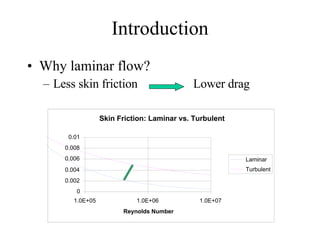

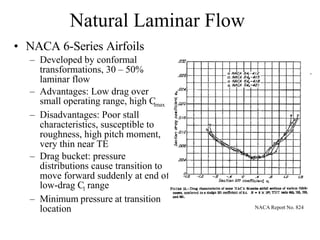

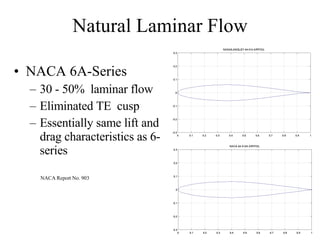

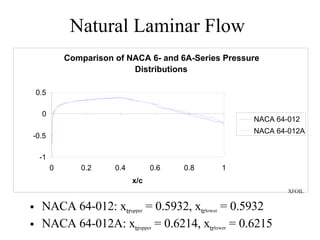

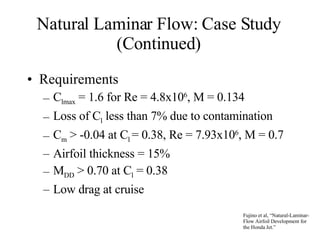

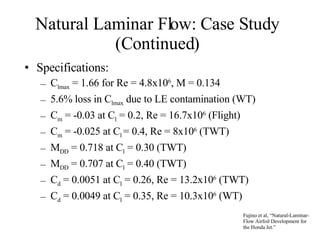

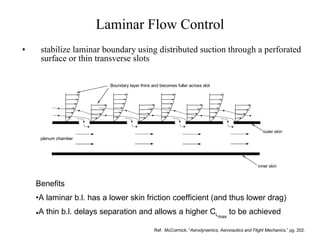

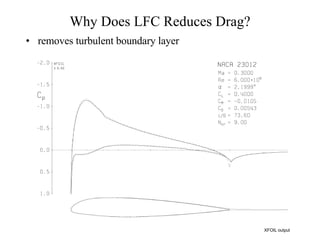

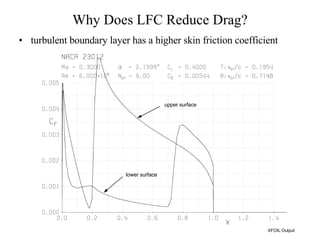

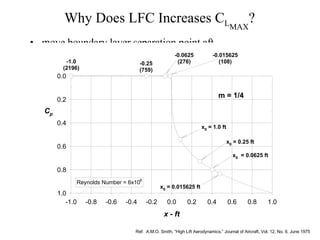

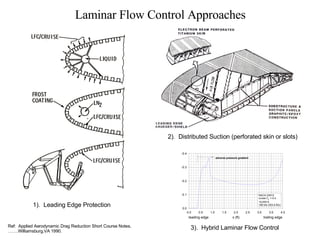

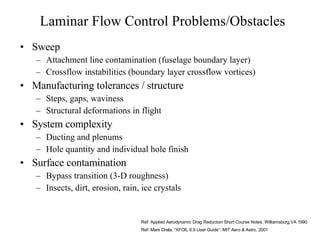

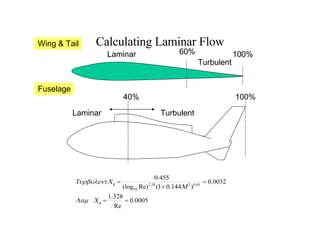

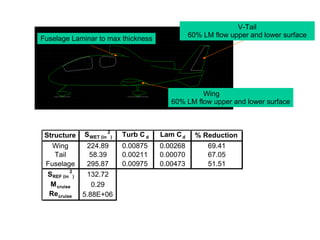

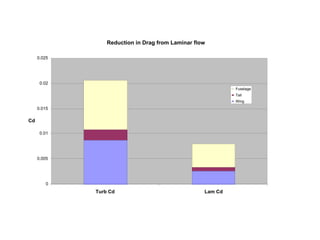

The document discusses laminar flow and its advantages for reducing drag on airfoils and aircraft. It provides details on natural laminar flow airfoils and the NACA 6-series airfoils which can achieve 30-50% laminar flow. The document also describes laminar flow control techniques like suction and discusses challenges like surface contamination and manufacturing tolerances. It summarizes a case study of the SHM-1 airfoil developed for the Honda Jet using inverse design methods to maximize laminar flow.