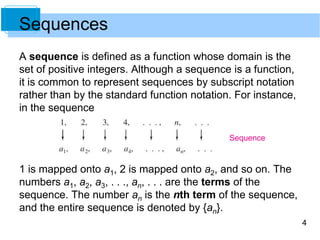

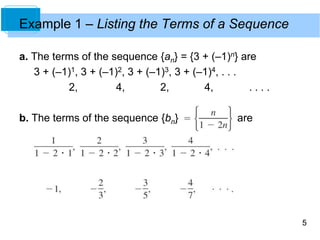

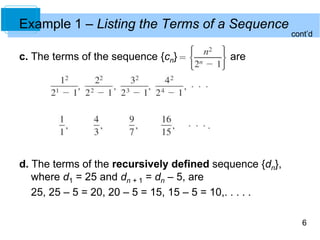

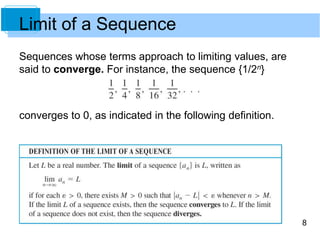

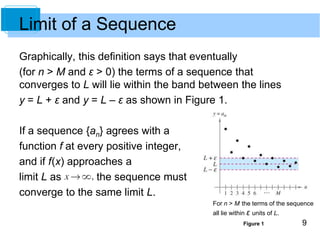

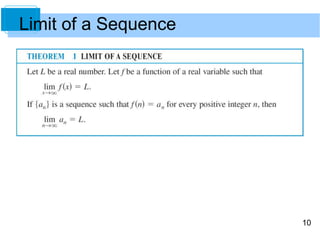

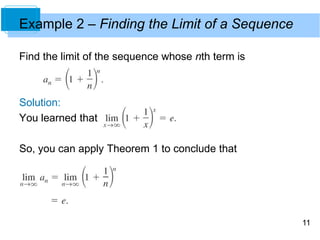

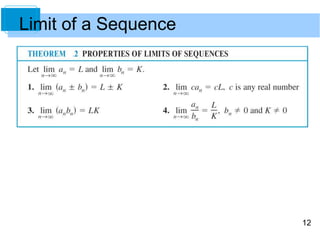

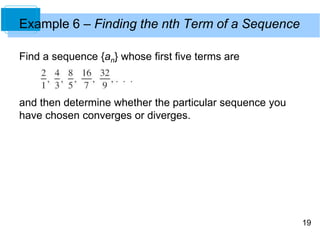

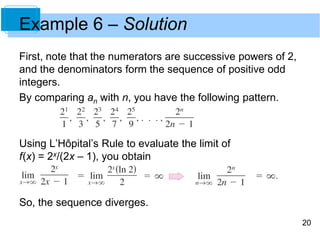

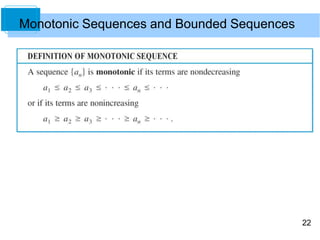

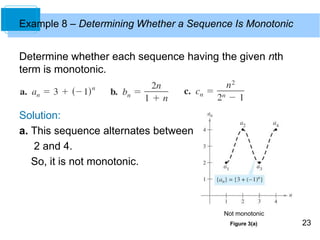

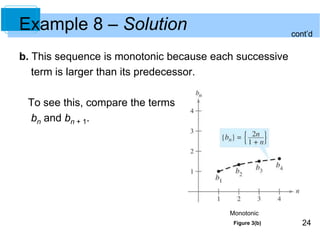

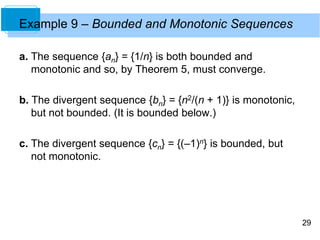

The document discusses sequences and their properties. A sequence is a function whose domain is the positive integers. Sequences are commonly represented using subscript notation rather than standard function notation. The nth term of a sequence is denoted an. [/SUMMARY]