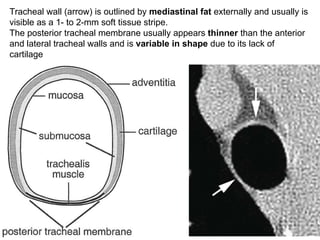

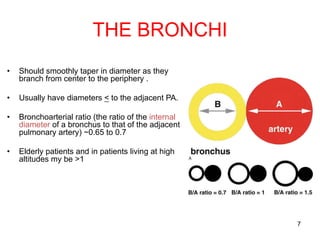

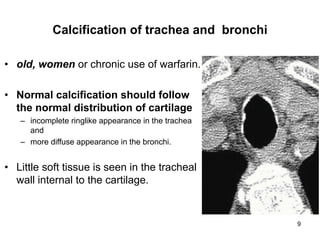

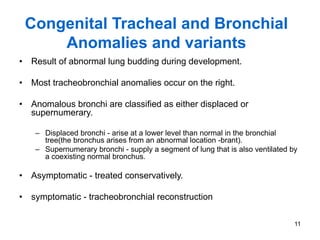

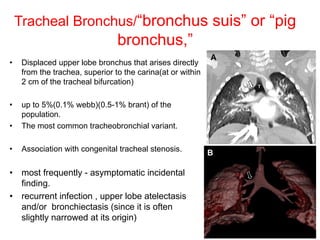

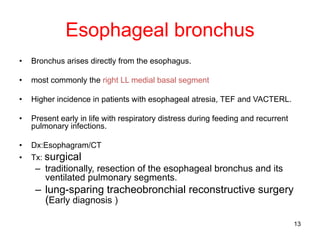

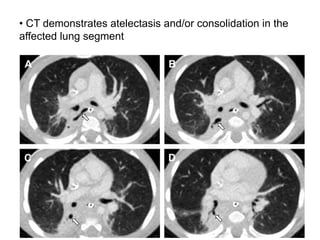

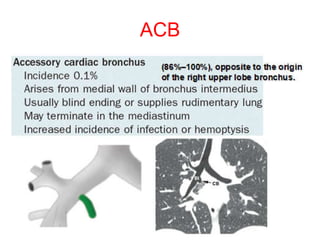

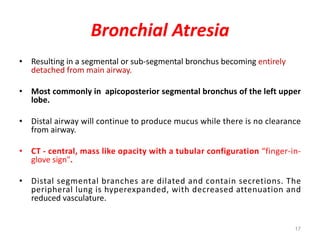

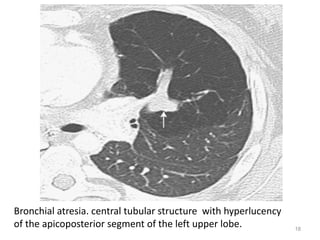

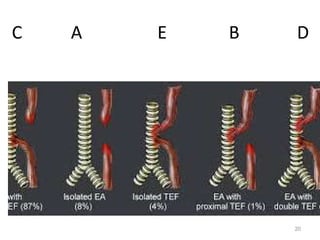

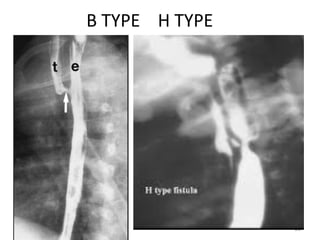

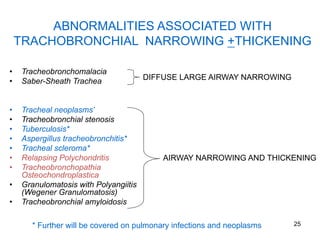

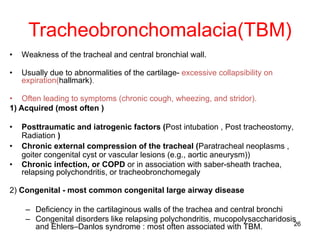

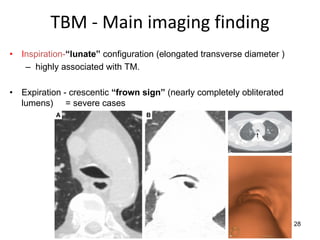

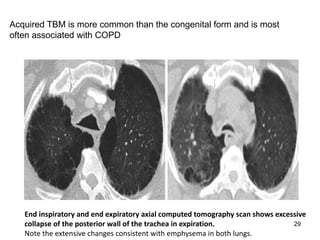

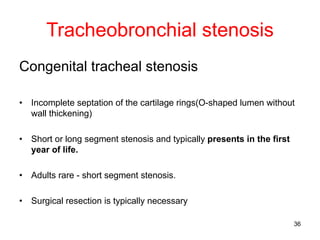

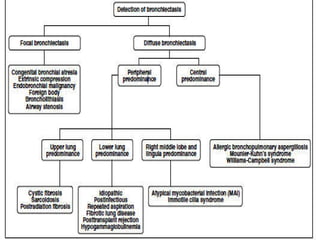

This document provides an outline and overview of airway diseases. It begins with an introduction to imaging of the airways and then covers various congenital anomalies and abnormalities that can cause tracheal and bronchial narrowing or dilation. Specific conditions discussed include tracheobronchomalacia, tracheal stenosis, bronchial atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, and esophageal bronchus. The functions of the large airways and common sites of calcification are also reviewed.