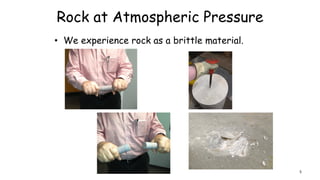

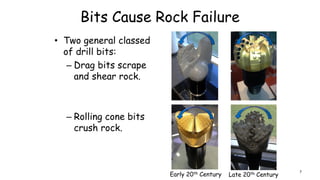

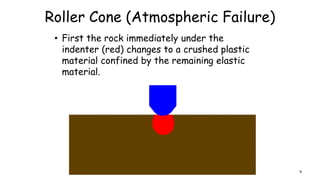

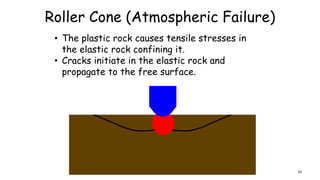

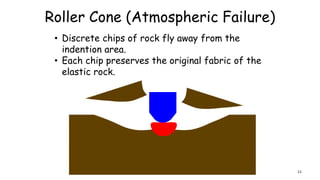

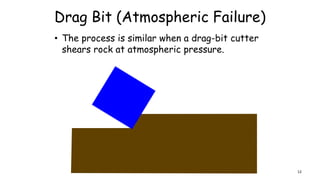

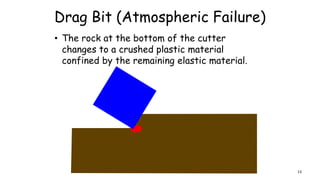

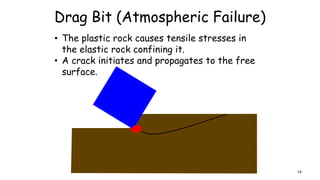

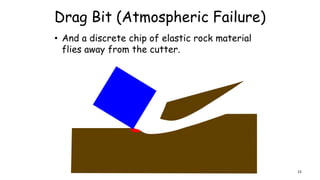

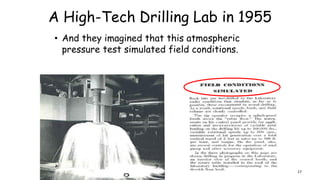

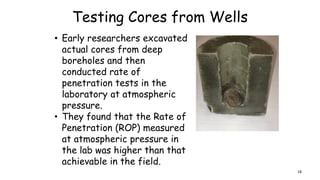

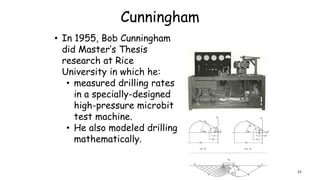

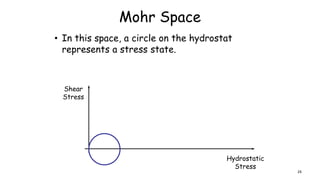

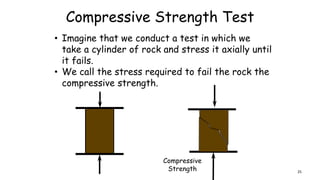

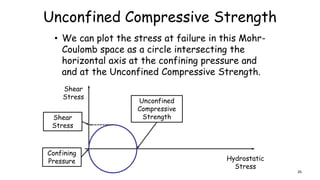

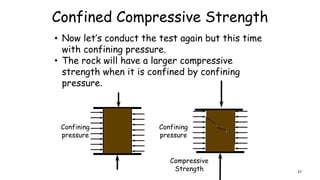

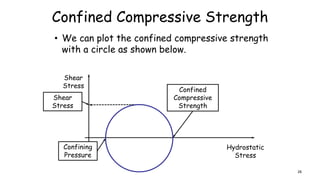

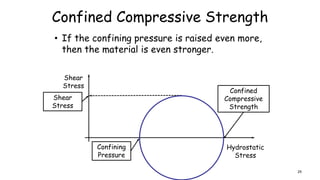

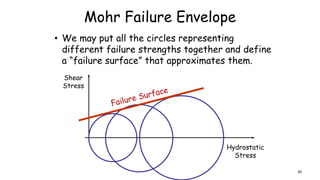

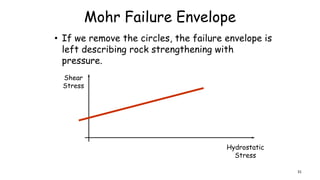

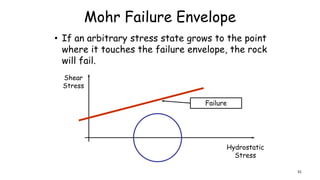

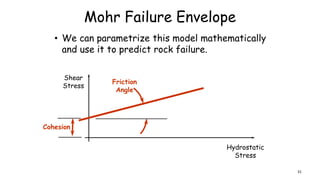

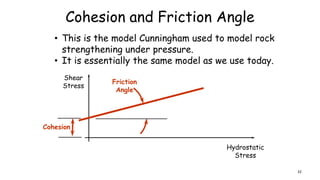

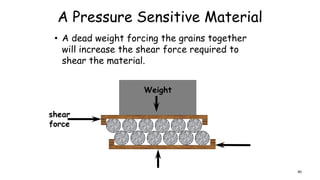

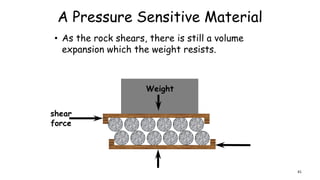

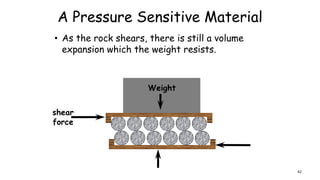

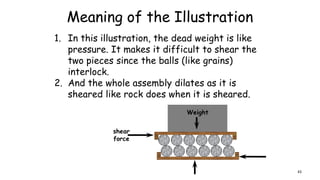

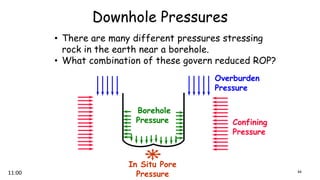

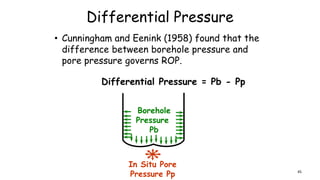

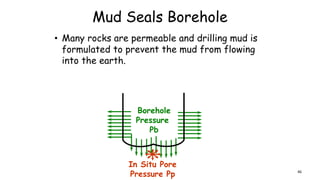

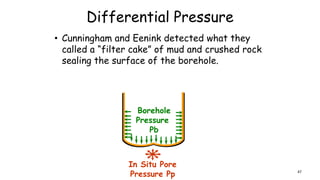

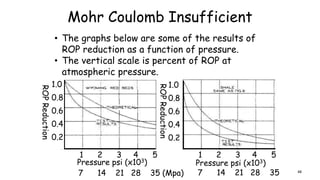

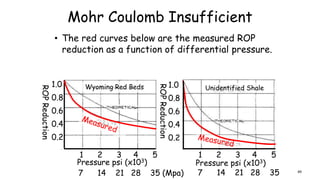

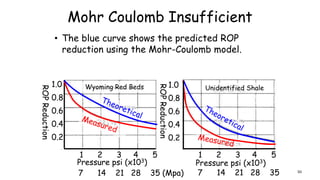

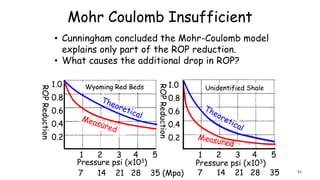

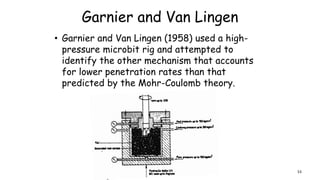

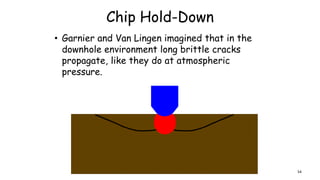

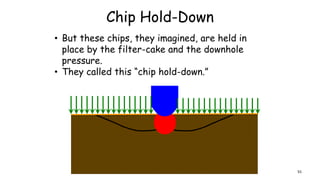

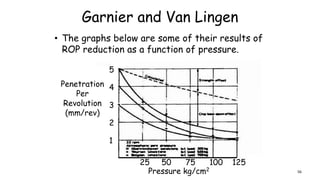

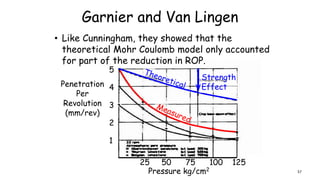

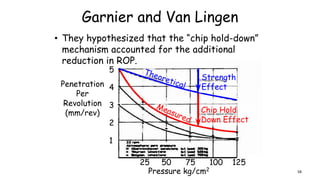

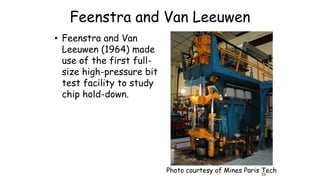

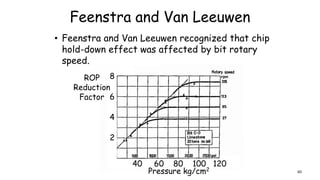

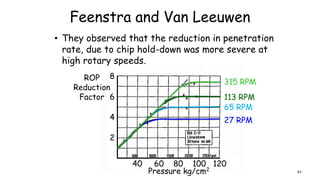

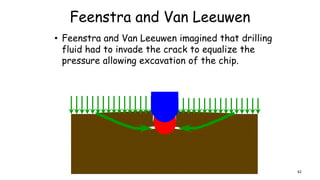

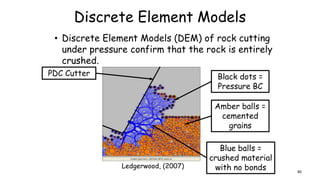

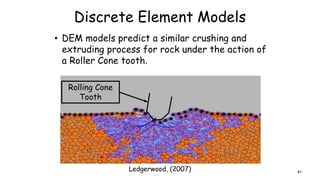

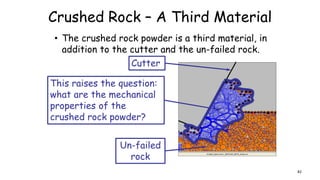

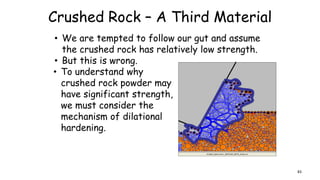

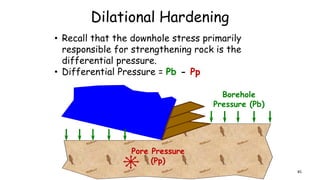

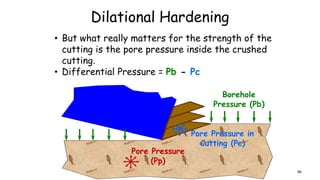

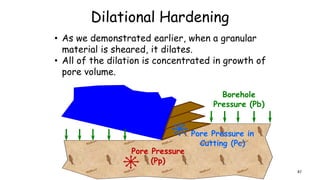

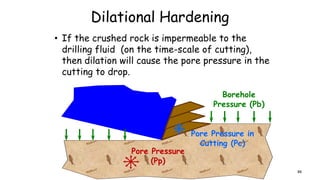

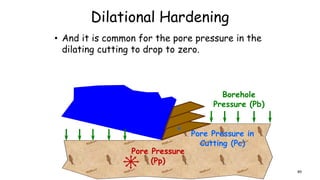

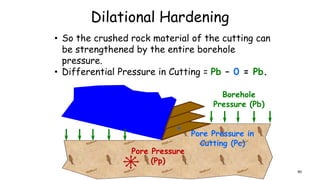

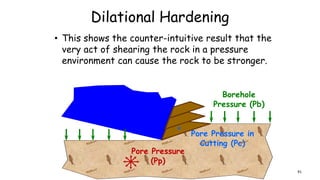

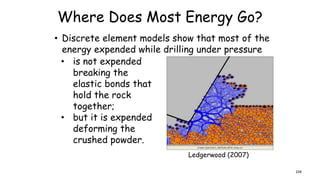

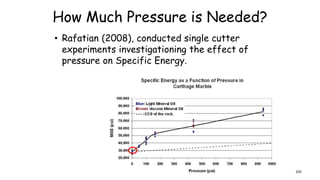

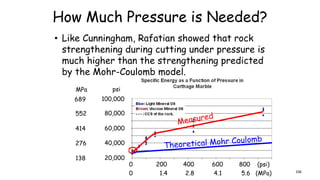

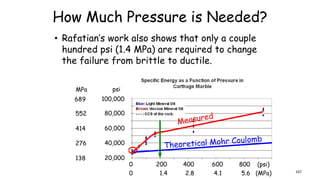

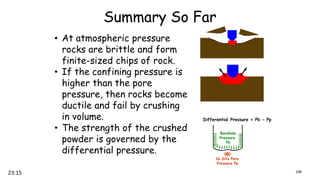

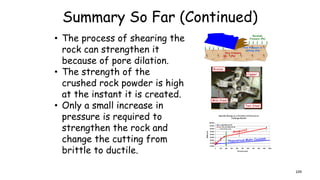

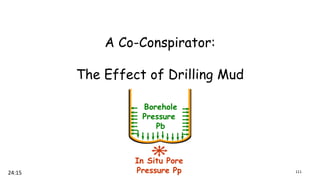

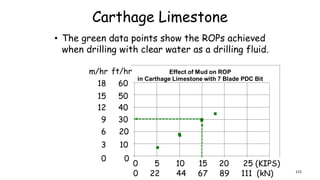

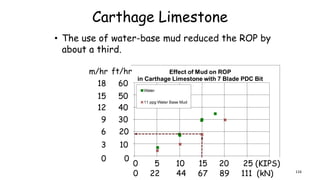

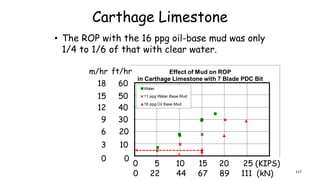

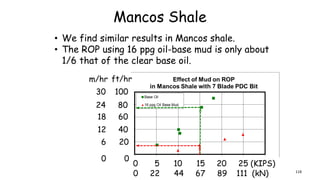

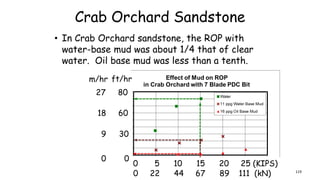

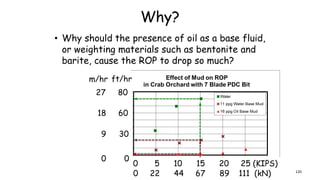

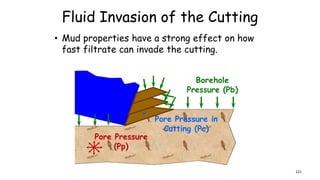

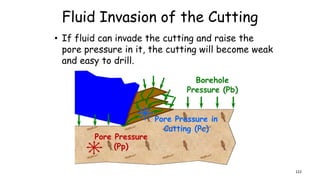

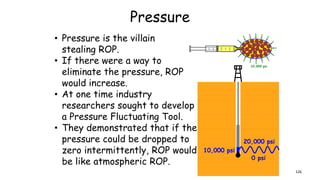

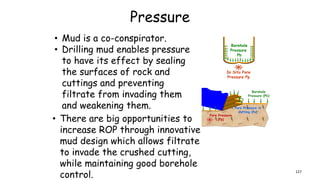

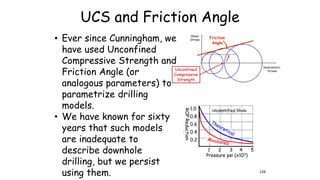

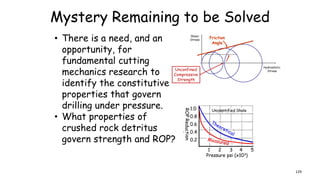

This document summarizes a presentation on solving the mystery of low rates of penetration in deep wells. It discusses how early researchers thought rock failure at atmospheric pressure simulated downhole conditions, but testing found lower ROPs downhole. The Mohr-Coulomb model was the first suspect considered to explain rock strengthening with pressure, but was found to only explain part of the reduction in ROP observed. Additional factors beyond simple rock failure criteria were discovered to influence ROP at depth.