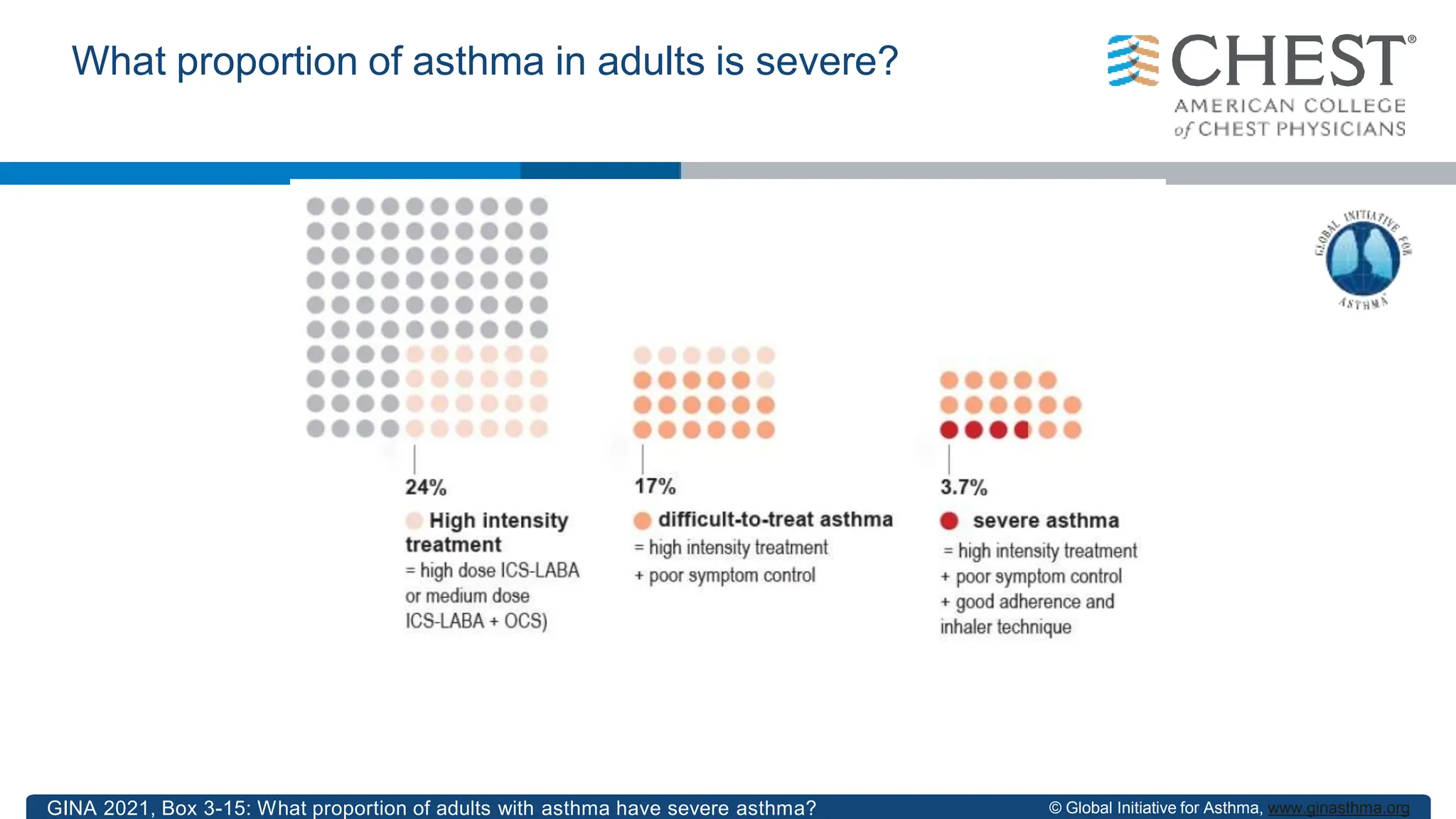

This document discusses asthma, including:

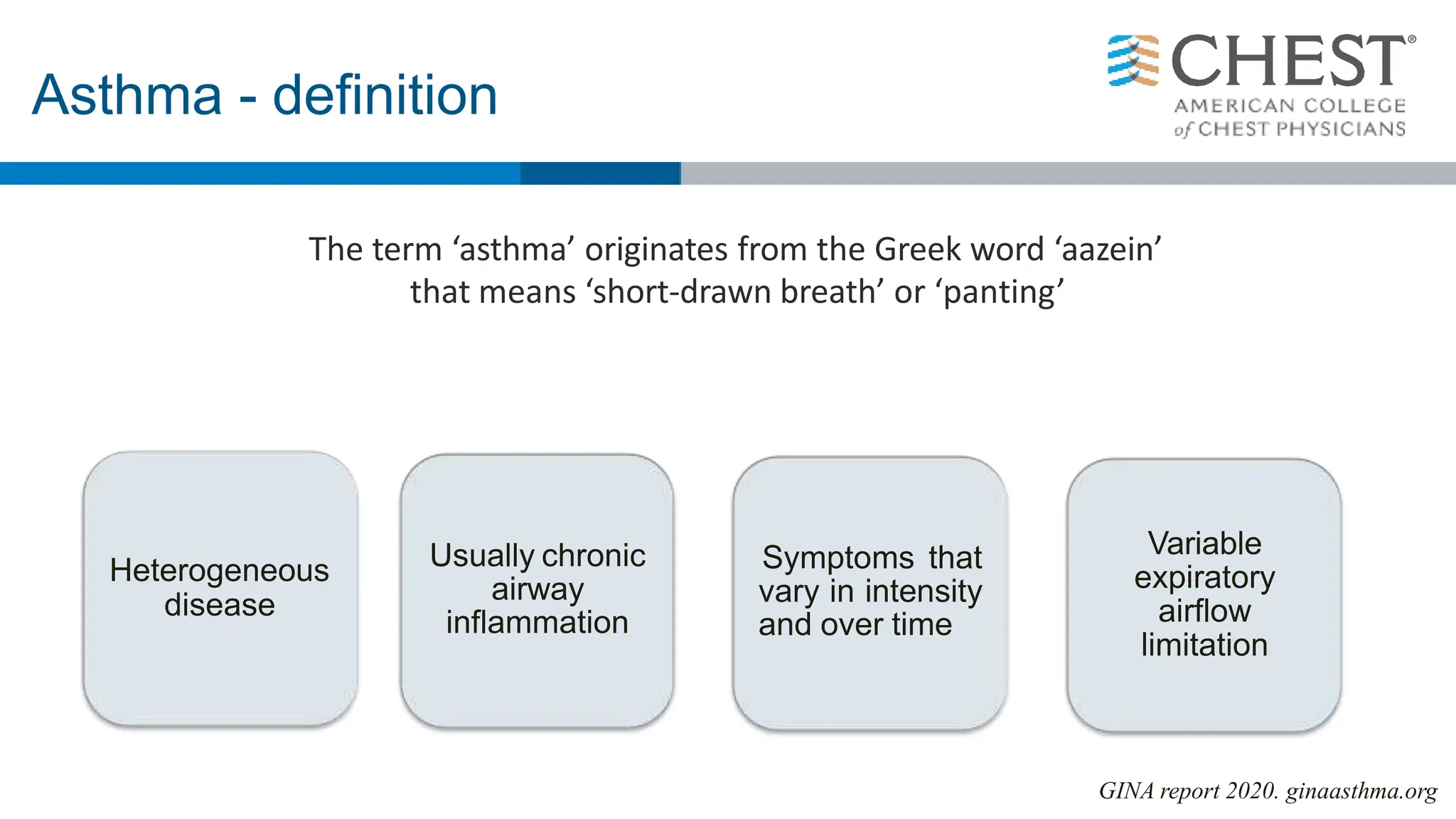

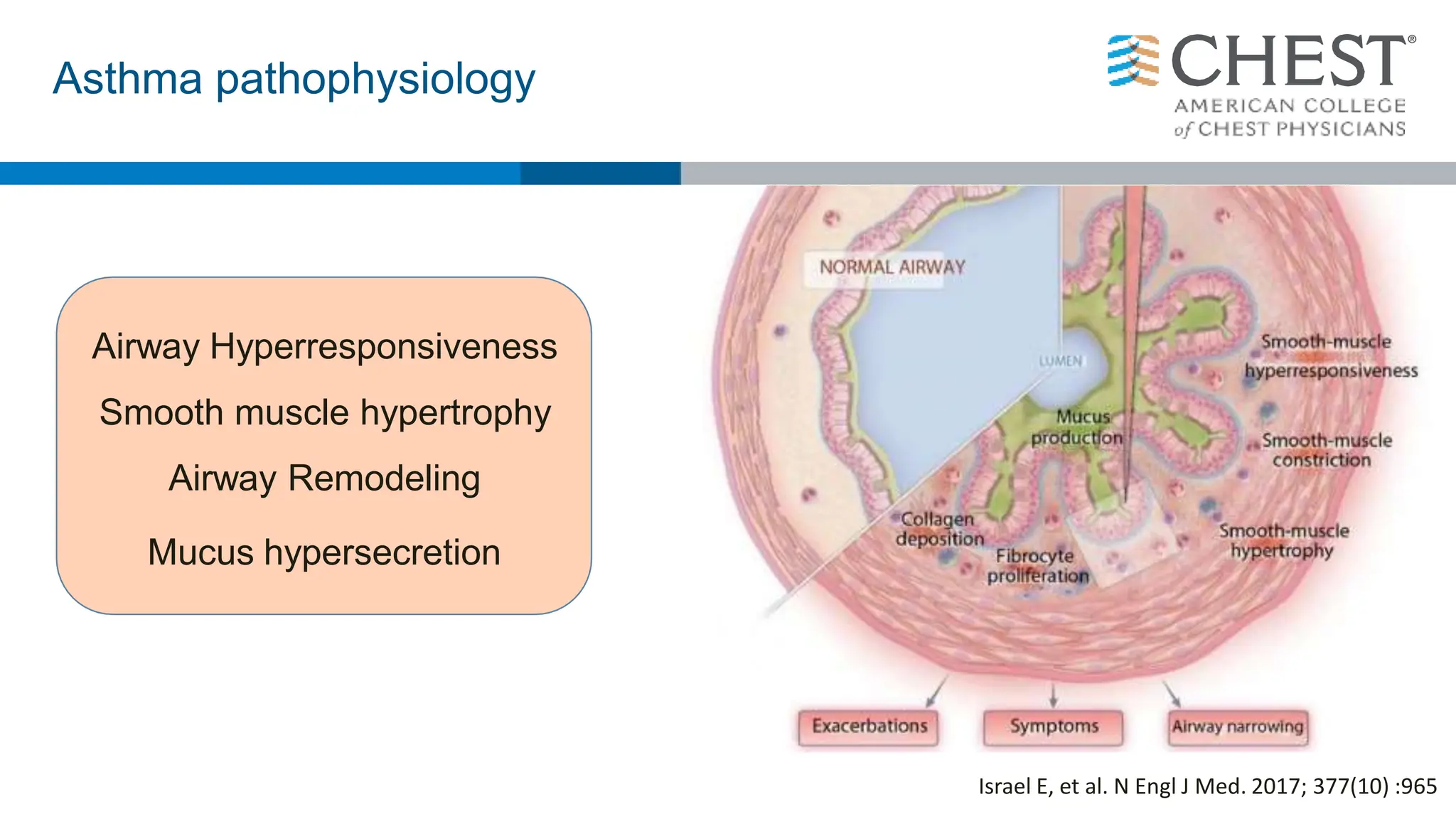

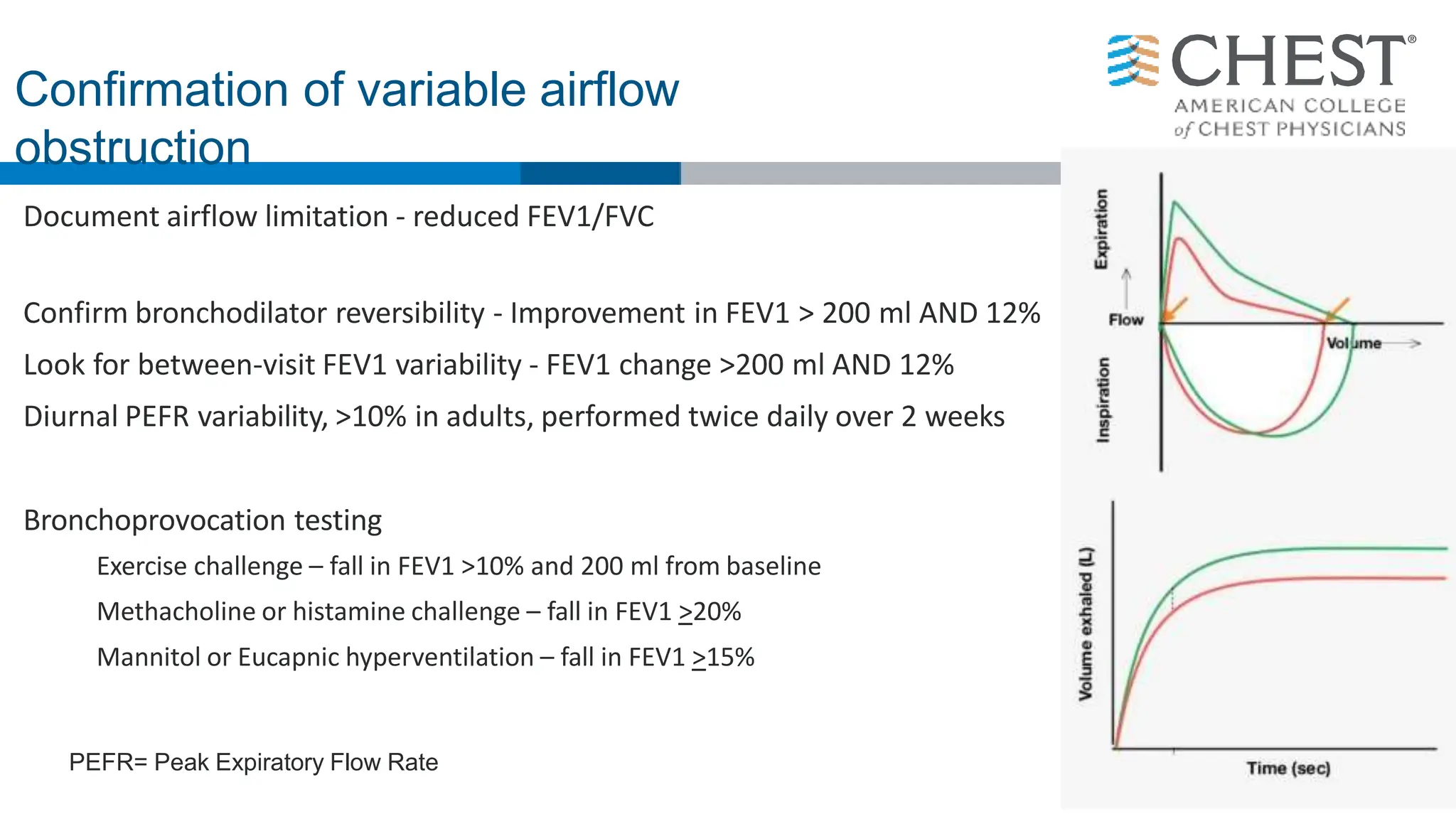

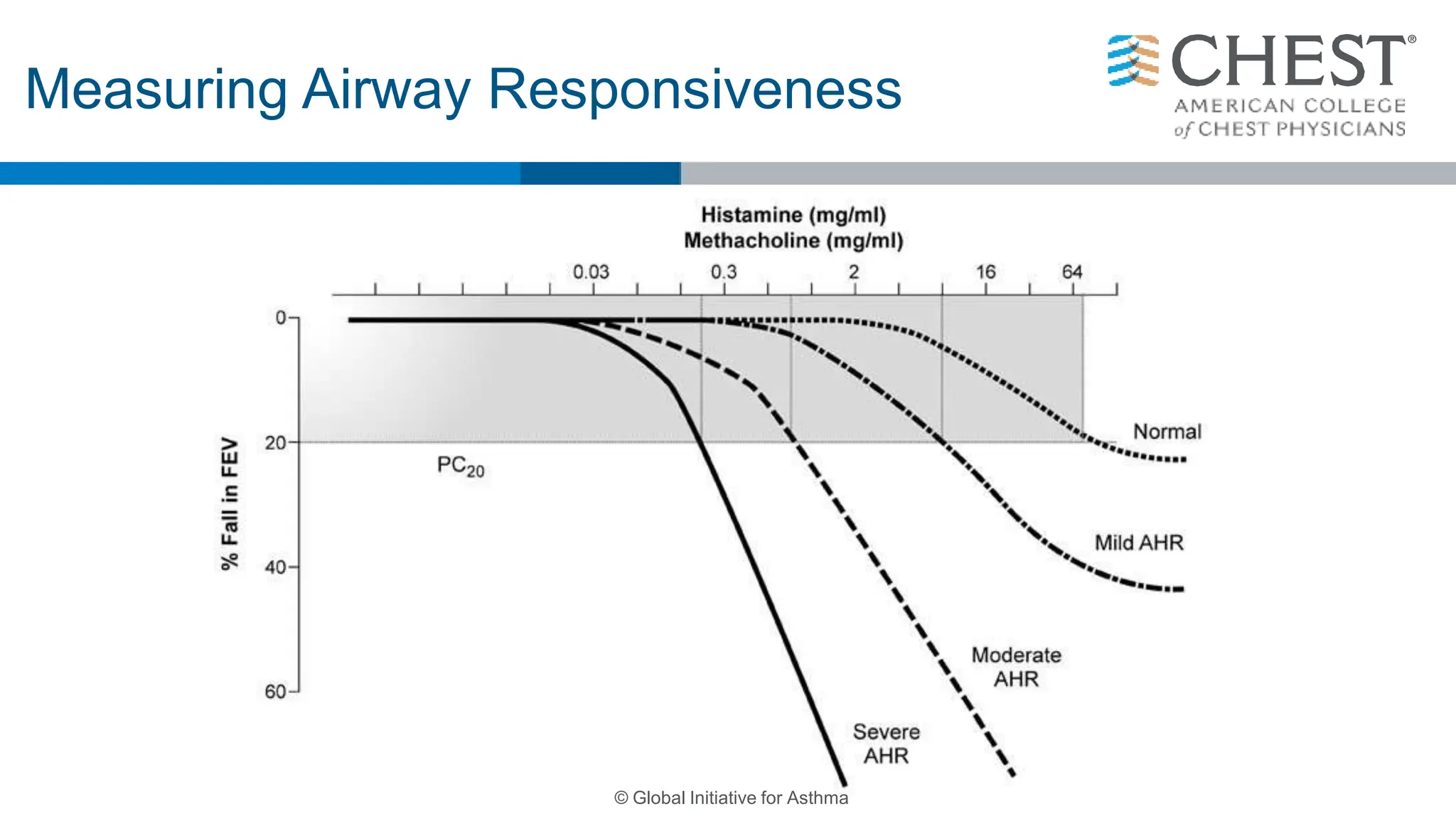

- The definition of asthma as a chronic airway disease characterized by variable airflow obstruction and airway hyperresponsiveness.

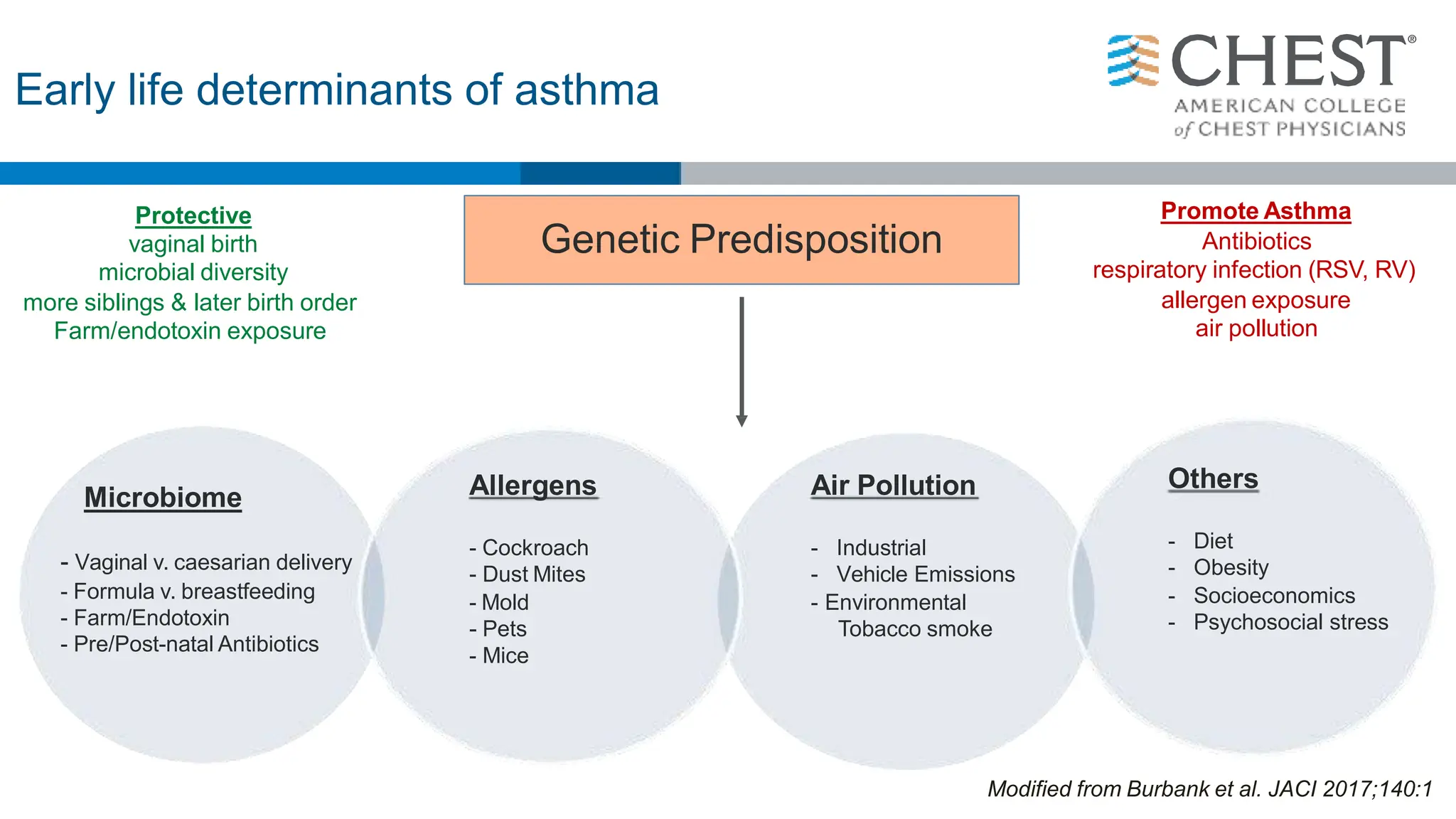

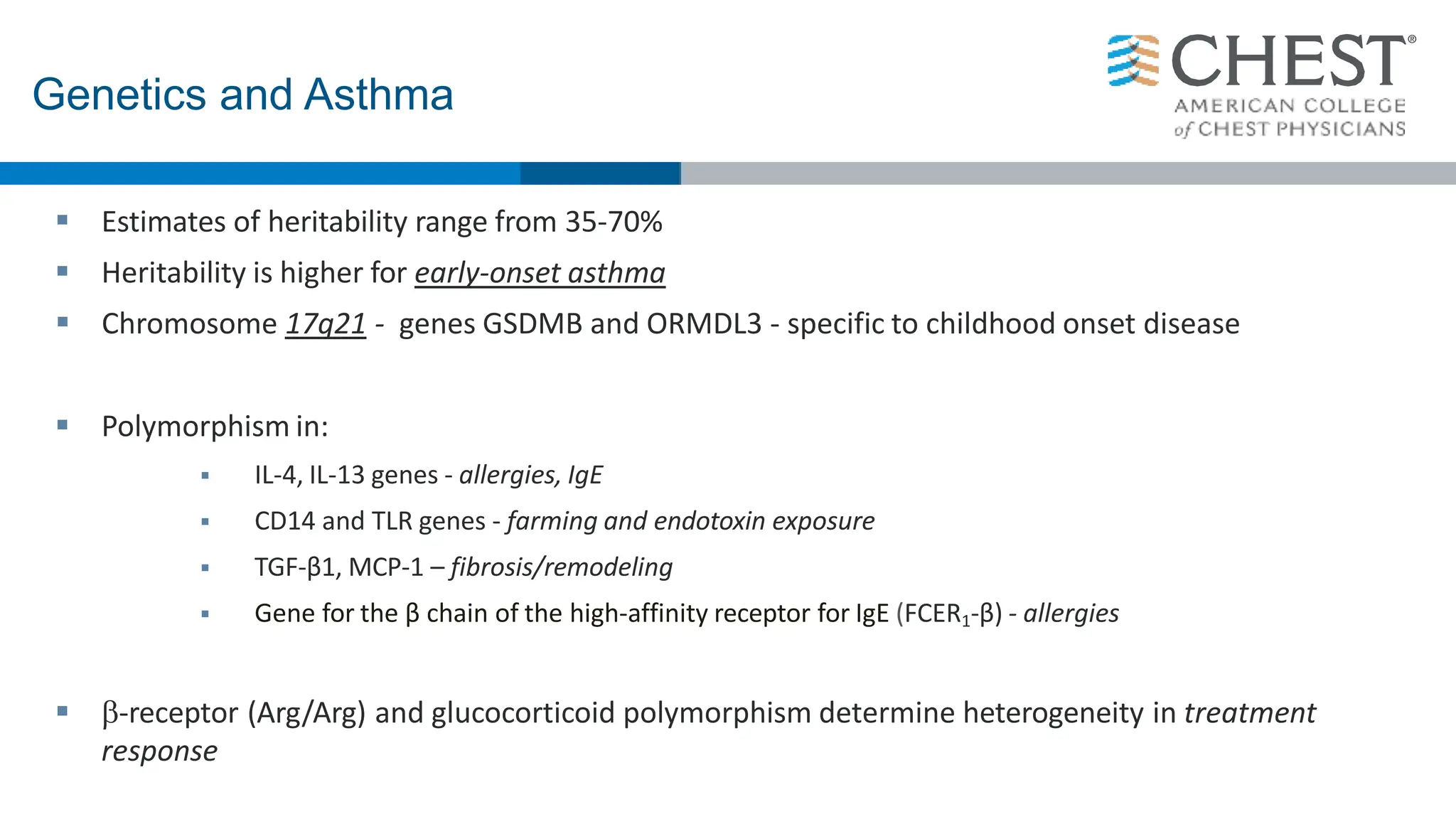

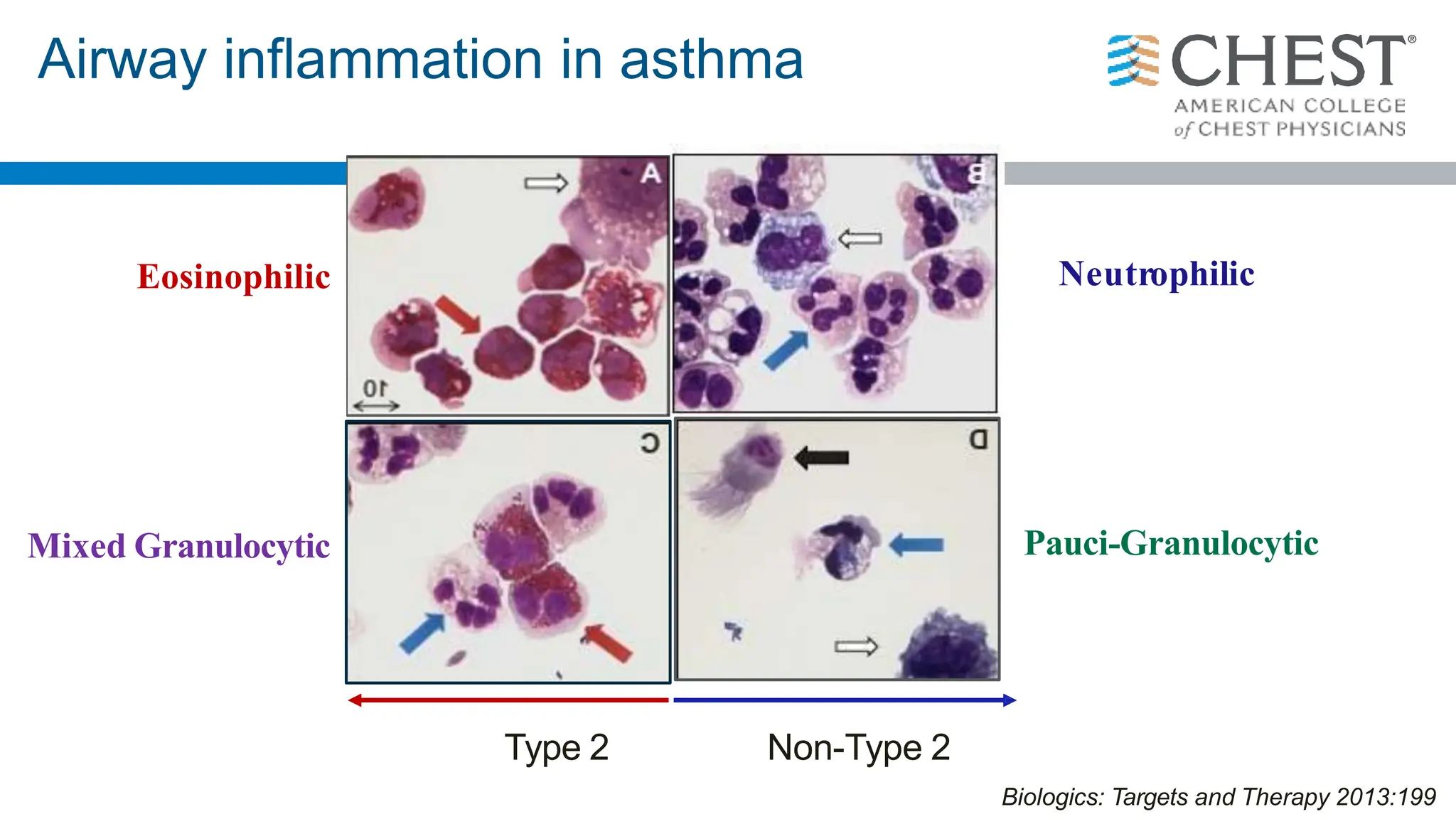

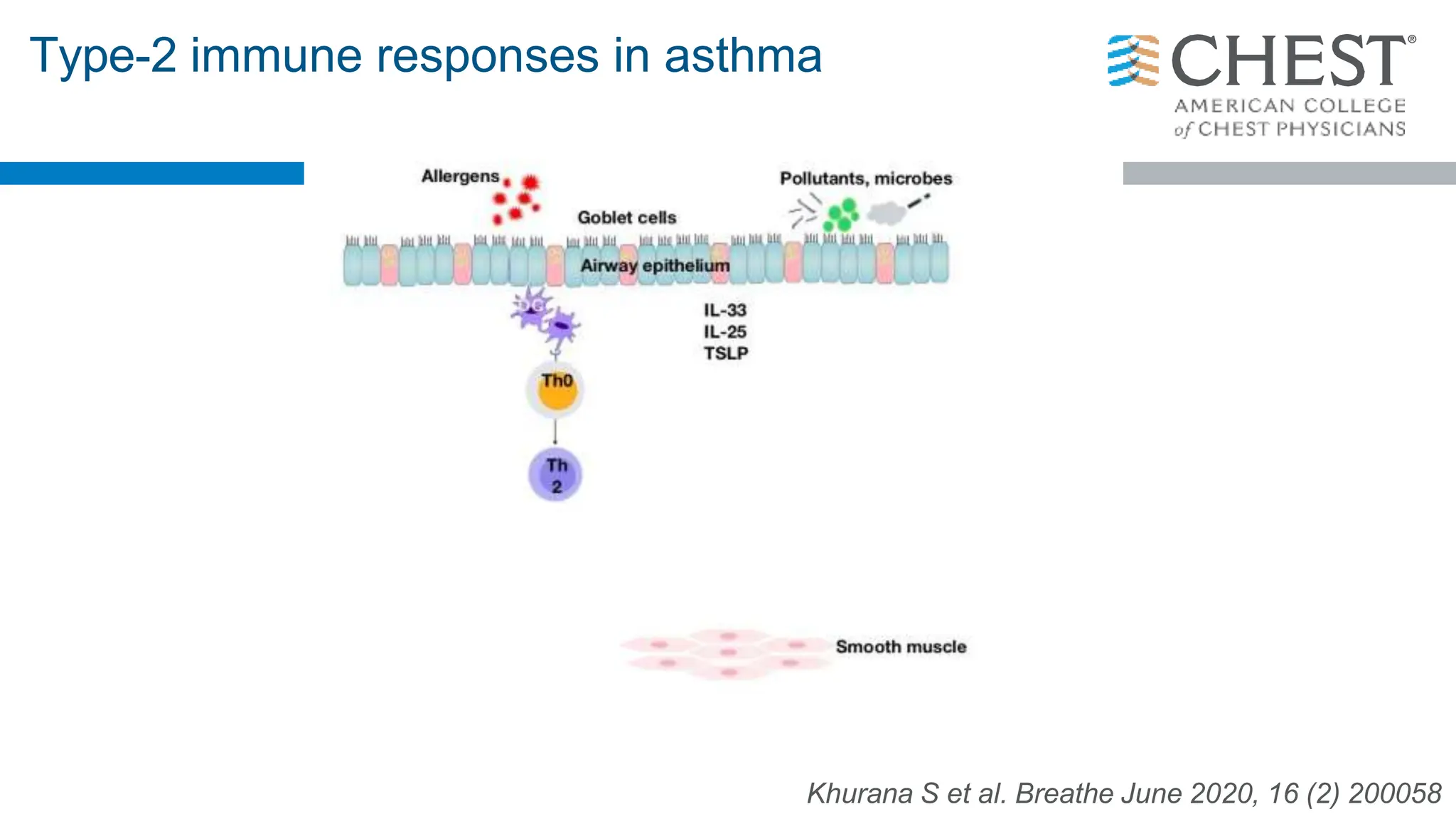

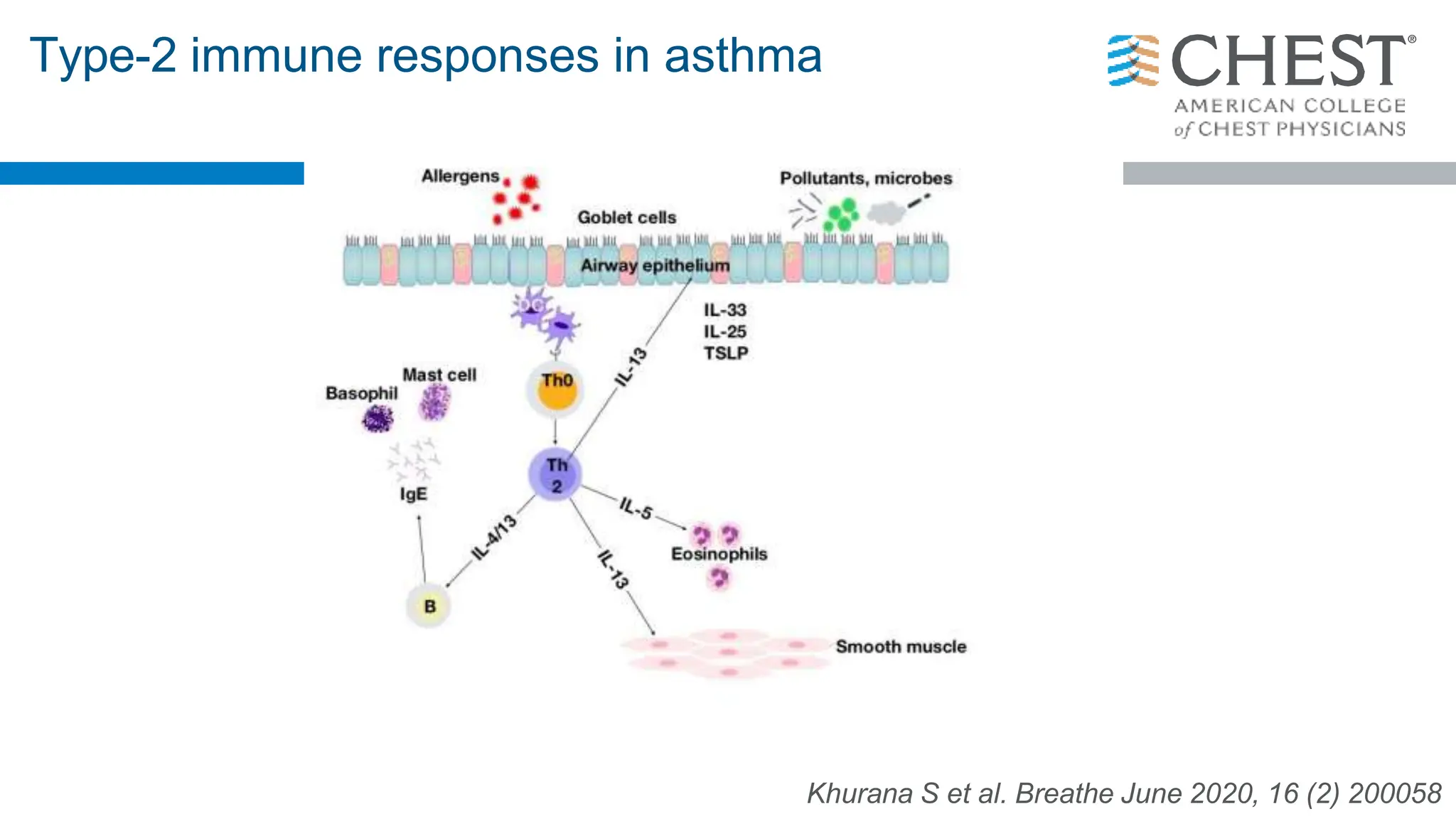

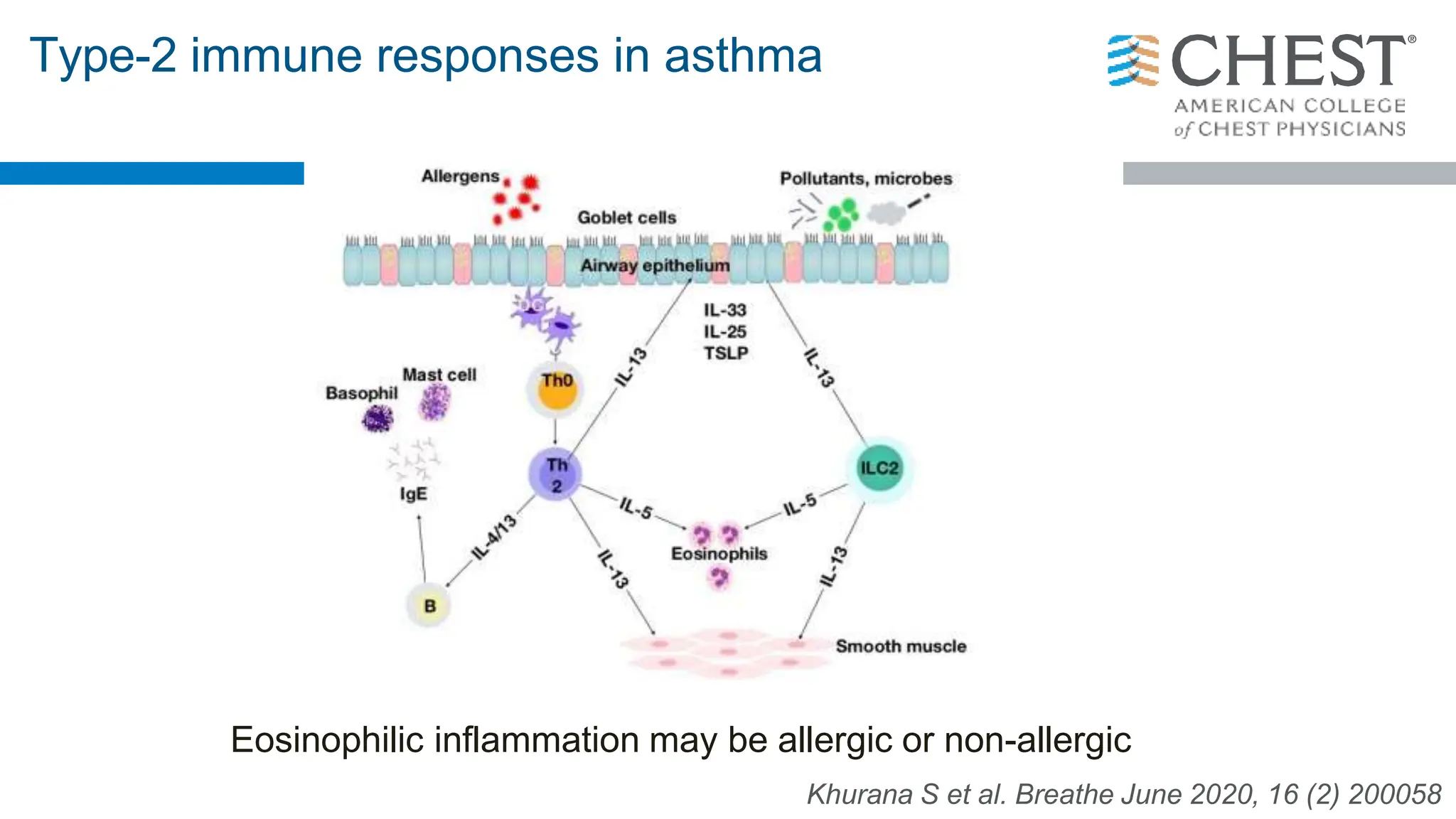

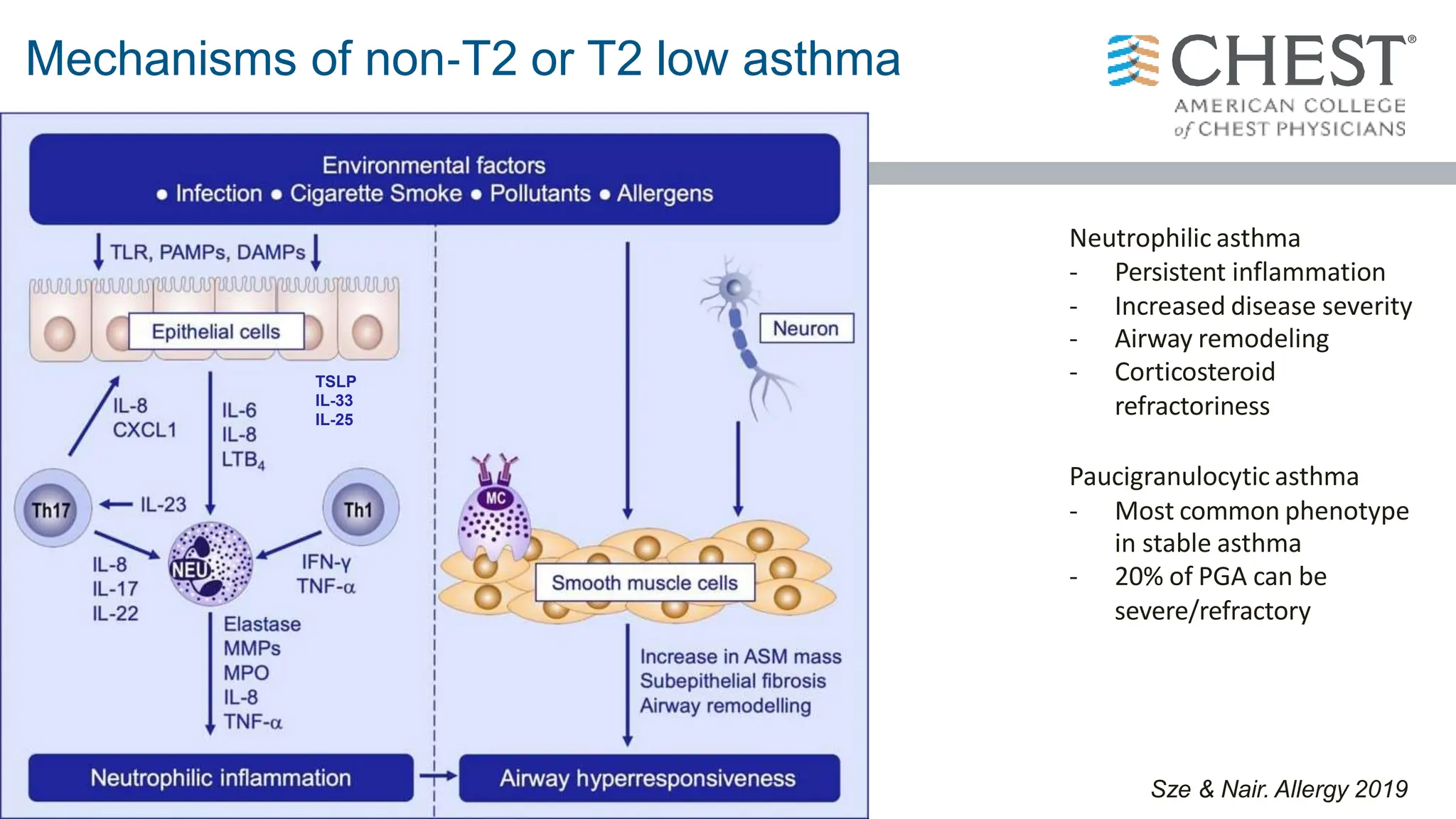

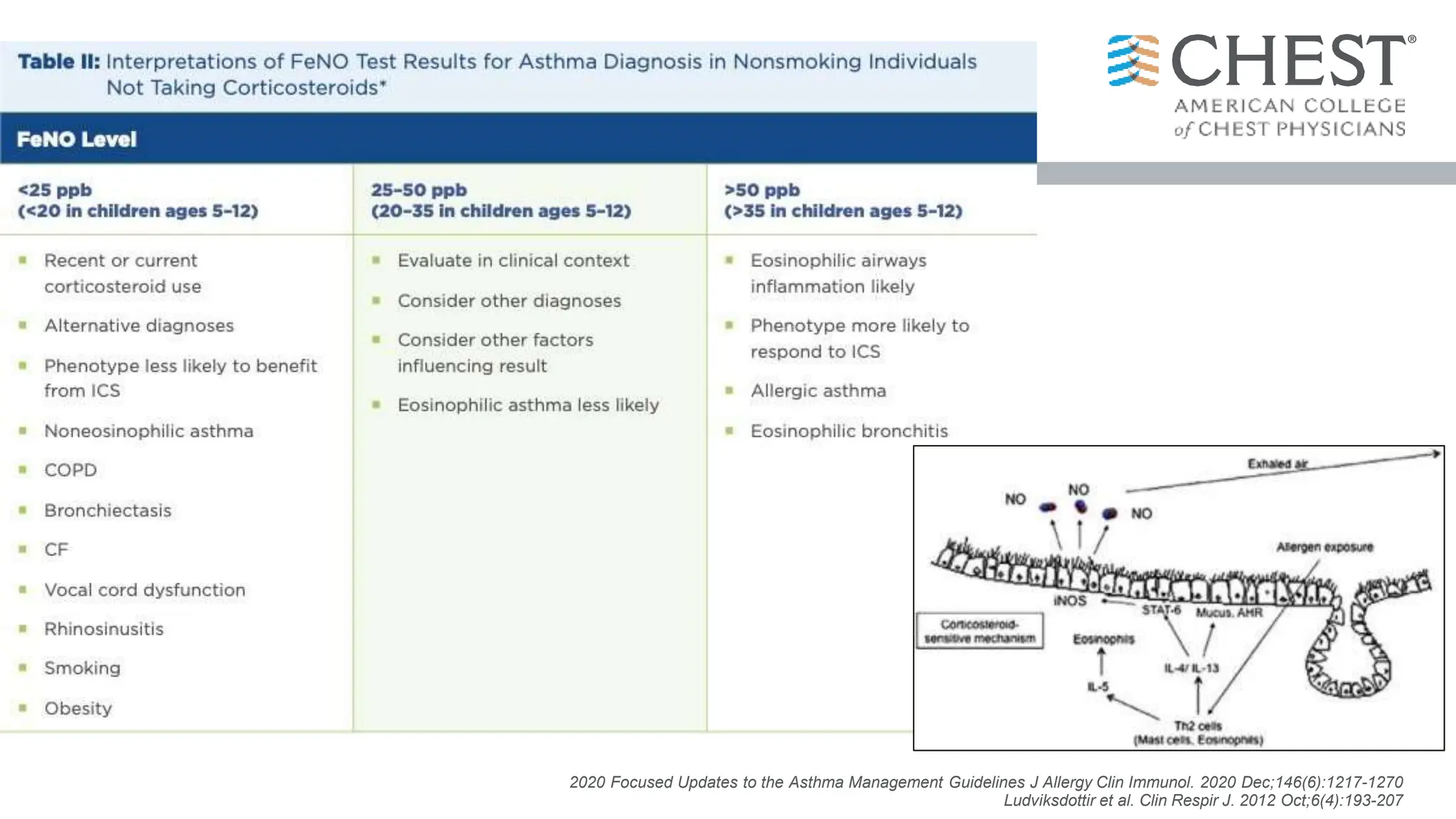

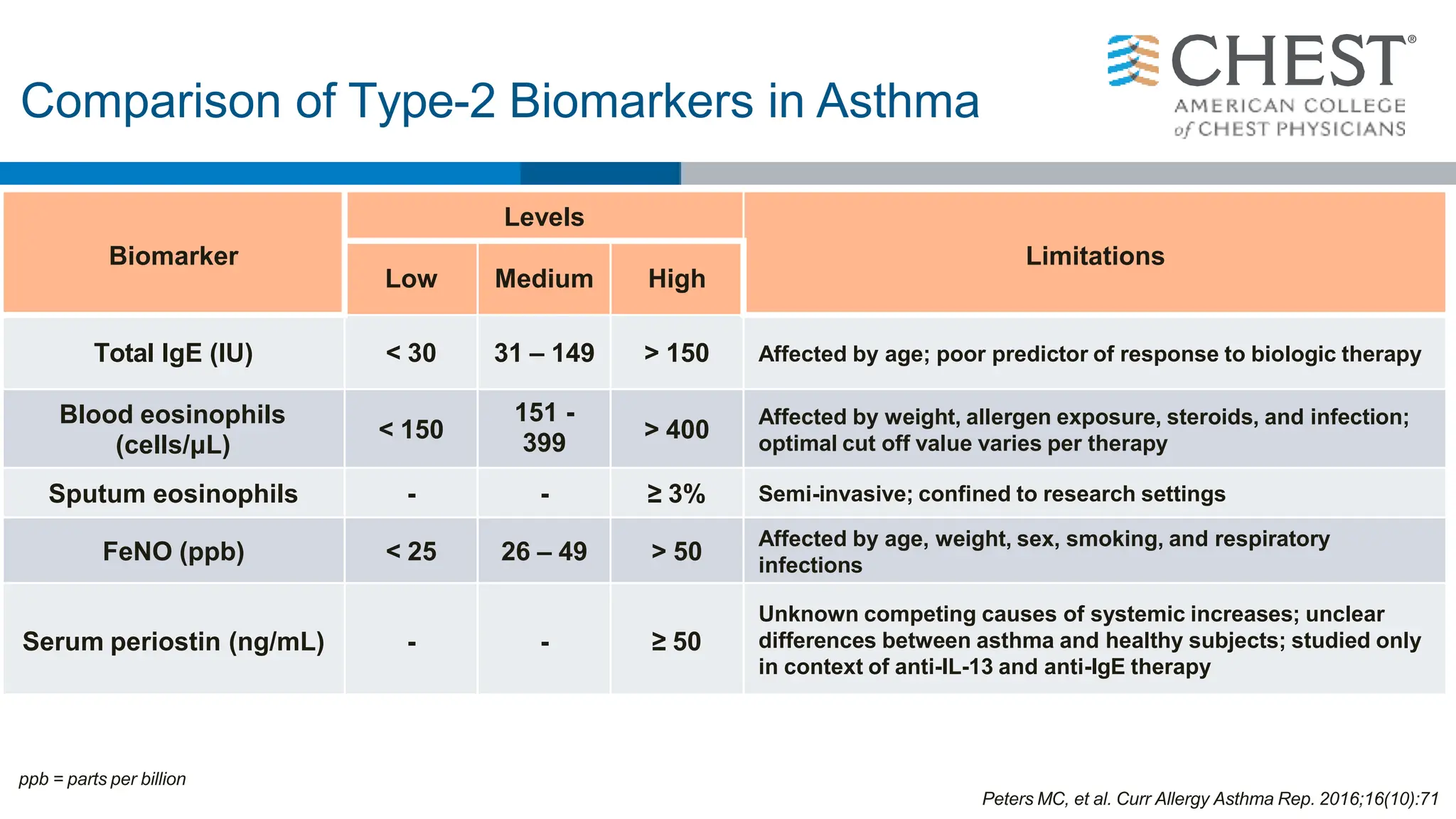

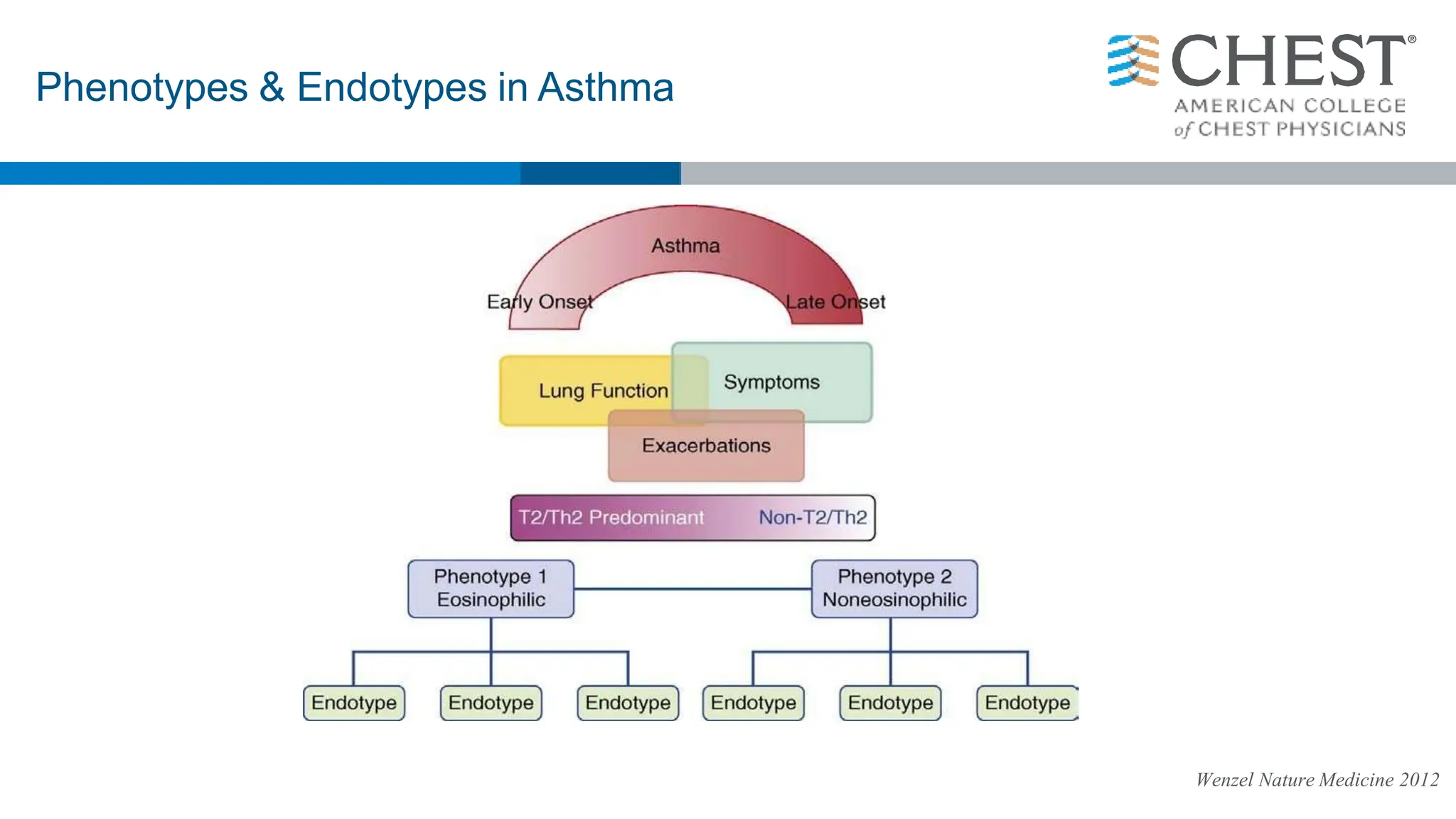

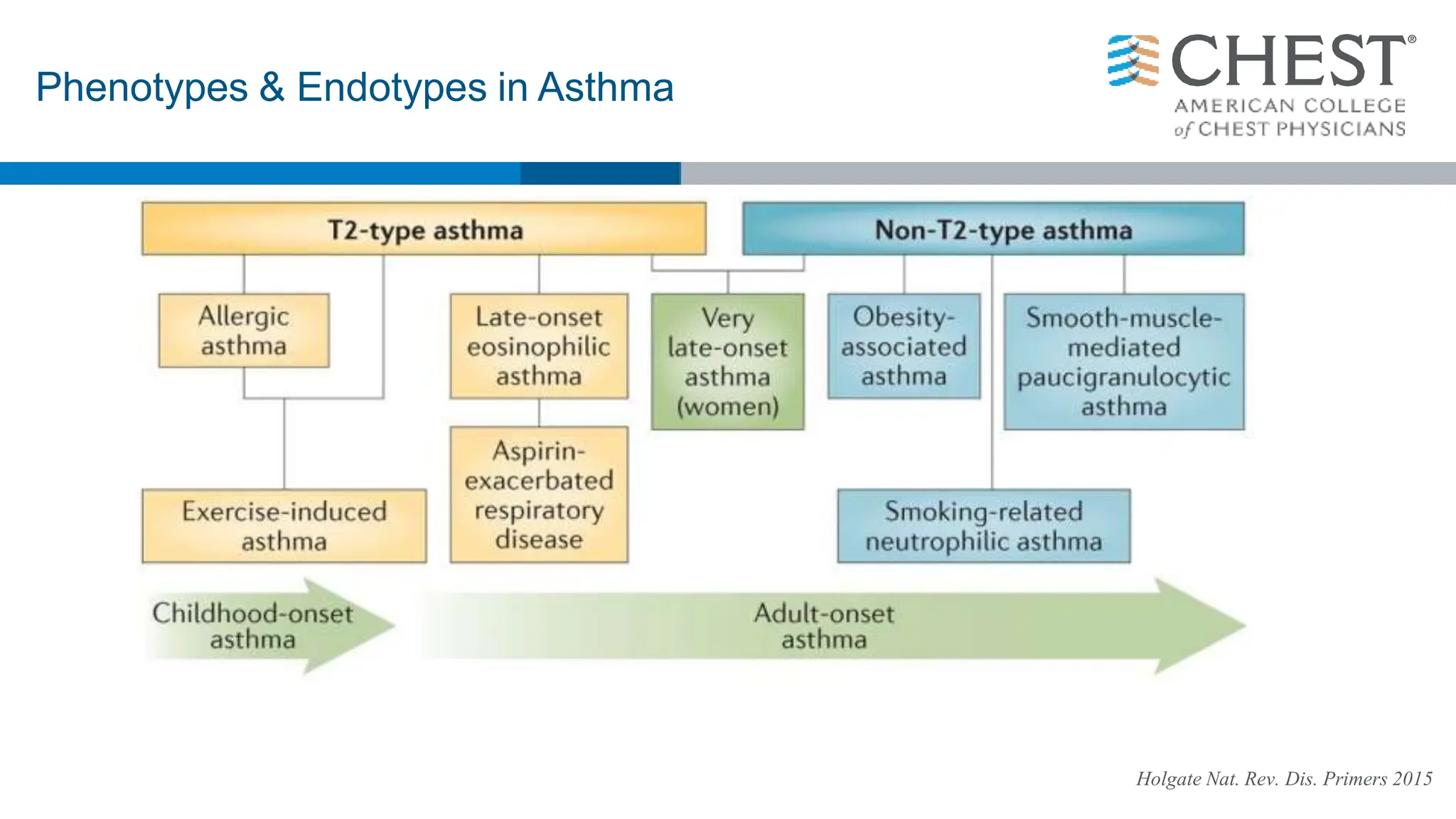

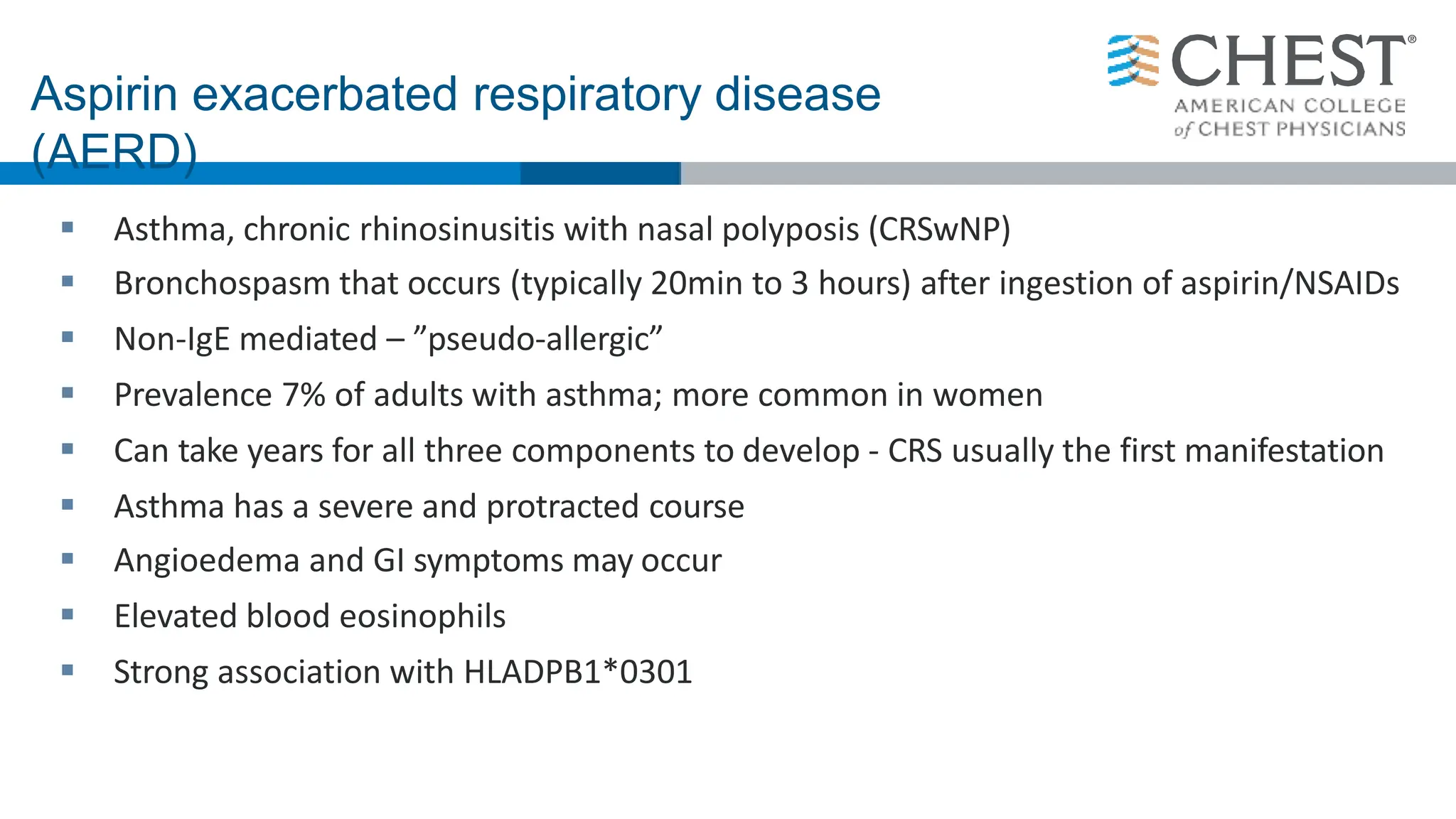

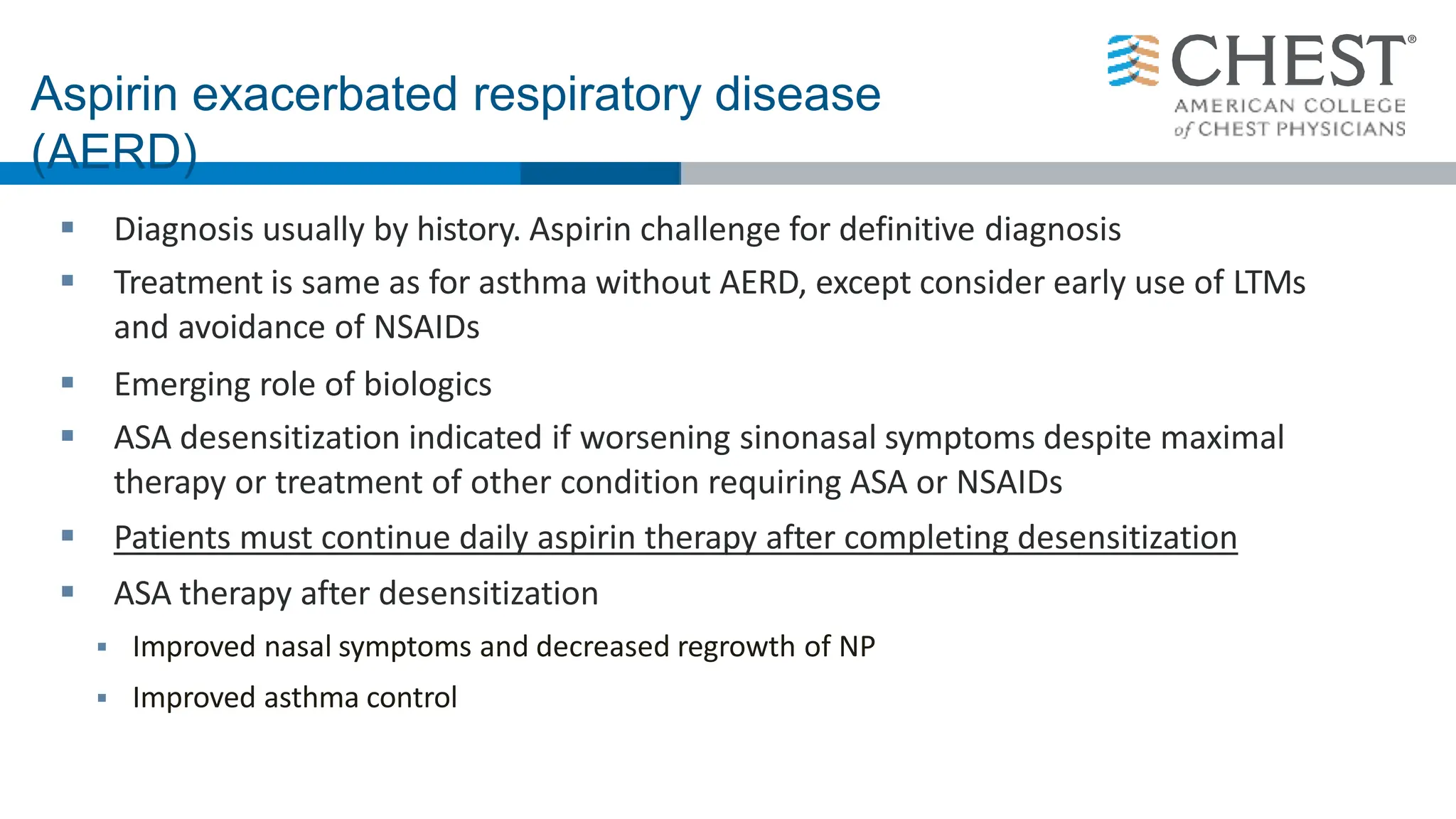

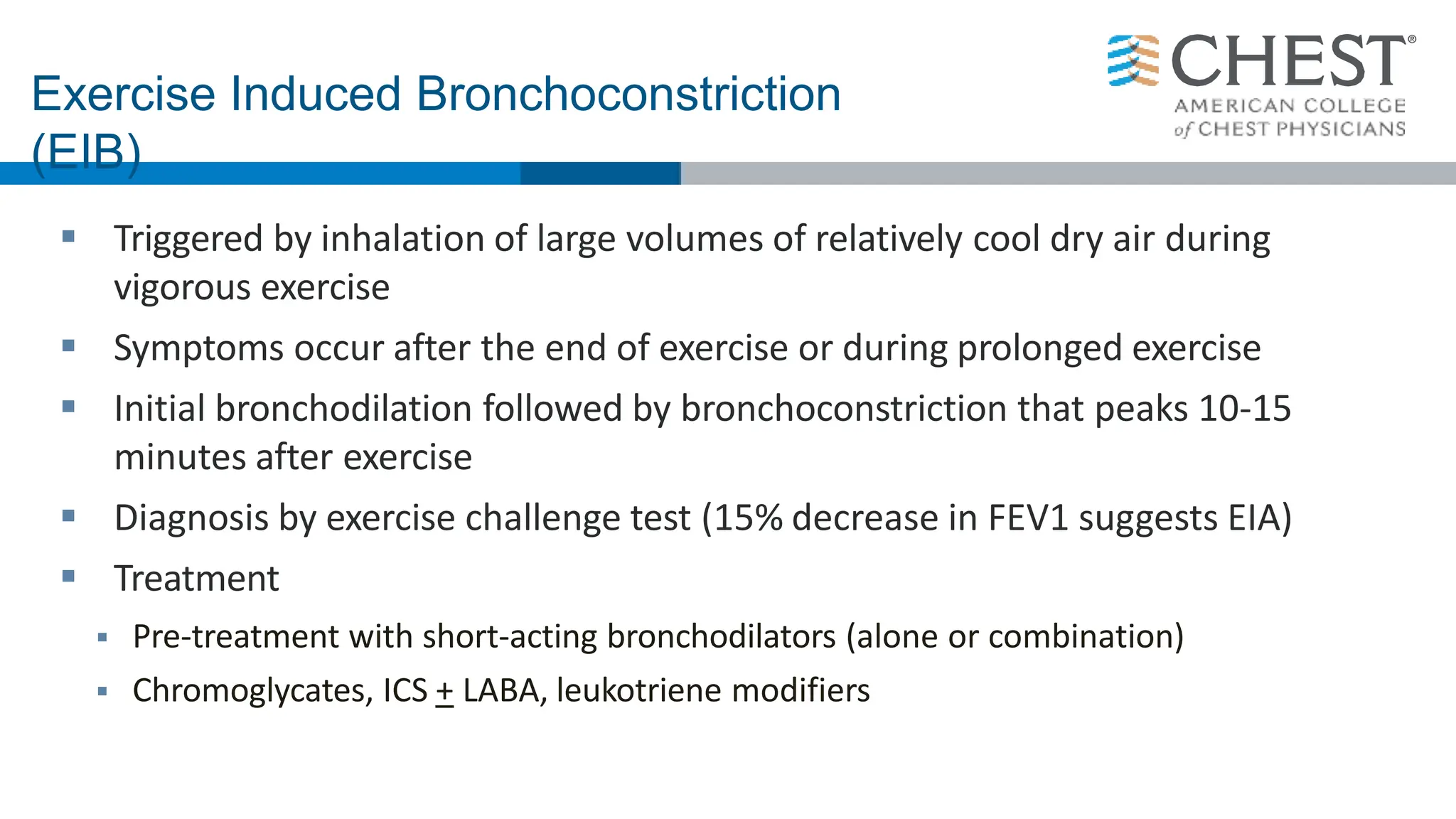

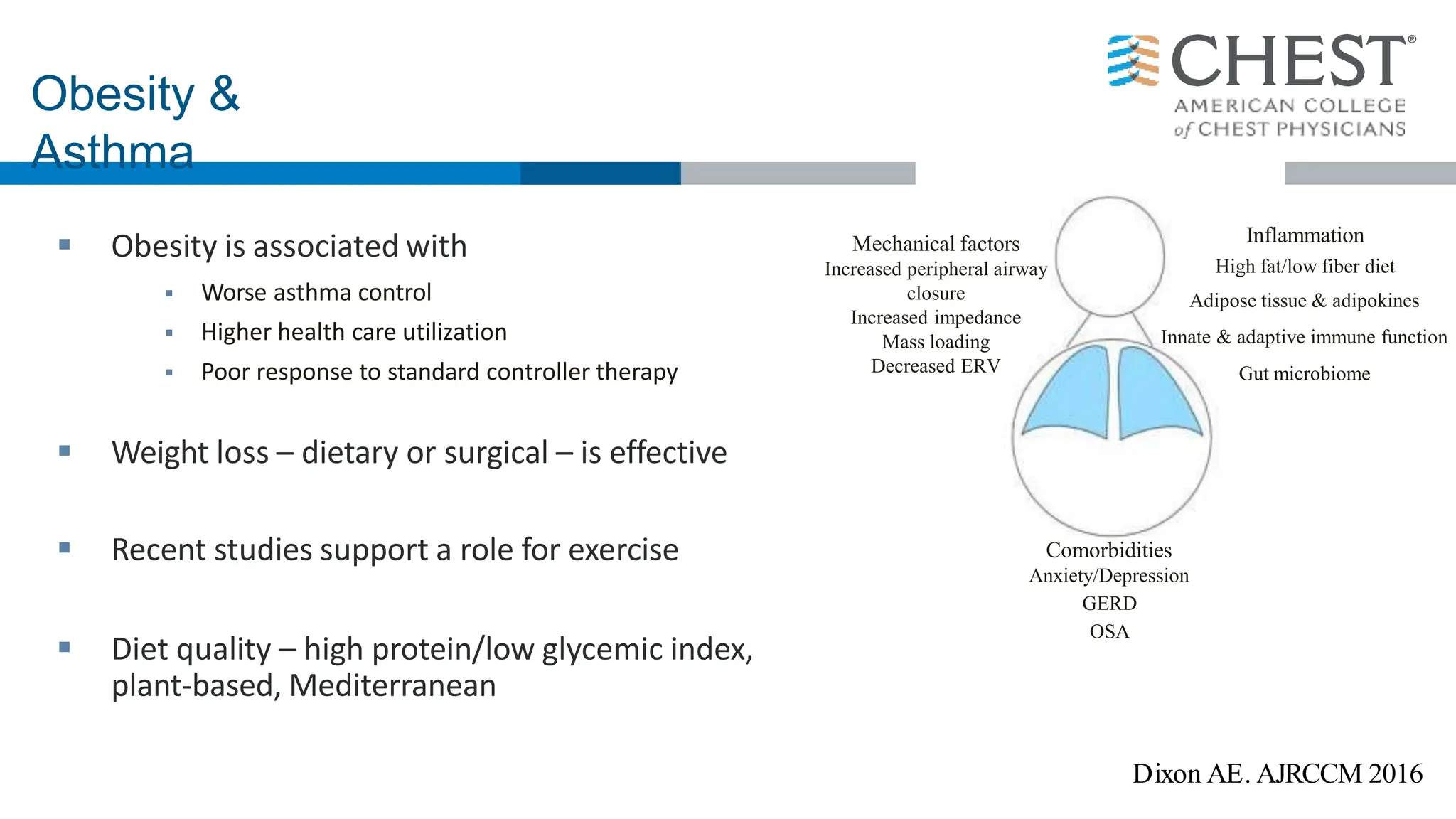

- Asthma is a heterogeneous disease influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, and has a complex pathophysiology involving airway inflammation.

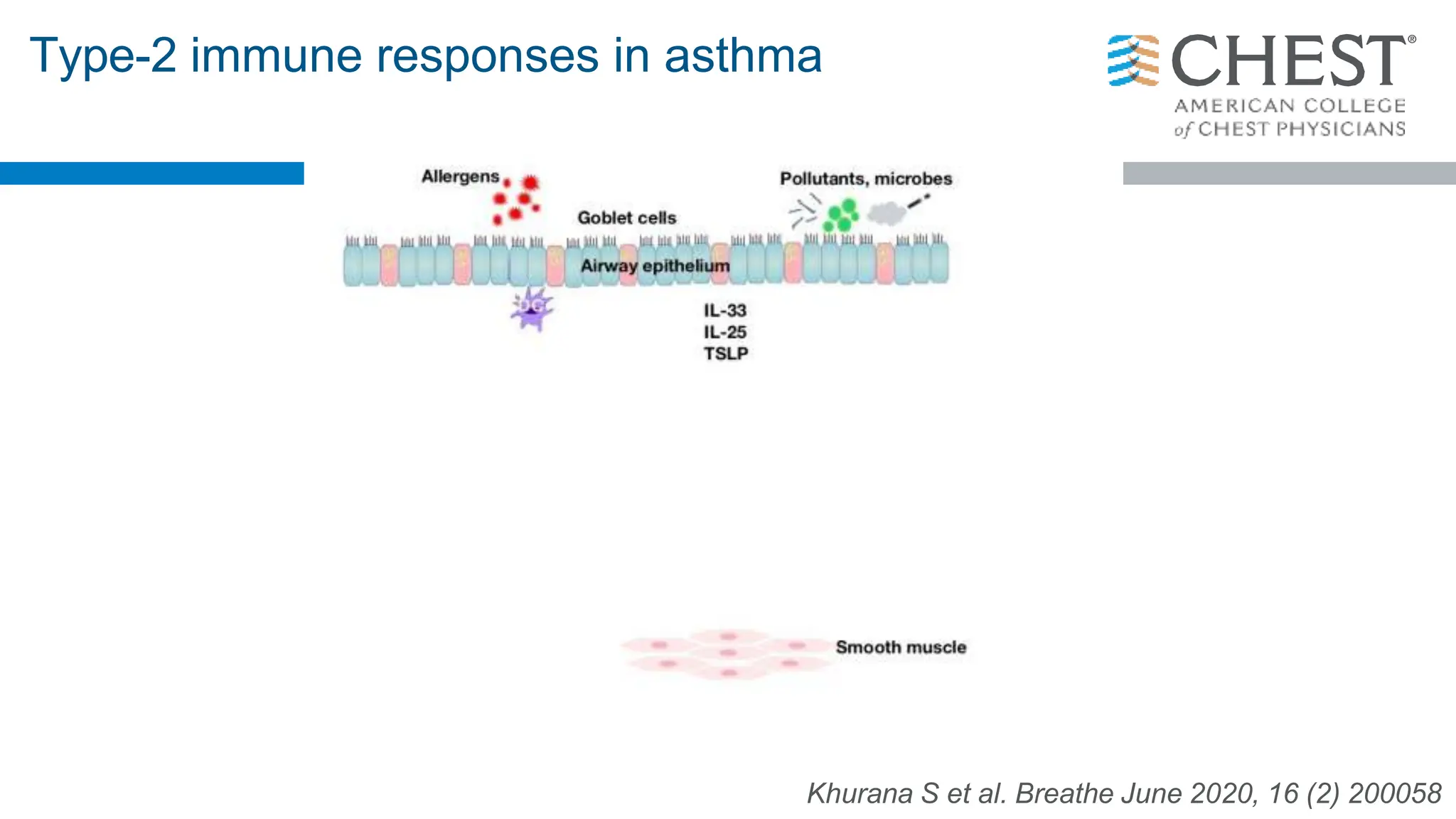

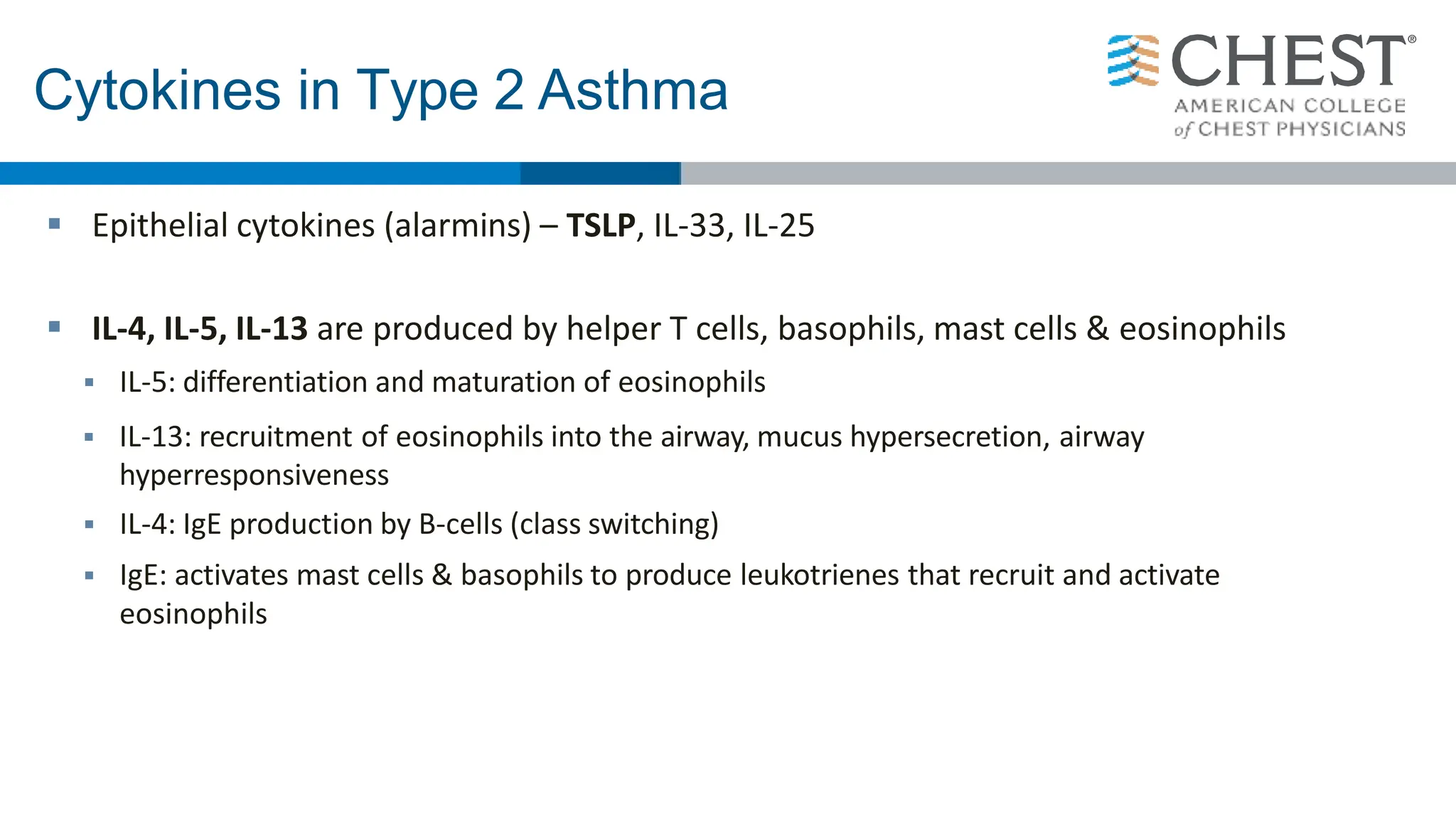

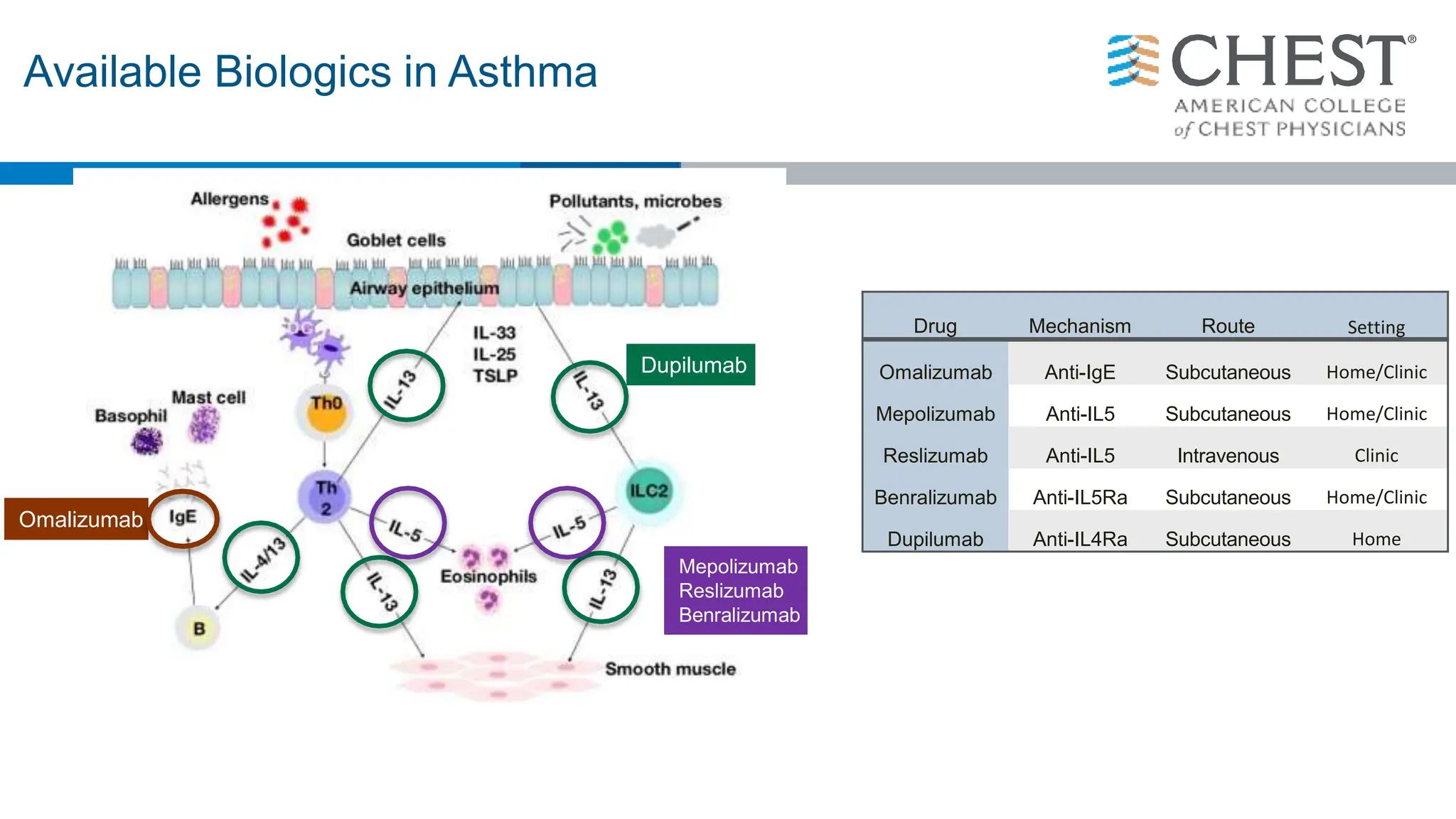

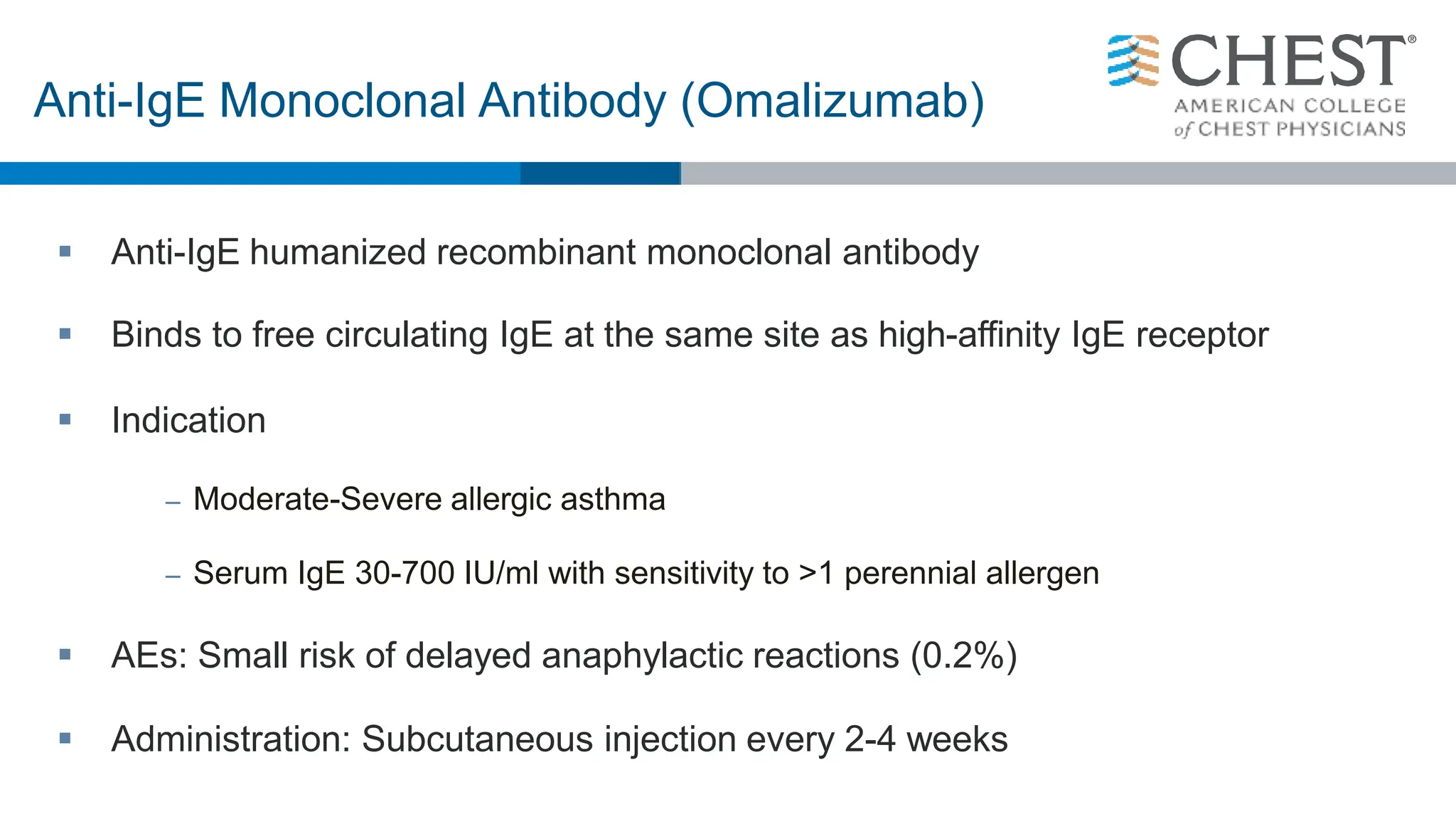

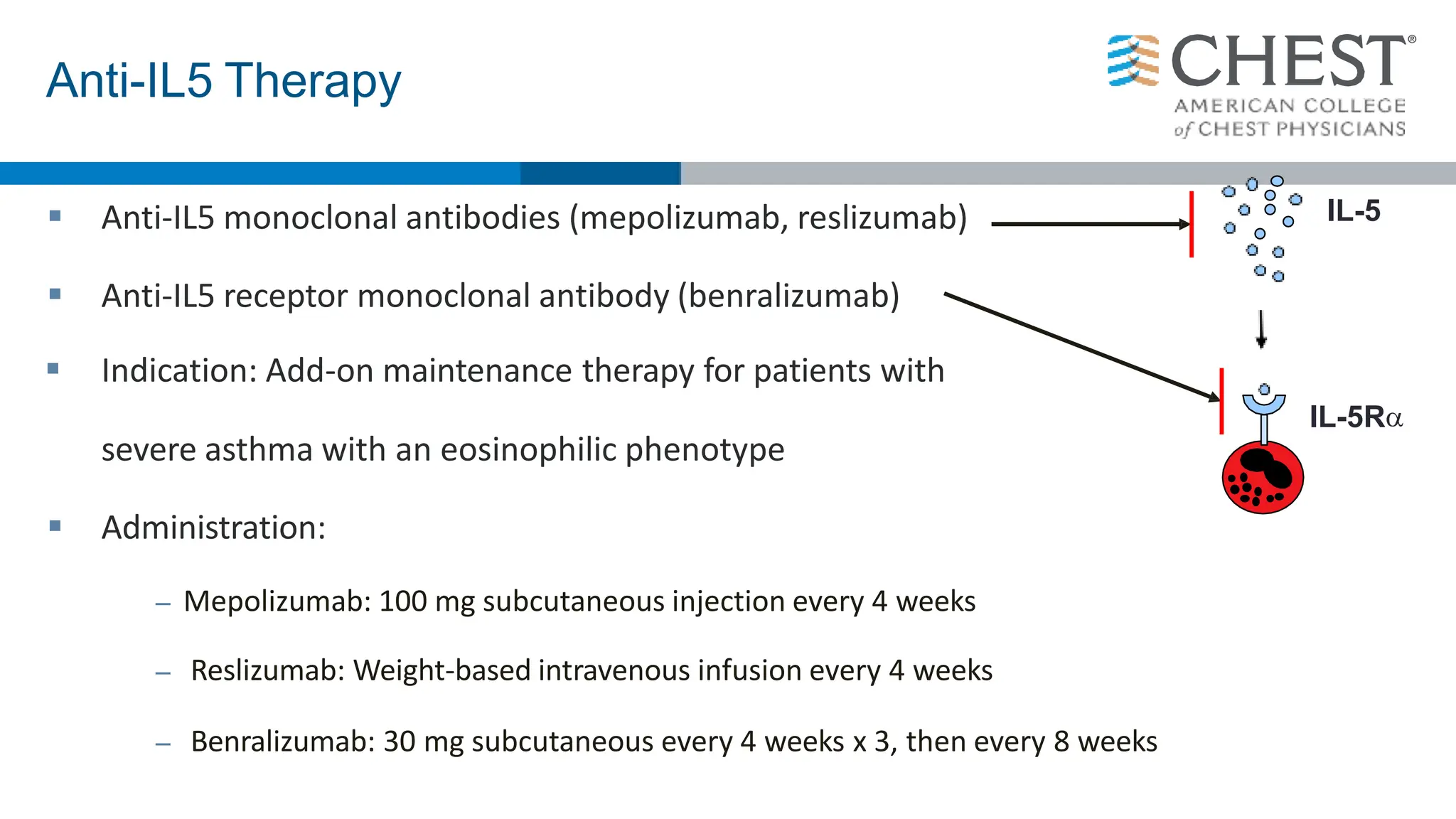

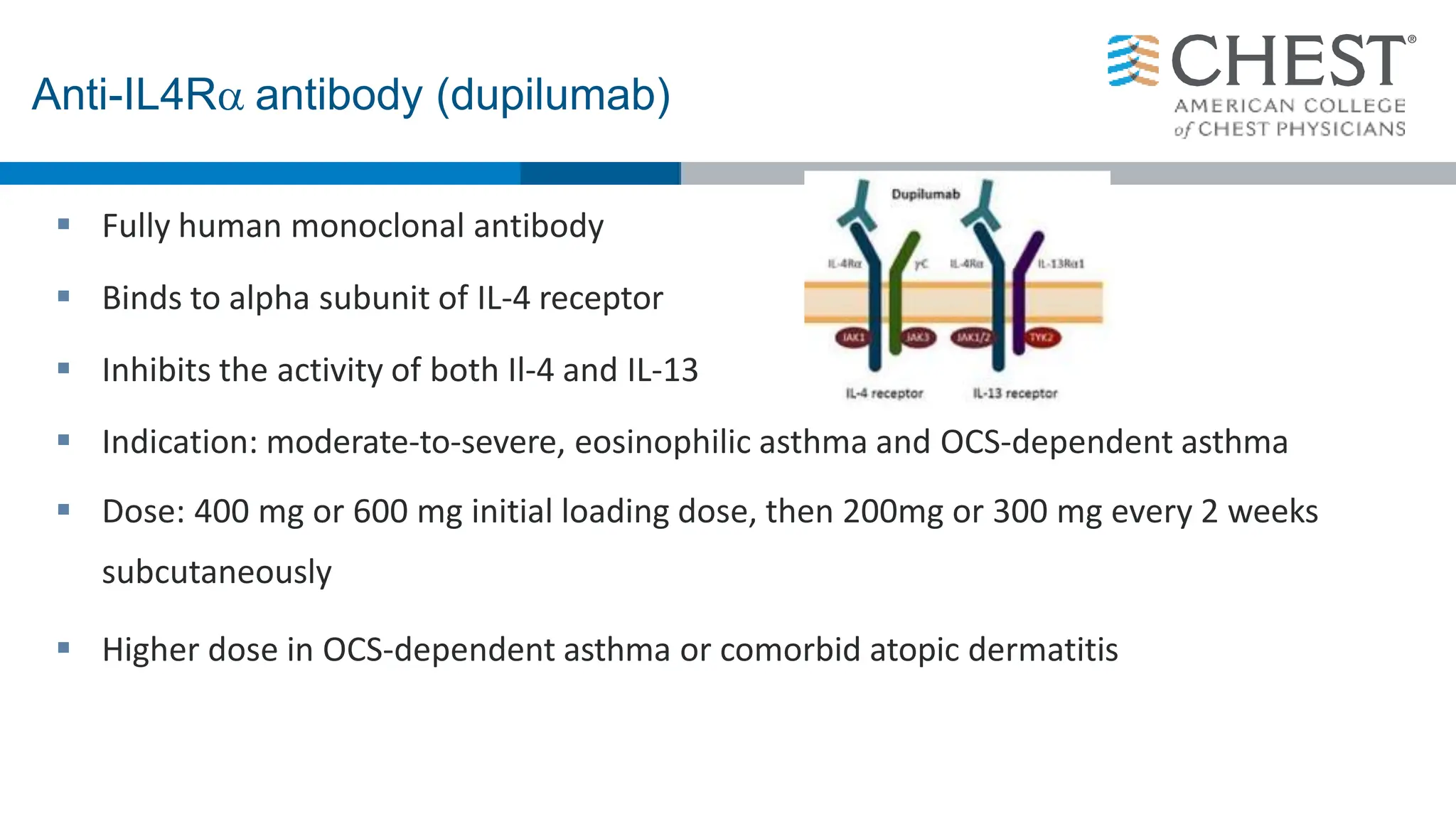

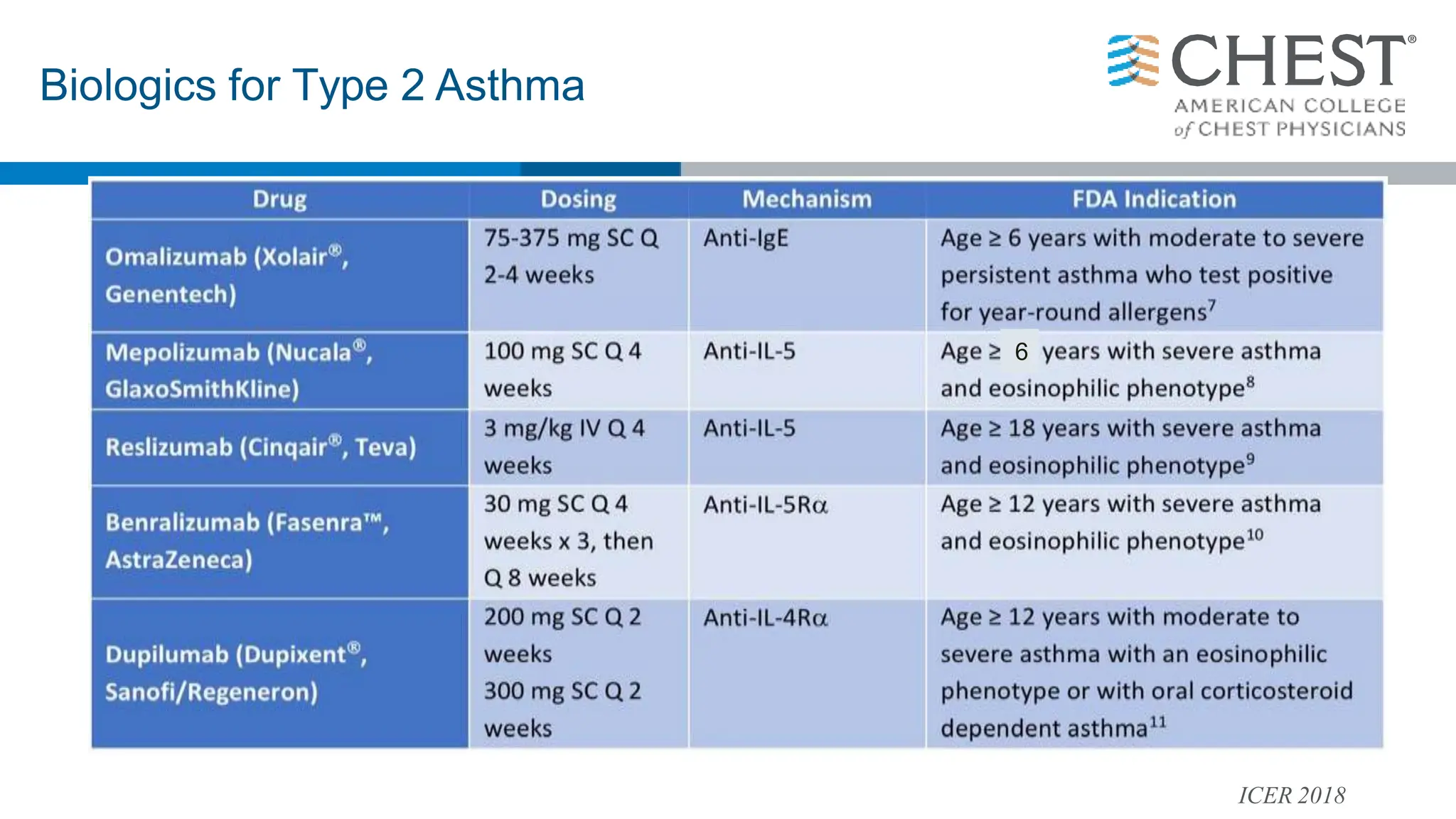

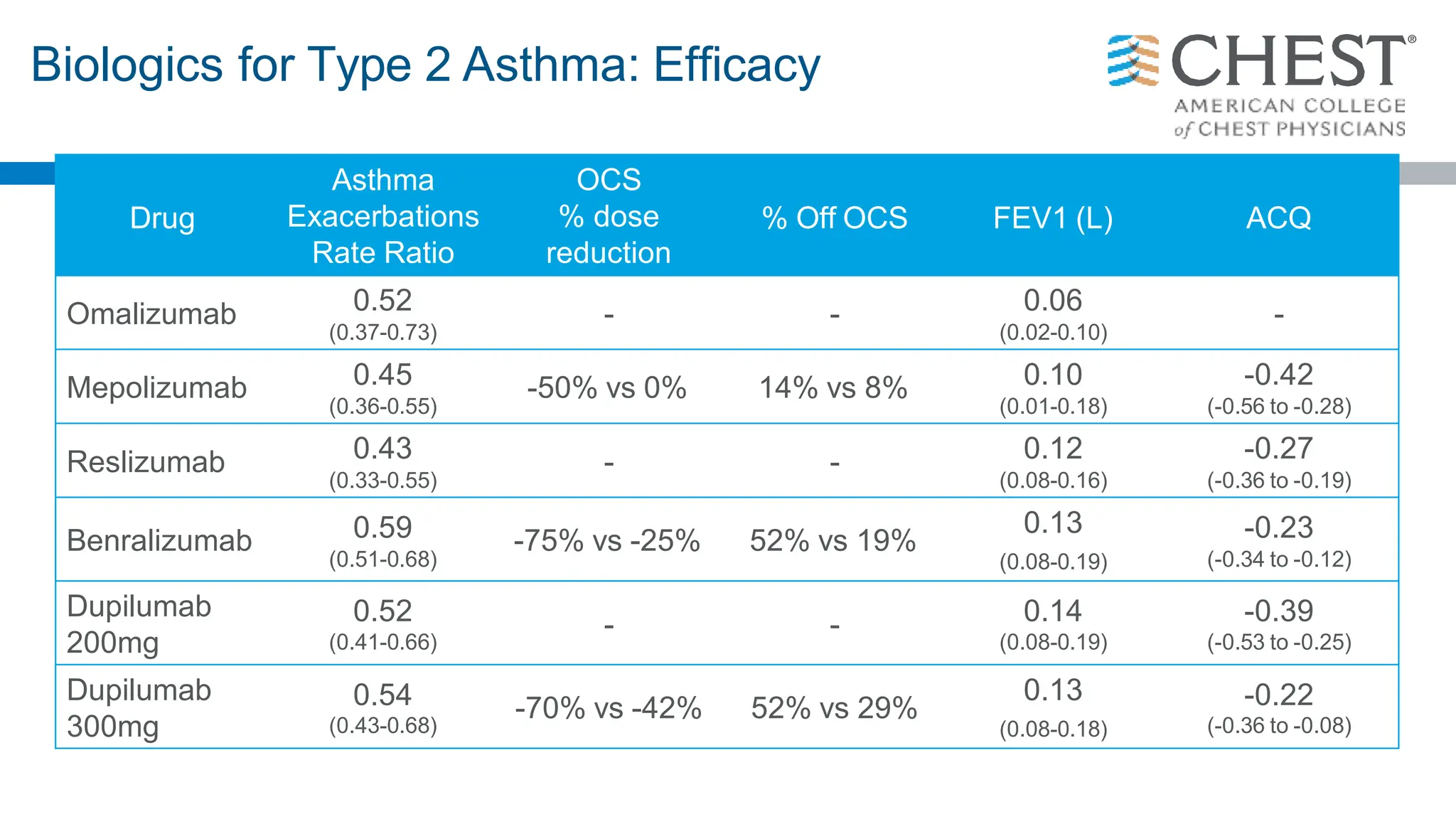

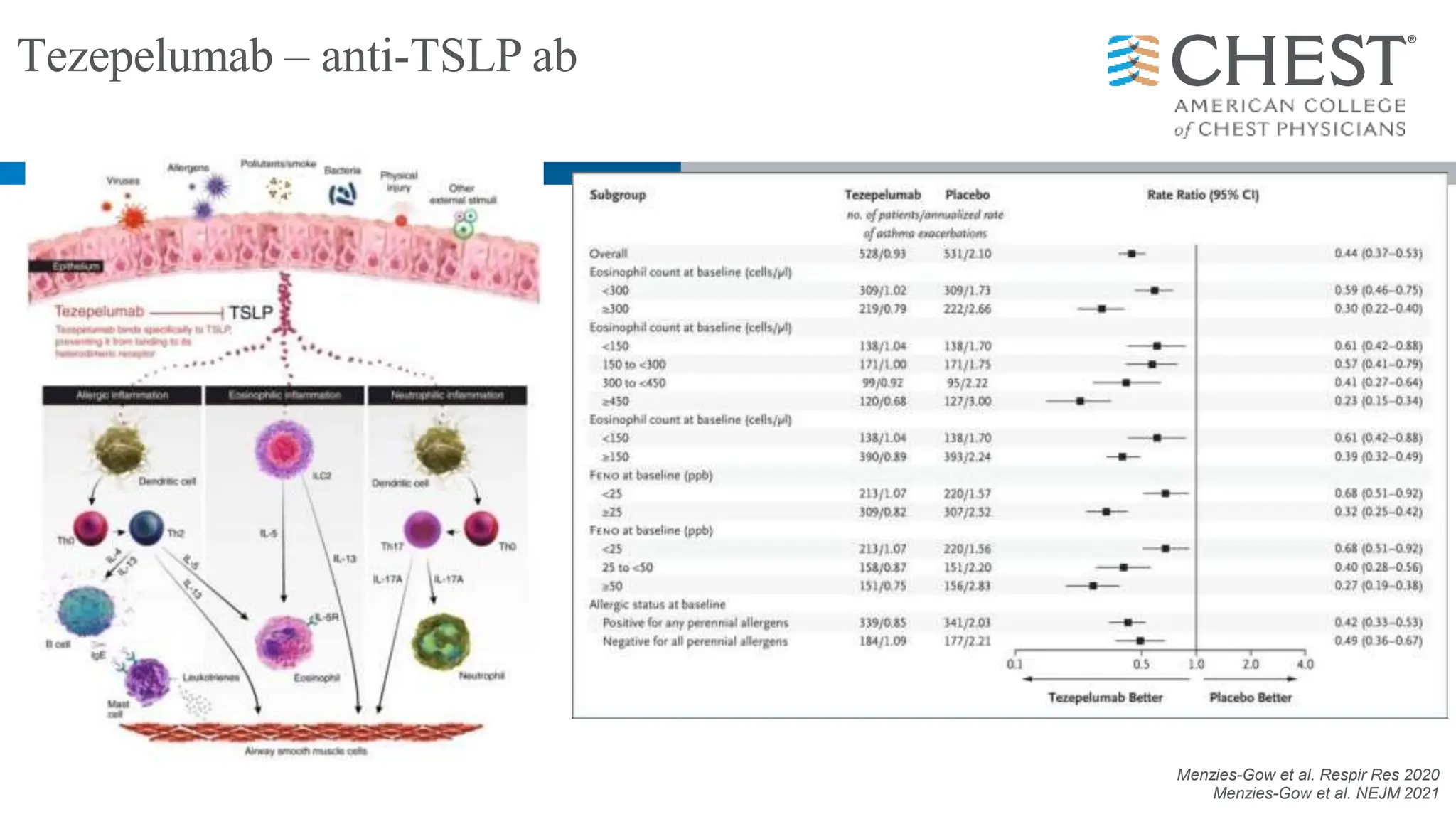

- Type 2 inflammation, involving cytokines like IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, underlies many asthma phenotypes and is a target of new biologic therapies.