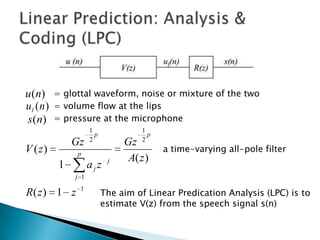

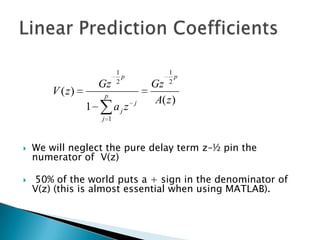

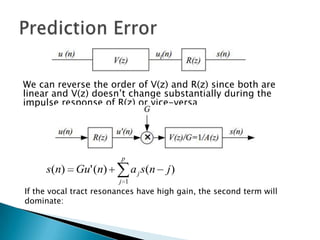

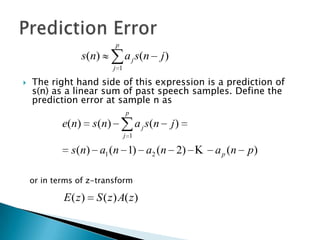

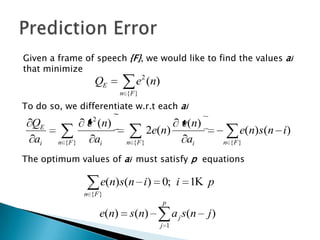

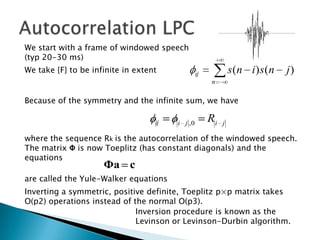

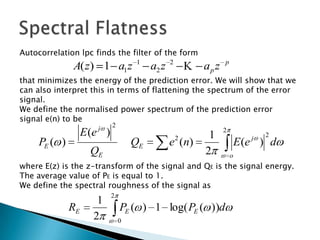

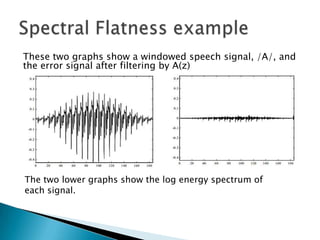

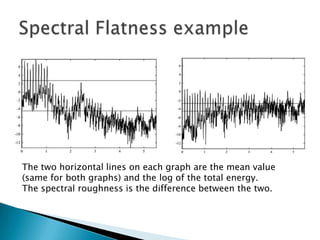

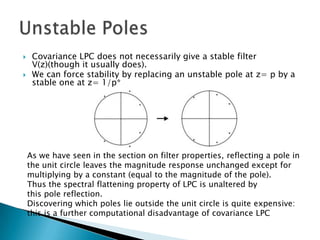

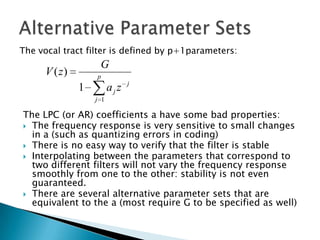

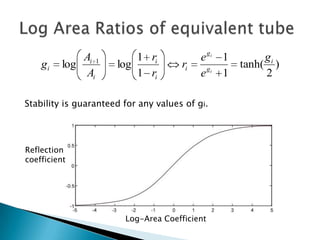

This document discusses linear prediction analysis (LPC) for speech recognition. It begins by deriving the linear prediction equations and describing the autocorrelation method of LPC. It then interprets the LPC filter as a spectral whitener that flattens the spectrum of the prediction error. The document discusses alternative methods like covariance LPC and closed phase covariance LPC. It also describes alternative parameter sets that can represent the LPC filter, such as pole positions, reflection coefficients, and log area ratios.