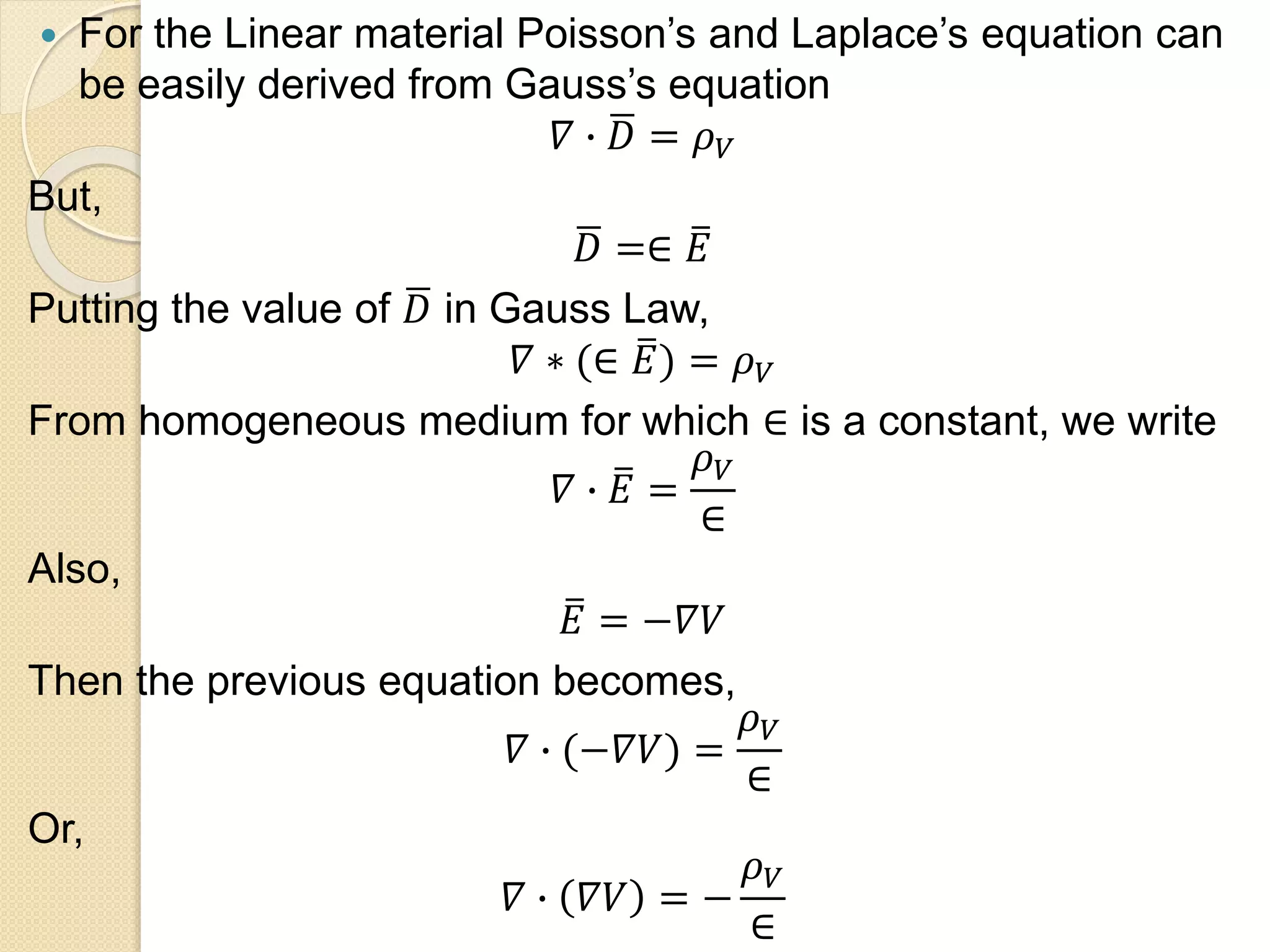

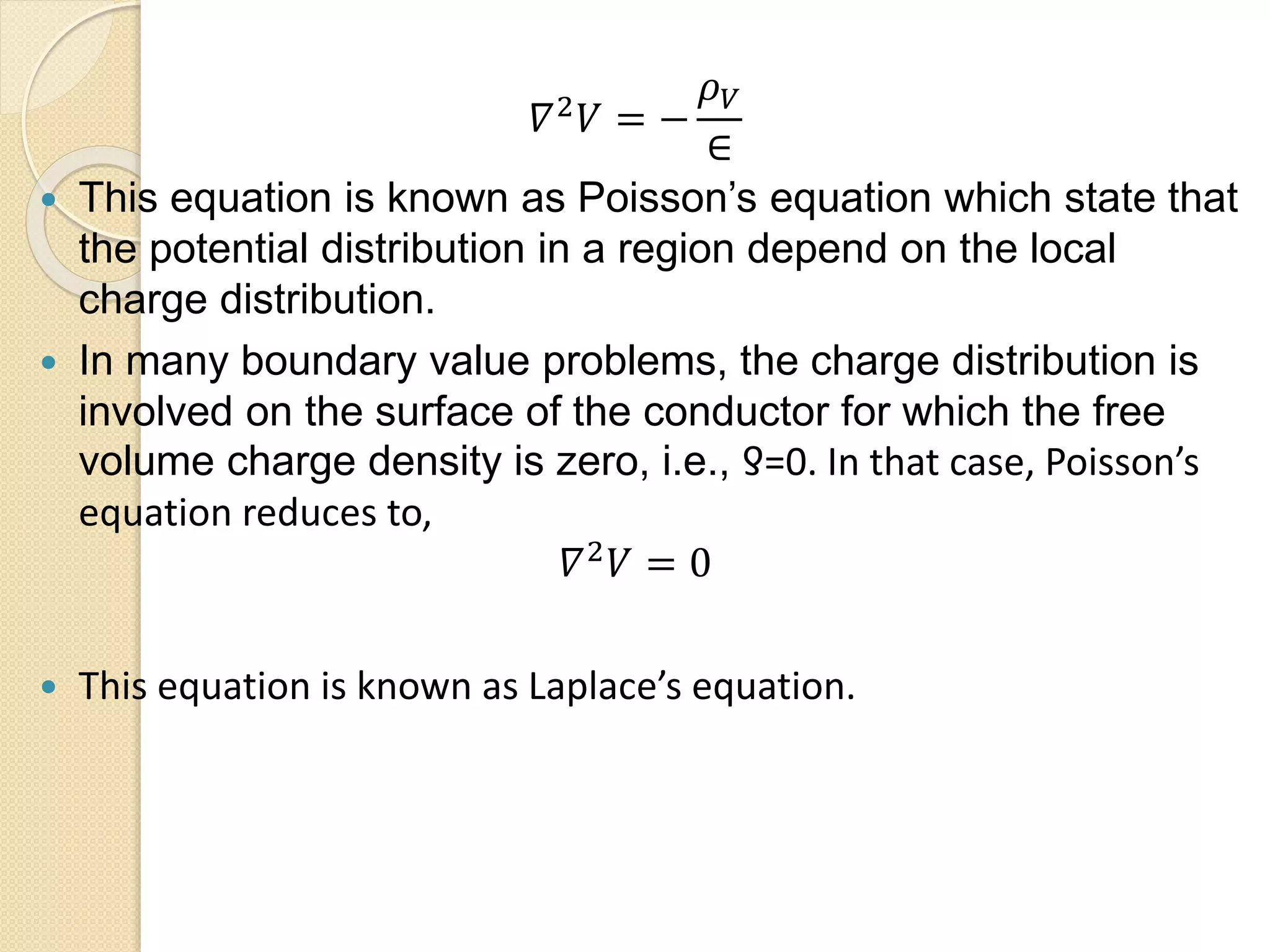

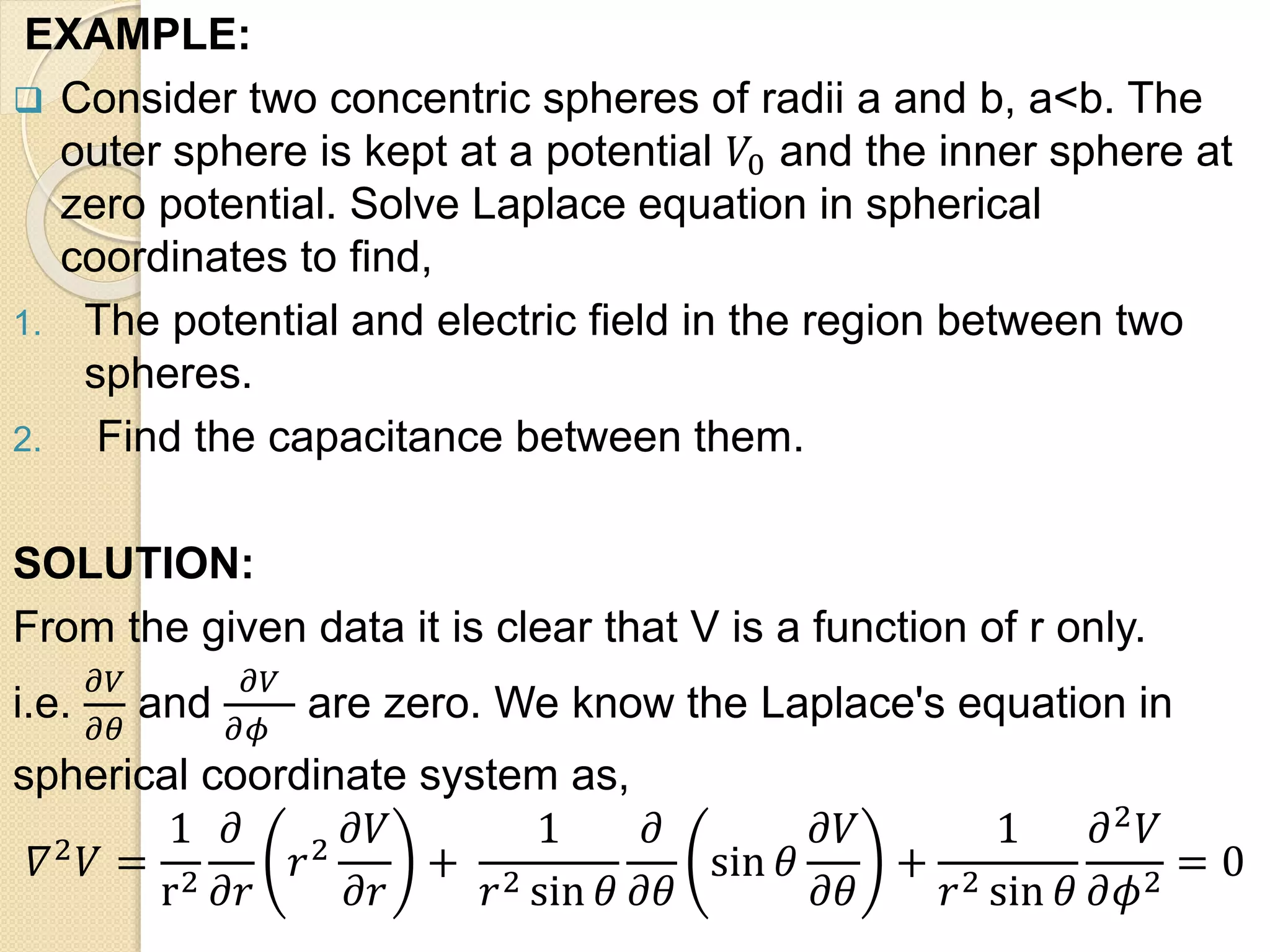

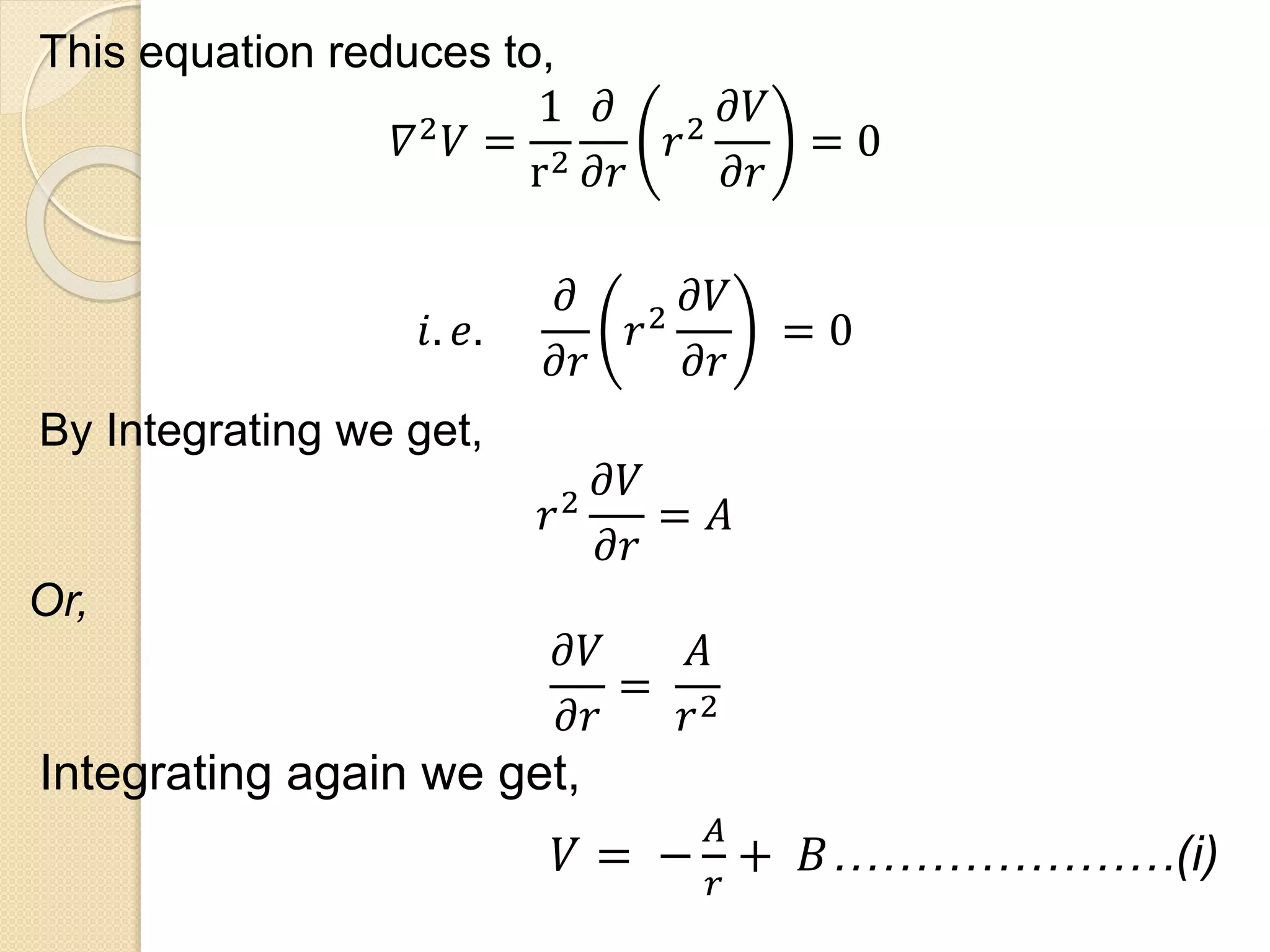

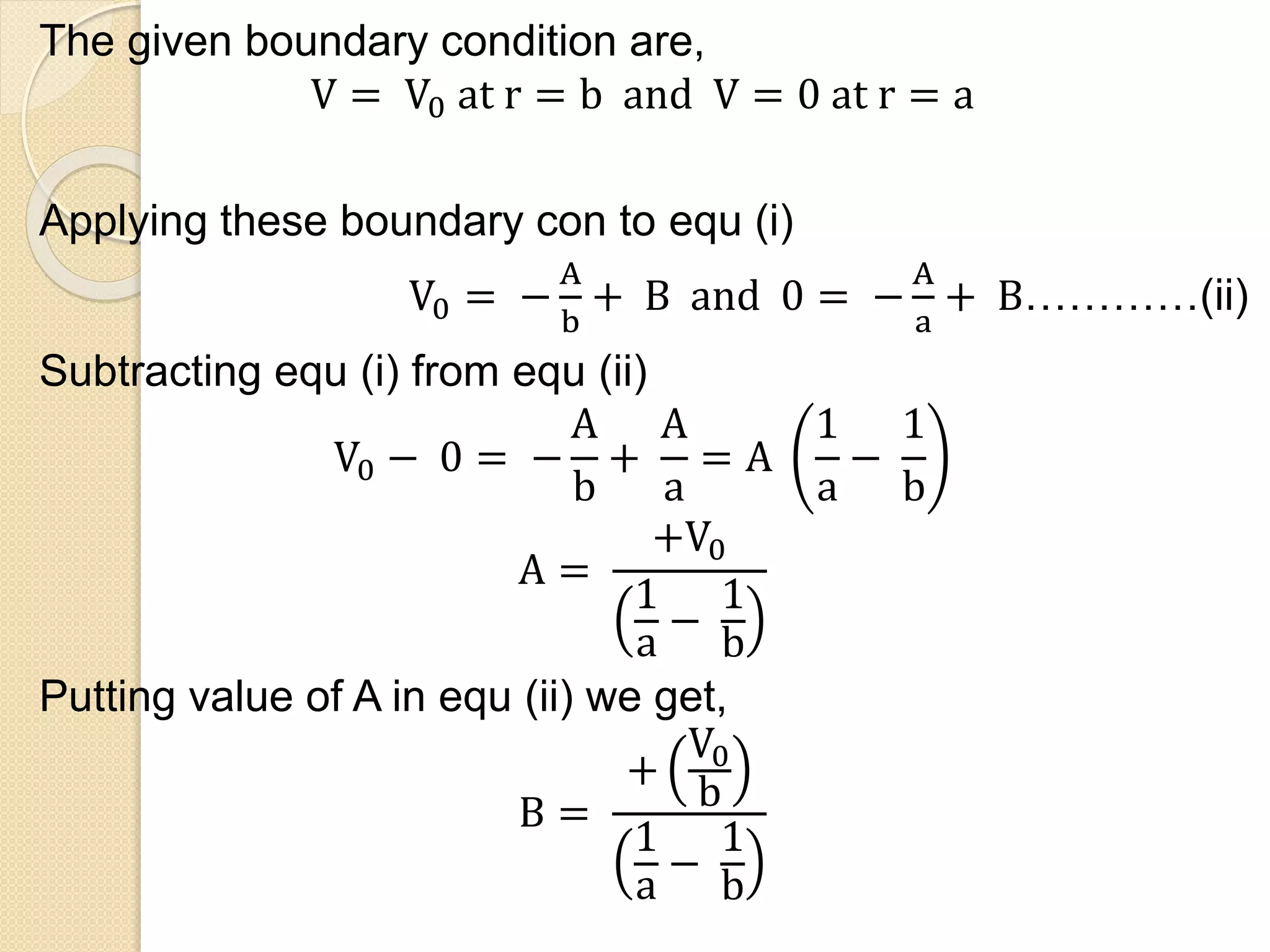

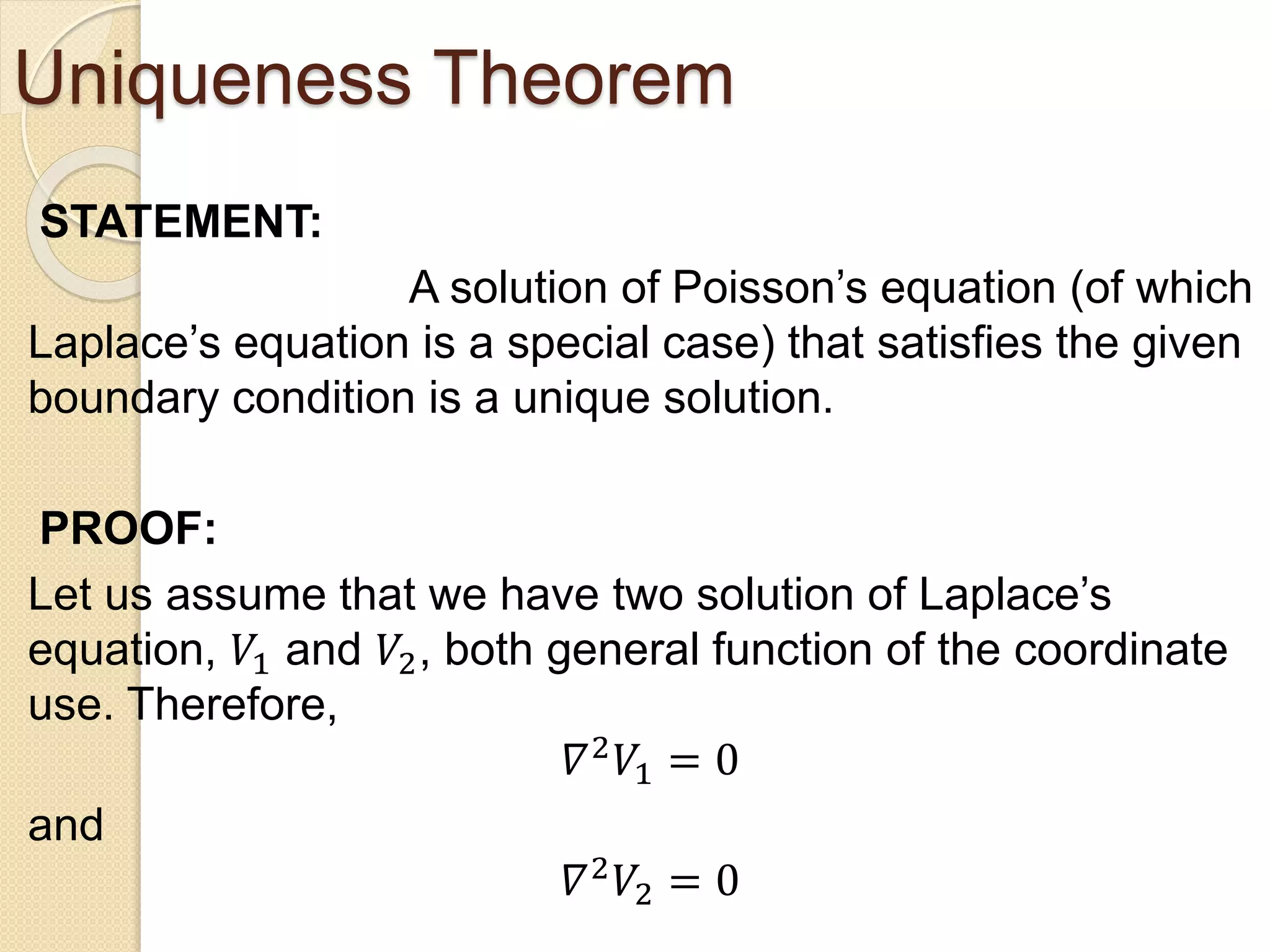

This document discusses Poisson's and Laplace's equations in the context of a class on field theory taught by Prof. Supraja. It provides definitions and derivations of Poisson's and Laplace's equations in different coordinate systems. It gives examples of using these equations to find electric potential and field between charged surfaces, as well as the capacitance between them. It also states the uniqueness theorem, which guarantees a unique solution to Laplace's/Poisson's equation given the boundary conditions.