The document discusses different methods for fitting equations to data, including interpolating polynomials, least squares fitting, and examples of non-polynomial forms. It provides sample MATLAB code for finding an interpolating polynomial that passes through every data point in a sample data set, as well as code for performing a cubic least squares fit. The document concludes by giving practice problems involving fitting equations to saturation property data for water.

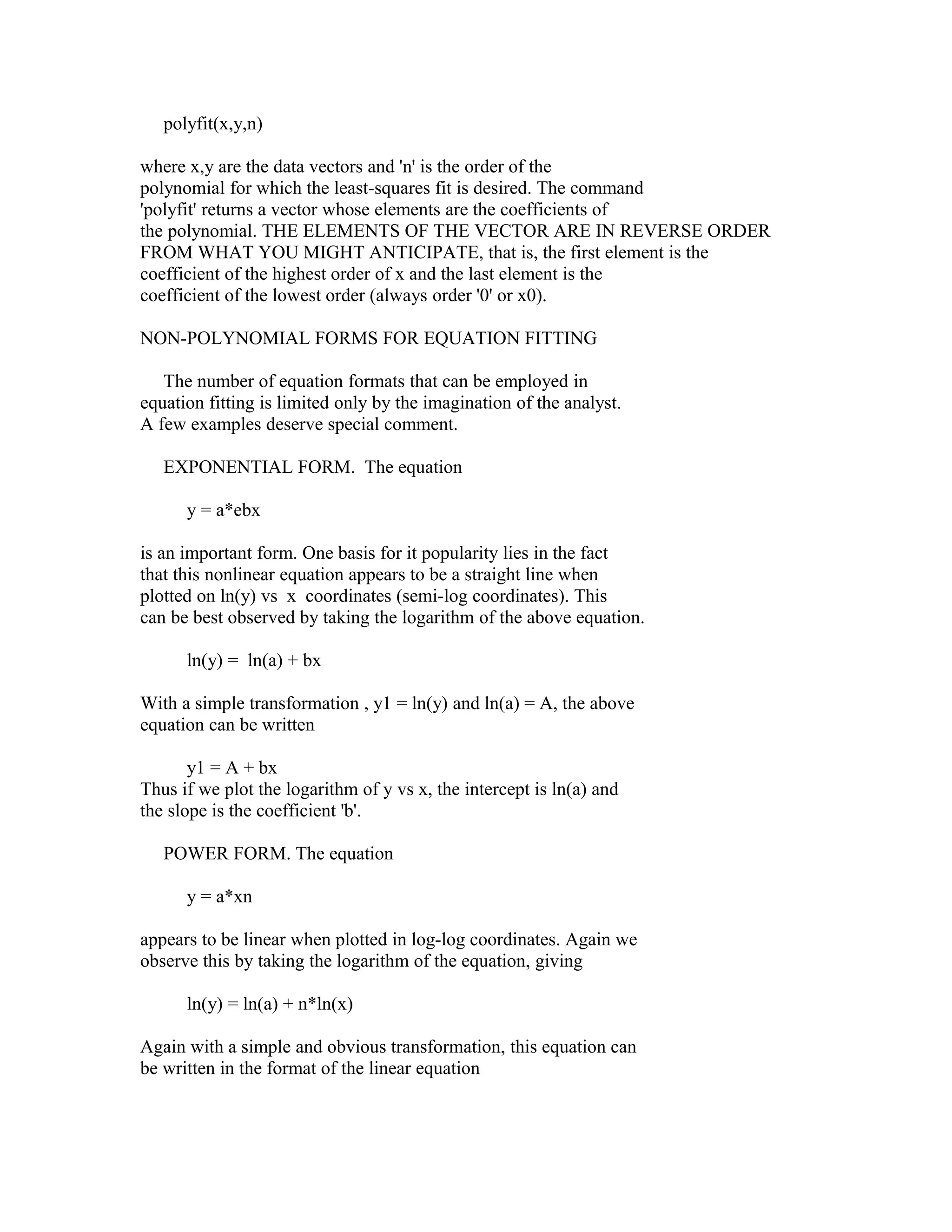

![This is a solvable set of 'n+1' equations with 'n+1' unknowns. The

unknowns are the coefficients a0, a1,......an. If there exists only

two or three equations, the solution procedure for the unknown

coefficients can conveniently follow Cramer's Rule. In general,

however, it is common to rely on matrix algebra to manipulate these

equations into a format for which n operations of back substitution

will obtain the unknown coefficients. Here we will simply rely on

the methods of right (or left) division in 'matlab' to obtain the

unknown coefficients, leaving the details of the numerical method

for back substitution for later discussion.

Note that the set of equations can be conveniently expressed

by the matrix equation

[y] = [X][a]

where

y1

1

x1 x12.....x1n+1

y2

1

[y] =

[X] =

y3

1

.

. .

.

. .

.

. .

yn+1

1

a1

x2 x22.....x2n+1

a2

[a] =

x3 x32.....x3n+1

a3

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

xn+1 xn+12... xn+1n+1

an+1

Note that the right side of the matrix equation must be the product

of a 'n+1' x 'n+1' square matrix times a 'n+1' x 1 column matrix!

The solution using Gauss elimination calls for left division in

'matlab' or

[a] = [X][y]

Using this method, we can find the coefficients for a n-degree

polynomial that passes exactly through 'n+1' data points.

If we have a large data set, each data pair including some

experimental error, the n-degree polynomial is NOT A GOOD CHOICE.

Polynomials of degree larger than five or six often have terribly

unrealistic behavior BETWEEN the data points even though the

polynomial curve passes through every data point ! As an example,

consider these data.

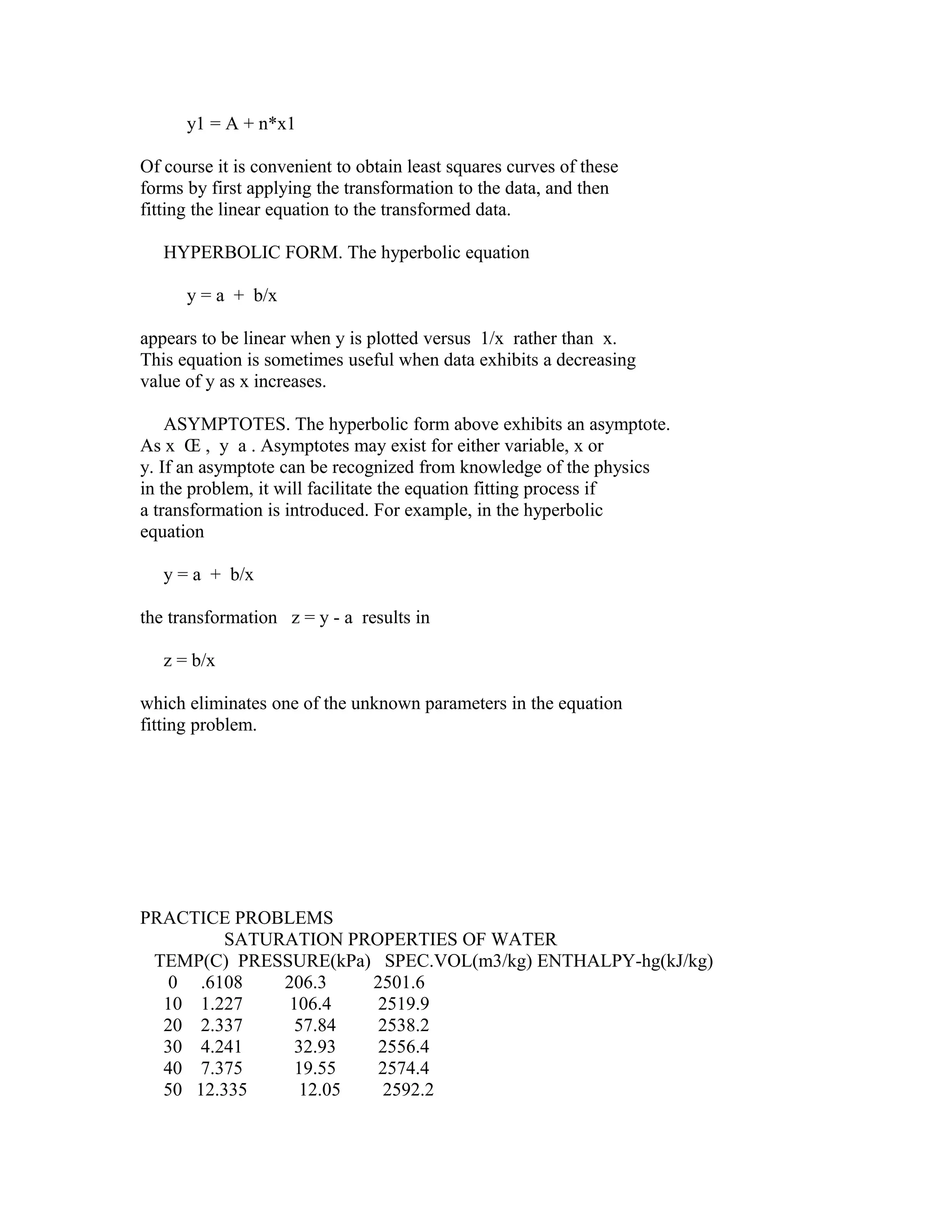

x

y](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson8-140121212815-phpapp02/75/Lesson-8-2-2048.jpg)

![2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

4

3

5

4

7

5

7

10

9

There are 9 data points in this set. It is clear that as x

increases, so also does y increase; however, it appears to be doing

so in a nonlinear way. Let's see what the data looks like. In

'matlab', create two vectors for these data.

x9 = [2:1:10];

y9 = [ 4 3 5 4 7 5 7 10 9 ];

To observe these data plotted as points, execute

plot(x9,y9,'o')

Because we have nine data pairs, it is possible to construct an

eighth-degree interpolating polynomial.

y = a0 + a1x + a2x2 + a3x3 + ....... + a8x8

To find the unknown coefficients, define the column vector y

y = y9'

and the matrix X

X = [ones(1,9);x9;x9.^2;x9.^3;x9.^4;x9.^5;x9.^6;x9.^7;x9.^8]'

Note that X is defined using the transpose, the ones() function and

the array operator ' .^ '. With X and y so defined, they satisfy

the equation

[X][a] = [y]

Solve for the coefficients, matrix a in the above equation, by

entering the command](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson8-140121212815-phpapp02/75/Lesson-8-3-2048.jpg)

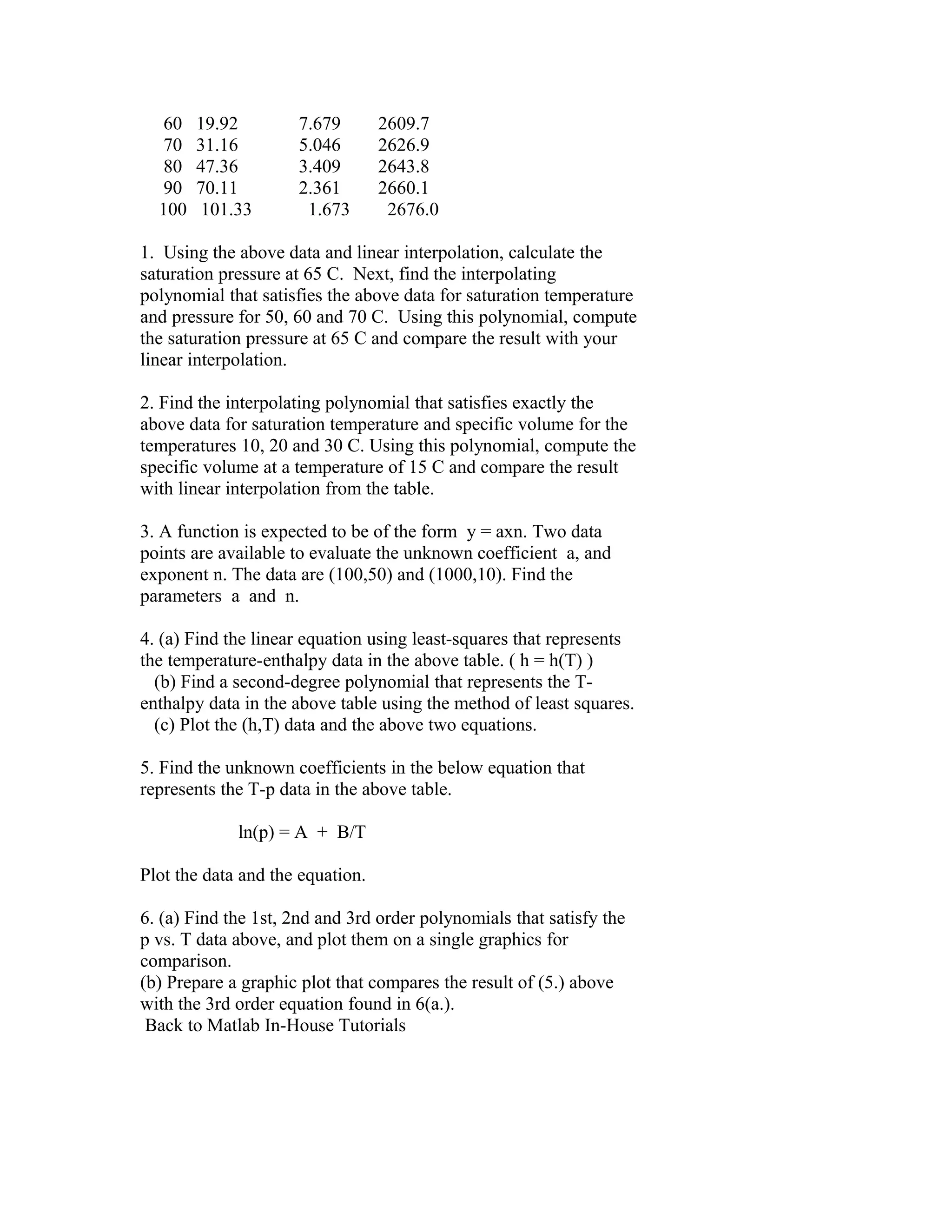

![a = Xy

which results in

a = [ 1.0e+003*

3.8140

-6.6204

4.7831

-1.8859

.4457

- .0649

.0057

- .0003

.0000 ]

Note that the ninth coefficient a(8) appears to be zero. Actually,

it is finite, it only appears to be zero because 'matlab' is

printing only 4 significant figures to the left of the decimal

point. To observe the coefficients with more significant figures,

enter the commands

format long

a

and the format is changed to one with 15 significant digits.

Clearly a(8) is not zero, it is a small number because it is

multiplying a number, x, raised to the eight power.

Now that we have the coefficients, let's generate a

sufficient number of points to create a smooth curve. For x, form

a vector over the range 2 <= x <= 10 in increments of 0.1.

x = [ 2:.1:10 ];

For y, calculate the value of the eighth degree polynomial for each

x.

y =a(1)+ a(2).*x + a(3).*x.^2 + a(4).*x.^3 + a(5).*x.^4...

+ a(6).*x.^5 + a(7).*x.^6 + a(8).*x.^7 + a(9).*x.^8;

Now plot (x,y) and the data points (x9,y9).

plot(x,y,x9,y9,'o')

The polynomial results appear to pass exactly through every data

point, but clearly the polynomial is useless for representing our](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson8-140121212815-phpapp02/75/Lesson-8-4-2048.jpg)

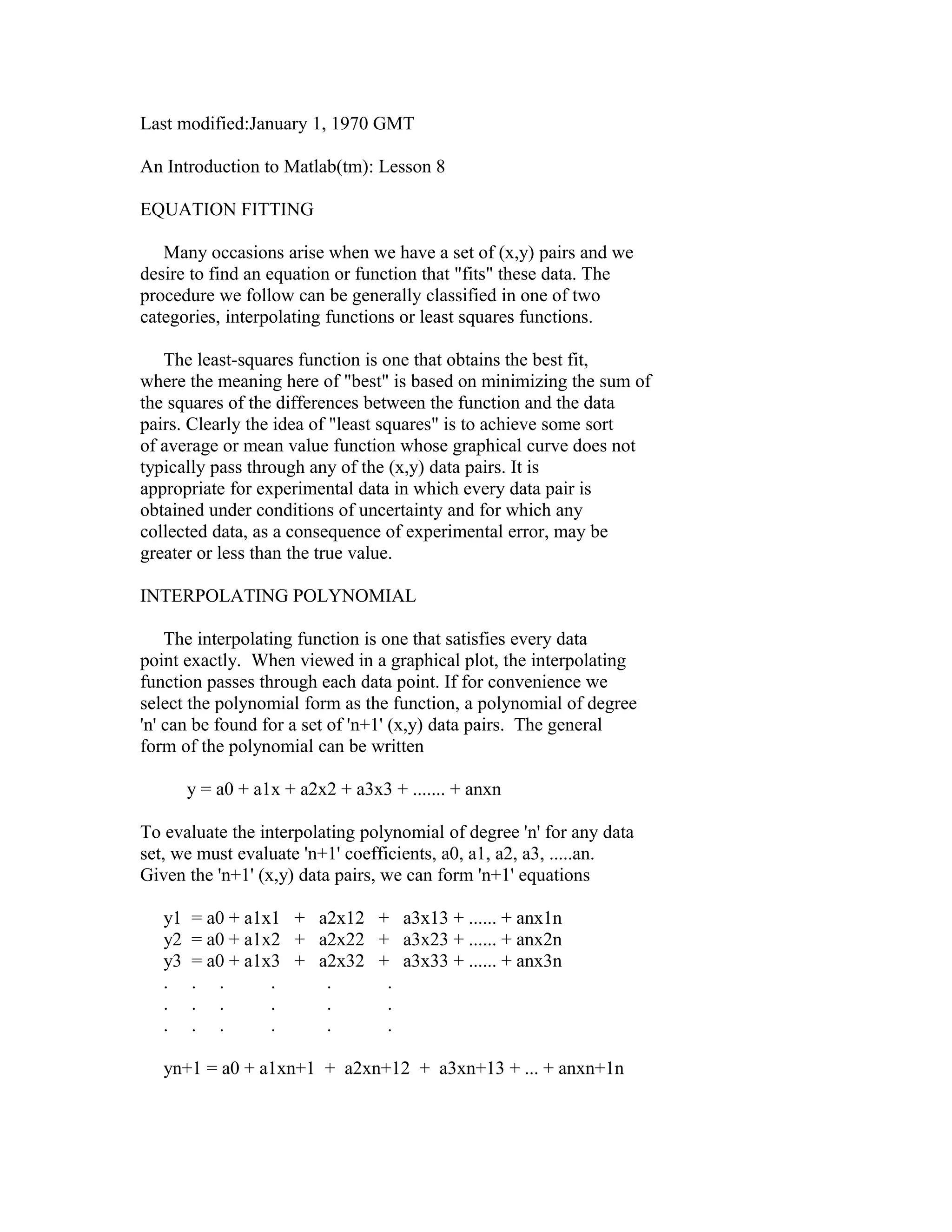

![impression of the data at any other point within the range of x!

This is a common behavior for high-order interpolating polynomials.

For this reason, one should never attempt to use high order

interpolating polynomials to represent experimental data.

LEAST SQUARES

A lower order polynomial, possibly a cubic polynomial might be

a sufficient choice; however, a cubic polynomial would have 4

unknown coefficients and we have 9 data points. Which four of the

nine do we select? The method of least squares responds to this

problem by taking an "average" or best curve that includes

information from every one of the data points. The method is well

explained in Chapter 3 of the text, EXPERIMENTAL METHODS FOR

ENGINEERS by J. P. Holman. The details will not be repeated here;

however, the text specializes the result to a first and second

order polynomials. Here we would like to retain the polynomial

format and express the result for the third degree polynomial. If

we desire a quadratic or linear equation, it is easy to select the

reduced matrices that create the desired coefficients. Thus we

find that for the equation

y = a0 + a1x + a2x2 + a3x3

the four unknown coefficients are evaluated from

a=XB

where

a0

m ‘xi ‘xi2 ‘xi3

‘yi

a1

‘xi ‘xi2 ‘xi3 ‘xi4

‘xiyi

[a] =

[X] =

[B] =

a2

‘xi2 ‘xi3 ‘xi4 ‘xi5

‘xi2yi

a3

‘xi3 ‘xi4 ‘xi5 ‘xi6

‘xi3yi

The summation is over the range 1 to m, where m is the number of

(x,y) data pairs. Note that for any least-squares equation fit,

you must have at least one more data point than unknown

coefficients, or m > n+1.

MATLAB FUNCTION FOR LEAST SQUARES

There is a convenient function in 'matlab' for polynomial

equation fitting with the method of least squares. The command is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson8-140121212815-phpapp02/75/Lesson-8-5-2048.jpg)