The document discusses how the ocean affects climate through various mechanisms:

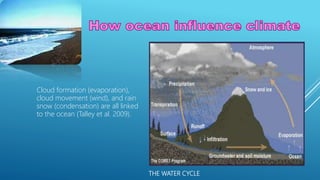

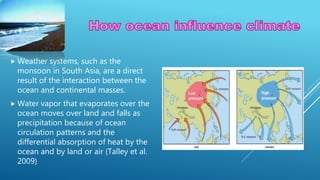

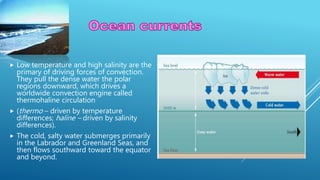

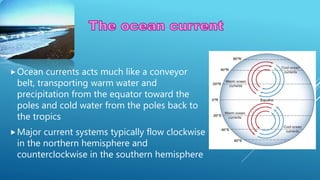

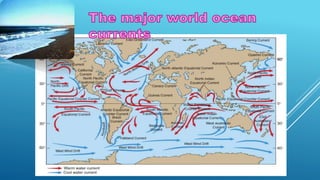

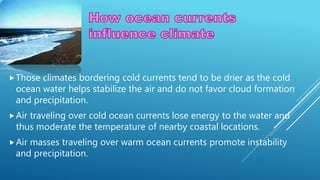

1) It regulates global temperature by storing and transporting heat around the globe via currents and influences wind and precipitation patterns.

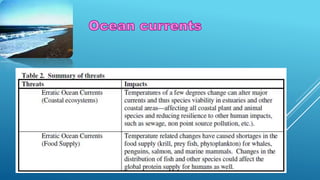

2) Ocean currents stabilize climate in coastal regions and bring nutrients to marine environments.

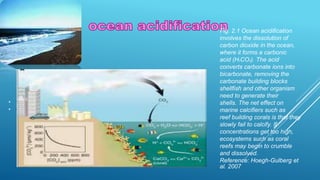

3) The ocean cycles gases by absorbing large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

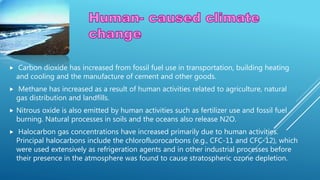

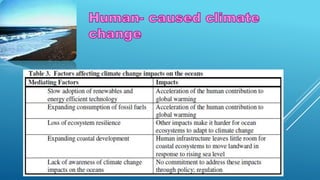

4) Human activities like greenhouse gas emissions and land use changes are altering the climate system.