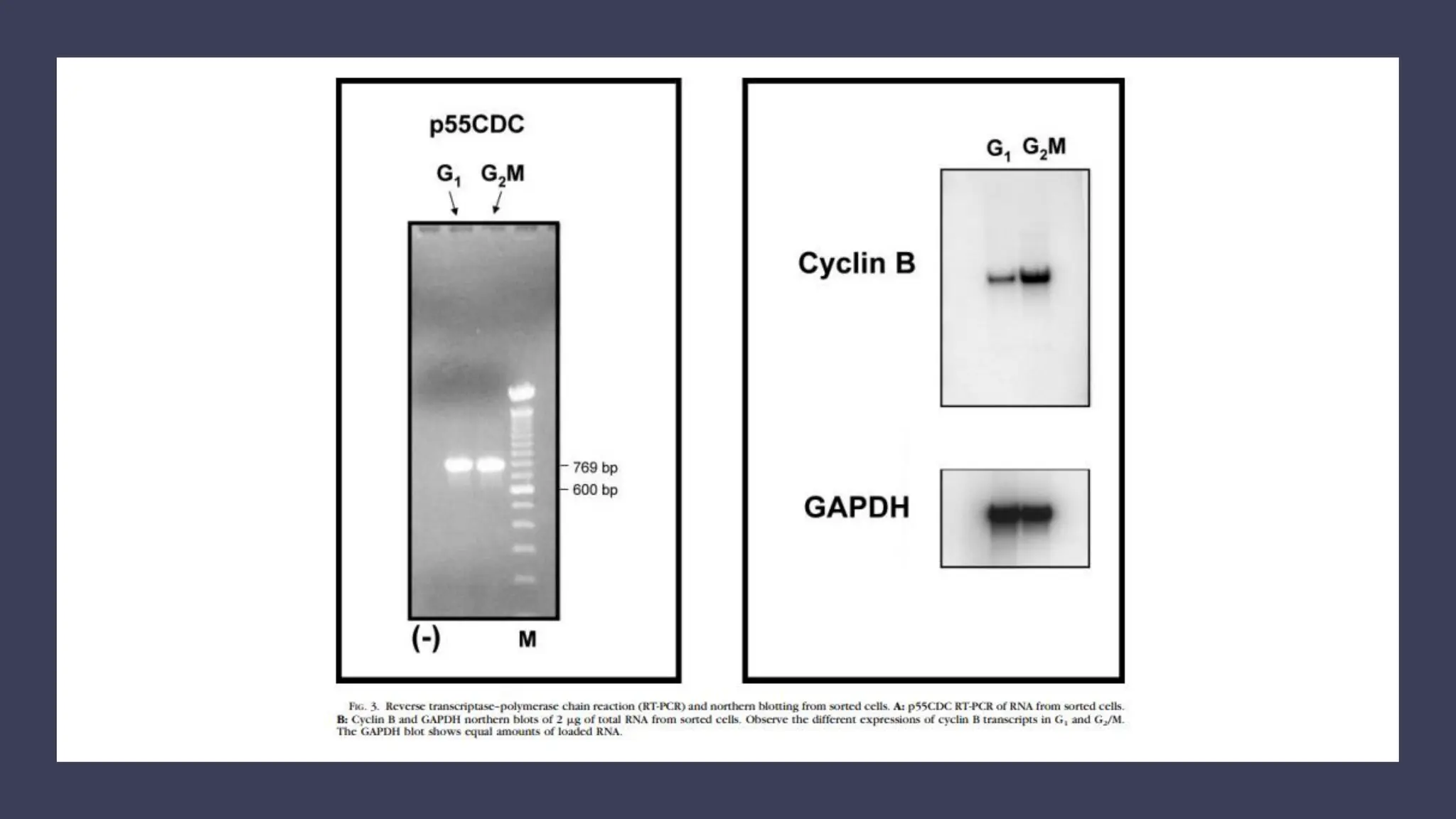

The document provides an overview of the cell cycle, detailing its phases (G1, S, G2, M), regulatory mechanisms involving cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and the consequences of dysregulation. It emphasizes the importance of cyclin-CDK complexes in regulating transitions between phases, particularly in response to growth factors. Additionally, it discusses the involvement of checkpoints in monitoring cell cycle progression and ensuring DNA damage is addressed or leads to apoptosis if necessary.