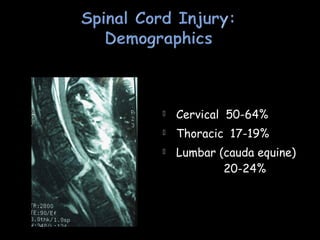

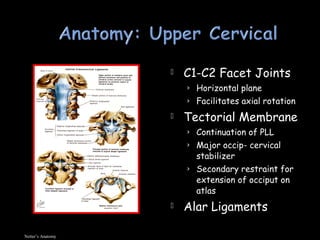

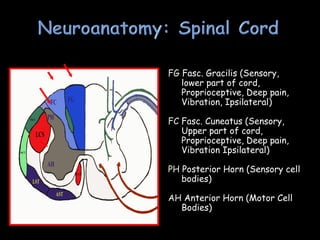

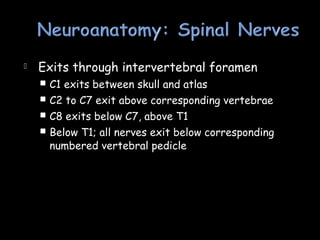

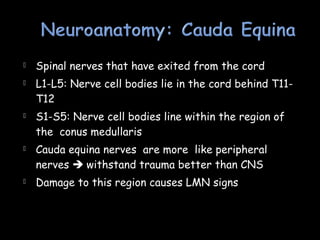

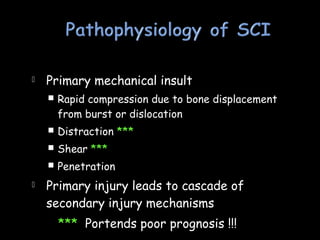

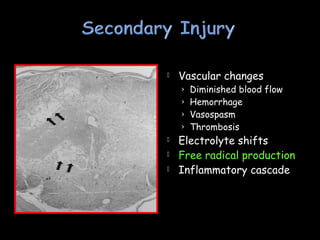

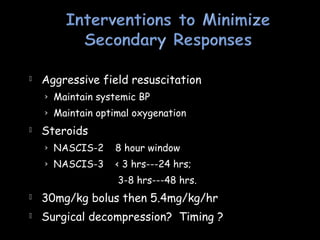

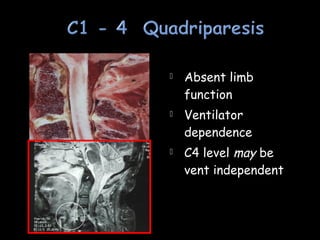

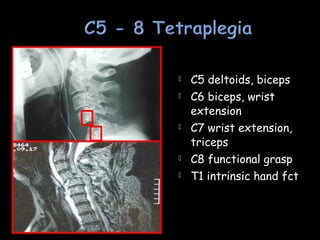

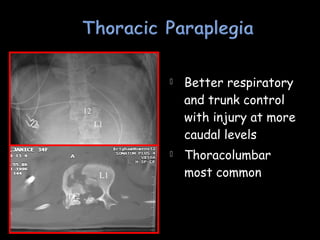

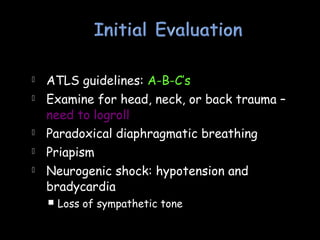

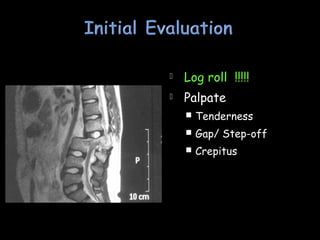

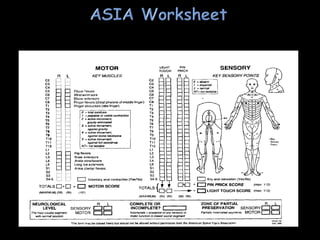

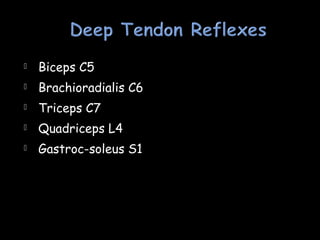

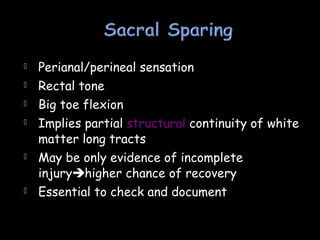

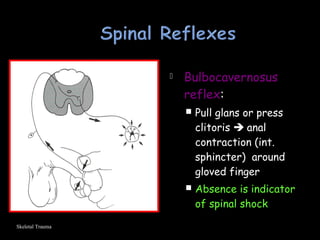

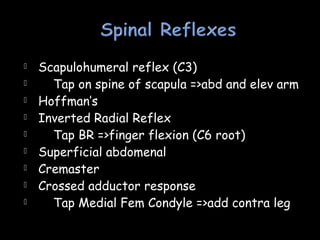

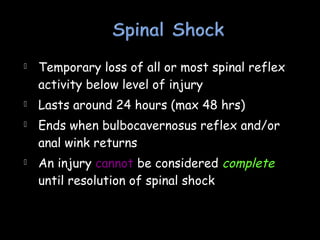

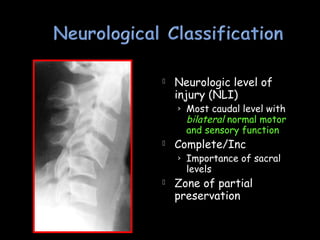

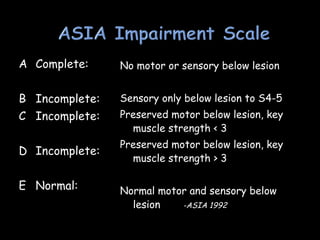

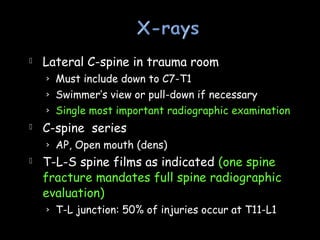

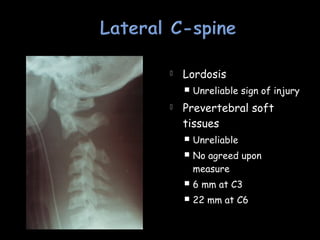

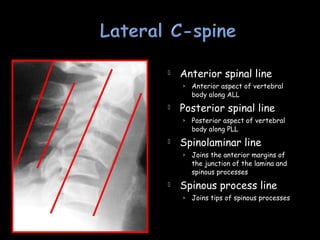

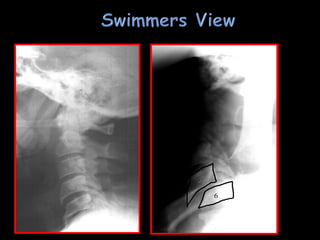

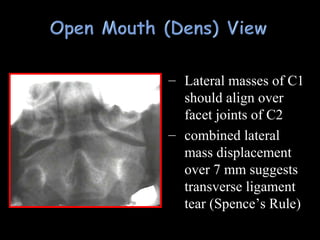

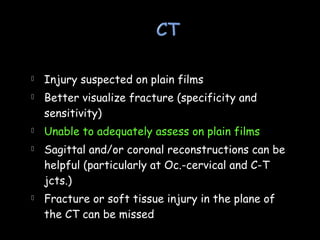

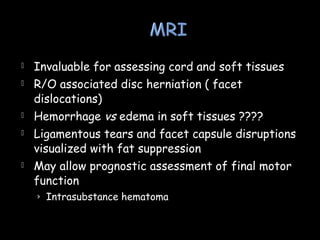

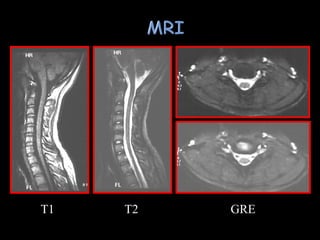

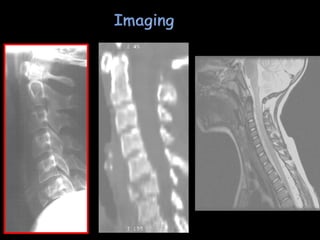

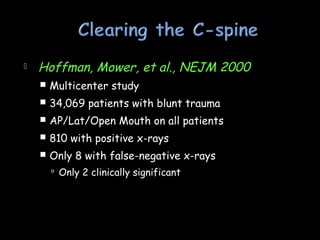

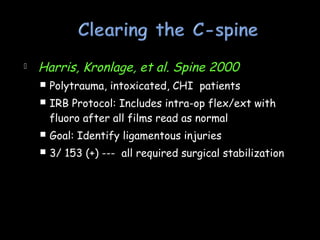

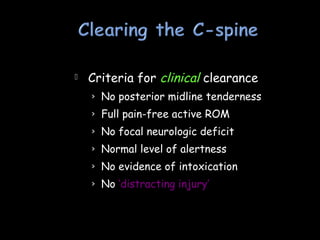

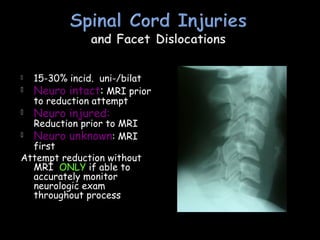

The document provides information on spinal cord and cervical spine anatomy, mechanisms of spinal cord injury, clinical assessment of spinal cord injury patients, imaging for spinal cord injuries, classification of spinal cord injuries, and management principles for spinal cord injuries. Key points covered include the incidence of spinal cord injuries, common mechanisms and levels of injury, assessment of motor and sensory function, classification systems for incomplete versus complete injuries, and guidelines for cervical spine clearance in trauma patients.