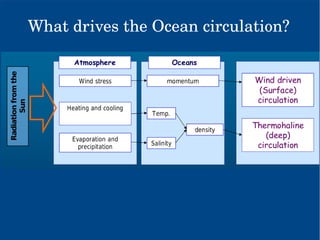

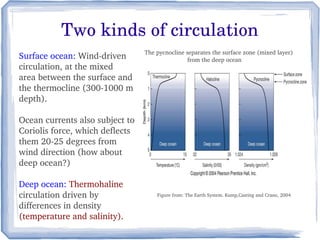

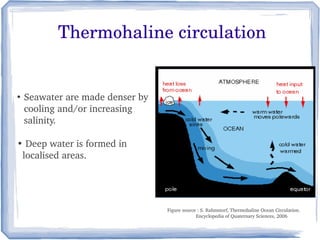

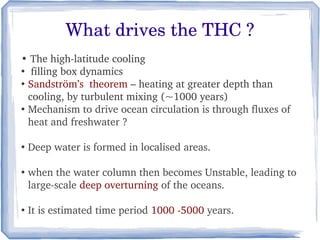

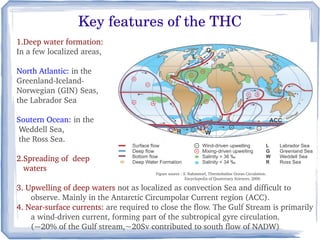

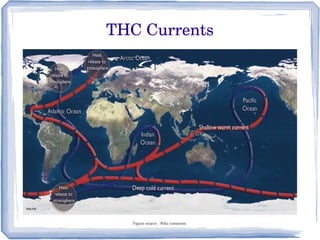

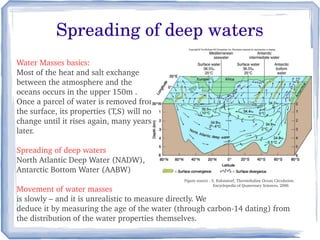

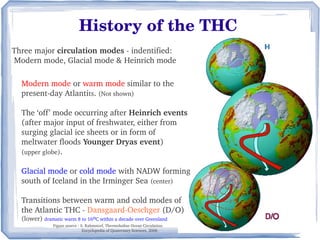

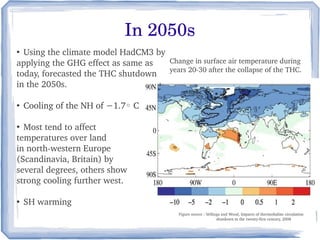

The document discusses the mechanisms and importance of thermohaline circulation (THC) in ocean and climate dynamics, explaining how it is driven by density differences due to temperature and salinity. It highlights the potential impacts of global warming on THC, predicting significant weakening in deep water formation, which could disrupt marine ecosystems and climate patterns by the 2050s. Historical modes of THC are also described, along with its role in climate regulation over various timescales.

![The future of the THC

Global warming can affect the THC in two ways:

surface warming and surface freshening, both reducing the density of

highlatitude surface waters & deep water formation.

Most models predict a significant weakening of NADW formation

(by 2050%) in response to anthropogenic global warming during the

21st century [IPCC, 2001]. Some also find a reduction in AABW

formation.

A major weakening or shutdown of NADW formation could have

serious impacts on marine ecosystems, sea level and surface climate,

including a shift in ITCZ & tropical rainfall belts.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thccc-121110111631-phpapp01/85/Thermohaline-Circulation-Climate-Change-12-320.jpg)

![References

[1] Wallace S. Broecker, James P . Kennett, Benjamin P. Flower, James T. Teller, Sue Trumbore,

Georges Bonani, and Willy Wolfli. Routing of meltwater from the laurentide ice sheet

during the younger dryas cold episode. Nature, 341(6240):318–321, September 1989.

[2] Peter U. Clark, Nicklas G. Pisias, Thomas F. Stocker, and Andrew J. Weaver. The role of

the thermohaline circulation in abrupt climate change. Nature, 415(6874):863–869,

February 2002.

[3] J. F. McManus, R. Francois, J. M. Gherardi, L. D. Keigwin, and S. BrownLeger. Collapse

and rapid resumption of atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate

changes. Nature, 428(6985):834–837, April 2004.

[4] Michael Vellinga and RichardA Wood. Impacts of thermohaline circulation shutdown in

the twentyfirst century. Climatic Change , 91(12):43–63+, 2008.

[5] S. Rahmstorf, S. A. Elias. Elsevier and Amsterdam. Thermohaline Ocean Circulation.

Encyclopedia of Quaternary Sciences, 2006.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thccc-121110111631-phpapp01/85/Thermohaline-Circulation-Climate-Change-17-320.jpg)