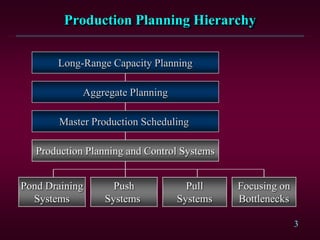

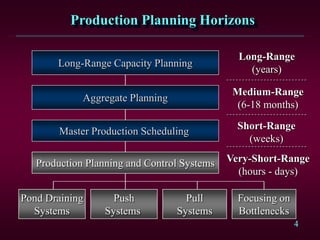

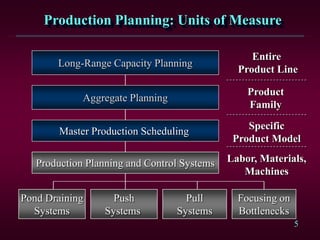

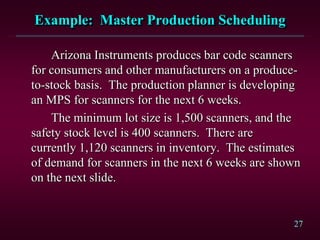

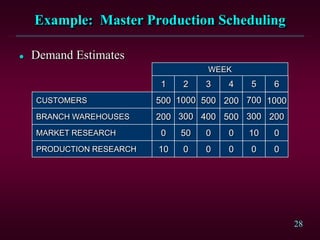

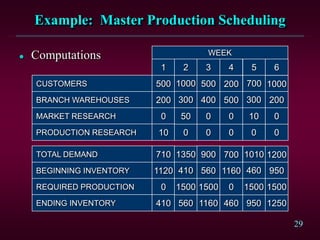

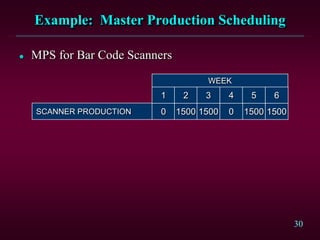

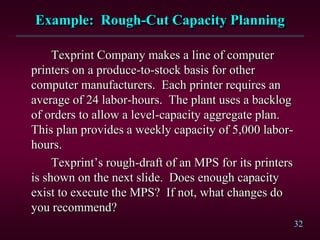

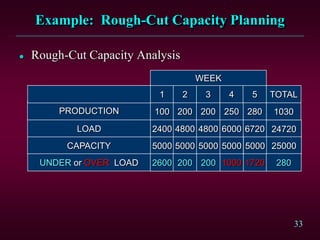

This document discusses production planning concepts including the production planning hierarchy, aggregate planning, master production scheduling, and types of production planning and control systems. It provides information on aggregate planning inputs and outputs, approaches to aggregate planning, and examples of developing a master production schedule and rough-cut capacity plan. It also describes different types of production planning systems such as pond draining, push, pull, and bottleneck-focused systems.