1. The document discusses how children acquire their first language without direct instruction, instead constructing language through interactions.

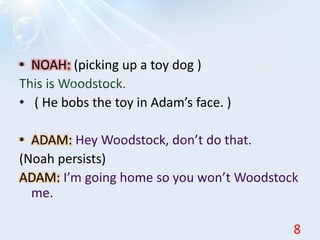

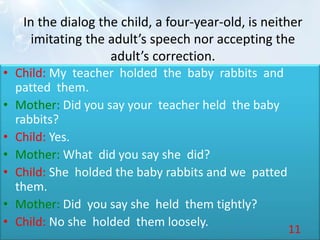

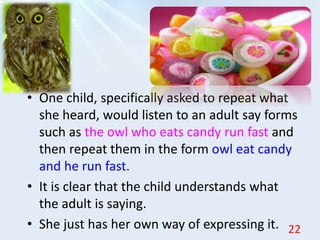

2. Children do not simply imitate adult speech but actively test out their own constructions. Adults also do not produce all the expressions children use.

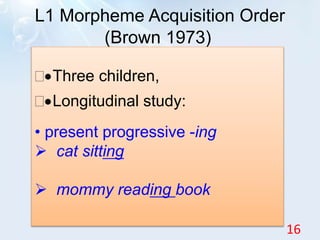

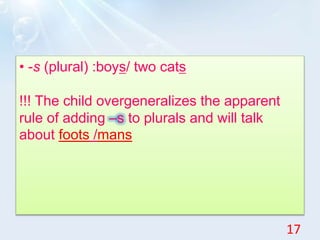

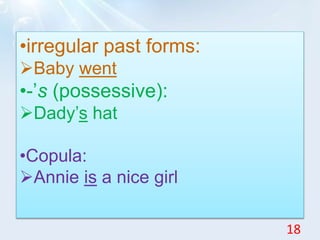

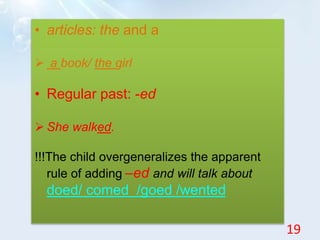

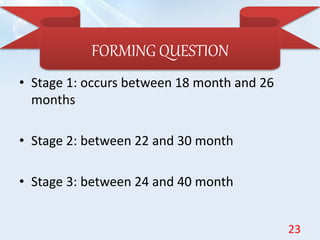

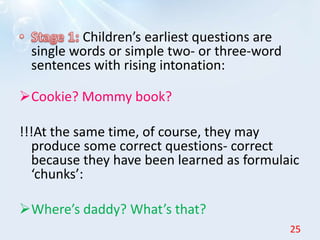

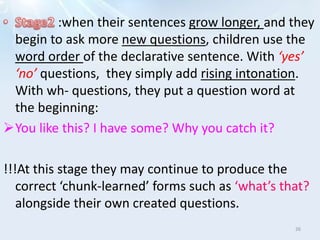

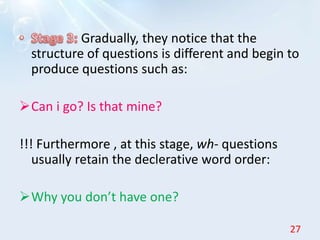

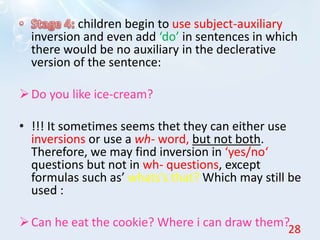

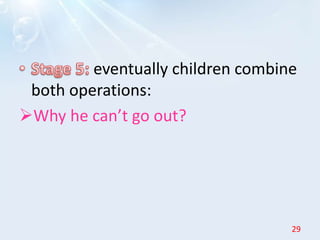

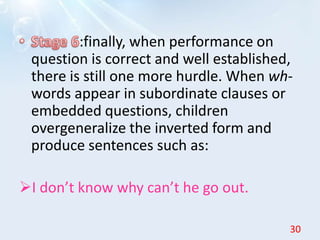

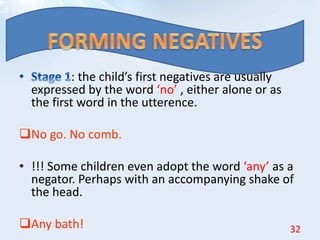

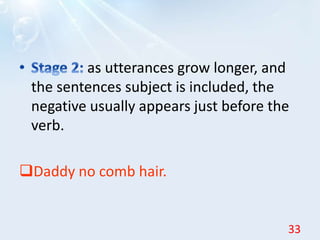

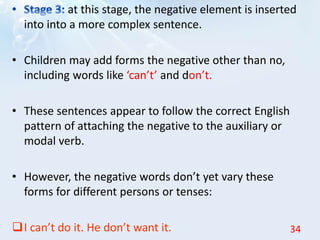

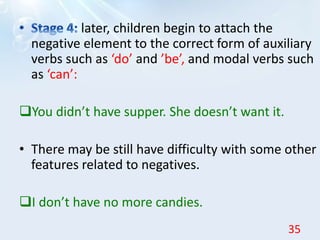

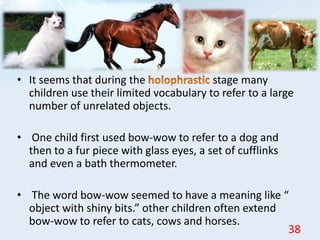

3. As children's language develops, they begin incorporating morphological and syntactic structures like plurals, past tense, questions and negatives in their own way before fully mastering conventions. Their meanings for words may also be broader than adults'.