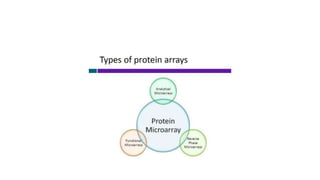

Proteomics is the study of the complete set of proteins expressed in an organism under particular conditions. It aims to understand protein expression in response to changing conditions like disease. Tools in proteomics include cell lysis, fractionation, protein concentration and quantification, digestion, and peptide cleanup prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Key techniques discussed are molecular techniques like SAGE, separation techniques like gel electrophoresis and chromatography, and protein identification techniques like mass spectrometry.