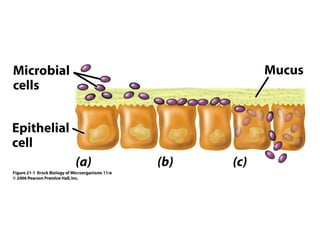

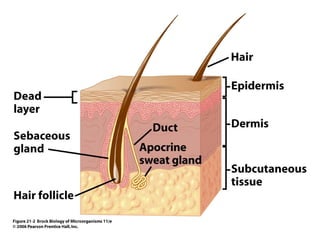

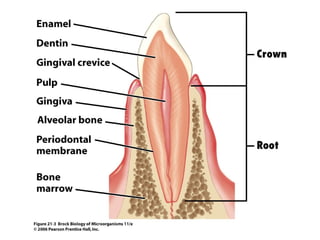

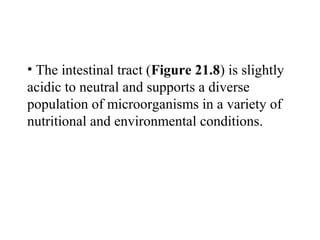

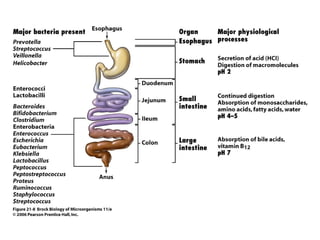

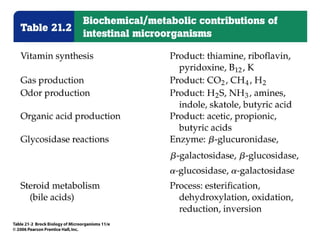

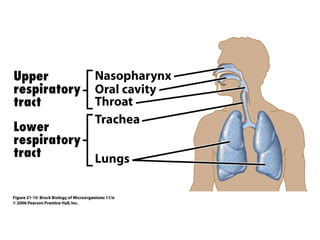

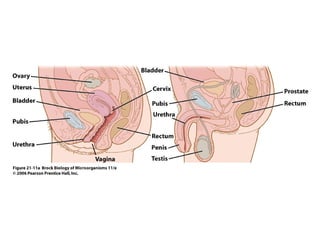

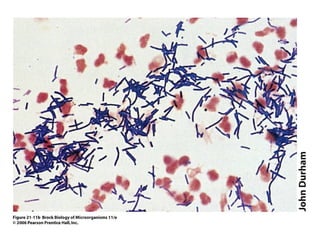

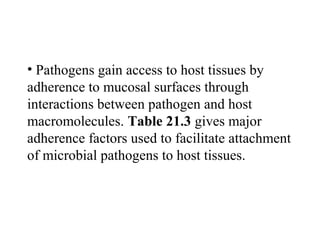

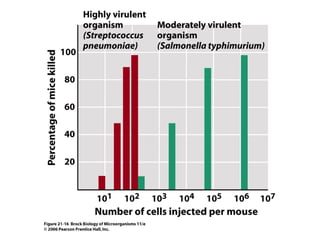

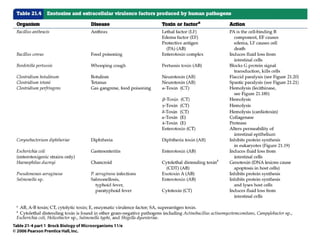

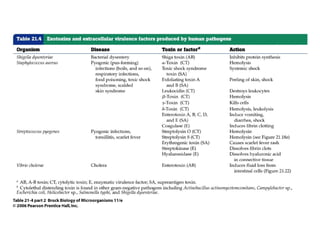

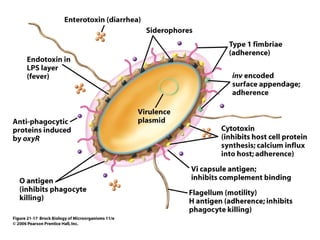

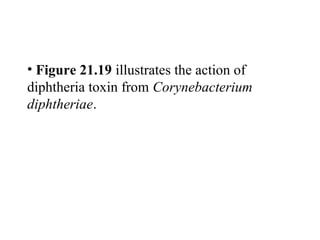

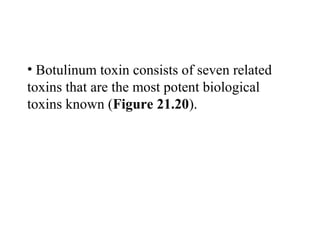

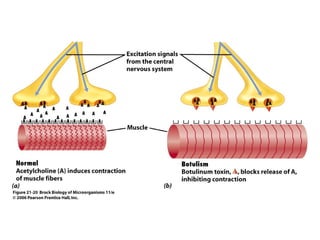

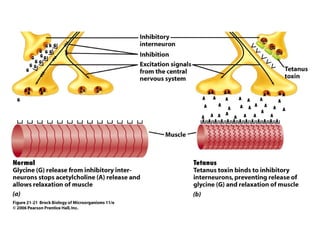

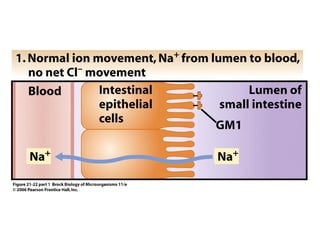

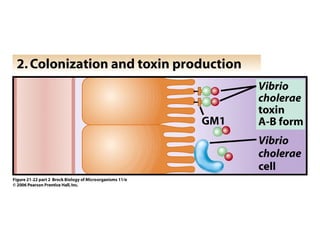

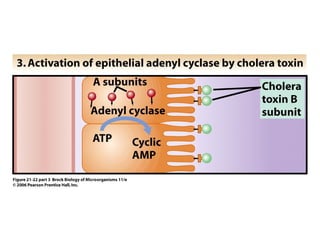

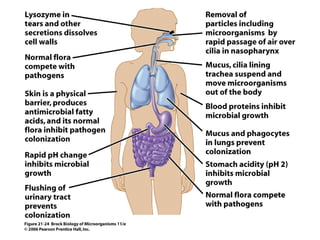

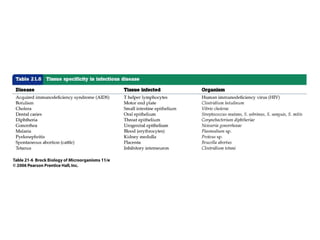

This document summarizes a chapter from a biology textbook about microbial interactions with humans. It covers both beneficial microbes that normally inhabit the body and potential pathogens. For beneficial microbes, it describes the normal flora of the skin, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and other body areas. It then discusses how pathogens can potentially cause harm by entering the host, colonizing tissues, and using virulence factors like toxins. Lastly, it covers host defenses against infection and factors that increase infection risk.