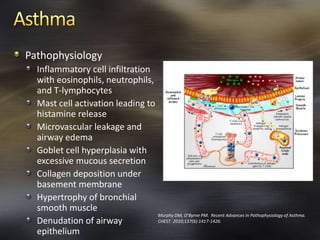

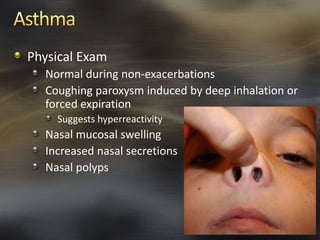

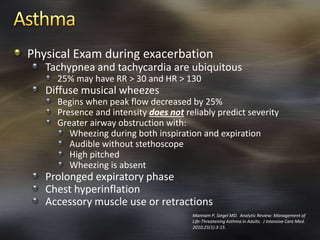

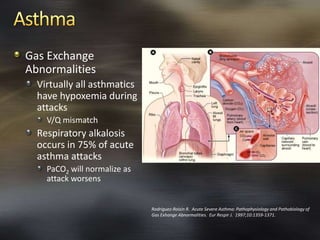

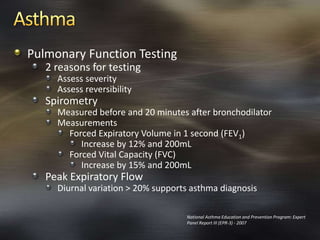

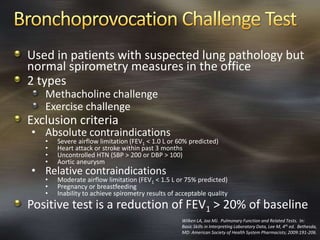

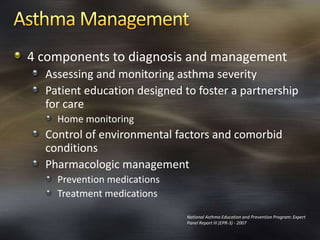

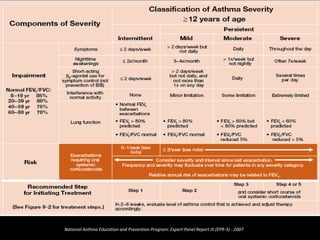

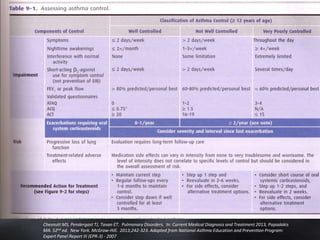

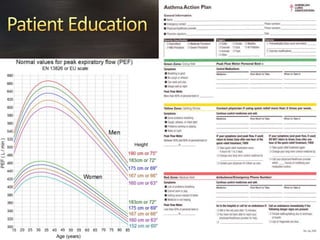

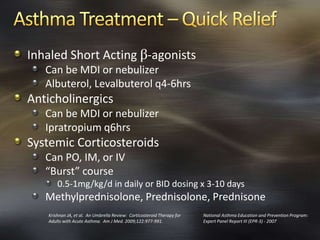

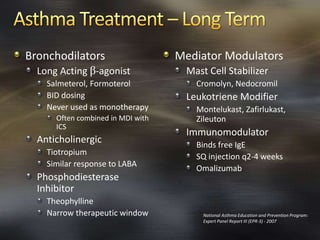

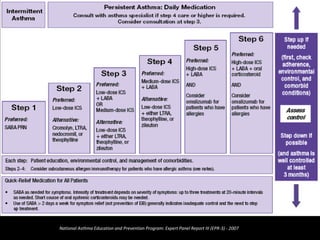

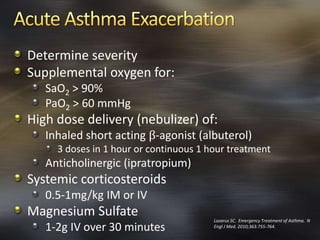

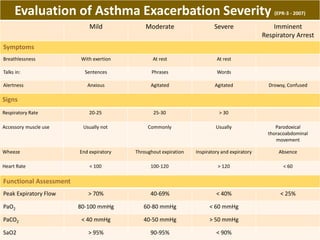

Kristopher R. Maday is an assistant professor and academic coordinator of the surgical physician assistant program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The document discusses asthma, including its pathophysiology, risk factors, diagnosis, management, and treatment. It provides detailed information on evaluating and diagnosing the severity of asthma exacerbations. The goals of asthma therapy and examples of common medications used to treat and prevent asthma are also summarized.