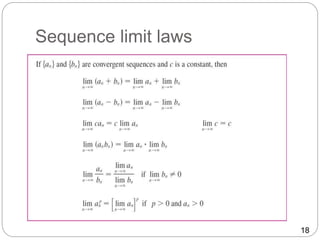

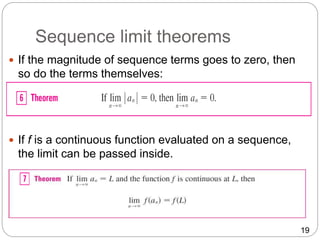

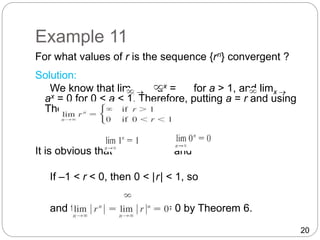

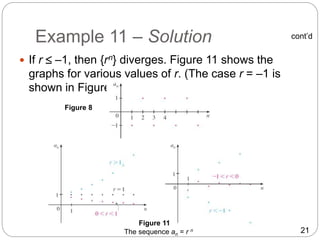

This document discusses sequences and their limits. Some key points:

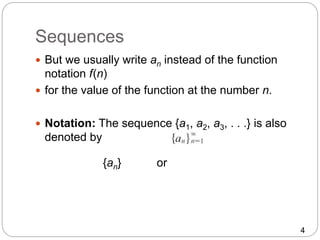

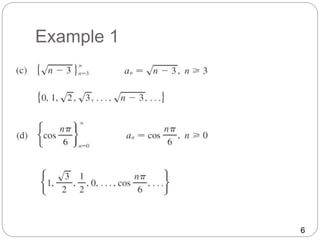

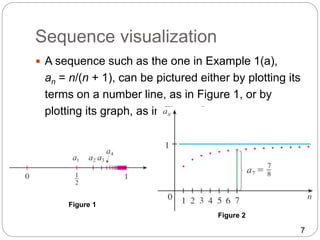

- A sequence is a list of numbers written in a definite order. It can be thought of as a function with domain the positive integers.

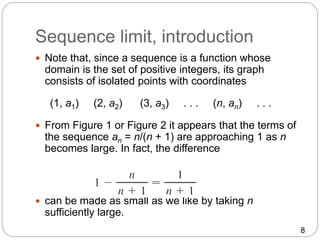

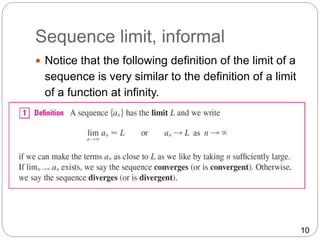

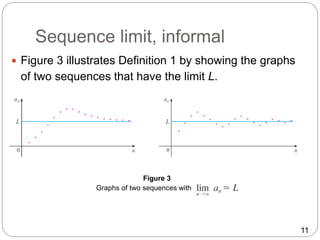

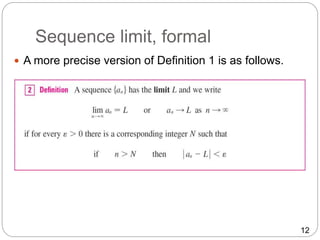

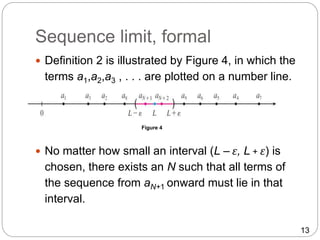

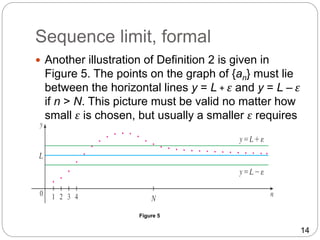

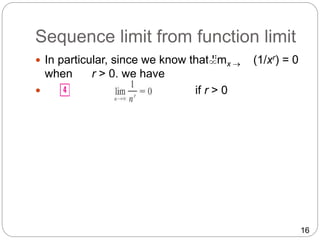

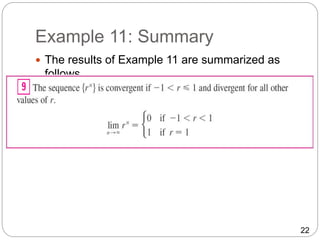

- The limit of a sequence is defined similar to the limit of a function. The limit of a sequence {an} as n approaches infinity is L if the terms can be made arbitrarily close to L by making n sufficiently large.

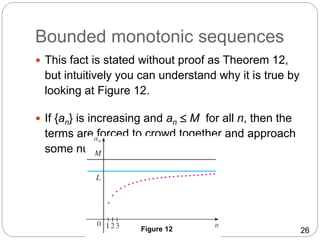

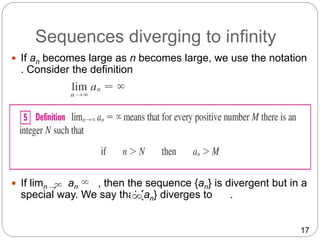

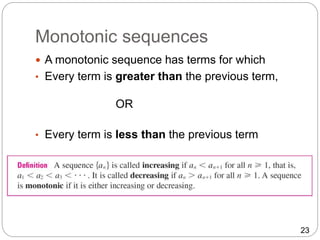

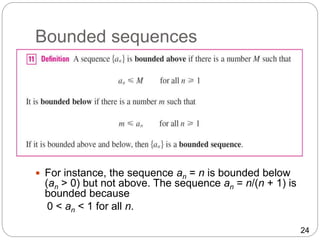

- A sequence is convergent if it approaches a finite limit. It is divergent if the terms approach infinity. Bounded monotonic sequences are always convergent due to the completeness of real numbers.

![25

Bounded monotonic sequences

We know that not every bounded sequence is

convergent [for instance, the sequence an = (–1)n

satisfies –1 an 1 but is divergent,] and not

every monotonic sequence is convergent (an = n

).

But if a sequence is both bounded and

monotonic, then it must be convergent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sequencesandseries-191029120854/85/Sequences-and-series-25-320.jpg)