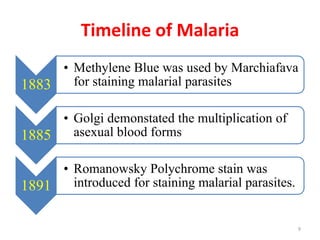

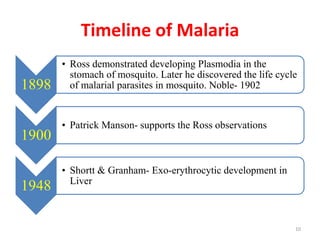

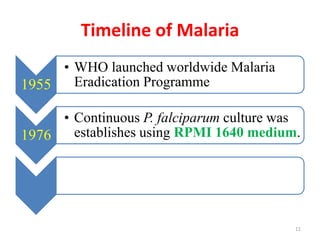

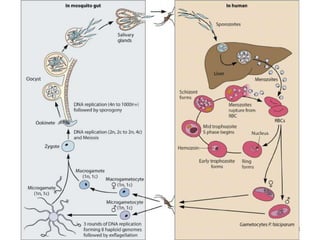

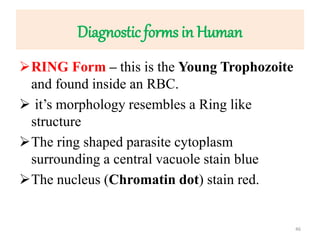

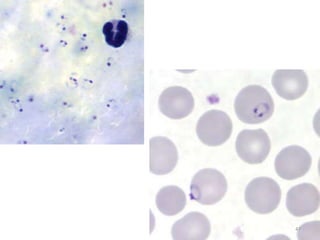

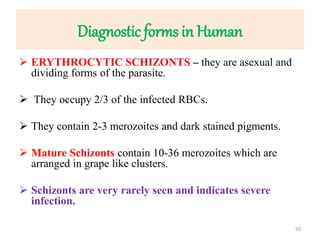

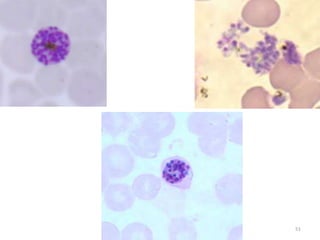

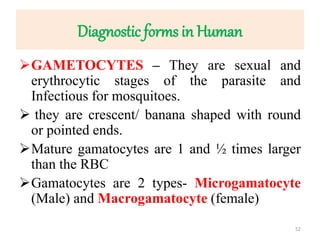

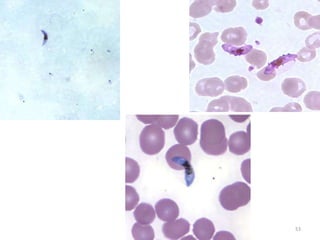

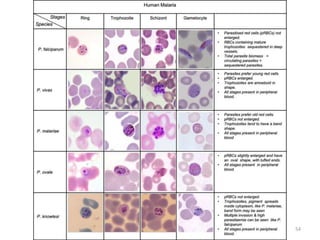

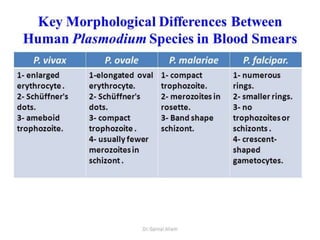

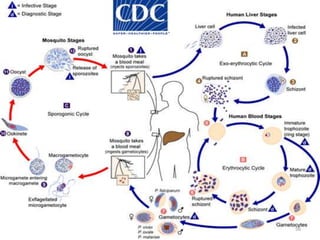

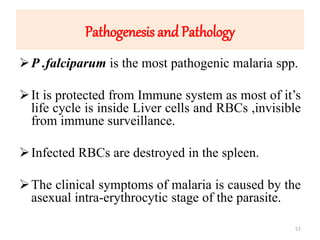

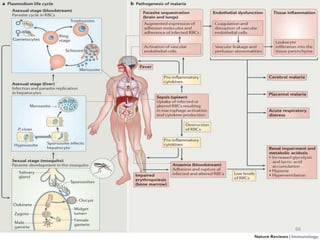

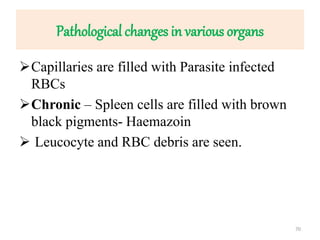

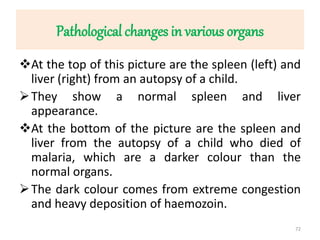

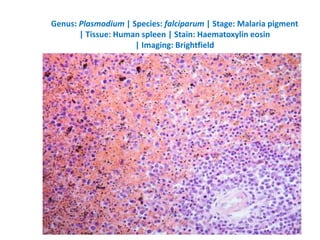

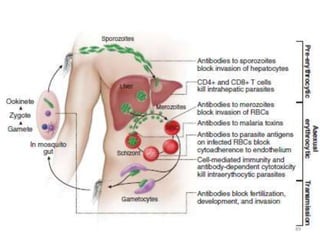

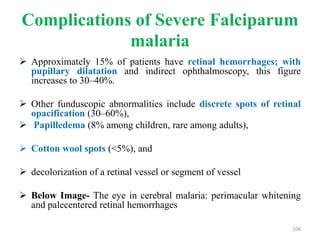

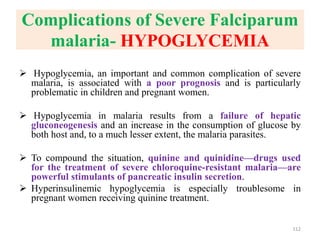

The document provides a detailed overview of malarial parasites, focusing on the genus Plasmodium, particularly P. falciparum. It includes descriptions of the life cycle, gametocytogenesis, clinical symptoms, pathogenesis, and the historical timeline of malaria research and treatment. The document emphasizes the pathogenicity of P. falciparum, its virulence mechanisms, and the pathological changes it induces in various organs.

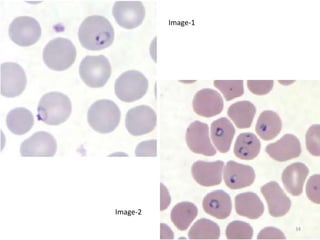

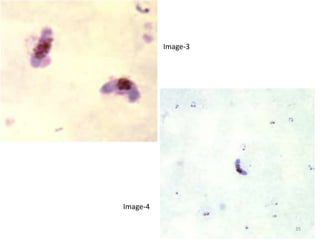

![Plasmodium falciparum-LIFE CYCLE

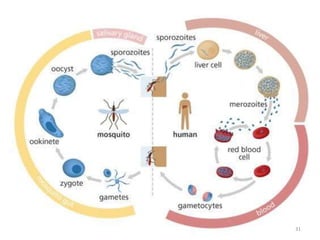

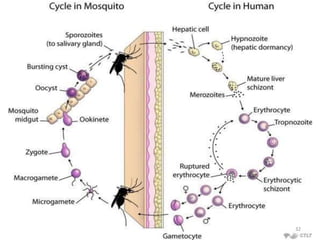

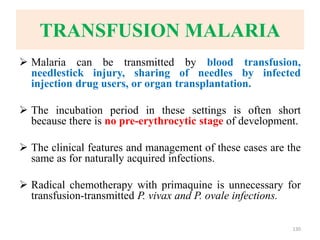

Human cycle begins with a bite of Infected

Female Anopheles mosquito/ Transfusion of

Infected blood

(Except-> Transfusion malaria and Congenital

malaria)

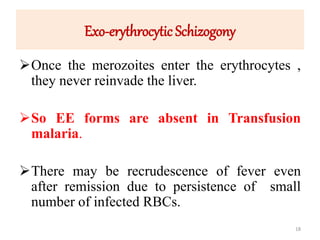

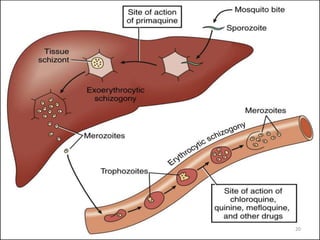

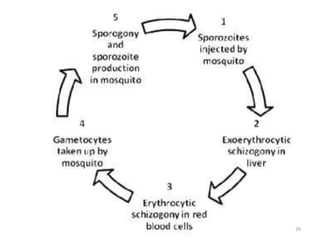

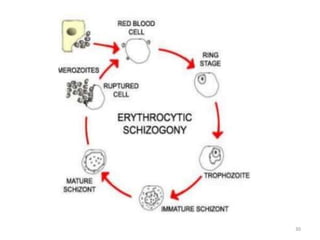

There are 2 stages in the Human cycle

1] Exo-erythrocytic (EE) schizogony in the Liver

2] Erythrocytic schizogony in the RBCs.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-14-320.jpg)

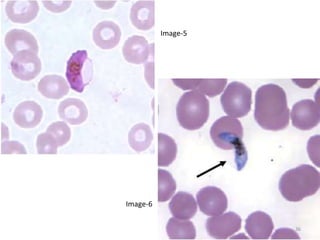

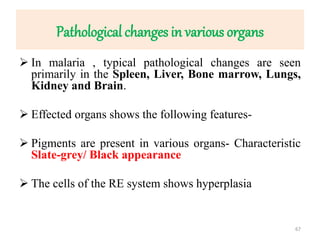

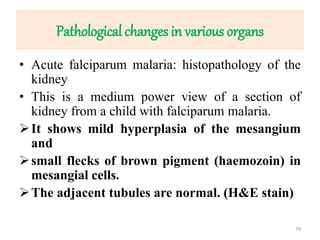

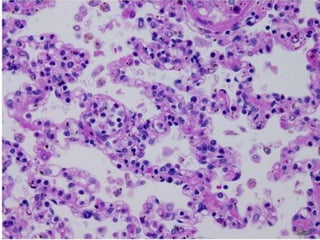

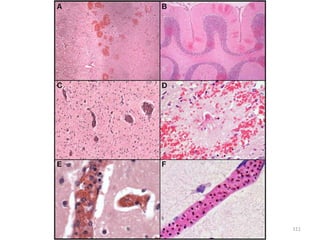

![Pathological changes in various organs

Histopathology of the lung in a fatal case of adult

falciparum malaria

There is expansion of alveolar capillaries by

sequestered parasitized erythrocytes and host

inflammatory leukocytes.

Monocytes and neutrophils within alveolar septal

capillaries contain phagocytosed hemozoin

pigment

(hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining,

magnification 3 400,

84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-84-320.jpg)

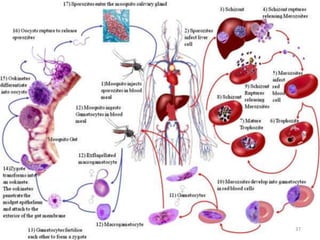

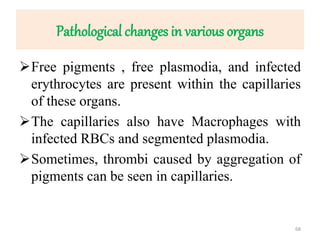

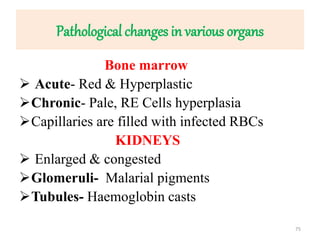

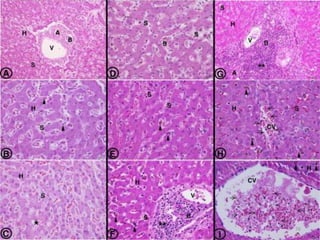

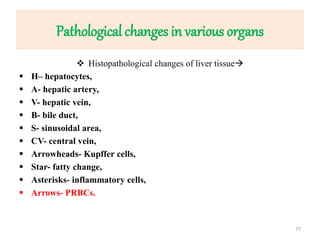

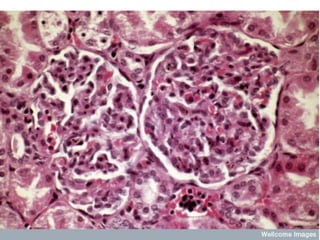

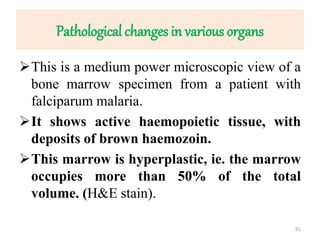

![Pathological changes in various organs

HEAMATOLOGICAL CHANGES

Anemia-

1] Enormous destruction of both Parasitised and non-

parasitised RBCs- Antigenically different Parasitised

RBCs bind with the non-parasitised and form Rossets and

block vanules.

Non parasitised RBCs are destroyed probably by auto-

immune mechanism.

2] Decreased erythropoesis in Bone marrow- This is in

part due to TNF Toxicity. In long term infection there may

be Leucopenia & decreased Hb levels

85](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-85-320.jpg)

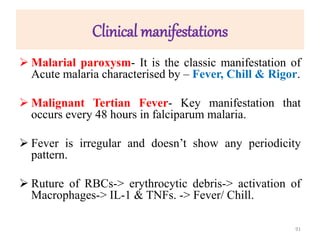

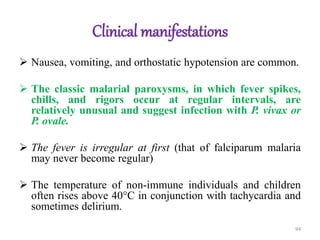

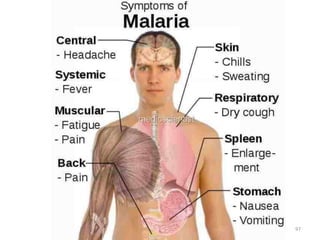

![Clinical manifestations

The clinical symptoms can be divided into –

A] Prodromal period

B] Malarial paroxysm

C] Anemia

D] Hepatospleenomegaly.

Prodromal period- Malarial paroxysm is preceded by a Prodromal

period which varies from a few to several days.

Non-specific symptoms such as

Malaise,

Myalgia,

Headache, and Fatigue are seen.

Local symptoms like Chest pain, Abdominal pain and Arthralgia

are also found.

90](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-90-320.jpg)

![Recurrence of Clinical malaria

Recurrence of clinical malaria after treatment may occur

due to 3 reasons-

1] True relapse: It is caused by Hypnozoites in P. vivax & P.

ovale.

It is due to re-emrgence of blood stage parasites from latent

parasites(Hypnozoites) in liver.

Since no Hypnozoites in P. falciparum No true relapse.

2] Recrudescence- It is seen falciparum malaria d/t

inadequate t/t and seen in – Drug resistance, Immuno-

suppression & pregnancy.

132](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-132-320.jpg)

![Recurrence of Clinical malaria

3] Latent malaria- This condition refers to a

state of asymptomatic malaria harbouring

plasmodia gametocytes in the peripheral blood.

These persons are infectious to mosquitoes and

act as Reservoirs .

133](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/malaria-210531105144/85/Malaria-133-320.jpg)