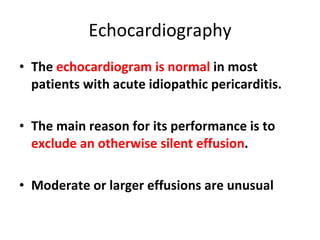

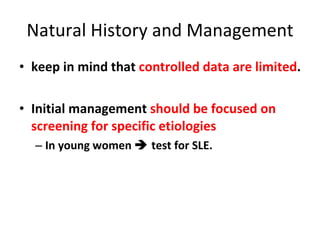

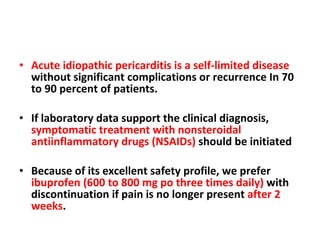

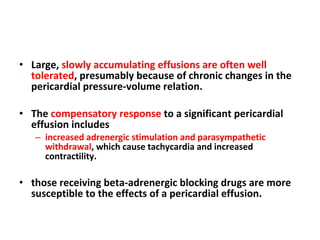

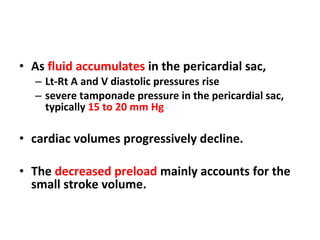

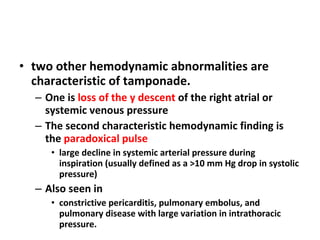

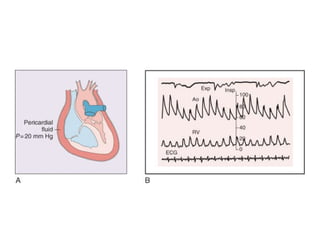

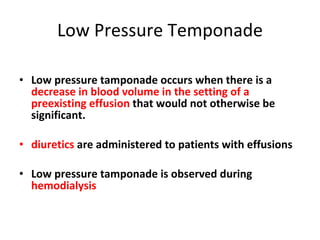

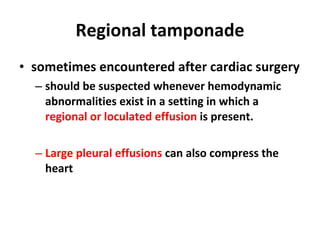

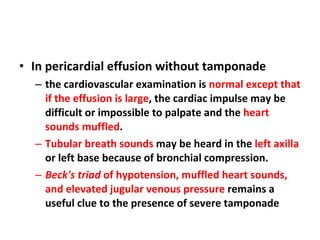

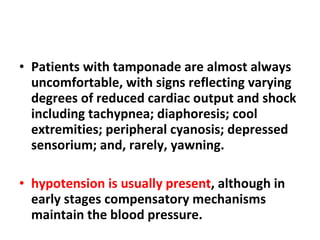

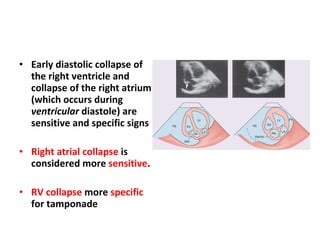

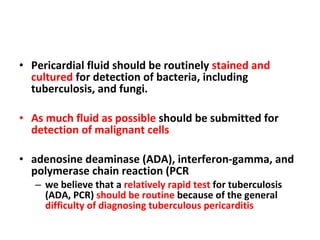

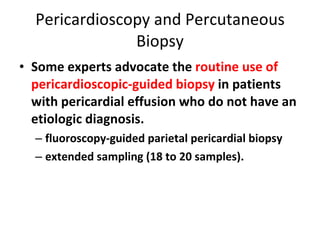

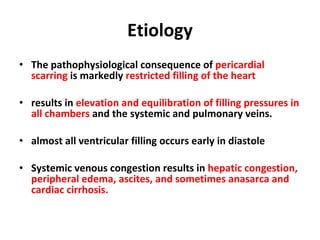

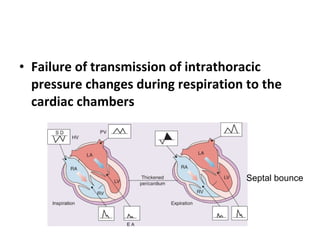

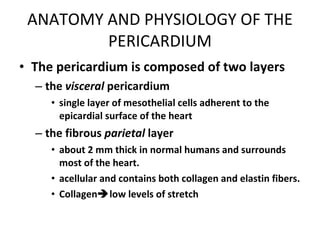

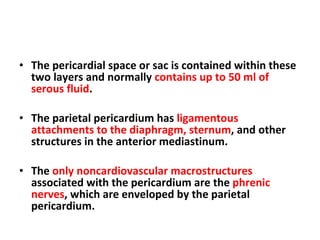

The document summarizes pericardial diseases. It discusses the anatomy and physiology of the pericardium, acute pericarditis including symptoms, diagnosis and treatment, and pericardial effusion and tamponade. Acute pericarditis is usually self-limited and treated with NSAIDs. Larger effusions may require hospitalization. Pericardial effusion can progress to tamponade, where fluid accumulation compresses the heart and impairs filling.

![Categories of Pericardial Disease and Selected Specific Etiologies Idiopathic Infectious Viral (echovirus, coxsackievirus, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, infectious mononucleosis, HIV/AIDs) Bacterial ( Pneumococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, mycoplasma, Lyme disease, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and others) Mycobacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare) Fungal (histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis) Protozoal Immune-inflammatory Connective tissue disease [*] (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, mixed) Arteritis (polyarteritis nodosa, temporal arteritis) Inflammatory bowel disease Early post–myocardial infarction Late post–myocardial infarction (Dressler syndrome), [*] late postcardiotomy/thoracotomy, [*] late posttrauma [*] Drug induced [*] (e.g., procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, cyclosporine) Neoplastic disease Primary: mesothelioma, fibrosarcoma, lipoma, and so on Secondary [*] : breast and lung carcinoma, lymphomas, Kaposi sarcoma](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pericardial-disease-1281967062-phpapp02/85/Pericardial-Disease-12-320.jpg)

![Categories of Pericardial Disease and Selected Specific Etiologies Radiation induced [*] Early postcardiac surgery Hemopericardium Trauma Post–myocardial infarction free wall rupture Device and procedure related: percutaneous coronary procedures, implantable defibrillators, pacemakers, post–arrhythmia ablation, post–atrial septal defect closure, post–valve repair/replacement Dissecting aortic aneurysm Trauma Blunt and penetrating, [*] post–cardiopulmonary resuscitation [*] Congenital Cysts, congenital absence Miscellaneous Cholesterol (“gold paint” pericarditis) Chronic renal failure, dialysis related Chylopericardium Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism Amyloidosis Aortic dissection](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pericardial-disease-1281967062-phpapp02/85/Pericardial-Disease-13-320.jpg)